Introduction Disney's Purchase of Lucasfilm in 2012 Heralded a New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 CSR Report

2019 CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY UPDATE Table of Contents 3 LETTER FROM OUR EXECUTIVE CHAIRMAN 21 CONTENT & PRODUCTS 4 OUR BUSINESS 26 SOCIAL IMPACT 5 OUR APPROACH AND GOVERNANCE 32 LOOKING AHEAD 7 ENVIRONMENT 33 DATA AND PERFORMANCE FY19 Highlights and Recognition ........ 34 12 WORKFORCE FY19 Performance on Targets .............. 35 FY19 Data Table ..................................... 36 18 SUPPLY CHAIN LABOR STANDARDS Sustainable Development Goals ......... 39 Global Reporting Initiative Index ......... 40 Intro Our Approach and Governance Environment Workforce Supply Chain Labor Standards Content & Products Social Impact Looking Ahead Data and Performance 2 LETTER FROM OUR EXECUTIVE CHAIRMAN through our Disney Aspire program, our nation’s At Disney, we also strive to have a positive impact low-carbon fuel sources, renewable electricity, and most comprehensive corporate education in our communities and on the world. This past year, natural climate solutions. I’m particularly proud of investment program, which gives employees the continuing a cause that dates back to Walt Disney the new 270-acre, 50+-megawatt solar facility that ability to pursue higher education, free of charge. himself, we took the next steps in our $100 million we brought online in Orlando. This new facility is This past year, more than half of our 94,000-plus commitment to deliver comfort and inspiration to able to generate enough clean energy to power hourly employees in the U.S. took the initial step to families with children facing serious illness using the two of the four theme parks at Walt Disney World, participate in Disney Aspire, and more than 12,000 powerful combination of our beloved characters reducing tens of thousands of tons of greenhouse enrolled in classes. -

The Development and Validation of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (Guess)

THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) A Dissertation by Mikki Hoang Phan Master of Arts, Wichita State University, 2012 Bachelor of Arts, Wichita State University, 2008 Submitted to the Department of Psychology and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 © Copyright 2015 by Mikki Phan All Rights Reserved THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a major in Psychology. _____________________________________ Barbara S. Chaparro, Committee Chair _____________________________________ Joseph Keebler, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jibo He, Committee Member _____________________________________ Darwin Dorr, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Member Accepted for the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences _____________________________________ Ronald Matson, Dean Accepted for the Graduate School _____________________________________ Abu S. Masud, Interim Dean iii DEDICATION To my parents for their love and support, and all that they have sacrificed so that my siblings and I can have a better future iv Video games open worlds. — Jon-Paul Dyson v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Althea Gibson once said, “No matter what accomplishments you make, somebody helped you.” Thus, completing this long and winding Ph.D. journey would not have been possible without a village of support and help. While words could not adequately sum up how thankful I am, I would like to start off by thanking my dissertation chair and advisor, Dr. -

How Lego Constructs a Cross-Promotional Franchise with Video Games David Robert Wooten University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2013 How Lego Constructs a Cross-promotional Franchise with Video Games David Robert Wooten University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Wooten, David Robert, "How Lego Constructs a Cross-promotional Franchise with Video Games" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 273. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/273 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW LEGO CONSTRUCTS A CROSS-PROMOTIONAL FRANCHISE WITH VIDEO GAMES by David Wooten A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Media Studies at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee August 2013 ABSTRACT HOW LEGO CONSTRUCTS A CROSS-PROMOTIONAL FRANCHISE WITH VIDEO GAMES by David Wooten The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2013 Under the Supervision of Professor Michael Newman The purpose of this project is to examine how the cross-promotional Lego video game series functions as the site of a complex relationship between a major toy manufacturer and several media conglomerates simultaneously to create this series of licensed texts. The Lego video game series is financially successful outselling traditionally produced licensed video games. The Lego series also receives critical acclaim from both gaming magazine reviews and user reviews. By conducting both an industrial and audience address study, this project displays how texts that begin as promotional products for Hollywood movies and a toy line can grow into their own franchise of releases that stills bolster the original work. -

First Person Shooting (FPS) Game

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056 Volume: 05 Issue: 04 | Apr-2018 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 Thunder Force - First Person Shooting (FPS) Game Swati Nadkarni1, Panjab Mane2, Prathamesh Raikar3, Saurabh Sawant4, Prasad Sawant5, Nitesh Kuwalekar6 1 Head of Department, Department of Information Technology, Shah & Anchor Kutchhi Engineering College 2 Assistant Professor, Department of Information Technology, Shah & Anchor Kutchhi Engineering College 3,4,5,6 B.E. student, Department of Information Technology, Shah & Anchor Kutchhi Engineering College ----------------------------------------------------------------***----------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract— It has been found in researches that there is an have challenged hardware development, and multiplayer association between playing first-person shooter video games gaming has been integral. First-person shooters are a type of and having superior mental flexibility. It was found that three-dimensional shooter game featuring a first-person people playing such games require a significantly shorter point of view with which the player sees the action through reaction time for switching between complex tasks, mainly the eyes of the player character. They are unlike third- because when playing fps games they require to rapidly react person shooters in which the player can see (usually from to fast moving visuals by developing a more responsive mind behind) the character they are controlling. The primary set and to shift back and forth between different sub-duties. design element is combat, mainly involving firearms. First person-shooter games are also of ten categorized as being The successful design of the FPS game with correct distinct from light gun shooters, a similar genre with a first- direction, attractive graphics and models will give the best person perspective which uses light gun peripherals, in experience to play the game. -

Nordic Game Is a Great Way to Do This

2 Igloos inc. / Carcajou Games / Triple Boris 2 Igloos is the result of a joint venture between Carcajou Games and Triple Boris. We decided to use the complementary strengths of both studios to create the best team needed to create this project. Once a Tale reimagines the classic tale Hansel & Gretel, with a twist. As you explore the magical forest you will discover that it is inhabited by many characters from other tales as well. Using real handmade puppets and real miniature terrains which are then 3D scanned to create a palpable, fantastic world, we are making an experience that blurs the line between video game and stop motion animated film. With a great story and stunning visuals, we want to create something truly special. Having just finished our prototype this spring, we have already been finalists for the Ubisoft Indie Serie and the Eidos Innovation Program. We want to validate our concept with the European market and Nordic Game is a great way to do this. We are looking for Publishers that yearn for great stories and games that have a deeper meaning. 2Dogs Games Ltd. Destiny’s Sword is a broad-appeal Living-Narrative Graphic Adventure where every choice matters. Players lead a squad of intergalactic peacekeepers, navigating the fallout of war and life under extreme circumstances, while exploring a breath-taking and immersive world of living, breathing, hand-painted artwork. Destiny’s Sword is filled with endless choices and unlimited possibilities—we’re taking interactive storytelling to new heights with our proprietary Insight Engine AI technology. This intricate psychology simulation provides every character with a diverse personality, backstory and desires, allowing them to respond and develop in an incredibly human fashion—generating remarkable player engagement and emotional investment, while ensuring that every playthrough is unique. -

THE DISNEY COMPANY | Disney, Lucasfilm, Marvel, Pixar, Touchstone

THE DISNEY COMPANY | Disney, Lucasfilm, Marvel, Pixar, Touchstone Smoking in Movies The Walt Disney Company actively limits the depiction of smoking in movies marketed to youth. Our practices currently include the following: • Disney has determined not to depict cigarette smoking in movies produced by it after 2015 (2007 in the case of Disney branded movies) and distributed under the Disney, Pixar, Marvel or Lucasfilm labels, that are rated G, PG or PG-13, except for scenes that: . depict a historical figure who may have smoked at the time of his or her life; or . portray cigarette smoking in an unfavorable light or emphasize the negative consequences of smoking. • Disney policy prohibits product placement or promotion deals with respect to tobacco products for any movie it produces and Disney includes a statement to this effect on any movie in which tobacco products are depicted for which Disney is the sole or lead producer. • Disney will place anti-smoking public service announcements on DVDs of its new and newly re-mastered titles rated G, PG or PG-13 that depict cigarette smoking. • Disney will work with theater owners to encourage the exhibition of an anti-smoking public service announcement before the theatrical exhibition of any of its movies rated G, PG or PG-13 that depicts cigarette smoking. • Disney will include provisions in third-party distribution agreements for movies it distributes that are produced by others in the United States and for which principal photography has not begun at the time the third-party distribution agreement is signed advising filmmakers that it discourages depictions of cigarette smoking in movies that are rated G, PG or PG-13. -

TI£ᄍᆲAL ¬タモ Asynchronous Multiplayer Shooter With

Entertainment Computing 16 (2016) 81–93 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Entertainment Computing journal homepage: ees.elsevier.com/entcom TIṬAL – Asynchronous multiplayer shooter with procedurally generated maps q,qq ⇑ Bhojan Anand , Wong Hong Wei School of Computing, National University of Singapore, Singapore article info abstract Article history: Would it be possible to bring the promise of unlimited re-playability typically reserved for Roguelike Received 1 March 2015 games to competitive multiplayer shooters? This paper tries to address this issue by proposing a novel Revised 21 January 2016 method to dynamically generate maps at run-time almost as soon as players press the Play button, while Accepted 19 February 2016 ensuring the features what players would expect from the genre. The procedures are simple and practi- Available online 7 March 2016 cally feasible to be employed in actual computer games. In addition, the work experiments the possibility of incorporating asynchronous game-play element into a multiplayer shooter with human imitating bots Keywords: where the players can let their bot/avatar replace them when they are not around. The algorithms are Game implemented and evaluated with a playable game. The evaluations prove that playable 3D dynamic maps TIṬAL Prodecural content generation can be generated in order of seconds using game context data to initialise the parameters of the algo- Game map generation rithm. The paper also shows that asynchronous game-play element is a possible feature for consideration Bots in next generation multiplayer shooters. Artificial intelligence Ó 2016 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction 1.1. Procedural content generation This paper demonstrates a novel method for procedurally gen- Procedural Content Generation (PCG) is the use of algorithmic erating dynamic maps at run-time at the click of the ‘Play’ button means to create content [2,3] dynamically during run-time. -

Sample Iis Publication Page

https://doi.org/10.48009/2_iis_2020_185-195 Issues in Information Systems Volume 21, Issue 2, pp. 186-195, 2020 TOWARD A CONCEPTUAL MODEL FOR UNDERSTANDING THE RELATIONSHIPS AMONG MMORPGS, GAMERS, AND ADD-ONS Qiunan Zhang, University of Memphis, [email protected] Yuelin Zhu, University of Memphis, [email protected] Colin G. Onita, San Jose State University, [email protected] M. Shane Banks, University of North Alabama, [email protected] Xihui Zhang, University of North Alabama, [email protected] ABSTRACT The consumption of video games has become a significant economic, cultural, and entertainment phenomenon worldwide. Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Games (MMORPGs) are an important category of such games. In MMORPGs, gamers often play with add-ons to enhance their gaming experience. In previous research studies on MMORPGs, few of them have focused on the relationships among MMORPGs, gamers, and add-ons. This study presents a conceptual framework for use in addressing the following two questions: (1) What is the relationship between gamers and add-ons in MMORPGs? (2) How do factors (such as game quality and updates) impact gamers and add-ons and the relationship between them? In this paper, we develop a research model and describe a quantitative methodology that can be used to test and investigate the above questions. Implications for research and practice, as well as limitations and future research directions, are discussed. Keywords: MMORPGs, Motivations for Gaming, Gamers, Add-ons, Game Quality, Game Updates, Software Platform INTRODUCTION In 2017, video games became the most popular and profitable form of entertainment, producing an estimated revenue of $116 billion eclipsing TV and TV streaming services’ revenue of $105 billion (D’Argenio, 2018). -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

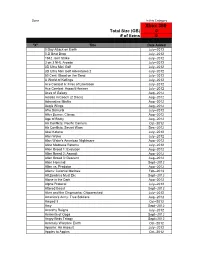

Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of Items 0

Done In this Category Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of items 0 "X" Title Date Added 0 Day Attack on Earth July--2012 0-D Beat Drop July--2012 1942 Joint Strike July--2012 3 on 3 NHL Arcade July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf Adventures 2 July--2012 50 Cent: Blood on the Sand July--2012 A World of Keflings July--2012 Ace Combat 6: Fires of Liberation July--2012 Ace Combat: Assault Horizon July--2012 Aces of Galaxy Aug--2012 Adidas miCoach (2 Discs) Aug--2012 Adrenaline Misfits Aug--2012 Aegis Wings Aug--2012 Afro Samurai July--2012 After Burner: Climax Aug--2012 Age of Booty Aug--2012 Air Conflicts: Pacific Carriers Oct--2012 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars Dec--2012 Akai Katana July--2012 Alan Wake July--2012 Alan Wake's American Nightmare Aug--2012 Alice Madness Returns July--2012 Alien Breed 1: Evolution Aug--2012 Alien Breed 2: Assault Aug--2012 Alien Breed 3: Descent Aug--2012 Alien Hominid Sept--2012 Alien vs. Predator Aug--2012 Aliens: Colonial Marines Feb--2013 All Zombies Must Die Sept--2012 Alone in the Dark Aug--2012 Alpha Protocol July--2012 Altered Beast Sept--2012 Alvin and the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked July--2012 America's Army: True Soldiers Aug--2012 Amped 3 Oct--2012 Amy Sept--2012 Anarchy Reigns July--2012 Ancients of Ooga Sept--2012 Angry Birds Trilogy Sept--2012 Anomaly Warzone Earth Oct--2012 Apache: Air Assault July--2012 Apples to Apples Oct--2012 Aqua Oct--2012 Arcana Heart 3 July--2012 Arcania Gothica July--2012 Are You Smarter that a 5th Grader July--2012 Arkadian Warriors Oct--2012 Arkanoid Live -

Lucasarts and the Design of Successful Adventure Games

LucasArts and the Design of Successful Adventure Games: The True Secret of Monkey Island by Cameron Warren 5056794 for STS 145 Winter 2003 March 18, 2003 2 The history of computer adventure gaming is a long one, dating back to the first visits of Will Crowther to the Mammoth Caves back in the 1960s and 1970s (Jerz). How then did a wannabe pirate with a preposterous name manage to hijack the original computer game genre, starring in some of the most memorable adventures ever to grace the personal computer? Is it the yearning of game players to participate in swashbuckling adventures? The allure of life as a pirate? A craving to be on the high seas? Strangely enough, the Monkey Island series of games by LucasArts satisfies none of these desires; it manages to keep the attention of gamers through an admirable mix of humorous dialogue and inventive puzzles. The strength of this formula has allowed the Monkey Island series, along with the other varied adventure game offerings from LucasArts, to remain a viable alternative in a computer game marketplace increasingly filled with big- budget first-person shooters and real-time strategy games. Indeed, the LucasArts adventure games are the last stronghold of adventure gaming in America. What has allowed LucasArts to create games that continue to be successful in a genre that has floundered so much in recent years? The solution to this problem is found through examining the history of Monkey Island. LucasArts’ secret to success is the combination of tradition and evolution. With each successive title, Monkey Island has made significant strides in technology, while at the same time staying true to a basic gameplay formula. -

A Case Study of the Walt Disney Company Jingwen Yang School of Economics, Hefei University of Technology, Hefei 230601, China [email protected] Abstract

Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, volume 91 1st International Symposium on Economic Development and Management Innovation (EDMI 2019) Analysis of Business Operation Management under the Harvard Analytical Framework: A Case Study of the Walt Disney Company Jingwen Yang School of Economics, Hefei University of Technology, Hefei 230601, China [email protected] Abstract. A comprehensive analysis of financial statements can help its users to understand the production and operation situations and development prospects of enterprises thoroughly and accurately in order to make scientific and rational resolutions. This research employs the Harvard Analytical Framework to analyze the finance and operation management situations of the Walt Disney Company. Development prospects of TWDC are discussed and some suggestions are proposed in this paper. This research is aimed to deepen the understanding and application of financial statement analysis methods. Keywords: Financial analysis; operation management; Harvard Analytical Framework; the Walt Disney Company. 1. Research Background With the constant development of capital market, the diversification of investment entities, and the complexity of investment and financing methods, investment and financing activities become increasingly important for enterprises, but at the same time, they are also led to the increasing uncertainties and risks of business operations. An accurate assessment of business operation and management situations can hardly be conducted without the financial analysis (Yin, 2012). However, Li (2015) finds that the current traditional financial analysis mode solely based on financial statements have its inherent flaws, for today’s market economy is developing rapidly, the market operation is getting mature, the world economic exchanges are becoming more frequent, and the subject and object of financial analysis are increasingly diversified.