The Maudsley Hospital: Design and Strategic Direction, 1923–1939

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapother House & Michael Rutter Centre, Maudsley Hospital

Mapother House & Michael Rutter Centre, Maudsley Hospital (Reference: 20/AP/2768) This document provides an overview of the South London and Maudsley NHS Trust’s (SLaM) application for the redevelopment of Mapother House, Michael Rutter Centre and the Professorial Building. The application seeks to deliver new homes and enable the transformation of our inpatient facilities to create buildings fit to deliver world class mental health care in the 21st century - modernised, high quality, inpatient and community facilities serving communities in Southwark and Lambeth, as well as a centre for national excellence. Background South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust SLaM provides the widest range of NHS mental health services in the UK. We aim to make a difference to lives by seeking excellence in all areas of mental health and wellbeing. Our 4,800 staff serve a local population of 1.3 million people. We offer more than 230 services including inpatient wards, outpatient and community services. We provide inpatient care for approximately 3,900 people each year and we treat more than 67,000 patients in Lambeth, Southwark, Lewisham and Croydon. We also provide more than 50 specialist services for children and adults across the UK including perinatal services, eating disorders, psychosis and autism. Masterplan South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM) and its partners are investing £140 million in modern mental healthcare services and facilities at our Maudsley Hospital site, providing better care and experience for local people. The upgrades to the site have formed a Masterplan, which includes three initial phases (1A-C): • 1A: Transforming Douglas Bennett House into a modern inpatient facility with eight co-designed adult wards. -

Kjl MSATCALLS on HAWAI ARMY

Kamehameha irrsrlT 3:30 Pay Races 3fS TTrrvv nirffmr and Polo Editio 1 vn- 1 . PHR K FIVK KNTS i r.;r iiDNorri-i'- . tkkritoi.y or ii.wn. Trft A i iA yjj ww v Jl TCALLS ON HAWAI ARMY MEN (G k MSA ffiY OFFICERS M WAIIANS IN GREA T OUTPOURING PA Y TRIBUTE POSSIBLE SERVICE IN FRANCE TO MEMORY OF BELOVED RULER,. KAMEHAMEHA Oil PERMIT'S OR COMMAND ON MAINLAND IS STAFF IN PARIS IN SATURDAY NIGHT CABLEGRAM to Lord Northciiffe Comes LGEN. strong ordered to report to . war depart to Represent British America ment EVERY OFFICER WHO CAN BE SPARED FOR DUTY Mission; King George Honors In states ITIilllCU -- -- - U. O. J i w. ... -- C; a.," - The Associated Press ,"at Every army officer in the Hawaiian department who can been by - up , the be spared for duty in the United States has called the coon- today summed " r i day's events in the war zones t war department, the call to take effect at the earliest possi- as follows:. r, ble date. "The .British today, fought In a cablegram received Saturday evening, Brig. -- Gen. forward to a decided advance Frederick S. Strong, commanding the Hawaiian department, ' - - k, south of Messines and have re IV! , s ? was ordered to report as soon as possible the names of local sumed their strong ,l trench officers who are not imperatively needed for service in Hawaii 70-ini- ' v v le : ' big- "'tf. ; J ' I ' This Is regarded one of the raids along a front. - : v. .;,. " hv." r is Jiaye; launched gest orders that has been received at The Italians . -

Appointment Brief Chief Operating Officer August 2020

Appointment brief Chief Operating Officer August 2020 Introduction South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM) is an exceptional organisation. Everything we do as a Trust is to support people to recover from mental illness and to help them improve their lives. Benefitting from world-class research and innovation, award-winning services and a world-renowned brand, we are uniquely placed to provide the best possible services to our local communities and beyond. Our biggest asset is our passionate and highly skilled workforce, who are dedicated to providing the best quality care to the people who use our services, often in difficult circumstances. We have managed the many challenges that COVID-19 has presented with great success and this has only been possible through the hard work and commitment of our staff. We are pleased with our internal patient experience survey results, where 96% of respondents said they found staff kind and caring and 87% of respondents to the NHS Friends and Families Test said that they would recommend the Trust to their friends and families based on their experience of the services provided. Operating across more than 90 sites, including Bethlem Royal Hospital and Maudsley Hospital, we provide a staggering range of services, ranging from core mental health services to our local boroughs, and more than 50 specialist mental health services across the UK. We are rated ‘Good’ overall by the Care Quality Commission, including for the ‘Well Led’ domain. With our strong commitment to working in partnership with our service users, carers and local communities, and to quality improvement, we believe we are capable of delivering truly outstanding services across all our teams We know that we will only achieve this if SLaM truly is a great place to work, where all our staff feel valued, developed and supported. -

Annual Report and Financial Statements 2019 / 2020 the Maudsley Charity Is the Largest NHS Mental Health Charity in the United Kingdom

Annual Report and Financial Statements 2019 / 2020 The Maudsley Charity is the largest NHS mental health charity in the United Kingdom We back better mental health by working together with our partners, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM) and King’s College London (KCL), two world-leading organisations, to deliver a vision that is genuinely enabling us to improve the lives of people with mental illness. Kairos Community Trust, a Maudsley Charity funded Community and Connection project. Mental Health In 2018 This means more than A snapshot of mental health in the UK provided there were 16 people per day took by the Mental Health Foundation their life 6,154 It is estimated that suicides in 10-25 times that number Great Britain. attempt suicide The UK has one of the highest 1 in 4 people experience self-harm rates mental health issues each year in Europe 1.25 million people in the UK have an eating disorder (1 in 50) and more than 1 in 7 young women(1) 30-50% Every year mental ill health costs the UK economy an of people 24% of women estimated £70bn in lost productivity at work, benefit with a severe and 13% of men payments and health care expenditure. That is more than mental illness double the cost of cancer, heart disease and stroke combined(2) also have in England are diagnosed with problems with depression in their lifetime substance use Source: Mental Health Foundation: https://mhfaengland.org/mhfa-centre/research-and-evaluation/mental-health-statistics/ (1) Micali, N. et al “The incidence of eating disorders in the -

Junior Clinical Fellow in Neurosciences GRADE

JOB SPECIFICATION JOB TITLE: Junior Clinical Fellow in Neurosciences GRADE: Junior Clinical Fellow HOURS: 40 plus on call RESPONSIBLE TO: Clinical Lead ACCOUNTABLE TO: Clinical Director - Neurosciences TENURE: 6 months Background King’s College Hospital King’s College Hospital is one of the largest and busiest in London, with a well-established national and international reputation for clinical excellence, innovation and achievement. Our Trust is located on multiple sites serving the economically diverse boroughs of Southwark, Lambeth and Bromley and Bexley. As a major employer with over 10,500 staff we play an important part in helping reduce local, social and health inequalities. The Trust provides a broad range of secondary services, including specialist emergency medicine (e.g. trauma, cardiac and stroke). It works in close collaboration with other health providers in South East London, including CCGs to ensure the sustainability and excellence of services across the area. In recent years, there has been substantial investment in both the facilities and resources of the hospital, which has transformed the quality of care that it now delivers. It also provides a number of leading edge tertiary services, such as liver transplantation, neurosciences, haemato-oncology, foetal medicine, cardiology and cardiac surgery, on a regional and national basis. King’s College Hospital has an enviable track record in research and development and service innovation. In partnership with King’s College London the Trust has recently been awarded a National Research Centre in Patient Safety and Service Quality. It is also a partner in two National Institute for Health Research biomedical research centres. The first is a Comprehensive centre with King’s College London and Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and the second is a Specialist centre with the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and the Institute of Psychiatry. -

Records of Patients in London Hospitals

RESEARCH GUIDE 35 - Records of Patients in London Hospitals CONTENTS Introduction Hospital Archives Guides to Hospital Records Lying In Hospitals Access to Patients Records Other sources of information about hospital patients Registers of patients in psychiatric hospitals Introduction Many of the monastic hospitals which had cared for the sick poor of medieval London were suppressed on the dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s and 1540s. St. Bartholomew's Hospital, St. Thomas' Hospital, and Bethlem Royal Hospital were saved by the City of London Corporation, which obtained grants of the hospitals and their endowments from King Henry VIII and from his son, Edward VI. The hospitals were refounded as secular institutions, St. Bartholomew's and St. Thomas' caring for the physically sick and Bethlem for the insane. Over time they established their virtual independence from the City of London. Thomas Guy, a London publisher and bookseller, left the fortune which he made out of the South Sea Bubble, to found Guy's Hospital which opened in 1725. Other major London hospitals, including the Westminster, Royal London, Middlesex, and St. George's Hospitals, were established in the 18th century on the voluntary principle. Medical men gave their services free while wealthy subscribers gave money each year to support the hospitals, in return for which they gained a share in the government of the hospital and the right to nominate patients. Medical schools developed in association with the hospitals. Many categories of the sick, including pregnant women, the mentally ill, and patients suffering from incurable or infectious diseases were excluded from most hospitals. -

CIA), Oct 1997-Jan 1999

Description of document: FOIA Request Log for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), Oct 1997-Jan 1999 Requested date: 2012 Released date: 2012 Posted date: 08-October-2018 Source of document: FOIA Request Information and Privacy Coordinator Central Intelligence Agency Washington, DC 20505 Fax: 703-613-3007 FOIA Records Request Online The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 1998 Case Log Creation Date Case Number Case Subject 07-0ct-97 F-1997-02319 FOIA REQUEST VIETNAM CONFLICT ERA 1961 07-0ct-97 F-1997-02320 FOIA REQUEST PROFESSOR ZELLIG S. HARRIS FOIA REQUEST FOR MEETING MINUTES OF THE PUBLIC DISCLOSURE COORDINATING COMMITTEE 07-0ct-97 F-1997-02321 (PDCC) 07-0ct-97 F-1997-02322 FOIA REQUEST RE OSS REPORTS AND PAPERS BETWEEN ALLEN DULLES AND MARY BANCROFT 07-0ct-97 F-1997-02323 FOIA REQUEST CIA FOIA GUIDES AND INDEX TO CIA INFORMATION SYSTEMS 07-0ct-97 F-1997-02324 FOIA REQUEST FOR INFO ON SELF 07-0ct-97 F-1997-02325 FOIA REQUEST ON RAOUL WALLENBERG 07-0ct-97 F-1997-02326 FOIA REQUEST RE RAYMOND L. -

Psychiatry in Descent: Darwin and the Brownes Tom Walmsley Psychiatric Bulletin 1993, 17:748-751

Psychiatry in descent: Darwin and the Brownes Tom Walmsley Psychiatric Bulletin 1993, 17:748-751. Access the most recent version at DOI: 10.1192/pb.17.12.748 References This article cites 0 articles, 0 of which you can access for free at: http://pb.rcpsych.org/content/17/12/748.citation#BIBL Reprints/ To obtain reprints or permission to reproduce material from this paper, please write permissions to [email protected] You can respond http://pb.rcpsych.org/cgi/eletter-submit/17/12/748 to this article at Downloaded http://pb.rcpsych.org/ on November 25, 2013 from Published by The Royal College of Psychiatrists To subscribe to The Psychiatrist go to: http://pb.rcpsych.org/site/subscriptions/ Psychiatrie Bulle!in ( 1993), 17, 748-751 Psychiatry in descent: Darwin and the Brownes TOMWALMSLEY,Consultant Psychiatrist, Knowle Hospital, Fareham PO 17 5NA Charles Darwin (1809-1882) enjoys an uneasy pos Following this confident characterisation of the ition in the history of psychiatry. In general terms, Darwinian view of insanity, it comes as a disappoint he showed a personal interest in the plight of the ment that Showalter fails to provide any quotations mentally ill and an astute empathy for psychiatric from his work; only one reference to his many publi patients. On the other hand, he has generated deroga cations in a bibliography running to 12pages; and, in tory views of insanity, especially through the writings her general index, only five references to Darwin, all of English social philosophers like Herbert Spencer of them to secondary usages. (Interestingly, the last and Samuel Butler, the Italian School of "criminal of these, on page 225, cites Darwin as part of anthropology" and French alienists including Victor R. -

Philosophy of Mind & Psychology Reading Group

NB: This is an author’s version of the paper published in Med Health Care and Philos (2014) 17:143–154. DOI 10.1007/s11019-013-9519-8. The final publication is available at Springer via http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11019-013-9519-8 This version may differ slightly from the published version and has different pagination. On deciding to have a lobotomy: either lobotomies were justified or decisions under risk should not always seek to Maximise Expected Utility. Rachel Cooper Abstract In the 1940s and 1950s thousands of lobotomies were performed on people with mental disorders. These operations were known to be dangerous, but thought to offer great hope. Nowadays, the lobotomies of the 1940s and 1950s are widely condemned. The consensus is that the practitioners who employed them were, at best, misguided enthusiasts, or, at worst, evil. In this paper I employ standard decision theory to understand and assess shifts in the evaluation of lobotomy. Textbooks of medical decision making generally recommend that decisions under risk are made so as to maximise expected utility (MEU) I show that using this procedure suggests that the 1940s and 1950s practice of psychosurgery was justifiable. In making sense of this finding we have a choice: Either we can accept that psychosurgery was justified, in which case condemnation of the lobotomists is misplaced. Or, we can conclude that the use of formal decision procedures, such as MEU, is problematic. Keywords Decision theory _ Lobotomy _ Psychosurgery _ Risk _ Uncertainty 1. Introduction In the 1940s and 1950s thousands of lobotomies – operations designed to destroy portions of the frontal lobes – were performed on mentally ill people. -

The Maudsley Hospital: Design and Strategic Direction, 1923–1939

Medical History, 2007, 51: 357–378 The Maudsley Hospital: Design and Strategic Direction, 1923–1939 EDGAR JONES, SHAHINA RAHMAN and ROBIN WOOLVEN* Introduction The Maudsley Hospital officially opened in January 1923 with the stated aim of finding effective treatments for neuroses, mild forms of psychosis and dependency disorders. Significantly, Edward Mapother, the first medical superintendent, did not lay a claim to address major mental illness or chronic disorders. These objectives stood in contrast to the more ambitious agenda drafted in 1907 by Henry Maudsley, a psychiatrist, and Frederick Mott, a neuropathologist.1 While Mapother, Maudsley and Mott may have disagreed about the tactics of advancing mental science, they were united in their con- demnation of the existing asylum system. The all-embracing Lunacy Act of 1890 had so restricted the design and operation of the county asylums that increasing numbers of reformist doctors sought to circumvent its prescriptions for the treatment of the mentally ill. Although the Maudsley began to treat Londoners suffering from mental illness in 1923, it had an earlier existence first as a War Office clearing hospital for soldiers diagnosed with shell shock,2 and from August 1919 to October 1920 when funded by the Ministry of Pensions to treat ex-servicemen suffering from neurasthenia. Both Mott, as director of the Central Pathological Laboratory and the various teaching courses, and Mapother had executive roles during these earlier incarnations. These important clinical experiences informed the aims and management plan that they drafted for the hospital once it had returned to the London County Council’s (LCC) control. On the surface, the Maudsley could not have been further from the traditional asylum. -

PSYCHIATRIC HOSPITALS in the UK in the 1960S

PSYCHIATRIC HOSPITALS IN THE UK IN THE 1960s Witness Seminar 11 October 2019 Claire Hilton and Tom Stephenson, convenors and editors 1 © Royal College of Psychiatrists 2020 This witness seminar transcript is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. Please cite this source as: Claire Hilton and Tom Stephenson (eds.), Psychiatric Hospitals in the UK in the 1960s (Witness Seminar). London: RCPsych, 2020. Contents Abbreviations 3 List of illustrations 4 Introduction 5 Transcript Welcome and introduction: Claire Hilton and Wendy Burn 7 Atmosphere and first impressions: Geraldine Pratten and David Jolley 8 A patient’s perspective: Peter Campbell 16 Admission and discharge: 20 Suzanne Curran: a psychiatric social work perspective Professor Sir David Goldberg: The Mental Health Act 1959 (and other matters) Acute psychiatric wards: Malcolm Campbell and Peter Nolan 25 The Maudsley and its relationship with other psychiatric hospitals: Tony Isaacs and Peter Tyrer 29 “Back” wards: Jennifer Lowe and John Jenkins 34 New roles and treatments: Dora Black and John Hall 39 A woman doctor in the psychiatric hospital: Angela Rouncefield 47 Leadership and change: John Bradley and Bill Boyd 49 Discussion 56 The contributors: affiliations and biographical details -

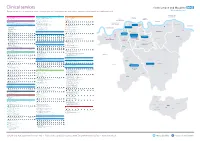

Everything We Do Is to Improve the Lives of the People and Communities We Serve and to Promote Mental Health and Wellbeing for All

Clinical services Everything we do is to improve the lives of the people and communities we serve and to promote mental health and wellbeing for all No. Borough Clinical Academic Group No. Borough Clinical Academic Group No. Borough Clinical Academic Group Bexley Lambeth Southwark 1 Drug and Alcohol Service (Bexley) - 01322 357 940 Addictions 29 Psychosis Promoting Recovery (Lambeth South) - 020 3228 8100 Psychosis 55 Drug and Alcohol Service (Southwark) - 020 3228 9400 Addictions Drug Intervention Programme (Bexley) - 01322 357 940 South Asian Community Mental Health Service (Lambeth) - 020 3228 8100 151 Blackfriars Road, London SE1 8EL Erith Health Centre, 50 Pier Road, Erith DA8 1AT 380 Streatham High Road, London SW16 6HP Southwark Erith Streatham 56 Smoking Service - 020 3228 3848 30 Placements Assessments Monitoring Services - 020 3228 7000 Marina House, 63-65 Denmark Hill, London SE5 8RS Bromley Social Inclusion, Hope and Recovery Project (Lambeth) - 020 3228 7050 Denmark Hill 308 - 312 Brixton Road, London SW9 6AA 2 Bethlem Royal Hospital 57 Forensic Community Service (Southwark) - 020 3228 7168 Behavioural and Monks Orchard Road, Beckenham BR3 3BX Brixton Chaucer Resource Centre, 13 Ann Moss Way, London SE16 2TH Developmental Psychiatry 31 Psychosis Promoting Recovery (Lambeth Central) - 020 3228 6940 Eden Park West Wickham Bromley South then bus 119 East Croydon then bus 119, 194 or 198. Canada Water Surrey Quays Psychosis Promoting Recovery (Lambeth North East) - 020 3228 6940 A bus service runs between Bethlem and Maudsley