Monomial Factorization of Symplectic Maps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Review of Some Basic Mathematical Concepts and Differential Calculus

A Review of Some Basic Mathematical Concepts and Differential Calculus Kevin Quinn Assistant Professor Department of Political Science and The Center for Statistics and the Social Sciences Box 354320, Padelford Hall University of Washington Seattle, WA 98195-4320 October 11, 2002 1 Introduction These notes are written to give students in CSSS/SOC/STAT 536 a quick review of some of the basic mathematical concepts they will come across during this course. These notes are not meant to be comprehensive but rather to be a succinct treatment of some of the key ideas. The notes draw heavily from Apostol (1967) and Simon and Blume (1994). Students looking for a more detailed presentation are advised to see either of these sources. 2 Preliminaries 2.1 Notation 1 1 R or equivalently R denotes the real number line. R is sometimes referred to as 1-dimensional 2 Euclidean space. 2-dimensional Euclidean space is represented by R , 3-dimensional space is rep- 3 k resented by R , and more generally, k-dimensional Euclidean space is represented by R . 1 1 Suppose a ∈ R and b ∈ R with a < b. 1 A closed interval [a, b] is the subset of R whose elements are greater than or equal to a and less than or equal to b. 1 An open interval (a, b) is the subset of R whose elements are greater than a and less than b. 1 A half open interval [a, b) is the subset of R whose elements are greater than or equal to a and less than b. -

Linear Gaps Between Degrees for the Polynomial Calculus Modulo Distinct Primes

Linear Gaps Between Degrees for the Polynomial Calculus Modulo Distinct Primes Sam Buss1;2 Dima Grigoriev Department of Mathematics Computer Science and Engineering Univ. of Calif., San Diego Pennsylvania State University La Jolla, CA 92093-0112 University Park, PA 16802-6106 [email protected] [email protected] Russell Impagliazzo1;3 Toniann Pitassi1;4 Computer Science and Engineering Computer Science Univ. of Calif., San Diego University of Arizona La Jolla, CA 92093-0114 Tucson, AZ 85721-0077 [email protected] [email protected] Abstract e±cient search algorithms and in part by the desire to extend lower bounds on proposition proof complexity This paper gives nearly optimal lower bounds on the to stronger proof systems. minimum degree of polynomial calculus refutations of The Nullstellensatz proof system is a propositional Tseitin's graph tautologies and the mod p counting proof system based on Hilbert's Nullstellensatz and principles, p 2. The lower bounds apply to the was introduced in [1]. The polynomial calculus (PC) ¸ polynomial calculus over ¯elds or rings. These are is a stronger propositional proof system introduced the ¯rst linear lower bounds for polynomial calculus; ¯rst by [4]. (See [8] and [3] for subsequent, more moreover, they distinguish linearly between proofs over general treatments of algebraic proof systems.) In the ¯elds of characteristic q and r, q = r, and more polynomial calculus, one begins with an initial set of 6 generally distinguish linearly the rings Zq and Zr where polynomials and the goal is to prove that they cannot q and r do not have the identical prime factors. -

Gröbner Bases Tutorial

Gröbner Bases Tutorial David A. Cox Gröbner Basics Gröbner Bases Tutorial Notation and Definitions Gröbner Bases Part I: Gröbner Bases and the Geometry of Elimination The Consistency and Finiteness Theorems Elimination Theory The Elimination Theorem David A. Cox The Extension and Closure Theorems Department of Mathematics and Computer Science Prove Extension and Amherst College Closure ¡ ¢ £ ¢ ¤ ¥ ¡ ¦ § ¨ © ¤ ¥ ¨ Theorems The Extension Theorem ISSAC 2007 Tutorial The Closure Theorem An Example Constructible Sets References Outline Gröbner Bases Tutorial 1 Gröbner Basics David A. Cox Notation and Definitions Gröbner Gröbner Bases Basics Notation and The Consistency and Finiteness Theorems Definitions Gröbner Bases The Consistency and 2 Finiteness Theorems Elimination Theory Elimination The Elimination Theorem Theory The Elimination The Extension and Closure Theorems Theorem The Extension and Closure Theorems 3 Prove Extension and Closure Theorems Prove The Extension Theorem Extension and Closure The Closure Theorem Theorems The Extension Theorem An Example The Closure Theorem Constructible Sets An Example Constructible Sets 4 References References Begin Gröbner Basics Gröbner Bases Tutorial David A. Cox k – field (often algebraically closed) Gröbner α α α Basics x = x 1 x n – monomial in x ,...,x Notation and 1 n 1 n Definitions α ··· Gröbner Bases c x , c k – term in x1,...,xn The Consistency and Finiteness Theorems ∈ k[x]= k[x1,...,xn] – polynomial ring in n variables Elimination Theory An = An(k) – n-dimensional affine space over k The Elimination Theorem n The Extension and V(I)= V(f1,...,fs) A – variety of I = f1,...,fs Closure Theorems ⊆ nh i Prove I(V ) k[x] – ideal of the variety V A Extension and ⊆ ⊆ Closure √I = f k[x] m f m I – the radical of I Theorems { ∈ |∃ ∈ } The Extension Theorem The Closure Theorem Recall that I is a radical ideal if I = √I. -

Monomial Orderings, Rewriting Systems, and Gröbner Bases for The

Monomial orderings, rewriting systems, and Gr¨obner bases for the commutator ideal of a free algebra Susan M. Hermiller Department of Mathematics and Statistics University of Nebraska-Lincoln Lincoln, NE 68588 [email protected] Xenia H. Kramer Department of Mathematics Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Blacksburg, VA 24061 [email protected] Reinhard C. Laubenbacher Department of Mathematics New Mexico State University Las Cruces, NM 88003 [email protected] 0Key words and phrases. non-commutative Gr¨obner bases, rewriting systems, term orderings. 1991 Mathematics Subject Classification. 13P10, 16D70, 20M05, 68Q42 The authors thank Derek Holt for helpful suggestions. The first author also wishes to thank the National Science Foundation for partial support. 1 Abstract In this paper we consider a free associative algebra on three gen- erators over an arbitrary field K. Given a term ordering on the com- mutative polynomial ring on three variables over K, we construct un- countably many liftings of this term ordering to a monomial ordering on the free associative algebra. These monomial orderings are total well orderings on the set of monomials, resulting in a set of normal forms. Then we show that the commutator ideal has an infinite re- duced Gr¨obner basis with respect to these monomial orderings, and all initial ideals are distinct. Hence, the commutator ideal has at least uncountably many distinct reduced Gr¨obner bases. A Gr¨obner basis of the commutator ideal corresponds to a complete rewriting system for the free commutative monoid on three generators; our result also shows that this monoid has at least uncountably many distinct mini- mal complete rewriting systems. -

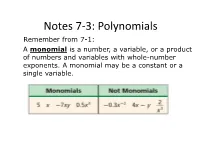

Polynomials Remember from 7-1: a Monomial Is a Number, a Variable, Or a Product of Numbers and Variables with Whole-Number Exponents

Notes 7-3: Polynomials Remember from 7-1: A monomial is a number, a variable, or a product of numbers and variables with whole-number exponents. A monomial may be a constant or a single variable. I. Identifying Polynomials A polynomial is a monomial or a sum or difference of monomials. Some polynomials have special names. A binomial is the sum of two monomials. A trinomial is the sum of three monomials. • Example: State whether the expression is a polynomial. If it is a polynomial, identify it as a monomial, binomial, or trinomial. Expression Polynomial? Monomial, Binomial, or Trinomial? 2x - 3yz Yes, 2x - 3yz = 2x + (-3yz), the binomial sum of two monomials 8n3+5n-2 No, 5n-2 has a negative None of these exponent, so it is not a monomial -8 Yes, -8 is a real number Monomial 4a2 + 5a + a + 9 Yes, the expression simplifies Monomial to 4a2 + 6a + 9, so it is the sum of three monomials II. Degrees and Leading Coefficients The terms of a polynomial are the monomials that are being added or subtracted. The degree of a polynomial is the degree of the term with the greatest degree. The leading coefficient is the coefficient of the variable with the highest degree. Find the degree and leading coefficient of each polynomial Polynomial Terms Degree Leading Coefficient 5n2 5n 2 2 5 -4x3 + 3x2 + 5 -4x2, 3x2, 3 -4 5 -a4-1 -a4, -1 4 -1 III. Ordering the terms of a polynomial The terms of a polynomial may be written in any order. However, the terms of a polynomial are usually arranged so that the powers of one variable are in descending (decreasing, large to small) order. -

Discriminants, Resultants, and Their Tropicalization

Discriminants, resultants, and their tropicalization Course by Bernd Sturmfels - Notes by Silvia Adduci 2006 Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Newton polytopes and tropical varieties 3 2.1 Polytopes . 3 2.2 Newton polytope . 6 2.3 Term orders and initial monomials . 8 2.4 Tropical hypersurfaces and tropical varieties . 9 2.5 Computing tropical varieties . 12 2.5.1 Implementation in GFan ..................... 12 2.6 Valuations and Connectivity . 12 2.7 Tropicalization of linear spaces . 13 3 Discriminants & Resultants 14 3.1 Introduction . 14 3.2 The A-Discriminant . 16 3.3 Computing the A-discriminant . 17 3.4 Determinantal Varieties . 18 3.5 Elliptic Curves . 19 3.6 2 × 2 × 2-Hyperdeterminant . 20 3.7 2 × 2 × 2 × 2-Hyperdeterminant . 21 3.8 Ge’lfand, Kapranov, Zelevinsky . 21 1 4 Tropical Discriminants 22 4.1 Elliptic curves revisited . 23 4.2 Tropical Horn uniformization . 24 4.3 Recovering the Newton polytope . 25 4.4 Horn uniformization . 29 5 Tropical Implicitization 30 5.1 The problem of implicitization . 30 5.2 Tropical implicitization . 31 5.3 A simple test case: tropical implicitization of curves . 32 5.4 How about for d ≥ 2 unknowns? . 33 5.5 Tropical implicitization of plane curves . 34 6 References 35 2 1 Introduction The aim of this course is to introduce discriminants and resultants, in the sense of Gel’fand, Kapranov and Zelevinsky [6], with emphasis on the tropical approach which was developed by Dickenstein, Feichtner, and the lecturer [3]. This tropical approach in mathematics has gotten a lot of attention recently in combinatorics, algebraic geometry and related fields. -

Florida Math 0028 Correlation of the ALEKS Course Florida

Florida Math 0028 Correlation of the ALEKS course Florida Math 0028 to the Florida Mathematics Competencies - Upper Exponents & Polynomials = ALEKS course topic that addresses the standard MDECU1: Applies the order of operations to evaluate algebraic expressions, including those with parentheses and exponents Order of operations with whole numbers Order of operations with whole numbers and grouping symbols Order of operations with whole numbers and exponents: Basic Order of operations with whole numbers and exponents: Advanced Evaluating an algebraic expression: Whole number operations and exponents Absolute value of a number Operations with absolute value Exponents and integers: Problem type 1 Exponents and integers: Problem type 2 Exponents and signed fractions Order of operations with integers and exponents Evaluating a linear expression: Integer multiplication with addition or subtraction Evaluating a quadratic expression: Integers Evaluating a linear expression: Signed fraction multiplication with addition or subtraction Evaluating a linear expression: Signed decimal addition and subtraction Evaluating a linear expression: Signed decimal multiplication with addition or subtraction Combining like terms: Whole number coefficients Combining like terms: Integer coefficients Multiplying a constant and a linear monomial Distributive property: Whole number coefficients Distributive property: Integer coefficients Using distribution and combining like terms to simplify: Univariate Using distribution with double negation and combining like terms to simplify: Multivariate Combining like terms in a quadratic expression MDECU2: Simplifies an expression with integer exponents Understanding the product rule of exponents Introduction to the product rule of exponents Product rule with positive exponents: Univariate Product rule with positive exponents: Multivariate Understanding the power rules of exponents (FF4)Copyright © 2014 UC Regents and ALEKS Corporation. -

Gröbner Bases Victor Adamchik Carnegie Mellon University

15-355: Modern Computer Algebra 1 Gröbner Bases Victor Adamchik Carnegie Mellon University à The main idea Given a system of polynomial equations f1 = 0 ... fs = 0 It forms an ideal I = < f1, ..., fs > for which we cannot solve a membership problem It's better to choose a monomial ideal But how would you build a monomial ideal out of a given set of polynomials? Monomial Ideal à Understanding the structure Definition: A monomial ideal I Ì R is an ideal generated by monomials in R. For example, I = < x2 y5, x4 y3, x5 y > a Such an ideal I consists of all polynomials which are finite sums of qa x , where qk Î R. We will a n write I = x , a Î A Ì Z³0 Example. Given Ú 8 < I = < x2, x y3, y4 z, x y z > Then f = 3 x7 + 7 x y3 z + 2 y4 z + x y2 z2 is in I, since x7 = x2 x5 x y3 z = x y3 z x y2 z2 =I xMyIz M y z I M H L H L H L 2 Groebner Bases x7 = x2 x5 8 x y3 z = x y3 z 7 x y2 z2 = x y z y z 6 I M I M Exercise. Given 5 I M H L 4 I = < x3, Hx2 y >L H L 3 Verify 2 4 2 3 1 f1 = 3 x + 5 x y is it in I? 2 3 4 5 4 6 2 7 8 f2 = 2 x y + 7 x is it in I? Lemma. -

Discriminants, Symmetrized Graph Monomials, and Sums of Squares

DISCRIMINANTS, SYMMETRIZED GRAPH MONOMIALS, AND SUMS OF SQUARES PER ALEXANDERSSON AND BORIS SHAPIRO Abstract. Motivated by the necessities of the invariant theory of binary forms J. J. Sylvester constructed in 1878 for each graph with possible mul- tiple edges but without loops its symmetrized graph monomial which is a polynomial in the vertex labels of the original graph. We pose the question for which graphs this polynomial is a non-negative resp. a sum of squares. This problem is motivated by a recent conjecture of F. Sottile and E. Mukhin on discriminant of the derivative of a univariate polynomial, and an interesting example of P. and A. Lax of a graph with 4 edges whose symmetrized graph monomial is non-negative but not a sum of squares. We present detailed in- formation about symmetrized graph monomials for graphs with four and six edges, obtained by computer calculations. 1. Introduction In what follows by a graph we will always mean a (directed or undirected) graph with (possibly) multiple edges but no loops. The classical construction of J. J. Sylvester and J. Petersen [8, 9] associates to an arbitrary directed loopless graph a symmetric polynomial as follows. Definition 1. Let g be a directed graph, with vertices x1; : : : ; xn and adjacency matrix (aij); where aij is the number of directed edges connecting xi and xj: Define its graph monomial Pg as Y aij Pg(x1; : : : ; xn) := (xi − xj) : 1≤i;j≤n The symmetrized graph monomial of g is defined as X g~(x) = Pg(σx); x = x1; : : : ; xn: σ2Sn Notice that if the original g is undirected one can still defineg ~ up to a sign by choosing an arbitrary orientation of its edges. -

Determine Whether Each Expression Is a Polynomial

8-1 Adding and Subtracting Polynomials Determine whether each expression is a polynomial. If it is a polynomial, find the degree and determine whether it is a monomial, binomial, or trinomial. 2 3 1. 7ab + 6b – 2a ANSWER: yes; 3; trinomial 2. 2y – 5 + 3y2 ANSWER: yes; 2; trinomial 2 3. 3x ANSWER: yes; 2; monomial 4. ANSWER: No; a monomial cannot have a variable in the denominator. 5. 5m2p 3 + 6 ANSWER: yes; 5; binomial –4 6. 5q + 6q ANSWER: No; , and a monomial cannot have a variable in the denominator. Write each polynomial in standard form. Identify the leading coefficient. 7. –4d4 + 1 – d2 ANSWER: 4 2 –4d – d + 1; –4 8. 2x5 – 12 + 3x ANSWER: 5 2x + 3x – 12 ; 2 9. 4z – 2z2 – 5z4 eSolutionsANSWER: Manual - Powered by Cognero Page 1 4 2 –5z – 2z + 4z; –5 10. 2a + 4a3 – 5a2 – 1 ANSWER: 3 2 4a – 5a + 2a – 1, 4 Find each sum or difference. 11. (6x3 − 4) + (−2x3 + 9) ANSWER: 3 4x + 5 12. (g3 − 2g2 + 5g + 6) − (g2 + 2g) ANSWER: 3 2 g − 3g + 3g + 6 13. (4 + 2a2 − 2a) − (3a2 − 8a + 7) ANSWER: 2 −a + 6a − 3 14. (8y − 4y2) + (3y − 9y2) ANSWER: 2 −13y + 11y 15. (−4z3 − 2z + 8) − (4z3 + 3z2 − 5) ANSWER: 3 2 −8z − 3z − 2z + 13 16. (−3d2 − 8 + 2d) + (4d − 12 + d2) ANSWER: 2 −2d + 6d − 20 17. (y + 5) + (2y + 4y2 – 2) ANSWER: 2 4y + 3y + 3 18. (3n3 − 5n + n2) − (−8n2 + 3n3) ANSWER: 2 9n − 5n 19. CCSS SENSE-MAKING The total number of students T who traveled for spring break consists of two groups: students who flew to their destinations F and students who drove to their destination D. -

Lesson 7.1 – Factoring Polynomials I

LESSON 7.1 – FACTORING POLYNOMIALS I LESSON 7.1 FACTORING POLYNOMIALS I 293 OVERVIEW Here’s what you’ll learn in this lesson: You have learned how to multiply polynomials. Now you will learn how to factor them. Greatest Common Factor When you factor a polynomial, you write it as the product of other polynomials. a. Finding the greatest common factor In this lesson you will learn several different techniques for factoring polynomials. (GCF) of a set of monomials b. Factoring a polynomial by finding the GCF when the GCF is a monomial Grouping a. Factoring a polynomial by finding the GCF when the GCF is a binomial b. Factoring a polynomial with four terms by grouping 294 TOPIC 7 FACTORING EXPLAIN GREATEST COMMON FACTOR Summary Factoring Polynomials You already know how to factor numbers by writing them as the product of other numbers. Now you will learn how to factor polynomials by writing them as the product of other polynomials. Finding the GCF of a Collection of Monomials To find the GCF of a collection of monomials: Remember that a monomial is a polynomial with only one term. For 1. Factor each monomial into its prime factors. example: 14x 5y 3, 32, 6x, and 9xyz are 2. List each common prime factor the smallest number of times it appears in monomials; but 12x 5y + 1 and 14y + 3x any factorization. are not monomials. 3. Multiply all the prime factors in the list. Before deciding if a polynomial is a monomial, binomial, etc., be sure you For example, to find the GCF of the monomials 16x 2y 2, 4x 3y 2, and 12xy 4 : first combine any like terms and apply 1. -

Eight Lectures on Monomial Ideals Contents

COCOA Summer School 1999 Eight Lectures on Monomial Ideals ezra miller david perkinson Contents Preface 2 Acknowledgments............................. 4 0 Basics 4 0.1 Zn-grading................................. 4 0.2 Monomialmatrices ............................ 5 0.3 Complexesandresolutions . 6 0.4 Hilbertseries ............................... 7 0.5 Simplicial complexes and homology . 8 0.6 Irreducibledecomposition . 10 1 Lecture I: Squarefree monomial ideals 11 1.1 Equivalent descriptions . 11 1.2 Hilbertseries ............................... 12 1.3 Freeresolutions .............................. 14 2 Lecture II: Borel-fixed monomial ideals 17 2.1 Groupactions............................... 17 2.2 Genericinitialideals ........................... 18 2.3 TheEliahou-Kervaireresolution . .. 18 2.4 Lex-segmentideals ............................ 21 3 Lecture III: Monomial ideals in three variables 21 3.1 Monomial ideals in two variables . 22 3.2 Buchberger’ssecondcriterion . 23 3.3 Resolution“bypicture” . .. .. 24 3.4 Planargraphs............................... 25 3.5 Reducing to the squarefree or Borel-fixed case . .... 27 4 Lecture IV: Generic monomial ideals 27 4.1 TheScarfcomplex ............................ 28 4.2 Deformationofexponents . 30 4.3 Triangulatingthesimplex . 31 1 5 Lecture V: Cellular Resolutions 33 5.1 Thebasicconstruction .......................... 33 5.2 Exactness of cellular complexes . 34 5.3 Examples of cellular resolutions . .. 36 5.4 Thehullresolution ............................ 37 6 Lecture VI: Alexander duality