Words and Meanings OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 4/11/2013, Spi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/11/2013, Spi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Generative Lexicon

The Generative Lexicon James Pustejovsky" Computer Science Department Brandeis University In this paper, I will discuss four major topics relating to current research in lexical seman- tics: methodology, descriptive coverage, adequacy of the representation, and the computational usefulness of representations. In addressing these issues, I will discuss what I think are some of the central problems facing the lexical semantics community, and suggest ways of best ap- proaching these issues. Then, I will provide a method for the decomposition of lexical categories and outline a theory of lexical semantics embodying a notion of cocompositionality and type coercion, as well as several levels of semantic description, where the semantic load is spread more evenly throughout the lexicon. I argue that lexical decomposition is possible if it is per- formed generatively. Rather than assuming a fixed set of primitives, I will assume a fixed number of generative devices that can be seen as constructing semantic expressions. I develop a theory of Qualia Structure, a representation language for lexical items, which renders much lexical ambiguity in the lexicon unnecessary, while still explaining the systematic polysemy that words carry. Finally, I discuss how individual lexical structures can be integrated into the larger lexical knowledge base through a theory of lexical inheritance. This provides us with the necessary principles of global organization for the lexicon, enabling us to fully integrate our natural language lexicon into a conceptual whole. 1. Introduction I believe we have reached an interesting turning point in research, where linguistic studies can be informed by computational tools for lexicology as well as an appre- ciation of the computational complexity of large lexical databases. -

Studies in Ethnopragmatics, Cultural Semantics, and Intercultural Communication Ethnopragmatics and Semantic Analysis

Kerry Mullan · Bert Peeters · Lauren Sadow Editors Studies in Ethnopragmatics, Cultural Semantics, and Intercultural Communication Ethnopragmatics and Semantic Analysis [email protected] Studies in Ethnopragmatics, Cultural Semantics, and Intercultural Communication [email protected] Kerry Mullan • Bert Peeters • Lauren Sadow Editors Studies in Ethnopragmatics, Cultural Semantics, and Intercultural Communication Ethnopragmatics and Semantic Analysis 123 [email protected] Editors Kerry Mullan Bert Peeters RMIT University Australian National University Melbourne, VIC, Australia Canberra, ACT, Australia Lauren Sadow Australian National University Canberra, ACT, Australia ISBN 978-981-32-9982-5 ISBN 978-981-32-9983-2 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-32-9983-2 © Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2020 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

'Country', 'Land', 'Nation': Key Anglo English Words for Talking and Thinking About People in Places

8 ‘Country’, ‘land’, ‘nation’: Key Anglo English words for talking and thinking about people in places Cliff Goddard Griffith University, Australia [email protected] Abstract The importance of the words ‘country’, ‘land’ and ‘nation’, and their derivatives, in Anglophone public and political discourses is obvious. Indeed, it would be no exaggeration to say that without the support of words like these, discourses of nationalism, patriotism, immigration, international affairs, land rights, and post/anti- colonialism would be literally impossible. This is a corpus-assisted, lexical-semantic study of the English words ‘country’, ‘land’ and ‘nation’, using the NSM technique of paraphrase in terms of simple, cross- translatable words (Goddard & Wierzbicka 2014). It builds on Anna Wierzbicka’s (1997) seminal study of “homeland” and related concepts in European languages, as well as more recent NSM works (e.g. Bromhead 2011, 2018; Levisen & Waters 2017) that have explored ways in which discursively powerful words encapsulate historically and culturally contingent assumptions about relationships between people and places. The primary focus is on conceptual analysis, lexical polysemy, phraseology and discursive formation in mainstream Anglo English, but the study also touches on one specifically Australian phenomenon, which is the use of ‘country’ in a distinctive sense which originated in Aboriginal English, e.g. in expressions like ‘my grandfather’s country’ and ‘looking after country’. This highlights how Anglo English words can be semantically “re-purposed” in postcolonial and anti-colonial discourses. Keywords: lexical semantics, NSM, ‘nation’ concept, Anglo English, Australian English, Aboriginal English. 1. Orientation and methodology The importance of the words country, land and nation, and their derivatives, in Anglophone public and political discourses is obvious. -

Contextualizing Historical Lexicology the State of the Art of Etymological Research Within Linguistics

Contextualizing historical lexicology The state of the art of etymological research within linguistics University of Helsinki, May 15–17, 2017 Abstracts Organized by the project “Inherited and borrowed in the history of the Uralic languages” (funded by Kone Foundation) Contents I. Keynote lectures ................................................................................. 5 Martin Kümmel Etymological problems between Indo-Iranian and Uralic ................ 6 Johanna Nichols The interaction of word structure and lexical semantics .................. 9 Martine Vanhove Lexical typology and polysemy patterns in African languages ...... 11 II. Section papers ................................................................................. 12 Mari Aigro A diachronic study of the homophony between polar question particles and coordinators ............................................................. 13 Tommi Alho & Aleksi Mäkilähde Dating Latin loanwords in Old English: Some methodological problems ...................................................................................... 14 Gergely Antal Remarks on the shared vocabulary of Hungarian, Udmurt and Komi .................................................................................................... 15 Sofia Björklöf Areal distribution as a criterion for new internal borrowing .......... 16 Stefan Engelberg Etymology and Pidgin languages: Words of German origin in Tok Pisin ............................................................................................ 17 László -

Acquaintance Inferences As Evidential Effects

The acquaintance inference as an evidential effect Abstract. Predications containing a special restricted class of predicates, like English tasty, tend to trigger an inference when asserted, to the effect that the speaker has had a spe- cific kind of `direct contact' with the subject of predication. This `acquaintance inference' has typically been treated as a hard-coded default effect, derived from the nature of the predicate together with the commitments incurred by assertion. This paper reevaluates the nature of this inference by examining its behavior in `Standard' Tibetan, a language that grammatically encodes perceptual evidentiality. In Tibetan, the acquaintance inference trig- gers not as a default, but rather when, and only when, marked by a perceptual evidential. The acquaintance inference is thus a grammaticized evidential effect in Tibetan, and so it cannot be a default effect in general cross-linguistically. An account is provided of how the semantics of the predicate and the commitment to perceptual evidentiality derive the in- ference in Tibetan, and it is suggested that the inference ought to be seen as an evidential effect generally, even in evidential-less languages, which invoke evidential notions without grammaticizing them. 1 Introduction: the acquaintance inference A certain restricted class of predicates, like English tasty, exhibit a special sort of behavior when used in predicative assertions. In particular, they require as a robust default that the speaker of the assertion has had direct contact of a specific sort with the subject of predication, as in (1). (1) This food is tasty. ,! The speaker has tasted the food. ,! The speaker liked the food's taste. -

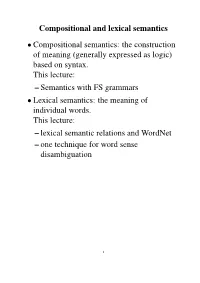

Compositional and Lexical Semantics • Compositional Semantics: The

Compositional and lexical semantics Compositional semantics: the construction • of meaning (generally expressed as logic) based on syntax. This lecture: – Semantics with FS grammars Lexical semantics: the meaning of • individual words. This lecture: – lexical semantic relations and WordNet – one technique for word sense disambiguation 1 Simple compositional semantics in feature structures Semantics is built up along with syntax • Subcategorization `slot' filling instantiates • syntax Formally equivalent to logical • representations (below: predicate calculus with no quantifiers) Alternative FS encodings possible • 2 Objective: obtain the following semantics for they like fish: pron(x) (like v(x; y) fish n(y)) ^ ^ Feature structure encoding: 2 PRED and 3 6 7 6 7 6 7 6 2 PRED 3 7 6 pron 7 6 ARG1 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 ARG1 1 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 4 5 7 6 7 6 7 6 2 3 7 6 PRED and 7 6 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 2 3 7 7 6 6 PRED like v 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 7 7 7 6 6 ARG1 6 ARG1 1 7 7 7 6 6 6 7 7 7 6 6 6 7 7 7 6 6 6 7 7 7 6 ARG2 6 6 ARG2 2 7 7 7 6 6 6 7 7 7 6 6 6 7 7 7 6 6 6 7 7 7 6 6 4 5 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 2 3 7 7 6 6 PRED fish n 7 7 6 6 ARG2 7 7 6 6 6 7 7 7 6 6 6 ARG 2 7 7 7 6 6 6 1 7 7 7 6 6 6 7 7 7 6 6 6 7 7 7 6 6 4 5 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 4 5 7 6 7 4 5 3 Noun entry 2 3 2 CAT noun 3 6 HEAD 7 6 7 6 6 AGR 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 4 5 7 6 7 6 COMP 7 6 filled 7 6 7 fish 6 7 6 SPR filled 7 6 7 6 7 6 7 6 INDEX 1 7 6 2 3 7 6 7 6 SEM 7 6 6 PRED fish n 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 ARG 1 7 7 6 6 1 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 6 7 7 6 4 5 7 4 5 Corresponds to fish(x) where the INDEX • points to the characteristic variable of the noun (that is x). -

Lectures on English Lexicology

МИНИСТЕРСТВО ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ И НАУКИ РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ ГОУ ВПО «Татарский государственный гуманитарно-педагогический университет» LECTURES ON ENGLISH LEXICOLOGY Курс лекций по лексикологии английского языка Казань 2010 МИНИСТЕРСТВО ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ И НАУКИ РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ ГОУ ВПО «Татарский государственный гуманитарно-педагогический университет» LECTURES ON ENGLISH LEXICOLOGY Курс лекций по лексикологии английского языка для студентов факультетов иностранных языков Казань 2010 ББК УДК Л Печатается по решению Методического совета факультета иностранных языков Татарского государственного гуманитарно-педагогического университета в качестве учебного пособия Л Lectures on English Lexicology. Курс лекций по лексикологии английского языка. Учебное пособие для студентов иностранных языков. – Казань: ТГГПУ, 2010 - 92 с. Составитель: к.филол.н., доцент Давлетбаева Д.Н. Научный редактор: д.филол.н., профессор Садыкова А.Г. Рецензенты: д.филол.н., профессор Арсентьева Е.Ф. (КГУ) к.филол.н., доцент Мухаметдинова Р.Г. (ТГГПУ) © Давлетбаева Д.Н. © Татарский государственный гуманитарно-педагогический университет INTRODUCTION The book is intended for English language students at Pedagogical Universities taking the course of English lexicology and fully meets the requirements of the programme in the subject. It may also be of interest to all readers, whose command of English is sufficient to enable them to read texts of average difficulty and who would like to gain some information about the vocabulary resources of Modern English (for example, about synonyms -

Sentential Negation and Negative Concord

Sentential Negation and Negative Concord Published by LOT phone: +31.30.2536006 Trans 10 fax: +31.30.2536000 3512 JK Utrecht email: [email protected] The Netherlands http://wwwlot.let.uu.nl/ Cover illustration: Kasimir Malevitch: Black Square. State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. ISBN 90-76864-68-3 NUR 632 Copyright © 2004 by Hedde Zeijlstra. All rights reserved. Sentential Negation and Negative Concord ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus Prof. Mr P.F. van der Heijden ten overstaan van een door het College voor Promoties ingestelde commissie, in het openbaar te verdedigen in de Aula der Universiteit op woensdag 15 december 2004, te 10:00 uur door HEDZER HUGO ZEIJLSTRA geboren te Rotterdam Promotiecommissie: Promotores: Prof. Dr H.J. Bennis Prof. Dr J.A.G. Groenendijk Copromotor: Dr J.B. den Besten Leden: Dr L.C.J. Barbiers (Meertens Instituut, Amsterdam) Dr P.J.E. Dekker Prof. Dr A.C.J. Hulk Prof. Dr A. von Stechow (Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen) Prof. Dr F.P. Weerman Faculteit der Geesteswetenschappen Voor Petra Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................ I ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................V 1 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................1 1.1 FOUR ISSUES IN THE STUDY OF NEGATION.......................................................1 -

Chapter 1 Negation in a Cross-Linguistic Perspective

Chapter 1 Negation in a cross-linguistic perspective 0. Chapter summary This chapter introduces the empirical scope of our study on the expression and interpretation of negation in natural language. We start with some background notions on negation in logic and language, and continue with a discussion of more linguistic issues concerning negation at the syntax-semantics interface. We zoom in on cross- linguistic variation, both in a synchronic perspective (typology) and in a diachronic perspective (language change). Besides expressions of propositional negation, this book analyzes the form and interpretation of indefinites in the scope of negation. This raises the issue of negative polarity and its relation to negative concord. We present the main facts, criteria, and proposals developed in the literature on this topic. The chapter closes with an overview of the book. We use Optimality Theory to account for the syntax and semantics of negation in a cross-linguistic perspective. This theoretical framework is introduced in Chapter 2. 1 Negation in logic and language The main aim of this book is to provide an account of the patterns of negation we find in natural language. The expression and interpretation of negation in natural language has long fascinated philosophers, logicians, and linguists. Horn’s (1989) Natural history of negation opens with the following statement: “All human systems of communication contain a representation of negation. No animal communication system includes negative utterances, and consequently, none possesses a means for assigning truth value, for lying, for irony, or for coping with false or contradictory statements.” A bit further on the first page, Horn states: “Despite the simplicity of the one-place connective of propositional logic ( ¬p is true if and only if p is not true) and of the laws of inference in which it participate (e.g. -

Lexicology and Lexicography

LEXICOLOGY AND LEXICOGRAPHY 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 1.1.Study programme M.A. level (graduate) 1.6. Type of instruction (number of hours 15L + 15S (undergraduate, graduate, integrated) L + S + E + e-learning) 1.2. Year of the study programme 1st & 2nd 1.7. Expected enrollment in the course 30 Lexicology and lexicography Marijana Kresić, PhD, Associate 1.3. Name of the course 1.8. Course teacher professor 1.4. Credits (ECTS) 5 1.9. Associate teachers Mia Batinić, assistant elective Croatian, with possible individual 1.5. Status of the course 1.10. Language of instruction sessions in German and/or English 2. COURSE DESCRIPTION The aims of the course are to acquire the basic concepts of contemporary lexicology and lexicography, to become acquainted with its basic terminology as well as with the semantic and psycholinguistic foundations that are relevant for understanding problems this field. The following topics will be covered: lexicology and lexicography, the definition of 2.1. Course objectives and short words, word formation, semantic analysis, analysis of the lexicon, semantic relations between words (hyperonomy, contents hyponomy, synonymy, antonymy, homonymy, polysemy, and others), the structure of the mental lexicon, the micro- and macro structure of dictionaries, different types of dictionaries. Moreover, students will be required to conduct their own lexicographic analysis and suggest the lexicographic design of a selected lexical unit. 2.2. Course enrolment requirements No prerequisites. and entry competences required for the course -

Cliff GODDARD & Anna WIERZBICKA, Words And

Lexis Journal in English Lexicology Book reviews | 2019 Cliff GODDARD & Anna WIERZBICKA, Words and Meanings. Lexical Semantics Across Domains, Languages and Cultures Oxford University Press, 2016, 2014, 316 pages Cathy Parc Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/lexis/3514 DOI: 10.4000/lexis.3514 ISSN: 1951-6215 Publisher Université Jean Moulin - Lyon 3 Electronic reference Cathy Parc, « Cliff GODDARD & Anna WIERZBICKA, Words and Meanings. Lexical Semantics Across Domains, Languages and Cultures », Lexis [Online], Book reviews, Online since 25 August 2019, connection on 23 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/lexis/3514 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ lexis.3514 This text was automatically generated on 23 September 2020. Lexis is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Cliff Goddard & Anna Wierzbicka, Words and Meanings. Lexical Semantics Across... 1 Cliff GODDARD & Anna WIERZBICKA, Words and Meanings. Lexical Semantics Across Domains, Languages and Cultures Oxford University Press, 2016, 2014, 316 pages Cathy Parc REFERENCES Cliff Goddard, Anna Wierzbicka Words and Meanings. Lexical Semantics Across Domains, Languages and Cultures. Oxford University Press, London, 2016 ISBN: 978-0-19-878355-8, Price: £44.95, 316 pages 1 Words & Meanings. Lexical Semantics across Domains, Languages, & Cultures was written by Cliff Goddard, Professor of Linguistics at Griffith University, and Anna Wierzbicka, Professor of Linguistics at Australian National University, -

The Art of Lexicography - Niladri Sekhar Dash

LINGUISTICS - The Art of Lexicography - Niladri Sekhar Dash THE ART OF LEXICOGRAPHY Niladri Sekhar Dash Linguistic Research Unit, Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata, India Keywords: Lexicology, linguistics, grammar, encyclopedia, normative, reference, history, etymology, learner’s dictionary, electronic dictionary, planning, data collection, lexical extraction, lexical item, lexical selection, typology, headword, spelling, pronunciation, etymology, morphology, meaning, illustration, example, citation Contents 1. Introduction 2. Definition 3. The History of Lexicography 4. Lexicography and Allied Fields 4.1. Lexicology and Lexicography 4.2. Linguistics and Lexicography 4.3. Grammar and Lexicography 4.4. Encyclopedia and lexicography 5. Typological Classification of Dictionary 5.1. General Dictionary 5.2. Normative Dictionary 5.3. Referential or Descriptive Dictionary 5.4. Historical Dictionary 5.5. Etymological Dictionary 5.6. Dictionary of Loanwords 5.7. Encyclopedic Dictionary 5.8. Learner's Dictionary 5.9. Monolingual Dictionary 5.10. Special Dictionaries 6. Electronic Dictionary 7. Tasks for Dictionary Making 7.1. Panning 7.2. Data Collection 7.3. Extraction of lexical items 7.4. SelectionUNESCO of Lexical Items – EOLSS 7.5. Mode of Lexical Selection 8. Dictionary Making: General Dictionary 8.1. HeadwordsSAMPLE CHAPTERS 8.2. Spelling 8.3. Pronunciation 8.4. Etymology 8.5. Morphology and Grammar 8.6. Meaning 8.7. Illustrative Examples and Citations 9. Conclusion Acknowledgements ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) LINGUISTICS - The Art of Lexicography - Niladri Sekhar Dash Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary The art of dictionary making is as old as the field of linguistics. People started to cultivate this field from the very early age of our civilization, probably seven to eight hundred years before the Christian era.