Will Avalanche Photodiode Arrays Ever Reach 1 Megapixel?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Al0.48 In0.52 As Superlattice Avalanche Photodiodes On

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Engineering of impact ionization characteristics in In0.53Ga0.47As/ Al0.48In0.52As superlattice avalanche photodiodes on InP substrate S. Lee1, M. Winslow2, C. H. Grein2, S. H. Kodati1, A. H. Jones3, D. R. Fink1, P Das4, M. M. Hayat4, T. J. Ronningen1, J. C. Campbell3 & S. Krishna1* We report on engineering impact ionization characteristics of In0.53Ga0.47As/Al0.48In0.52As superlattice avalanche photodiodes (InGaAs/AlInAs SL APDs) on InP substrate to design and demonstrate an APD with low k-value. We design InGaAs/AlInAs SL APDs with three diferent SL periods (4 ML, 6 ML, and 8 ML) to achieve the same composition as Al0.4Ga0.07In0.53As quaternary random alloy (RA). The simulated results of an RA and the three SLs predict that the SLs have lower k-values than the RA because the electrons can readily reach their threshold energy for impact ionization while the holes experience the multiple valence minibands scattering. The shorter period of SL shows the lower k-value. To support the theoretical prediction, the designed 6 ML and 8 ML SLs are experimentally demonstrated. The 8 ML SL shows k-value of 0.22, which is lower than the k-value of the RA. The 6 ML SL exhibits even lower k-value than the 8 ML SL, indicating that the shorter period of the SL, the lower k-value as predicted. This work is a theoretical modeling and experimental demonstration of engineering avalanche characteristics in InGaAs/AlInAs SLs and would assist one to design the SLs with improved performance for various SWIR APD application. -

Leds As Single-Photon Avalanche Photodiodes by Jonathan Newport, American University

LEDs as Single-Photon Avalanche Photodiodes by Jonathan Newport, American University Lab Objectives: Use a photon detector to illustrate properties of random counting experiments. Use limiting probability distributions to perform statistical analysis on a physical system. Plot histograms. Condition a detector’s signal for further electronic processing. Use a breadboard, power supply and oscilloscope to construct a circuit and make measurements. Learn about semiconductor device physics. Reading: Taylor 3.2 – The Square-Root Rule for a Counting Experiment pp. 48-49 Taylor 5.1-5.3 – Histograms and the Normal Distribution pp. 121-135 Taylor Ch. 11 – The Poisson Distribution pp. 245-254 Taylor Problem 5.6 – The Exponential Distribution p. 155 Experiment #1: Lighting an LED A Light-Emitting Diode is a non-linear circuit element that can produce a controlled amount of light. The AND113R datasheet shows that the luminous intensity is proportional to the current flowing through the LED. As illustrated in the IV curve shown below, the current flowing through the diode is in turn proportional to the voltage across the diode. Diodes behave like a one-way valve for current. When the voltage on the Anode is more positive than the voltage on the Cathode, then the diode is said to be in Forward Bias. As the voltage across the diode increases, the current through the diode increases dramatically. The heat generated by this current can easily destroy the device. It is therefore wise to install a current-limiting resistor in series with the diode to prevent thermal runaway. When the voltage on the Cathode is more positive than the voltage on the Anode, the diode is said to be in Reverse Bias. -

Thermionic and Gaseous State Diodes

THERMIONIC AND GASEOUS STATE DIODES Thermionic and gaseous state (vacuum tube) diodes Thermionic diodes are thermionic-valve devices (also known as vacuum tubes, tubes, or valves), which are arrangements of electrodes surrounded by a vacuum within a glass envelope. Early examples were fairly similar in appearance to incandescent light bulbs. In thermionic valve diodes, a current through the heater filament indirectly heats the cathode, another internal electrode treated with a mixture of barium and strontium oxides, which are oxides of alkaline earth metals; these substances are chosen because they have a small work function. (Some valves use direct heating, in which a tungsten filament acts as both heater and cathode.) The heat causes thermionic emission of electrons into the vacuum. In forward operation, a surrounding metal electrode called the anode is positively charged so that it electrostatically attracts the emitted electrons. However, electrons are not easily released from the unheated anode surface when the voltage polarity is reversed. Hence, any reverse flow is negligible. For much of the 20th century, thermionic valve diodes were used in analog signal applications, and as rectifiers in many power supplies. Today, valve diodes are only used in niche applications such as rectifiers in electric guitar and high-end audio amplifiers as well as specialized high-voltage equipment. Semiconductor diodes A modern semiconductor diode is made of a crystal of semiconductor like silicon that has impurities added to it to create a region on one side that contains negative charge carriers (electrons), called n-type semiconductor, and a region on the other side that contains positive charge carriers (holes), called p-type semiconductor. -

CHAPTER 11 HPD (Hybrid Photo-Detector)

CHAPTER 11 HPD (Hybrid Photo-Detector) HPD (Hybrid Photo-Detector) is a completely new photomultiplier tube that incorporates a semiconductor element in an evacuated elec- tron tube. In HPD operation, photoelectrons emitted from the photo- cathode are accelerated to directly strike the semiconductor where their numbers are increased. Features offered by the HPD are extremely little fluctuation during the multiplication, high electron resolution, and excellent stability. © 2007 HAMAMATSU PHOTONICS K. K. 210 CHAPTER 11 HPD (Hybrid Photo-Detector) 11.1 Operating Principle of HPDs As shown in Figure 11-1, an HPD consists of a photocathode for converting light into photoelectrons and a semiconductor element (avalanche diode or AD) which is the target for "electron bombardment" by photo- electrons. The HPD operates on the following principle: when light enters the photocathode, photoelectrons are emitted according to the amount of light; these photoelectrons are accelerated by a high-intensity electric field of a few kilovolts to several dozen kilovolts applied to the photocathode; they are then bombarded onto the target semiconductor where electron-hole pairs are generated according to the incident energy of the photoelectrons. This is called "electron bombardment gain". A typical relation between this electron bom- bardment gain and the photocathode supply voltage is plotted in Figure 11-2. In principle, this electron bom- bardment gain is proportional to the photocathode supply voltage. However, there is actually a loss of energy in the electron bombardment due to the insensitive surface layer of the semiconductor, so their proportional relation does not hold at a low voltage. In Figure 11-2, the voltage at a point on the voltage axis (horizontal axis) where the dotted line intersects is called the threshold voltage [Vth]. -

Avalanche Diode Detector Unit

A large area avalanche photodiode detector system with USB interface 1. Introduction When measuring low light levels, a vacuum tube photomultiplier tube or some form of solid-state detector which relies on multiplication (e.g. Avalanche diode, Geiger avalanche diode, silicon photomultiplier) is normally used. Vacuum tube photomultipliers have the advantage that a large photosensitive area is available, in contrast to most solid-state devices, which, in general, allow detection over a small area. Avalanche photodiodes make excellent detectors, and here we describe a detector assembly developed around a large area device, 10 mm diameter. This detector unit is designed to detect low light levels and is based around a detector module, commercially available from AP Technology, (www.advancedphotonix.com) part# 197-70-74-661. The detector module is supplied as just that, a small box with flying leads, requiring appropriate low voltage dc power supplies. It does include a thermoelectric cooler and the avalanche diode’s high voltage bias supply. Here we describe how this module was integrated in a photo-detection subsystem, powered from the mains and controlled either from an internal potentiometer or through a computer interface. The completed unit can operate as a stand-alone, manually adjusted unit and powered from a +5V / 2.5A power supply, providing an analogue output in the range 0 to +1V into a 50 Ω (or greater) load over a typical 10 MHz bandwidth. It can also operate as a USB-controlled device, where the detector gain can be remotely set and where output readings and operating conditions can be monitored. -

Avalanche Photodiodes Arrays

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 2004 Avalanche photodiodes arrays Daniel Ma Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Ma, Daniel, "Avalanche photodiodes arrays" (2004). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Avalanche Photodiodes Arrays By Daniel Ma B.S. College of Engineering, Rochester Institute of Technology (1998) A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the Chester F. Carlson Center for Imaging Science of the College of Science Rochester Institute of Technology August 2004 Signature of the Author __D_a_n_i e_1 _M_a_______ _ Accepted by Harvey E. Rhody .y/h~~s- ) Coordinator, M.S. Degree Program Date CHESTERF.CARLSON CENTER FOR IMAGING SCIENCE COLLEGE OF SCIENCE ROCHESTER INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY ROCHESTER, NEW YORK CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL M.S. DEGREE THESIS The M.S. Degree Thesis of Daniel Ma has been examined and approved by the thesis committee as satisfactory for the thesis requirement for the Master of Science degree Zoran Ninkov Dr. Zoran Ninkov, Thesis Advisor Lynn Fuller Dr. Lynn Fuller Jonathan S. Arney Dr. Jon Arney Date ii THESIS RELEASE PERMISSION ROCHESTER INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY COLLEGE OF SCIENCE CHESTER F. CARLSON CENTER FOR IMAGING SCIENCE Title of Thesis: Avalanche Photodiode Arrays I, Daniel Ma, hereby grant permission to the Wallace Memorial Library of R.I.T. -

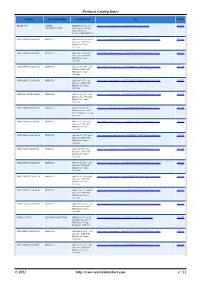

Products Catalog Index

Products Catalog Index PART NO. MANUFACTURER DESCRIPTION URL PRICE DFLR1400-7 DIODES DFLR1400 Series 1 A http://www.searchdatasheet.com/DFLR1400-7-datasheet.html QUOTE INCORPORATED 400 V Surface Mount Glass Passivated Rectifier-POWERDI-123 GRM155R61C474KE01D MURATA 0402 0.47 uF 16 V ±10% http://www.searchdatasheet.com/GRM155R61C474KE01D-datasheet.html QUOTE Tolerance X5R SMT Multilayer Ceramic Capacitor GRM155R60J102KA01D MURATA 0402 1 nF 6.3 V ±10% http://www.searchdatasheet.com/GRM155R60J102KA01D-datasheet.html QUOTE Tolerance X5R SMT Multilayer Ceramic Capacitor GRM155R61C222KA01D MURATA 0402 2.2 nF 16 V ±10% http://www.searchdatasheet.com/GRM155R61C222KA01D-datasheet.html QUOTE Tolerance X5R SMT Multilayer Ceramic Capacitor GRM155R71C102KA01D MURATA 0402 1 nF 16 V ±10% http://www.searchdatasheet.com/GRM155R71C102KA01D-datasheet.html QUOTE Tolerance X7R SMT Multilayer Ceramic Capacitor GRM1885C1H1R5CA01D MURATA 0603 1.5 pF 50 V ±0.25 http://www.searchdatasheet.com/GRM1885C1H1R5CA01D-datasheet.html QUOTE pF Tolerance C0G SMT Multilayer Ceramic Capacitor GRM155R60J334KE01D MURATA 0402 0.33 uF 6.3 V http://www.searchdatasheet.com/GRM155R60J334KE01D-datasheet.html QUOTE ±10% Tolerance X5R SMT Multilayer Ceramic Capacitor GRM155R71H222JA01D MURATA 0402 2.2 nF 50 V ±5% http://www.searchdatasheet.com/GRM155R71H222JA01D-datasheet.html QUOTE Tolerance X7R SMT Multilayer Ceramic Capacitor GRM155R61A103KA01D MURATA 0402 10 nF 10 V ±10% http://www.searchdatasheet.com/GRM155R61A103KA01D-datasheet.html QUOTE Tolerance X5R SMT Multilayer Ceramic -

Avalanche Photodiode a User Guide Understanding Avalanche Photodiode for Improving System Performance

High performance sensors APPLICATION NOTE Avalanche photodiode A User Guide Understanding Avalanche photodiode for improving system performance Introduction Contents Avalanche photodiode detectors (APD) APD structures have and will continue to be used in APD noise many diverse applications such as laser Photon counting technique range finders, data communications or photon correlation studies. This paper discusses APD structures, critical Applications performance parameter and excess noise Light detection factor. Laser range finder For low-light detection in the 200- to Photon counting 1150-nm range, the designer has three Datacomm basic detector choices - the silicon PIN Optical Tomography detector, the silicon avalanche LIDAR photodiode (APD) and the photomultiplier Fluorescence detection tube (PMT). Particle sizing APDs are widely used in instrumentation and aerospace applications, offering a combination of high speed and high sensitivity unmatched by PIN detectors, and quantum efficiencies at >400 nm unmatched by PMTs. www.optoelectronics.perkinelmer.com APPLICATION NOTE Table of Contents What is an Avalange photodiode 3 Selecting an APD 5 Excess Noise Factor 6 Geiger Mode 7 Applications 8 www.optoelectronics.perkinelmer.com Avalanche photodiode 2 APPLICATION NOTE What is an Avalanche Photodiode? APD Structures In order to understand why more than one APD structure exists, it is important to appreciate the design trade-offs that must be accommodated by the APD designer. The ideal APD would have zero dark noise, no excess noise, broad spectral and frequency response, a gain range from 1 to 106 or more, and low cost. More simply, an ideal APD would be a good PIN photodiode with gain! In reality however, this is difficult to achieve because of the need to trade-off conflicting design requirements. -

1. with Schematic Representation Explain the Working Principle of Pin Photo Diode

Optical Communications 1. With schematic representation explain the working principle of pin photo diode. Ans: PIN Photodiode PIN diode consists of an intrinsic semiconductor sandwiched between two heavily doped p-type and n-type semiconductors as shown in Fig. 6.1.1. Sufficient reverse voltage is applied so as to keep intrinsic region free from carriers, so its resistance is high, most of diode voltage appears across it, and the electrical forces are strong within it. The incident photons give up their energy and excite an electron from valance to conduction band. Thus a free electron hole pair is generated, these are called as photo carriers. These carriers are collected across the reverse biased junction resulting in rise in current in external circuit called photocurrent. In the absence of light, PIN photodiodes behave electrically just like an ordinary rectifier diode. If forward biased, they conduct large amount of current. PIN detectors can be operated in two modes, Photovoltaic and photoconductive. In photovoltaic mode, no bias is applied to the detector. In this case the detector works very slow, and output is approximately logarithmic to the input light level. Real world fiber optic receivers never use the photovoltaic mode. In photoconductive mode, the detector is reverse biased. The output in this case is a current that is very linear with the input light power. The intrinsic region somewhat improves the sensitivity of the device. It does not provide internal gain. The combination of different semiconductors operating at different wavelengths allows the selection of material capable of responding to the desired operating wavelength. -

Circuits for High-Efficiency Avalanche-Diode Oscillators

1060 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON MICROWAVE THEORY AND TECHNIQUES, VOL. MTT-17, NO. 12, DECEMBER 1969 Circuits for High-Efficiency Avalanche- Diode Oscillators W. J. EVANS Absfract—This paper describes and analyzes the circuits which have II. THE TRAPATT MODE been used successfully for TRAPATT oscillator studies. The results lead In order to understand the operation of high-efficiency to a better understanding of the TRAPATT oscillator and yield a simple model of the oscillator which is useful for circuit design. oscillators, it is necessary to understand what happens when The circuit characteristics of ms experimental TRAPATT oscillator large RF voltage swings exist across an IMPATT diode. are determined from measurements on the circuits and from equivalent Therefore, this section will begin with a review of the large- circuit model calculations. The following conclusions can be drawn from signal behavior of an IMPATT oscillator. the analysis. First, the avalanche diode requires sufficient capacitance near Fig. l(a) is a plot of the field profile and carrier densities the diode to sustain the high-current state required for TRAPATT oper- in an oscillating IMPATT diode at a particular point in ation. Seeondly, at a distance from the diode corresponding to approx. time. The profile shown here is for a 6-GHz n+-p-p+ epi- inmtely one half-wavelength at the TRAPATT frequency the transmission taxial germanium diode [4]. The plots are made for the par- ~me containing the diode should be terminated by a low-pass filter. The ticular point in the RF voltage and current waveforms indi- function of the filter is to pass the TRAPATT frequency and to provide a cated by the squares in Fig. -

Noise in Avalanche Transit-Time Devices

1674 PROCEEDINGS OF THE IEEE, VOL. 59, NO. 12, DECEMBER 1971 for receiving arrays,” ZEEE Trans. Antennas Propagat. (Commun.), [22] C. J. Drane, Jr., and J. F. McIlvenna, “Gain maximization and VO~.AP-14, NOV.1966, pp. 792-794. controlled null placement simultaneously achievedin aerial array [9] A. I. Uzkov, ‘‘An approach to the problem of optimum directive patterns,” Air Force Cambridge Res. Labs., Bedford,Mass., antenna design,” C. R. Acad. Sci. USSR., vol. 35, 1946, p. 35. Rep. AFCRL-69-0257, June 1969. [lo] A. Bloch, R. G. Medhurst, and S. D. Pool, “A new approach to [23] R. F. Hamngton, “Matrixmethods for field problems,” Proc. the design of superdirective aerial arrays,” Proc. Znst. Elec. Eng., ZEEE, vol. 55, Feb. 1967, pp. 136-149. VO~.100, Sept. 1953, pp. 303-314. [24] J. A. Cummins,“Analysis of a circulararray of antennas by [ll] M.Uzsoky and L. Solymar,“Theory of superdirectivelinear matrix methods,” Ph.D. dissertation, Elec. Eng. Dept., Syracuse arrays,” Acta Phys. (Budapt), vol. 6, 1956, pp. 185-204. University, Syracuse,N. Y., Dec. 1968. [12] C. T. Tai, “The optimum directivity of uniformly spaced broad- [25] B. J. Strait and K. Hirasawa, “On radiation and scattering from sidearrays ofdipoles,” ZEEE Trans. Antennas Propgat., vol. arrays of wire antennas,” Proc. Nut. Elec. Con$, vol. 25, 1969. AP-12, July 1964, pp. 447-454. [26] A.T. Adams and B. J. Strait, “Modernanalysis methods for [13] D. K. Cheng and F. I. Tseng, “Gain optimization for arbitrary EMC,” ZEEEIEMC Symp. Rec., July 1970, pp. 383-393. antenna arrays,’’ ZEEE Trans. -

FAGOR Avalanche Rectifiers

Application Note Fagor Electrónica Semiconductores Avalanche Rectifiers Avalanche Rectifiers are diodes that can tolerate voltages above the repetitive reverse maximum blocking voltage (Vrrm) and, furthermore, dissipate a specified maximum energy during these pulses. Here we describe how these diodes differ from normal rectifiers and the applications to which they are suited. Introduction Rectifiers are two-terminal devices that are used to conduct current in one direction but block in the other according to a characteristic of the type shown in Figure 1. Standard rectifiers operate stably in either the Reverse Blocking Mode or in the Forward Conducting Mode. In the first case, only a very small leakage current flows so that power dissipation in the device is not important. In the second case, the forward voltage is more than a volt so considerable power may be dissipated in the device, but provided the heat is extracted efficiently the junction temperature will not exceed the maximum rated value and the device will be stable. I Figure 1 Modes of Operation within the I-V characteristic of Rectifiers. V Forward Concucting Avalanche Reverse Blocking Mode Mode Mode Further limitations apply when the rectifier is switched from conducting a large forward current to blocking a large reverse voltage. During a time after switching, the current that flows in the reverse direction greatly exceeds the reverse leakage value. Even if the delay in establishing the blocking condition is not important in the application, the additional power dissipated may cause the device to overheat and eventually fail. The recovery time depends strongly on the forward current before switching but standard conditions have been established to measure the Trr parameter (Typically: I F=0.5A switched to I R=1A at t=0 and recuperation defined has having occurred when I R=0.25A).