TASMANIAN AVIATION HISTORICAL SOCIETY Incorporated the LOG

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Squires Catalogue

Type and Figured Palaeontological Specimens in the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery A CATALOGUE Compiled by Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery Don Squires Hobart, Tasmania Honorary Curator of Palaeontology May, 2012 Type and Figured Palaeontological Specimens in the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery A CATALOGUE Compiled by Don Squires Honorary Curator of Palaeontology cover image: Trigonotreta stokesi Koenig 1825, the !rst described Australian fossil taxon occurs abundantly in its type locality in the Tamar Valley, Tasmania as external and internal moulds. The holotype, a wax cast, is housed at the British Museum (Natural History). (Clarke, 1979) Hobart, Tasmania May, 2012 Contents INTRODUCTION ..........................................1 VERTEBRATE PALAEONTOLOGY ...........122 PISCES .................................................. 122 INVERTEBRATE PALAEONTOLOGY ............9 AMPHIBIA .............................................. 123 NEOGENE ....................................................... 9 REPTILIA [SP?] ....................................... 126 MONOTREMATA .................................... 127 PLEISTOCENE ........................................... 9 MARSUPIALIA ........................................ 127 Gastropoda .......................................... 9 INCERTAE SEDIS ................................... 128 Ostracoda ........................................... 10 DESCRIBED AS A VERTEBRATE, MIOCENE ................................................. 14 PROBABLY A PLANT ............................. 129 bivalvia ............................................... -

3966 Tour Op 4Col

The Tasmanian Advantage natural and cultural features of Tasmania a resource manual aimed at developing knowledge and interpretive skills specific to Tasmania Contents 1 INTRODUCTION The aim of the manual Notesheets & how to use them Interpretation tips & useful references Minimal impact tourism 2 TASMANIA IN BRIEF Location Size Climate Population National parks Tasmania’s Wilderness World Heritage Area (WHA) Marine reserves Regional Forest Agreement (RFA) 4 INTERPRETATION AND TIPS Background What is interpretation? What is the aim of your operation? Principles of interpretation Planning to interpret Conducting your tour Research your content Manage the potential risks Evaluate your tour Commercial operators information 5 NATURAL ADVANTAGE Antarctic connection Geodiversity Marine environment Plant communities Threatened fauna species Mammals Birds Reptiles Freshwater fishes Invertebrates Fire Threats 6 HERITAGE Tasmanian Aboriginal heritage European history Convicts Whaling Pining Mining Coastal fishing Inland fishing History of the parks service History of forestry History of hydro electric power Gordon below Franklin dam controversy 6 WHAT AND WHERE: EAST & NORTHEAST National parks Reserved areas Great short walks Tasmanian trail Snippets of history What’s in a name? 7 WHAT AND WHERE: SOUTH & CENTRAL PLATEAU 8 WHAT AND WHERE: WEST & NORTHWEST 9 REFERENCES Useful references List of notesheets 10 NOTESHEETS: FAUNA Wildlife, Living with wildlife, Caring for nature, Threatened species, Threats 11 NOTESHEETS: PARKS & PLACES Parks & places, -

Deal Island an Historical Overview

Introduction. In June 1840 the Port Officer of Hobart Captain W. Moriarty wrote to the Governor of Van Diemen’s Land, Sir John Franklin suggesting that lighthouses should be erected in Bass Strait. On February 3rd. 1841 Sir John Franklin wrote to Sir George Gipps, Governor of New South Wales seeking his co-operation. Government House, Van Diemen’s Land. 3rd. February 1841 My Dear Sir George. ………………….This matter has occupied much of my attention since my arrival in the Colony, and recent ocurances in Bass Strait have given increased importance to the subject, within the four years of my residence here, two large barques have been entirely wrecked there, a third stranded a brig lost with all her crew, besides two or three colonial schooners, whose passengers and crew shared the same fate, not to mention the recent loss of the Clonmell steamer, the prevalence of strong winds, the uncertainty of either the set or force of the currents, the number of small rocks, islets and shoals, which though they appear on the chart, have but been imperfectly surveyed, combine to render Bass Strait under any circumstances an anxious passage for seamen to enter. The Legislative Council, Votes and Proceedings between 1841 – 42 had much correspondence on the viability of erecting lighthouses in Bass Strait including Deal Island. In 1846 construction of the lightstation began on Deal Island with the lighthouse completed in February 1848. The first keeper William Baudinet, his wife and seven children arriving on the island in March 1848. From 1816 to 1961 about 18 recorded shipwrecks have occurred in the vicinity of Deal Island, with the Bulli (1877) and the Karitane (1921) the most well known of these shipwrecks. -

Don Your Activewear and Walk Your Way Through History in Nsw

Thursday 4 August, 2016 DON YOUR ACTIVEWEAR AND WALK YOUR WAY THROUGH HISTORY IN NSW From tracing the ancient songlines of Indigenous Australians to following in the footsteps of the first convicts sent to our shores, the cooler months of Winter are the perfect time to don your activewear and get walking in NSW. Internationally recognised for its beauty and cultural importance, NSW offers a multitude of walking experiences which showcase the fascinating history and natural beauty of the State. Recent statistics have revealed that the popularity of bushwalking continues to rise, with 7 million visitors travelling to NSW to bushwalk in the year ending March 2016, a growth of 19% on the previous year. With increases recorded in both visitors and visitor nights, NSW continues to attract travellers seeking nature-based tourism experiences. Destination NSW Chief Executive Officer Sandra Chipchase said Regional NSW offers Australia’s most diverse range of bushwalking experiences, with Winter proving the most popular period for domestic daytrip visitors. “As Australia’s most geographically diverse State, NSW is the ideal destination for a walking holiday incorporating UNESCO World Heritage-listed wilderness, Australia’s highest peak or almost 5 million hectares of National Parks and nature reserves,” Ms Chipchase said. Experience a piece of NSW’s history with a walking holiday in Regional NSW, with a few suggestions of fantastic Winter walks in NSW. Convict Tales Follow in the same footsteps as Australia’s convicts by walking part of the UNESCO World Heritage-listed Old Great North Road track in Dharug National Park near Wisemans Ferry. -

6 Must-Stops Along

Travel 2 EDEN Around 33,000 humpback whales travel along the Sapphire Coast during spring every year, and Twofold Bay in Eden has become a favourite resting spot. On the Cat Balou Ocean Discovery Tour you’ll get to see them up close while learning about the history of Eden’s killer whales – including the legendary Old Tom, whose bones can be found at the nearby Eden Killer Whale Museum. 1 PAMBULA The Sapphire Coast is renowned 6 must-stops along the for its fresh oysters, and on Captain Sponge’s Magical Oyster Tour you’ll get to sample them straight from the pristine waters of Pambula Lake as you learn about the local history. Back on dry land, be sure to check out Wheelers Seafood Restaurant and Oyster Farm, where you’ll dine on the freshest seafood, including SAPPHIRE Wheelers’ own Merimbula Lake oysters. And picturesque Pambula Village is the place to go if you want to visit a range of unique and fun boutiques, salons and cafes. COAST! This stunning stretch of the NSW south 6 MERIMBULA coast has something for everyone Let it be said – the Sapphire Coast takes its seafood seriously. At Merimbula Wharf Aquarium & Restaurant you can dine on a sumptuous menu of locally caught seafood and oysters, and head downstairs to the aquarium to catch a glimpse of natural sea life while you’re waiting for your meal! Merimbula is also a popular spot for sailing, kayaking, and stand-up GETTING paddle boarding, and THERE the stunning and For more about Merimbula and the sheltered Bar Beach Sapphire Coast, visit is a perfect Destination NSW at destination for visitnsw.com families. -

Heritage Study Stage 2 2003

THEMATIC HISTORY VOLUME 1 City of Ballarat Heritage Study (Stage 2) April 2003: Thematic History 2 City of Ballarat Heritage Study (Stage 2) April 2003: Thematic History TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS i LIST OF APPENDICES iii CONSULTANTS iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v OVERVIEW vi INTRODUCTION 1 ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING 2 1.TRACING THE EVOLUTION OF THE AUSTRALIAN ENVIRONMENT 2 1.3 Assessing scientifically diverse environments 2 MIGRATING 4 2. PEOPLING AUSTRALIA 4 2.1 Living as Australia's earliest inhabitants 4 2.4 Migrating 4 2.6 Fighting for Land 6 ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT 7 3. DEVELOPING LOCAL, REGIONAL AND NATIONAL ECONOMIES 7 3.3 Surveying the continent 7 3.4 Utilising natural resources 9 3.5 Developing primary industry 11 3.7 Establishing communications 13 3.8 Moving goods and people 14 3.11 Altering the environment 17 3.14 Developing an Australian engineering and construction industry 19 SETTLING 22 4. BUILDING SETTLEMENTS, TOWNS AND CITIES 22 4.1 Planning urban settlements 22 4.3 Developing institutions 24 LABOUR AND EMPLOYMENT 26 5. WORKING 26 5.1 Working in harsh conditions 26 EDUCATION AND FACILITIES 28 6. EDUCATING 28 6.1 Forming associations, libraries and institutes for self-education 28 6.2 Establishing schools 29 GOVERNMENT 32 i City of Ballarat Heritage Study (Stage 2) April 2003: Thematic History 7. GOVERNING 32 7.2 Developing institutions of self-government and democracy 32 CULTURE AND RECREATION ACTIVITIES 34 8. DEVELOPING AUSTRALIA’S CULTURAL LIFE 34 8.1 Organising recreation 34 8.4 Eating and Drinking 36 8.5 Forming Associations 37 8.6 Worshipping 37 8.8 Remembering the fallen 39 8.9 Commemorating significant events 40 8.10 Pursuing excellence in the arts and sciences 40 8.11 Making Australian folklore 42 LIFE MATTERS 43 9. -

Print Cruise Information

Treasures of the South Australian coast and Tasmania From 12/16/2022 From Sydney Ship: LE LAPEROUSE to 12/23/2022 to Hobart, Tasmania Join us aboard Le Lapérouse for a wonderful new 8-day expedition cruise from Sydney to Hobart, to discover thenatural and cultural treasures of the south-eastern coast of Australia and Tasmania. After sailing out of Sydney and its beautiful harbour, you will set a course for the Jervis Bay area, in New South Wales. Renowned for its white-sand beaches bathed in turquoise water, this dynamic and creative region with a rich biodiversity is also a popular refuge for many birds. Next on your itinerary, Eden on the New South Wales South coast will reveal its long-associated history with whales and let you explore the region's stunning National Parks and scenic coastline. Reaching Maria Island in Tasmania, discover the region's history and extraordinary wildlife sanctuaries alongside your team of expedition experts. On the Tasman Peninsula, navigate the rugged coastline and spot the various local marine life including Australian Fur Seals, little penguins and whales, as well as explore the beautiful inland woodland and forests. Your voyage will end in Hobart, Australia's second oldest capital, your port of disembarkation. The information in this document is valid as of 9/25/2021 Treasures of the South Australian coast and Tasmania YOUR STOPOVERS : SYDNEY Embarkation 12/16/2022 from 4:00 PM to 5:00 PM Departure 12/16/2022 at 6:00 PM Nestled around one of the world’s most beautiful harbours,Sydney is both trendy and classic, urbane yet laid-back. -

ECM 2046783 V13 List of Names of Streets/Roads, Suburbs, Parks

CITY OF BELMONT List of Names of Streets/Roads, Suburbs, Parks, Perth Airport Roads and Schools Prepared by the City of Belmont Tel: (08) 9477 7222 Fax: (08) 9478 1473 Email: [email protected] Website: www.belmont.wa.gov.au Date: 04/07/19 Document Set ID: 2046783 Version: 13, Version Date: 04/07/2019 Date 17/10/2014 Table of Contents Contents 1. CITY OF BELMONT POLICY MANUAL........................................................................1 2. WORKING COPY OF SCHEDULE OF NAMES RESERVED FOR STREETS (ROAD NAMES) AND PARKS ..............................................................................................2 3. LIST OF CURRENT STREET NAMES (ROAD NAMES) WITHIN THE CITY OF BELMONT............................................................................................................11 4. LIST OF FORMER STREET NAMES (ROAD NAMES) (NO LONGER IN EXISTENCE / DUPLICATION ETC)...............................................................................................38 5. SUBURB NAMES IN THE CITY OF BELMONT ............................................................41 6. LIST OF CURRENT STREET NAMES (ROAD NAMES) WITHIN PERTH AIRPORT AREA..................................................................................................................43 7. LIST OF FORMER PERTH AIRPORT STREET NAMES (ROAD NAMES) (NO LONGER IN EXISTENCE).....................................................................................................87 8. PARK NAMES IN THE CITY OF BELMONT ................................................................91 -

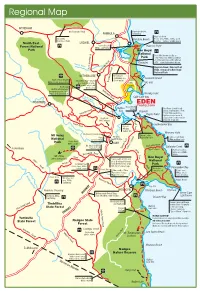

Regional Map

Regional Map WYNDHAM Mt Darragh Road Barmouth Beach PAMBULA Swimming Haycock Point Goodenia Pambula Beach Picnic area, BBQs, toilets, good Rainforest Walk beaches – fishing, SCUBA diving South East LOCHIEL Severs Beach Haycock Point Forest National BBQs, swimming Park Ben Boyd National Red cliffs (known locally as Park “The Pinnacles) Striking contrast of white sandstone cliffs with red cliffs – a photoghraphers dream Yowaka River Pinnacles Haycock Road, 8km north of Back Creek Road Eden, entrance to Ben Boyd Nethercote Road National Park NETHERCOTE Broadwater swimming area Leonards Island Nullica River Mouth Quarantine Bay – 4 lane (fresh water) Broadwater Road BBQs, picnic area, toilets boat launching ramp, Lake 4WD ONLY ONLY public wharf and Curalo Boydtown picnic area Built by whaling king Nethercote Road Benjamin Boyd in 1843 Ruins of Boyds Church Worang Point Nullica River Calle Calle Bay TOWAMBA EDEN TWOFOLD BAY Nullica Navy Wharf fishingTWOFOLD BAY Red Point (South Head) Bay Chipmill Boyds Tower built in 1846 Towamba Road 19.5m high sandstone Boyds Tower lighthouse was never lit, Boydtown steps down to observation platform down cliff Hill Cottages Boyd Snake Track Road Leatherjacket Bay Towamba River Historic Whaling station site Mowarry Point Kiah Country Gardens Mt Imlay Edrom Lodge Kiah Whelans Built 1910-1913 Light to Light Walk National General Store Swamp Bridge 30km walking track Park Picnic Area BBQs, water KIAH Mt. Imlay walking Duck Hole Road Saltwater Creek Edrom Road To Bombala track turn off 15km to Chipmiill Green GRAVEL ROAD Fishing, beaches, Road picnic area, BBQs, Burrawang Cape toilets Mt. Imlay Road Ben Boyd Imlay Road 886m walking track 19km south of Eden turn off to Ben Boyd National National Anteater Park, Boyds Tower, Chip Scrubby Creek Road Park Picnic Area, BBQs, Mill, Edrom, Greencape Wonboyn Bittangabee Bay toilets, water Picnic Area 23km south of Eden Lake Resort Picnic area, Turn off to Nadgee BBQs, toilets, Wallagaruagh River Nature Reserve ruins, beaches Picnic Area Mt. -

Prospects and Challenges for the Hunter Region a Strategic Economic Study

Prospects and challenges for the Hunter region A strategic economic study Regional Development Australia Hunter March 2013 Liability limited by a scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation. © 2013 Deloitte Access Economics Pty Ltd Prospects and challenges for the Hunter region Contents Executive summary .................................................................................................................... i 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1 Part I: The current and future shape of the Hunter economy .................................................... 3 2 The Hunter economy in 2012 .......................................................................................... 4 2.2 Population and demographics ........................................................................................... 5 2.3 Workforce and employment ............................................................................................. 8 2.4 Industrial composition .................................................................................................... 11 3 Longer term factors and implications ............................................................................ 13 3.1 New patterns in the global economy ............................................................................... 13 3.2 Demographic change ...................................................................................................... 19 -

Severe Storms on the East Coast of Australia 1770–2008

SEVERE STORMS ON THE EAST COAST OF AUSTRALIA 1770 – 2008 Jeff Callaghan Research Fellow, Griffith Centre for Coastal Management, Griffith University, Gold Coast, Qld Formerly Head Severe Storm Forecaster, Bureau of Meteorology, Brisbane Dr Peter Helman Senior Research Fellow, Griffith Centre for Coastal Management, Griffith University, Gold Coast, Qld Published by Griffith Centre for Coastal Management, Griffith University, Gold Coast, Queensland 10 November 2008 This publication is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. ISBN: 978-1-921291-50-0 Foreword Severe storms can cause dramatic changes to the coast and devastation to our settlements. If we look back through history, to the first European observations by James Cook and Joseph Banks on Endeavour in 1770, we can improve our understanding of the nature of storms and indeed climate on the east coast. In times of climate change, it is essential that we understand natural climate variability that occurs in Australia. Looking back as far as we can is essential to understand how climate is likely to behave in the future. Studying coastal climate through this chronology is one element of the process. Analysis of the records has already given an indication that east coast climate fluctuates between phases of storminess and drought that can last for decades. Although records are fragmentary and not suitable for statistical analysis, patterns and climate theory can be derived. The dependence on shipping for transport and goods since European settlement ensures a good source of information on storms that gradually improves over time. -

Alphabetical Table Of

TASMANIAN ACTS AND STATUTORY RULES TASMANIAN ACTS N – R AND STATUTORY RULES Nation Building and Jobs Plan Facilitation (Tasmania) Act 2009, No. 5 of 2009 (commenced 27 April 2009) Last consolidation: 31 December 2012 (includes changes under the Legislation Publication Act 1996 in force as at 31 December 2012) Amendments commenced in 2009 – 2016: Nation Building and Jobs Plan Facilitation (Tasmania) Act 2009, No. 5 of 2009 (commenced 31 December 2012) – the Act, except Pt. 1 (ss. 1-4) and s. 18 expired 31 December 2012 unless earlier by notice made by the Treasurer National Broadband Network (Tasmania) Act 2010, No. 48 of 2010 (commenced 21 December 2010) Last consolidation: 16 August 2017 (up to and including amendment by the Aboriginal Relics (Consequential Amendments) Act 2017 and changes under the Legislation Publication Act 1996 in force as at 16 August 2017) Amendments commenced in 2017: Building (Consequential Amendments) Act 2016, No. 12 of 2016 (commenced 1 January 2017) – amended s. 28(c) Aboriginal Relics (Consequential Amendments) Act 2017, No. 17 of 2017 (commenced 16 August 2017) – amended s. 28 National Energy Retail Law (Tasmania) Act 2012, No. 11 of 2012 (commenced 1 July 2012, see S.R. 2012, No. 49) Last consolidation: 1 June 2013 (up to and including amendment by the Electricity Reform (Implementation) Act 2013 and changes under the Legislation Publication Act 1996 in force as at 1 June 2013) Amendments commenced in 2012 – 2016: Electricity Reform (Implementation) Act 2013, No. 5 of 2013 (commenced 1 June 2013) – amended ss. 15 and 18; inserted 17A Regulations: National Energy Retail Law (Tasmania) Regulations 2012 (2012/51 amended by 2013/27) National Energy Retail Law (Tasmania) s.