E12 UNDERSTANDING CRYSTAL STRUCTURES 1 Introduction in This

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Kapustinskii Equation

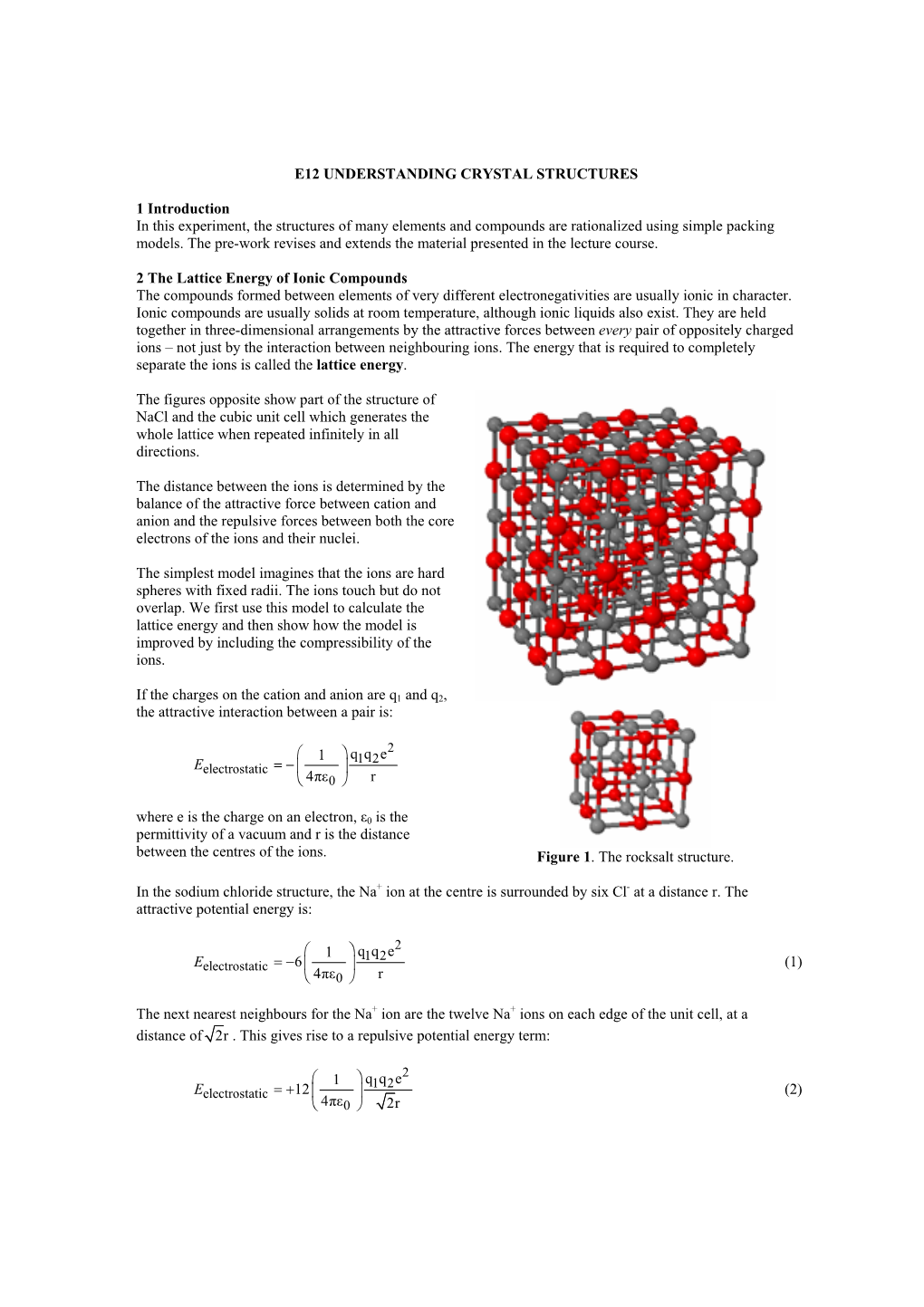

III-1 1 PART THREE: Ionic Bonding In . Molecules And Solids So far we have defined several energies of interaction between charged particles. - Ionization Energy - Electron Affinity - Coulombic (Electrostatic) Attraction & Repulsion. We now use these to look at further bonding properties: Mostly solids. Why are solids important? Catalysts Ad & Ab – Sorbents Lasers Fibre Optics Magnetic Memories Optical Switching (Computers) Batteries Fluorescent Lights Superconductors LED’s ………. III-2 2 We Need To Start At The Beginning One of the simplest ionic solids is sodium chloride (NaCl). Various depictions of the rocksalt structure. Not all will be met in this course. III-3 3 Discrete NaCl molecules can exist in the gas phase. NaCl(g) → Na(g) + Cl(g) ∆H for this reaction is called the Bond Dissociation Energy (409 kJ mol-1) • We can judge the stability of solids whether they form or not by looking at the free energy change for: M+(g) + X-(g) → MX(s) ∆G = ∆H - T∆S • If ∆G is –ve then spontaneous. • Note: Process of Lattice formation (solid ) is very exothermic at room temperature (∆S may be neglected). III-4 4 • We will use ∆H’s (enthalpy). Born Haber Cycle + - Na (g) + Cl (g) IP EA Electrostatic (U) _1 Attraction Na(g) + 2 Cl2(g) NaCl(g) ∆H f ( NaCl ) We can calculate U from this cycle Can You Do It ?: watch the signs However: NaCl(g) is NOT NaCl(s) III-5 5 - We want to get an idea of how stable different solids are. - Then U is more complicated. WHY? Sodium Chloride Lattice Cubic Na Cl + Cl Each Na has 2r - 3r Na 6 near neighbour Cl Cl Na Each Cl- has Na + r Cl 6 near neighbour Na • The attractive energy between a Na+ and its 6 near neighbour Cl- is offset by repulsion from 12 next near neighbour Na+. -

Pauling's Rules: Goldschmidt's Structural Principles for Ionic Crystals Were Summarized by Linus Pauling in a Set of 5 Rules

CRYSTALS THAT CANNOT BE DESCRIBED IN TERMS OF INTERSTITIAL FILLING OF A CLOSE-PACKED STRUCTURE 154 CsCl STRUCTURE → → → Adoption by chlorides, bromides and iodides of larger cations 155 MoS2 STRUCTURE • layered structure → → → 156 •both MoS2 and CdI2 are LAYERED structures •MoS2 layers are edge-linked MoS6 trigonal prisms •CdI2 layers are edge-linked CdI6 octahedra 157 MoS6 trigonal prisms AsNi6 trigonal prisms 158 COVALENT NETWORK STRUCTURES Concept of CONNECTEDNESS (P) of a network connecting structural units (atoms or groups) e.g. Structures of Non-Metallic Elements The "8-N Rule“ connectedness = 8 – # valence electrons P = 8 – N P = 1 e.g. I2 dimers Space group: Cmca orthorhombic 159 STRUCTURES OF THE ELEMENTS P = 1 e.g. I2 DIMERS FCC metal 160 P = 2 e.g. S8 RINGS • the packing approximates a distorted close-packing arrangement • apparently 11-coordinate (3 left + 5 in-plane + 3 right) 161 P = 2 e.g. gray selenium HELICAL CHAINS Chains form a 3-fold Helix down c • this allotrope of Se is an excellent photoconductor 162 ALLOTROPY A polymorph is a distinct crystalline form of a substance (e.g., zinc blende & wurtzite). Polymorphs of elements are known as allotropes. 163 P = 3 e.g. gray As, Bi LAYERS Interlinked 6-membered rings 164 165 P = 3 e.g. sp2 carbon LAYERS and CAGES 166 P = 4 e.g. sp3 carbon DIAMOND FRAMEWORK 167 P = 4 Networks Structures with the Diamond FRAMEWORK 168 Cristobalite: a high- temperature polymorph of quartz cuprite: a cubic semiconductor CNCu : 2 CNO : 4 O Cu 169 SILICATE MINERALS 4- Networks of corner-sharing tetrahedral SiO4 Units Chemical formula hints at network structure: • terminal oxygens count as 1 • bridging oxygens count as 1/2 170 Si:O = 1:4 4- P = 0, Orthosilicate, SiO4 e.g. -

Solids Close-Packing

Solids Solid State Chemistry, a subdiscipline of Inorganic Chemistry, primarily involves the study of extended solids. •Except for helium*, all substances form a solid if sufficiently cooled at 1 atm. •The vast majority of solids form one or more crystalline phases – where the atoms, molecules, or ions form a regular repeating array (unit cell). •The primary focus will be on the structures of metals, ionic solids, and extended covalent structures, where extended bonding arrangements dominate. •The properties of solids are related to its structure and bonding. •In order to understand or modify the properties of a solid, we need to know the structure of the material. •Crystal structures are usually determined by the technique of X-ray crystallography. •Structures of many inorganic compounds may be initially described in terms of simple packing of spheres. Close-Packing Square array of circles Close-packed array of circles Considering the packing of circles in two dimensions, how efficiently do the circles pack for the square array? in a close packed array? 1 Layer A Layer B ccp cubic close packed hcp hexagonal close packed 2 Layer B (dark lines) CCP HCP In ionic crystals, ions pack themselves so as to maximize the attractions and minimize repulsions between the ions. •A more efficient packing improves these interactions. •Placing a sphere in the crevice or depression between two others gives improved packing efficiency. hexagonal close packed (hcp) ABABAB Space Group: P63/mmc cubic close packed (ccp) ABCABC Space Group: Fm3m 3 Face centered cubic (fcc) has cubic symmetry. Atom is in contact with three atoms above in layer A, six around it in layer C, and three atoms in layer B. -

Madelung Constant, A

SolidSolid StateState TheoryTheory PhysicsPhysics 545545 Structure of Matter • Properties of materials are a function of their: Atomic Structure Bonding Structure Crystal Structure Imperfections • If these various structures are known then the properties of the material can be determined. • We can tailor these properties to achieve the material needed for a particular product. ¾¾ PropertiesProperties ofof aa materialmaterial z DependsDepends onon bondingbonding ofof atomsatoms thatthat formform thethe materialmaterial z DictatesDictates howhow itit interactsinteracts andand respondsresponds toto thethe worldworld aroundaround it.it. TheseThese include:include: • Physical Properties z Form (Gas, Liquid, Solid) ,Hardness (Rigid, Ductile, Strength), Reactivity • Thermal Properties z Heat capacity, Thermal conductivity, • Electrical Properties z Conductivity, Dielectric Strength, Polarizability • Magnetic Properties z Magnetic permittivity, • Optical Properties z Spectral absorption, Refractive index, Birefringence, Polarization, Atomic Theory • Nucleus of the atom is made up of protons (+) and neutrons (-) • Number of electrons surrounding the nucleus must equal the number of protons (free state-electrically neutral). • Atomic Number - the number of protons in the nucleus • Atomic Number determines the properties and characteristics of materials Atomic Structures And Atomic Bonding • gives chemical identification Nucleus • consists of protons and neutrons • # of protons = atomic number • # of neutrons gives isotope number Electrons • participate -

Solutions of Alkali Halides in Water Conduct Electricity

Chapter 7 The Crystalline Solid State 97 CHAPTER 7: THE CRYSTALLINE SOLID STATE 7.1 a. Oh b. D4h c. Oh d. Td e. The image in Figure 7.10, which has D3d symmetry, actually consists of three unit cells. For an image of a single unit cell, which has point group C2h, see page 556 in the Greenwood and Earnshaw reference in the “General References” section. 7.2 The unit-cell dimension is 2r, the volume is 8r3. Since this cell contains one molecule 4/3r 3 whose volume is 4/3 π r3, the fraction occupied is 0.524 52.4%. 8r 3 7.3 The unit-cell length for a primitive cubic cell is 2r. Using the Pythagorean theorem, we 2 2 can calculate the face diagonal as 2r 2r 2.828rand the body diagonal as 2 2 2.828r 2r 3.464r . Each corner atom contributes r to this distance, so the diameter of the body center is 1.464 r and the radius is 0.732 r, 73.2% of the corner atom size. 7.4 a. A face-centered cubic cell is shown preceding Exercise 7.1 in Section 7.1.1. The cell contains 6 × 1 = 3 atoms at the centers of the faces and 8 × 1 = 1 atom at the corners, a 2 8 4 16 total of 4 atoms. The total volume of these 4 atoms 4 r 3 r 3, where r is the 3 3 radius of each atom (treated as a sphere). As can be seen in the diagram, the diagonal of a face of the cube = 4r. -

Structures of Solids

Structures of solids LATTICE ≣ An infinite array of points in space, in which each point has identical surroundings to all others. CRYSTAL STRUCTURE ≣ The periodic arrangement of atoms in the crystal. It can be described by associating with each lattice point a group of atoms called the basis (motif). Lattice + Basis = Crystal Structure • Don't mix up atoms with lattice points • Lattice points are infinitesimal points in space • Atoms are physical objects • Lattice Points do not necessarily lie at the centre of atoms UNIT CELL ≣ The smallest component of the crystal, which when stacked together with pure translational repetition reproduces the whole crystal. Primitive (P)unit cells contain only a single lattice point Hexagonal pattern of a single layer of GRAPHITE Counting Lattice Points/Atoms in 2D Lattices •Unit cell is Primitive (1 lattice point) but contains TWO atoms in the basis 1 •Atoms at the corner of the 2D unit cell contribute only /4 to unit cell count 1 •Atoms at the edge of the 2D unit cell contribute only /2 to unit cell count •Atoms within the 2D unit cell contribute 1 (i.e. uniquely) to that unit cell The 14 possible BRAVAIS LATTICES Close-Packed Structures (Coordination Number = 12; 74% of space is occupied) Hexagonal Close-Packing (HCP): ABABAB.... 2 lattice points in the unit 2 1 1 cell: (0, 0, 0) ( /3, /3, /2) Cubic Close-Packing (CCP): ABCABC.... 4 lattice points in the unit 1 1 cell: (0, 0, 0) (0, /2, /2) 1 1 1 1 ( /2, 0, /2) ( /2, /2, 0) A non-closed-packed structure adopted by some metals • Two lattice points -

The Electronic Structure of F-Centres in Alkali Halide Crystals

Revista Brasileira de Física, Vol. 12, nP 1, 1982 The Electronic Structure of F-Centres in Alkali Halide Crystals ZELEK S. HERMAN Quantum Chemistry Group, University of Uppsala, Box 518, 75120 Uppsala 1, Sweden and GENE BARNETT Division of Research National lnstitute on Drug Abuse Rockville, Maryland 20852 USA Recebido em 10 de Outubro de 1981 A method is presented for estimating the number of bound sta- tes of different orbital angular momentum quantum number for an F-cen- tre residing in an alkali halide crystal through the introduction of a spherically symmetric potential well of finite depth. The method is il- lustrated through its application to the F-centre in sodium chloride,and the resul ts for F-centres in various a1 kal i hal ide lattices are tabula- ted. The results provide a good account of the experimental features of the F-centre including the K-band which we suggest is due to transi- tions from the 2p to excited levels. Values for the effective range of penetration of the defect electron with the neighbouring cation in dif- ferent crystals are determined by requiring that the well depth be in- dependent of orbital angular momentum quantum number. The technique is applied to estimate the Madelung constant nd Madelung potential for the host crystal. Apresenta-se um método para est mar o número de estados 1 i- gados de diferente momento angular orbital para um F-centro residente em um cristal de haleto alcal ino, pela introdução de um polo de poten- cial esfer icamente simétrico de profundidade infinita. -

Computation of Madelung Energies for Ionic Crystals of Variable Stoichiometries and Mixed Valencies and Their Application in Lithium-Ion Battery Voltage Modelling

Computation of Madelung Energies for Ionic Crystals of Variable Stoichiometries and Mixed Valencies and their application in Lithium-ion battery voltage modelling K. Ragavendran, D. Vasudevan, A. Veluchamy and Bosco Emmanuel* Central Electrochemical Research Institute, Karaikudi-630 006, India Abstract Electrostatic energy (Madelung energy) is a major constituent of the cohesive energy of ionic crystals. Several physicochemical properties of these materials depend on the response of their electrostatic energy to a variety of applied thermal, electrical and mechanical stresses. In the present study, a method has been developed based on Ewald’s technique, to compute the electrostatic energy arising from ion-ion interactions in ionic crystals like LixMn2O4 with variable stoichiometries and mixed valencies. An interesting application of this method in computing the voltages of lithium ion batteries employing spinel cathodes is presented for the first time. The advantages of the present method of computation over existing methods are also discussed. __________________________ * author for correspondence Introduction Electrostatic energy of ionic crystals [1-3] is an important constituent of the cohesive energy [4] of these crystals. Various physicochemical properties such as melting points, heats of fusion and evaporation and activation energies for formation and diffusion of electronic and atomic point defects are related to the solid-state cohesion [5]. Response of the lattice energy towards a variety of applied thermal, electrical and mechanical stresses lead to piezoelectric, ferroelectric and electrochromic properties of these materials. Madelung energy computations have also recently generated much interest [6-9]. A Madelung model has been used to predict the dependence of lattice parameter on the nanocrystal size [6]. -

Ionic Bonding, an Introduction to Materials and to Spreadsheets

Ionic Bonding, An Introduction to Materials and to Spreadsheets Mike L. Meier Department of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science University of California, Davis Davis, CA 95616 Keywords Ionic bonding, NaCl-type structure, halite, interatomic spacing, bulk modulus, shear modulus, Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio. Prerequisite Knowledge The student should be familiar with the basics of ionic bonding, including the attractive and repulsive energy terms, their relationship to interatomic forces, the relationships between bulk, shear and Young’s elastic moduli and the effect of temperature on lattice energy. They should also be familiar with the basics of simple crystal structures, particularly the halite structure. Objective In this experiment the energies and forces involved in ionic bonding plus selected physical properties will be computed. The energy-spacing and force-spacing results will be graphed and the calculated properties will be compared to the values available in the literature. All calculations plus the graphing will be done using a spreadsheet. This spreadsheet program will be constructed using a logical, progressive approach which allows one to carefully examine each aspect of the program as it is being built. This spreadsheet will also be somewhat generalized, allowing one to calculate the bonding energies and forces for a number of ionic substances. This exercise will involve first performing these calculations for KCl and, when you are sure your program works correctly, repeating the calculations for at least one of the other compounds listed in tables 1 and 2. The results will be compared to those compiled in table 2. Equipment and Materials 1. Personal computers, at least one for every two students, running a spreadsheet program such as Quattro Pro, Excel, etc., and a printer 2. -

Ionic Radii with Coordination Number

Basic Structural Chemistry Crystalline state Structure types Degree of Crystallinity Crystalline – 3D long range order Single-crystalline Polycrystalline - many crystallites of different sizes and orientations (random, oriented) Paracrystalline - short and medium range order, lacking long range order Amorphous – no order, random Degree of Crystallinity z Single Crystalline z Polycrystalline z Semicrystalline z Amorphous Grain boundaries Crystal Structure •The building blocks of these two are identical, but different crystal faces are developed • Cleaving a crystal of rocksalt Crystals • Crystal consist of a periodic arrangement of structural motifs = building blocks • Building block is called a basis: an atom, a molecule, or a group of atoms or molecules • Such a periodic arrangement must have translational symmetry such that if you move a building block by a distance: T = n1a + n2b + n3c where n1, n2 , and n3 are integers, and a, b, c are vectors. then it falls on another identical building block with the same orientation. • If we remove the building blocks and replace them with points, then we have a point lattice or Bravais lattice. Planar Lattice 2D Five Planar Lattices Unit Cell: An „imaginary“ parallel sided region of a structure from which the entire crystal can be constructed by purely translational displacements Contents of unit cell represents chemical composition Space Lattice: A pattern that is formed by the lattice points that have identical environment. Coordination Number (CN): Number of direct neighbours of a given atom (first coordination sphere) Crystal = Periodic Arrays of Atoms Translation Vectors c a,b,c b Lattice point (Atom, molecule, group of molecules,…) a Primitive Cell: • Smallest building block for the crystal lattice. -

Crystal Structure

Crystalline State Basic Structural Chemistry Structure Types Lattice Energy Pauling Rules 1 Degree of Crystallinity Crystalline – 3D long range order Single-crystalline Polycrystalline - many crystallites of different sizes and orientations (random, oriented) Paracrystalline - short and medium range order, lacking long range order 2 Amorphous – no order, random Degree of Crystallinity Single Crystalline Polycrystalline Semicrystalline Amorphous Grain boundaries 3 Degree of Crystallinity A crystalline solid: HRTEM image of strontium titanate. Brighter atoms are Sr and darker are Ti. A TEM image of amorphous interlayer at the Ti/(001)Si interface in an as-deposited sample. 4 Crystal Structure The building blocks of these two are identical, but different crystal faces are developed Conchoidal fracture in chalcedony Cleaving a crystal of rocksalt 5 X-ray structure analysis with single crystals 6 Single crystal X-ray diffraction structure analysis a four circle X-ray diffractometer 7 CAD4 (Kappa Axis Diffractometer) 8 IPDS (Imaging Plate Diffraction System) 9 Crystals • Crystal consist of a periodic arrangement of structural motifs = building blocks • Building block is called a basis: an atom, a molecule, or a group of atoms or molecules • Such a periodic arrangement must have translational symmetry such that if you move a building block by a distance: T n1a n2b n3c where n1, n2 , and n3 are integers, and a, b, c are vectors. then it falls on another identical building block with the same orientation. • If we remove the building blocks and replace them with points, then we have a point lattice or Bravais lattice. 10 Planar Lattice 2D LATTICE A lattice is the geometrical pattern formed by points representing the locations of these basis or motifs. -

Fracture Toughness and Surface Energies of Minerals: Theoretical Estimates for Oxides, Sulphides, Silicates and Halides D

Minerals Engineering 15 (2002) 1027–1041 This article is also available online at: www.elsevier.com/locate/mineng Fracture toughness and surface energies of minerals: theoretical estimates for oxides, sulphides, silicates and halides D. Tromans a,*, J.A. Meech b,1 a Department of Metals and Materials Engineering, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1W5 b Department of Mining and Mineral Process Engineering, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1W5 Received 6 August 2002; accepted 13 September 2002 Abstract Theoretical estimates of the ideal fracture toughness and surface energies of 48 minerals have been modelled by treating them as ionic solids, using the Born model of bonding. Development of the toughness model required calculation of the crystal binding enthalpy from thermodynamic data and the use of published elastic constants for single crystals. The principal minerals studied were oxides, sulphides and silicates, plus a few halides and sulphates. The study showed grain boundary fracture is most likely in single- phase polycrystalline minerals. However, the fracture toughness for grain boundary cracking in pure minerals is not significantly lower than that for intragranular cracking. The computed critical stress intensity values for intragranular cracking, KIC, ranged from 1=2 À2 0.131 to 2.774 MPa m . The critical energy release rates for intragranular cracking, GIC, ranged from 0.676 to 20.75 J m . The results are discussed with relevance to mineral comminution, including energy considerations, particle impact efficiency, and lower limiting particle size. Ó 2002 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Comminution; Crushing; Grinding; Particle size 1.