The Evolution of Bitless Equitation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effortless. All Flat Shod Pleasure Entries Should Have Comfortable Gaits; Giving the Distinct Impression It Is an Agreeable Mount to Ride

effortless. All Flat Shod Pleasure entries should have comfortable gaits; giving the distinct impression it is an agreeable mount to ride. The Flat Shod Pleasure horse should be effortless in their motion and for their rider. The Flat Shod Pleasure classes are to be judged on true pleasure qualities and the performance of the horse. Talent should be rewarded in this division. Neatness and appearance of the horse and exhibitor and conformation of the horse should be a consideration in final judging. All Flat Shod Pleasure entries must stand quietly in the lineup and back readily. The judge must walk the line-up in all flat shod classes and ask each entry to back individually. Any entry that leans back on its haunches and drags both front feet instead of picking them up individually to back must be heavily penalized. Also, the flat shod horse that refuses to back cannot be placed over a horse that does back in the final judging. If any horse that has been judged comes out of a class line up presenting a non-standard image (See Standards Chart), the judge(s) must report the class and entry number to SHOW and a letter of warning will be sent to the trainer. English flat shod pleasure entries must be ridden with a light/relaxed rein at all gaits. Western flat shod entries must be ridden on a loose rein at all gaits. Loose reins along with neck reining and a lower head set are the main factors differentiating the Western flat shod horse from the English flat shod horse. -

User's Manual

USER’S MANUAL The Bitless Bridle, Inc. email: [email protected] Phone: 719-576-4786 5220 Barrett Rd. Fax: 719-576-9119 Colorado Springs, Co. 80926 Toll free: 877-942-4277 IMPORTANT: Read the fitting instructions on pages four and five before using. Improper fitting can result in less effective control. AVOIDANCE OF ACCIDENTS Nevertheless, equitation is an inherently risky activity and The Bitless Bridle, Inc., can accept no responsibility for any accidents that might occur. CAUTION Observe the following during first time use: When first introduced to the Bitless Bridle™, it sometimes revives a horse’s spirits with a feeling of “free at last”. Such a display of exuberance will eventually pass, but be prepared for the possibility even though it occurs in less than 1% of horses. Begin in a covered school or a small paddock rather than an open area. Consider preliminary longeing or a short workout in the horse’s normal tack. These and other strategies familiar to horse people can be used to reduce the small risk of boisterous behavior. APPLICATION The action of this bridle differs fundamentally from all other bitless bridles (the hackamores, bosals, and sidepulls). By means of a simple but subtle system of two loops, one over the poll and one over the nose, the bridle embraces the whole of the head. It can be thought of as providing the rider with a benevolent headlock on the horse (See illustration below) . Unlike the bit method of control, the Bitless Bridle is compatible with the physiological needs of the horse at excercise. -

Horse Racing Tack for the Hivewire (HW3D) Horse by Ken Gilliland Horse Racing, the Sport of Kings

Horse Racing Tack for the HiveWire (HW3D) Horse by Ken Gilliland Horse Racing, the Sport of Kings Horse racing is a sport that has a long history, dating as far back as ancient Babylon, Syria, and Egypt. Events in the first Greek Olympics included chariot and mounted horse racing and in ancient Rome, both of these forms of horse racing were major industries. As Thoroughbred racing developed as a sport, it became popular with aristocrats and royalty and as a result achieved the title "Sport of Kings." Today's horse racing is enjoyed throughout the world and uses several breeds of horses including Thoroughbreds and Quarter Horses in the major race track circuit, and Arabians, Paints, Mustangs and Appaloosas on the County Fair circuit. There are four types of horse racing; Flat Track racing, Jump/Steeplechase racing, Endurance racing and Harness racing. “Racehorse Tack” is designed for the most common and popular type of horse racing, Flat Track. Tracks are typically oval in shape and are level. There are exceptions to this; in Great Britain and Ireland there are considerable variations in shape and levelness, and at Santa Anita (in California), there is the famous hillside turf course. Race track surfaces can vary as well with turf being the most common type in Europe and dirt more common in North America and Asia. Newer synthetic surfaces, such as Polytrack or Tapeta, are also seen at some tracks. Individual flat races are run over distances ranging from 440 yards (400 m) up to two and a half miles, with distances between five and twelve furlongs being most common. -

Read Book Through England on a Side-Saddle Ebook, Epub

THROUGH ENGLAND ON A SIDE-SADDLE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Celia Fiennes | 96 pages | 02 Apr 2009 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780141191072 | English | London, United Kingdom Sidesaddle - Wikipedia Ninth century depictions show a small footrest, or planchette added to the pillion. In Europe , the sidesaddle developed in part because of cultural norms which considered it unbecoming for a woman to straddle a horse while riding. This was initially conceived as a way to protect the hymen of aristocratic girls, and thus the appearance of their being virgins. However, women did ride horses and needed to be able to control their own horses, so there was a need for a saddle designed to allow control of the horse and modesty for the rider. The earliest functional "sidesaddle" was credited to Anne of Bohemia — The design made it difficult for a woman to both stay on and use the reins to control the horse, so the animal was usually led by another rider, sitting astride. The insecure design of the early sidesaddle also contributed to the popularity of the Palfrey , a smaller horse with smooth ambling gaits, as a suitable mount for women. A more practical design, developed in the 16th century, has been attributed to Catherine de' Medici. In her design, the rider sat facing forward, hooking her right leg around the pommel of the saddle with a horn added to the near side of the saddle to secure the rider's right knee. The footrest was replaced with a "slipper stirrup ", a leather-covered stirrup iron into which the rider's left foot was placed. -

The Dog Scout Scoop

The Dog Scout Scoop Official Newsletter ~ Dog Scouts of America Published for DSA’s responsible dog-loving members and for the friends of dogs everywhere Volume 20 Issue 5 September/October 2017 FYI: Troop 219 is collecting donations for pet victims of Rainbow Hurricane Harvey and Irma. Bridge Contact Kelly Ford if you’d like to donate: P2 [email protected] Photo: Wendy Nugent Teaching Trail Etiquette to Dogs P7-9 Badge Bulletin & Title Tales P4-6 Scout Scoop Attitude of & Troop Talk Gratitude P10-39 P40 Deadline: for the next newsletter is November 15th Please e-mail your news, articles, and pictures to [email protected] STAY TUNED . UPDATES WILL BE POSTED ON OUR WEBSITE, FACEBOOK PAGE AND E-MAILED TO THE YAHOO LISTS. Page 2 The Dog Scout Scoop Rainbow Bridge It is with great sadness that we share news of the You don’t want to miss this one! The 2017 Jam- passing of one of boree will take place October 20-22. You don’t troop 157’s need a team to join us, just a sense of humor, an active imagination and an expectation that you longest standing will have an unforgettable adventure as you work members. Bella, with others to ESCAPE! the beloved Sheltie of Alice The weekend will be packed with games and ac- Perez passed tivities based on urban legends. Then, you’ll take away after a 3- the clues you gathered during the weekend and month battle with work with others, applying the information you’ve lung cancer. Bella gathered to the Sunday morning “lock in”. -

MU Guide PUBLISHED by MU EXTENSION, UNIVERSITY of MISSOURI-COLUMBIA Muextension.Missouri.Edu

Horses AGRICULTURAL MU Guide PUBLISHED BY MU EXTENSION, UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI-COLUMBIA muextension.missouri.edu Choosing, Assembling and Using Bridles Wayne Loch, Department of Animal Sciences Bridles are used to control horses and achieve desired performance. Although horses can be worked without them or with substitutes, a bridle with one or two bits can add extra finesse. The bridle allows you to communicate and control your mount. For it to work properly, you need to select the bridle carefully according to the needs of you and your horse as well as the type of performance you expect. It must also be assembled correctly. Although there are many styles of bridles, the procedures for assembling and using them are similar. The three basic parts of a bridle All bridles have three basic parts: bit, reins and headstall (Figure 1). The bit is the primary means of communication. The reins allow you to manipulate the bit and also serve as a secondary means of communica- tion. The headstall holds the bit in place and may apply Figure 1. A bridle consists of a bit, reins and headstall. pressure to the poll. The bit is the most important part of the bridle The cheekpieces and shanks of curb and Pelham bits because it is the major tool of communication and must also fit properly. If the horse has a narrow mouth control. Choose one that is suitable for the kind of perfor- and heavy jaws, you might bend them outward slightly. mance you desire and one that is suitable for your horse. Cheekpieces must lie along the horse’s cheeks. -

Leave No Trace: Outdoor Skills and Ethics- Backcountry Horse

Leave No Trace: Outdoor Skills and Ethics Backcountry Horse Use The Leave No Trace program teaches and develops practical conservation techniques designed to minimize the "impact" of visitors on the wilderness environment. "Impact" refers to changes visitors create in the backcountry, such as trampling of fragile vegetation or pollution of water sources. The term may also refer to social impacts-- behavior that diminishes the wilderness experience of other visitors. Effective minimum-impact practices are incorporated into the national Leave No Trace education program as the following Leave No Trace Principles. Principles of Leave No Trace · Plan Ahead and Prepare · Concentrate Use in Resistant Areas · Avoid Places Where Impact is Just Beginning · Pack It In, Pack It Out · Properly Dispose of What You Can't Pack Out · Leave What You Find · Use Fire Responsibly These principles are a guide to minimizing the impact of your backcountry visits to America's arid regions. This booklet discusses the rationale behind each principle to assist the user in selecting the most appropriate techniques for the local environment. Before traveling into the backcountry, we recommend that you check with local officials of the Forest Service, Park Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Land Management or other managing agency for advice and regulations specific to the area you will be traveling in. First and foremost, it is important to carefully review and follow all agency regulations and recommendations; these materials support and complement agency guidelines .Minimizing our impact on the backcountry depends more on attitude and awareness than on rules and regulations. Leave No Trace camping practices must be flexible and tempered by judgment and experience. -

Rolled Show Cattle Halter

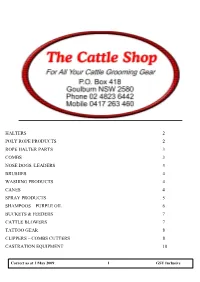

HALTERS 2 POLY ROPE PRODUCTS 2 ROPE HALTER PARTS 3 COMBS 3 NOSE DOGS /LEADERS 3 BRUSHES 4 WASHING PRODUCTS 4 CANES 4 SPRAY PRODUCTS 5 SHAMPOOS – PURPLE OIL 6 BUCKETS & FEEDERS 7 CATTLE BLOWERS 7 TATTOO GEAR 8 CLIPPERS – COMBS CUTTERS 8 CASTRATION EQUIPMENT 10 Correct as at 1 May 2009 1 GST Inclusive The Cattle Shop Phone 02 4823 6442 Product Catalogue www.thecattleshop.com.au Leather Cattle Lead with snap – A 1.5m strong HALTERS quality leather lead with solid brass that can be matched with any cattle halter. Australian made Rolled Available in Black or Brown Leather Halters. Black or Price $12.50 Brown Leather With brass or nickel fittings Leather Cattle Lead with Chain – nickel plated Bull – chain and snap overall length 223cm. Cow – Price $18.00 Heifer and Calf sizes. POLY ROPE PRODUCTS Price: $ 130.00 Poly Rope Halter, Neck Ties Deluxe Rolled Show Halter – INDIAN LEATHER and Lead Ropes -Made from Complete lead-in set with strong poly rope solid brass chain on lead. Available in Black, Red, Blue, Brass fittings and separate Green or Maroon brass lead and snap. Sturdy Halter - $19.95 and strong rolled leather. Available in Brown or Black / Neck Tie – Ideal for securing animals at shows. Solid Brass brass snap hook Small -Medium - Large Price 29.95 All One Price $65.00 Cattle Lead Strong poly rope lead 185cm long with solid brass Indian Leather Halter Black snap hook with Stainless steel hardware Price $17.95 and a rolled noseband comes complete with 2 stainless steel Fluro Halters – leads Small, Medium and Large Available in $84.95 Purple/Black, Pink/Black, Green/White, Green/Pink Leather Halter Brown with and Black/Orange Brass, soft and supple yet strong $15.95 these 1” brown oiled leather cattle halters have solid brass hardware Solid Colour halters – and a rolled noseband comes in Blue, Black, Purple, complete with 2 leads Green and Red. -

Harness Driving Manual and Rules for Washington State

EM4881 HARNESS DRIVING MANUAL AND RULES FOR WASHINGTON STATE 4-H harness driving rules 1 WASHINGTON 4-H YOUTH DEVELOPMENT POLICY FOR PROTECTIVE HEADGEAR USE IN THE 4-H EQUINE PROGRAM Equestrian Helmets. All Washington 4-H members and non-member youth participating in all equine projects and activities must wear American Society of Testing Materials (ASTM) and Safety Engineer- ing Institute (SEI) approved headgear when riding or driving. The headgear must have a chin strap and be properly fitted. Additionally, all equestrians (including adults) are strongly encouraged to wear protective headgear at all times when riding or working around horses. 2 4-H harness driving rules ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This publication was developed through the assistance of many knowledge- able 4-H supporters. Thanks go to: Gladys Cluphf Larry Colburn Yvonne Gallentine Isabelle Moe Ivadelle Nordheim Arnold and Shirley Odegaard LaVon Read Adapted by: Pat Pehling, Snohomish County 4-H Volunteer Jerry A. Newman, Cooperative Extension Youth Development Specialist A special thanks to Isabelle Moe and LaVon Read for this updated version. Some illustrations and text were adapted from PNW229, 4-H Horse and Pony Driving Manual, published by Oregon State University. 4-H harness driving rules 3 4 4-H harness driving rules CONTENTS APPOINTMENTS ...................................................................................................... 7 GENERAL RULES ..................................................................................................... 7 DRIVING CLASSES -

Bosal and Hackamores-Think Like a Horse-Rick Gore Horsemanship®

Bosal and Hackamores-Think Like a Horse-Rick Gore Horsemanship® *Home Horse's love it when their owner's understand them. *Sitemap Horsemanship is about the horse teaching you about yourself. *SEARCH THE SITE *Horse History *Horseman Tips *Horsemanship *Amazing Horse Hoof *Horse Anatomy Pictures Care and Cleaning of Bosal and Rawhide *Rope Halters No discussion of the Bosal and Hackamore would be complete My Random Horse without mentioning, Ed Connell. His books about using, starting and training with the Hackamore are from long ago and explain things Thoughts well. If you want to completely understand the Bosal and Hackamore, his books explain it in detail. *Tying A Horse Bosals and Hackamores were originally used to start colts in training. Since untrained colts make many mistakes, a hackamore *Bosal/Hackamores does not injure sensitive tissue in the colt's mouth and provides firm and safe control. The term Hackamore and Bosal are interchangeable, however, technically the *Bad Horsemanship Bosal is only the rawhide braid around the nose of the horse. The hanger and reins together with the Bosal completes the Hackamore. *Misc Horse Info Parts of a Hackamore :Hackamore came from Spanish culture and was derived from the *Trailer Loading Spanish word jaquima (hak-kee-mah). The parts of the Hackamore are: *Training Videos Bosal (boz-al):This is the part around the horse's nose usually made of braided rawhide, but it can be made of leather, horsehair or rope. The size and thickness of the *Hobbles bosal can vary from pencil size (thin) to 5/8 size (thick). -

Product Catalogue 1

Leading Brand in Harness & Accessories Product Catalogue 1 www.idealequestrian.com Ideal Equestrian Quality and reassurance Since 1994 Ideal Equestrian has been developing and producing a wide range of driving harness and accessories. The standard of our harness is our no.1 priority and together with successful national and international drivers, we are constantly improving in the design and technology of our products. Our harness ranges from a luxury traditional leather presentation 2 harness with full collar, to a marathon or high-tech synthetic EuroTech harness. Ideal has it all! This catalogue is just a selection of our products. Visit our website and view our full range, and discover what Ideal Equestrian has to offer you. www.idealequestrian.com LEADING BRAND IN HARNESS & ACCESSORIES Index HARNESS Luxe 4 Marathon 6 LeatherTech Combi 8 EuroTech Classic 12 3 EuroTech Combi 14 WebTech Combi 16 Ideal Friesian 18 Ideal Heavy horse 18 Harness Parts 19 Driving Accessories 20 Luxe • Traditional Classic Harness • High Quality Leather • Elegant appearance Sizes available: Full / Cob / Pony / Shetland / Mini Shetland 4 Leather LeatherLeather Leather Black Black/ London Australian Nut Luxe Options – Single: - Breast collar with continuous traces This traditionally made quality harness is perfect for all disciplines of carriage driving, durable enough (adjustment at carriage end) for tough conditions yet attractive for presentation. Nylon webbing is stitched between the leather where extra strength is needed. The saddle pad has foam filled cushions, holes are oval to prevent - Traces with Rollerbolt or Crew hole tearing and all buckles have stainless steel tongues. Nose band is fully adjustable and headpiece is - Leather Reins tapered in the middle to create more freedom around the ears. -

Dover Saddlery® Nameplates a Personalized Nameplate Identifies Your Horse Or Pony's Tack, Stall Or SADDLE PLATES Other Equipment in Style

Dover Saddlery® Nameplates A personalized nameplate identifies your horse or pony's tack, stall or SADDLE PLATES other equipment in style. Choose from brass and German silver plates in 3 Fancy Saddle Plate - 2½" x /8" a classic or contemporary style. Each will be engraved in the USA in Brass German Silver your choice of Block, Old English, Roman or Script letters.* #32307 ............................ $10.95 3 2" Fancy Saddle Plate - 2" x /8" #32301 (Brass only) ........ $11.95 Beveled Edge Saddle Plate - 2½" x ½". #32302 (Brass only) ........ $13.95 Beveled Notched Corner Saddle Plate - 2½" x ½" #32363 (Brass only) ........ $14.95 MISCELLANEOUS PLATES HALTER PLATES Rectangular Dog Collar Plate - 2½" x ½" Rectangular Halter Plate - 4½" x ¾" #32325 (Brass only) ........ $14.95 Brass German Silver 3 1 or 2 lines ....................#32304 $15.95 Belt Nameplate - 2½" x /8" 3 lines ........................ #32316 $17.95 Brass German Silver Beveled Edge Halter Plate - 4½" x ¾" #4139 .............................. $10.95 Brass German Silver Beveled 1 or 2 lines .................. #32315 $15.95 PLASTIC NAMEPLATES 3 lines ........................ #32317 $18.95 Plastic Stall Plate - 2" x 8" Fancy Halter Plate - 4½" x ¾" With pre-drilled holes. Please specify if Brass German Silver holes are not needed. 1 or 2 lines .................. #32318 $15.95 3 lines ........................ #32319 $18.95 1 or 2 lines .................. #32306 $21.95 Notched Corner Halter Plate - 4½" x ¾" 3 lines ........................ #32327 $24.95 Brass German Silver Plastic Stall Plate With Holder 1 or 2 lines ..........................#32366 $15.95 Plate slides into gold tone holder, Small Rectangular Halter Plate - 3½" x ½" which mounts on door. 2" x 8".