How the Forward Pass Killed Joe Hall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Residents Hammer Board on Stub out Sugarmill Homeowners Urge Commissioners BOCC Orders Gov’T Center Appraisal

Chronicle coupon night: $2 off fair midway armband /C3 WEDNESDAY TODAY CITRUS COUNTY & next morning HIGH 61 Mostly sunny and LOW cool. PAGE A4 43 www.chronicleonline.com MARCH 26, 2014 Florida’s Best Community Newspaper Serving Florida’s Best Community 50¢ VOL. 119 ISSUE 231 Residents hammer board on stub out Sugarmill homeowners urge commissioners BOCC orders gov’t center appraisal to vote against developer’s residential projects CHRIS VAN ORMER mation to make a decision about the Staff writer purchase. MIKE WRIGHT chambers in hopes of persuading com- Two commissioners who voted “no” Staff writer missioners to oppose developer INVERNESS — Three county com- supported continuing to lease the of- Nachum Kalka’s request to pave a missioners pushed the idea forward on fice space for the remaining seven INVERNESS — Sugarmill Woods res- 213-foot chunk of vacant land known as Tuesday to buy the building that years of the county’s 10-year lease idents descended on the courthouse to the Oak Village Boulevard stub out. houses the West Citrus Government agreement instead. let county commissioners know in ab- Residents who live in Oak Village, the Center. Commissioner Dennis Damato was solute certain terms what they think of a Sugarmill community bordering the By a 3-2 vote, the Citrus County strongly in favor of pursuing the due developer’s plan to use their quiet road Hernando County line, say Kalka wants Board of County Commissioners in- diligence research process staff began for his residential projects. the stub out paved so he can connect the structed county staff to provide formal They don’t like it. -

LEAGUE HOCKEY for Hester SILVER SPRAY

1 lf l i ,,n 1,1 fi •,Yrrw"v *1 >" v i i v IPXGESK <THE LETHBRIDGE DAILY HERALD THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 112,1925 LEAGUE HOCKEY FOR BILLY • • • • • • • • • ^ • • • • • • EVANS SAYS Pres. Cheeseman Of Baseball Body V BABE REFORMS Now that Babe Ruth has decided t longer to be "Boob" Ruth to the tout • . • bookmakers and confidence men, • MARANVILLE SLATED « •> might bo weir to get a'couple of dth( Macleod Given Berth ANOTHER FROM THE OLD SOD FOR ANOTHER BERTH • incidents'ont bt our system relative" the wild days' of tho Bambino. • • • * * « • • * "Rabbit" Maranvillo is almost Well do I recall a certain afternoc Lucien ,.Vinez, European Lightweight Champion certain'to be; traded by theChl- in New York when Babe's plea ot sic cago Cubs before tho opening OF jness', didn't; ge£ over with Matagj Intermediate Hockey, of next season. Maranville, Hugglns. It happened one of the b: having had a whirl as man running races was carded at Belmoi ager and. failed, won't be of BASEBALL FROM that day. any great help to the new club Before the game Babe had laid pilot. It is rumored that the, heavy wager on ono of tho'entries - Annual Alta. Parley "Rabbit" will go to Cincinnati. the first, race. Just as the game star! ed someone confided' to him that hi AMATEUTBODY selection wa,s tin also. ran. The btl was for something like $1000, | Ladies Hockey Given Official ; FalltfVe In the first race merely ii WOMEN TAKE TO A. A. B. A. Head States Posi creased Ruth's desire to get to tli Recognition at Calgary "Y" WATER SPORTS • race track. -

Canada, Hockey and the First World War JJ Wilson

This article was downloaded by: [Canadian Research Knowledge Network] On: 9 September 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 783016864] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK International Journal of the History of Sport Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713672545 Skating to Armageddon: Canada, Hockey and the First World War JJ Wilson To cite this Article Wilson, JJ(2005) 'Skating to Armageddon: Canada, Hockey and the First World War', International Journal of the History of Sport, 22: 3, 315 — 343 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/09523360500048746 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523360500048746 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

1934 SC Playoff Summaries

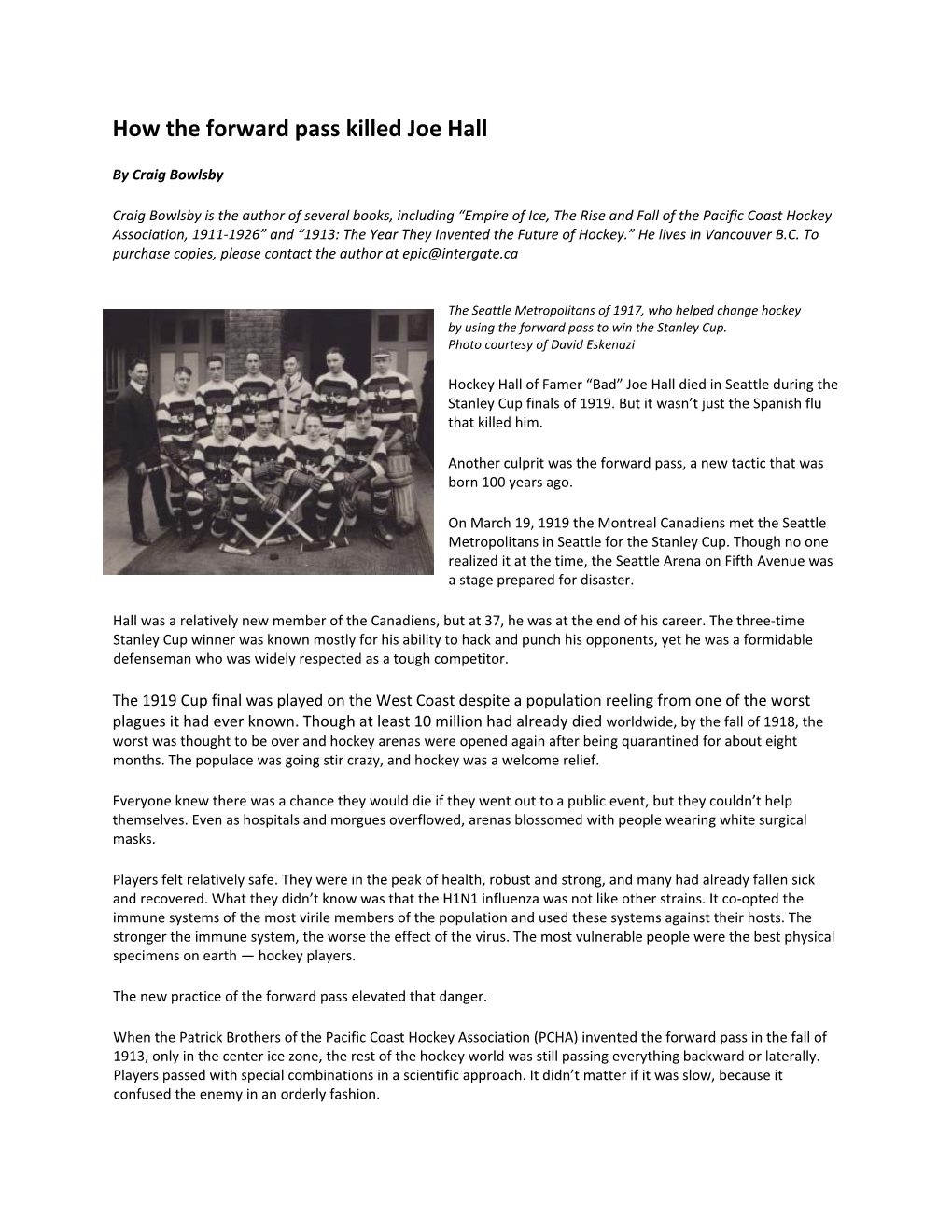

TORONTO ST. PATRICKS STANLEY CUP CHAMPIONS 192 2 Lloyd Andrews, Harry Cameron, Corb Denneny, Cecil “Babe” Dye, Eddie Gerard BORROWED FOR G4 OF SCF FROM OTTAWA, Stan Jackson, Ivan Mitchell, Reg Noble CAPTAIN, Ken Randall, John Ross Roach, Rod Smylie, Ted Stackhouse, Billy Stuart Charlie Querrie MANAGER George O’Donoghue HEAD COACH 1922 NHL FINAL OTTAWA SENATORS 30 v. TORONTO ST. PATRICKS 27 GM TOMMY GORMAN, HC PETE GREEN v. GM CHARLIE QUERRIE, HC GEORGE O’DONOGHUE ST. PATRICKS WIN SERIES 5 GOALS TO 4 Saturday, March 11 Monday, March 13 OTTAWA 4 @ TORONTO 5 TORONTO 0 @ OTTAWA 0 FIRST PERIOD FIRST PERIOD 1. TORONTO, Ken Randall 0:30 NO SCORING 2. TORONTO, Billy Stuart 2:05 3. OTTAWA, Frank Nighbor 6:05 SECOND PERIOD 4. OTTAWA, Cy Denneny 7:05 NO SCORING 5. OTTAWA, Cy Denneny 11:00 THIRD PERIOD SECOND PERIOD NO SCORING 6. TORONTO, Babe Dye 3:50 7. OTTAWA, Frank Nighbor 6:20 Game Penalties — Cameron T 3, Corb Denneny T, Clancy O, Gerard O, Noble T, F. Boucher O 2, Smylie T 8. TORONTO, Babe Dye 6:50 GOALTENDERS — SENATORS, Clint Benedict; ST. PATRICKS, John Ross Roach THIRD PERIOD 9. TORONTO, Corb Denneny 15:00 GWG Officials: Cooper Smeaton At The Arena, Ottawa Game Penalties — Broadbent O 3, Noble T 3, Randall T 2, Dye T, Nighbor O, Cameron T, Cy Denneny O, Gerard O GOALTENDERS — SENATORS, Clint Benedict; ST. PATRICKS, John Ross Roach Official: Cooper Smeaton 8 000 at Arena Gardens © Steve Lansky 2014 bigmouthsports.com NHL and the word mark and image of the Stanley Cup are registered trademarks and the NHL Shield and NHL Conference logos are trademarks of the National Hockey League. -

The 1919 Stanley Cup Finals

The 1919 Stanley Cup Finals Seattle hockey fans were looking forward to the 1919 Stanley Cup Finals. The hometown Metropolitans were coming off of a solid second place finish and a playoff series win over Vancouver, earning the right to host the Montreal Canadiens in a rematch of the 1917 finals. As the fans filed into the Arena on March 19 expectations were high for a good, competitive series. Little did anyone know what an incredible physical toll the series would take on the players over the upcoming 12 days, culminating with the unfortunate death of Joe Hall of the Canadiens. The series started innocently enough as the Mets took advantage of a tired Montreal squad that had just arrived in town, winning the opener by a score of 7-0. Muzz Murray of the Mets was injured by a slash and had to leave the game, the first of a number of injuries that plagued both clubs. He was forced to miss the second game as well, and with Bobby Rowe also hurt the Mets had to play the entire second game with only seven players. Montreal took advantage of the situation and evened the series with a 4-2 win. In the third game it was Montreal that suffered physically, losing defenseman Bert Corbeau with a badly injured shoulder. A 7-2 win gave Seattle a two games to one advantage in the best-of-five series, and the fans were hoping the local club would clinch the Cup in the next meeting. The fourth game of the series has gone down in history as one of the all-time classic Stanley Cup match-ups. -

John Tortorella Eager to Se

Columbus Blue Jackets News Clips Dec. 1-3, 2018 Columbus Blue Jackets PAGE 02: Columbus Dispatch: John Tortorella eager to see renovated Nassau Coliseum PAGE 04: Columbus Dispatch: Defenseman Ryan Murray tempers expectations as veteran PAGE 06: Columbus Dispatch: Blue Jackets 4, Wild 2: Five Takeaways PAGE 09: The Athletic: Oliver Bjorkstrand vs. Anthony Duclair — Blue Jackets will let high- potential youngsters fight it out for playing time PAGE 11: Columbus Dispatch: Islanders 3, Blue Jackets 2: Second-period lead erased as Islanders rally PAGE 13: Columbus Dispatch: Islanders 3, Blue Jackets 2: Second-period lead erased as Islanders rally PAGE 14: The Athletic: Blue Jackets await word on foot injury to valuable defenseman Ryan Murray PAGE 17: Columbus Dispatch: Islanders 3, Blue Jackets 2: Five takeaways Cleveland Monsters/Prospects PAGE 20: The News-Herald: 'Try Hockey for Free' with the Cleveland Monsters Dec. 15 or Feb. 10 PAGE 21: The Athletic: On the Blue Jackets farm: professional Mark Letestu, progressing Kole Sherwood and pondering Paul Bittner NHL/Websites PAGE 25: AP: To 32 and beyond: Seattle may not be end of NHL expansion PAGE 27: AP: NHL Board of Governors to vote on Seattle expansion PAGE 29: Seattle Times: More than the Metropolitans: Ahead of NHL vote, a comprehensive Seattle hockey history 1 John Tortorella eager to see renovated Nassau Coliseum By Brian Hedger, Columbus Dispatch – November 30, 2018 John Tortorella has a lot of memories of coaching in Nassau Veterans War Memorial Coliseum, which after its long-overdue renovation is now called NYCB Live’s Nassau Coliseum. The Blue Jackets will play the New York Islanders on Saturday night in the first NHL regular-season game there since the building closed for its makeover in 2015. -

Pro Lacrosse in British Columbia 1909-1924

Old School Lacrosse PROFESSIONAL LACROSSE IN BRITISH COLUMBIA ®®® 1909-1924 compiled & Edited by David Stewart-Candy Vancouver 2017 Old School Lacrosse – Professional Lacrosse in British Columbia 1909-1924 Stewart-Candy, David J. First Printing – February 14, 2012 Second Printing – October 21, 2014 This version as of February 14, 2017 Vancouver, British Columbia 2012-2017 Primary research for this book was compiled from game boxscores printed in the Vancouver Daily Province and New Westminster British Columbian newspapers. Additional newspapers used to locate and verify conflicting, damaged, or missing data were the Victoria Daily Colonist , Vancouver World & Vancouver Daily World , Vancouver Daily Sun & Vancouver Sun , and Vancouver Daily News Advertiser . Research was done by the author at the Vancouver Public Library (Robson Street branch) and New Westminster Public Library between 2002 and 2012. The Who’s Who biographies were written between September 2013 and June 2016 and originally posted at oldschoollacrosse.wordpress.com. All photographs unless otherwise noted are in public domain copyright and sourced from the City of Vancouver Archives, New Westminster City Archives, or the Canadian Lacrosse Hall of Fame collections. The photograph of Byron ‘Boss’ Johnson is taken from the book Portraits of the Premiers (1969) written by SW Jackman. Author contact information: Dave Stewart-Candy [email protected] oldschoollacrosse.wordpress.com This work is dedicated to Larry ‘Wamper’ Power and Stan Shillington... Wamper for the years of encouragement and diligently keeping on my back to ensure this project finally reached completion... Stan for his lament that statistics for field lacrosse were never set aside for future generations... until now… both these men inspired me to sit down and do for field lacrosse statistics what they did for box lacrosse.. -

88 Years of Hockey in Seattle: from Metropolitans to Thunderbirds

88 Years of Hockey in Seattle From Metroplitans to Thunderbirds The 1929-30 Seattle Eskimos were managed by Lloyd Turner (far left). BY JEFF OBERMEYER ne evening in January, 1911, Joe Patrick sat O down with his sons Lester and Frank at their home in Nelson, B.C. to discuss the Lester Patrick, left, and Frank Patrick, future of the family. Joe had pictured here from 1911, were the founders just sold his lumber business of the first professional hockey league on and was looking for a new ven- the Pacific Coast and were excellent hockey ture. Lester and Frank, both ex- players in their own right. cellent hockey players, sug- gested the family move to the west coast and start a professional hockey league – an incredibly bold idea at the time. Professional hockey was dominated by teams in Eastern Canada, and the small population of the Pacific Coast would make it hard to draw both fans and quality players. But Joe had faith in his sons, Rudy Filion played who had worked so hard for him in building his timber empire. 14 seasons in Seattle The decision was made and a month later the family moved between 1948 and 1963. to Victoria, B.C. By the following January the first Pacific A very skilled player Coast Hockey Association (PCHA) season was under- offensively, Filion was also way with teams in Vancouver, Victoria, and New known for his gentlemanly play in Westminster. the notorious rough minor leagues of the era. Photos courtesy Jeff Obermeyer www.NostalgiaMagazine.us January 2004 ! 3 The Seattle Eskimos and their opponents are ready to start a game in the Civic Arena, circa 1930. -

Sport-Scan Daily Brief

SPORT-SCAN DAILY BRIEF NHL 6/28/2021 Anaheim Ducks New York Islanders 1216549 For Luc Robitaille, Canadiens in Stanley Cup Final feels 1216574 For the Revitalized Islanders, Another ‘Heartache,’ like old times Another Almost 1216575 Barry Trotz doesn’t ‘question’ sitting Islanders’ OliVer Buffalo Sabres Wahlstrom 1216550 Pandemic has curtailed Red Wings home attendance, but 1216576 Islanders’ Anders Lee speaks out for first time since things should start picking up devastating injury 1216577 Islanders’ roster stability will be challenged this offseason Calgary Flames 1216578 LI's Kyle Palmieri would love to stay with the Islanders 1216551 Q&A: Flames coach Darryl Sutter dishes on his Stanley 1216579 Casey Cizikas not ready to talk future, but Islanders Cup experiences teammates want him back 1216580 Anders Lee says he will be ready for start of Islanders Chicago Blackhawks training camp 1216552 Former Chicago Blackhawks players and staffers allege 1216581 Nassau Coliseum leaVes UBS Arena with a lot to liVe up to management likely knew about 2010 sexual assault 1216582 Jean-Gabriel Pageau ‘likely’ needs surgery, Islanders allegat veterans want to return and ‘the best fans in this leagu 1216583 For Islanders Identity Line, Life Without Casey Cizikas Colorado Avalanche Now Something to Think About 1216553 Sunday Notes: NHL trades unlikely until after expansion 1216584 Pageau ‘a Little Banged Up’ During Playoff Run, Surgery draft, Wild in on Eichel, trouble in Chicago Possible 1216585 What’s Next for the New York Islanders Heading into the -

Manitoba Hockey History Bibliography

Manitoba Hockey Research Information Bibliography Note: Year of induction into the Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame (MHHF) for individuals and teams is indicated in parentheses. George Allard, John McFarland, Ed Sweeney, Manitoba's Hockey Heritage: Manitoba Hockey Players Foundation, 1995 * ‐ Published to honour Manitoba 125 and the 10th anniversary of the Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame. Includes biographies of Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame inductees. Biographies of those honoured in later years can be found on the Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame Inc. website www.mbhockeyhalloffame.ca. Altona Maroons Reunion Committee, Celebrating 40 Years Altona Maroons 1951‐1991: Friesen, 1991 * ‐ Pictorial history of the Altona Maroons of the South Eastern Manitoba Hockey League. A supplement covering the fifth decade of the team was published for the Maroons' Homecoming, Aug. 3‐5, 2001. * Player, manager and team president Elmer Hildebrand was inducted into the MHHF as a builder in 2007. Kathleen Arnason, Falcons Gold: Canada's First Olympic Hockey Heroes: Coastline, 2002 * ‐ Juvenile novel based on the 1920 Winnipeg Falcons hockey team that was inducted into the Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame in 1985. Illustrations by Luther Pokrant. Frank Frederickson (1985), Mike Goodman (1985), Fred (Steamer) Maxwell (1985), Wally Byron (1987) and Halldor (Slim) Halldorson (1987) are individual members of the MHHF. Richard Brignall, Forgotten Heroes Winnipeg's Hockey Heritage: J. Gordon Shillingford, 2011 * ‐ Manitoba's championship teams from the 1896 Stanley Cup winning Winnipeg Victorias to the province's last Memorial Cup champions, the 1959 Winnipeg Braves. All have been honoured by the MHHF. Brignall is a freelance writer based in Kenora, Ont. -

1934 SC Playoff Summaries

STANLEY CUP NOT AWARDED 19 19 1919 NHL FINAL FOR O’BRIEN CUP MONTRÉAL CANADIENS FIRST HALF WINNER v. OTTAWA SENATORS SECOND HALF WINNER GM GEORGE KENNEDY, PLAYING HC NEWSY LALONDE v. GM TOMMY GORMAN, PLAYING HC EDDIE GERARD CANADIENS WIN SERIES IN 5 Sunday, February 22 Thursday, February 27 OTTAWA 4 @ MONTREAL 8 MONTREAL 5 @ OTTAWA 3 FIRST PERIOD FIRST PERIOD 1. MONTREAL, Bullet Pitre 2:25 NO SCORING 2. OTTAWA, Cy Denneny 4:45 3. OTTAWA, Harry Cameron 6:15 Penalties — not published Penalties — not published SECOND PERIOD 1. OTTAWA, Harry Cameron 4:00 SECOND PERIOD 2. MONTREAL, Joe Malone 5:00 4. MONTREAL, Odie Cleghorn 5:05 3. MONTREAL, Joe Malone 10:00 5. MONTREAL, Odie Cleghorn 7:30 4. OTTAWA, Buck Boucher 19:00 6. MONTREAL, Newsy Lalonde 19:25 7. OTTAWA, Jack Darragh 19:55 Penalties — not published Penalties — not published THIRD PERIOD 5. MONTREAL, Odie Cleghorn 1:00 THIRD PERIOD 6. MONTREAL, Odie Cleghorn 6:00 GWG 8. MONTREAL, Newsy Lalonde 1:55 GWG 7. MONTREAL, Odie Cleghorn 10:00 9. OTTAWA, Jack Darragh 12:00 8. OTTAWA, Cy Denneny 18:00 10. MONTREAL, Joe Malone 14:45 11. MONTREAL, Joe Malone 15:30 Penalties — not published 12. MONTREAL, Joe Malone 18:15 GOALTENDERS — CANADIENS, Georges Vézina; SENATORS, Clint Benedict Penalties — not published Official: Harvey Pulford, Charlie McKinley GOALTENDERS — SENATORS, Clint Benedict; CANADIENS, Georges Vézina At The Arena, Ottawa Official: Harry Hyland, Jack Marshall At Jubilee Arena Saturday, March 1 Monday, March 3 OTTAWA 3 @ MONTREAL 6 MONTREAL 3 @ OTTAWA 6 FIRST PERIOD FIRST PERIOD 1. -

Nhl Morning Skate: Stanley Cup Playoffs Edition – May 27, 2019

NHL MORNING SKATE: STANLEY CUP PLAYOFFS EDITION – MAY 27, 2019 STANLEY CUP FINAL BEGINS TONIGHT IN BOSTON A rematch 49 years in the making takes center stage when the Blues and Bruins face off at TD Garden in Boston for Game 1 of the Stanley Cup Final. Prior to the game, the 2019 Stanley Cup Final Party will feature a free concert headlined by country music star Chase Rice and rapper Lil Nas X. The event - which is free and open to the public - opens at 4:30 p.m. ET at Boston's City Hall Plaza. No ticket will be required to view the performance. * Since the Final went to the best-of-seven format in 1939, the team that has won Game 1 has gone on to capture the Stanley Cup 77.2% of the time (61 of 79 series). In 2018, the Capitals rallied for a series victory and the franchise’s first-ever Stanley Cup after losing Game 1 of the Final, winning in five games. * The winner of Game 1 in any best-of-seven series owns an all-time series record of 476-219 (68.5%), including a 9-5 mark in the 2019 Stanley Cup Playoffs. * The Bruins are 6-12-1 in their previous 19 Stanley Cup Final openers (5-11 in Game 1 of best- of-seven Final), going on to capture five of their six Stanley Cups after winning Game 1 (they lost Game 1 in 2011). Boston’s six Cups are tied for the fourth-most in NHL history.