Designing with Publics That Are Already Busy: a Case from Denmark Andreas Birkbak, Morten Krogh Petersen, Tobias Bornakke Jørgensen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of German-Scandinavian Relations

A History of German – Scandinavian Relations A History of German-Scandinavian Relations By Raimund Wolfert A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Raimund Wolfert 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Table of contents 1. The Rise and Fall of the Hanseatic League.............................................................5 2. The Thirty Years’ War............................................................................................11 3. Prussia en route to becoming a Great Power........................................................15 4. After the Napoleonic Wars.....................................................................................18 5. The German Empire..............................................................................................23 6. The Interwar Period...............................................................................................29 7. The Aftermath of War............................................................................................33 First version 12/2006 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations This essay contemplates the history of German-Scandinavian relations from the Hanseatic period through to the present day, focussing upon the Berlin- Brandenburg region and the northeastern part of Germany that lies to the south of the Baltic Sea. A geographic area whose topography has been shaped by the great Scandinavian glacier of the Vistula ice age from 20000 BC to 13 000 BC will thus be reflected upon. According to the linguistic usage of the term -

Apostolic Discourse and Christian Identity in Anglo-Saxon Literature

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship Repository APOSTOLIC DISCOURSE AND CHRISTIAN IDENTITY IN ANGLO-SAXON LITERATURE BY SHANNON NYCOLE GODLOVE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2010 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Charles D. Wright, Chair Associate Professor Renée Trilling Associate Professor Robert W. Barrett Professor Emerita Marianne Kalinke ii ABSTRACT “Apostolic Discourse and Christian Identity in Anglo-Saxon Literature” argues that Anglo-Saxon religious writers used traditions about the apostles to inspire and interpret their peoples’ own missionary ambitions abroad, to represent England itself as a center of religious authority, and to articulate a particular conception of inspired authorship. This study traces the formation and adaptation of apostolic discourse (a shared but evolving language based on biblical and literary models) through a series of Latin and vernacular works including the letters of Boniface, the early vitae of the Anglo- Saxon missionary saints, the Old English poetry of Cynewulf, and the anonymous poem Andreas. This study demonstrates how Anglo-Saxon authors appropriated the experiences and the authority of the apostles to fashion Christian identities for members of the emerging English church in the seventh and eighth centuries, and for vernacular religious poets and their readers in the later Anglo-Saxon period. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to many people for their help and support throughout the duration of this dissertation project. -

America Letter Fall 2007/Winter 2008 Vol

America Letter Fall 2007/Winter 2008 Vol. XXI, No. 1 Your Museum in the An International THE DANISH IMMIGRANT MUSEUM Her Majesty Queen Margrethe II of Denmark, Protector Heart of the Continent Cultural Center ® Member of the American Association of Museums BOX 470 • ELK HORN, IOWA 51531 Across Oceans, Across Time, Across Generations®: The Nybys By Eva Nielsen “You’ll never amount to anything.” That’s what Folmer Nyby was told. He laughs about the comment now. And why shouldn’t he? Folmer immigrated to the United States as a 19-year- old in 1950 carrying only a suitcase and plans to marry Vera Lodahl, a second generation Dane from Dagmar, Montana. They married. They built several success- ful businesses. They raised three children. They have grandchildren, even great-grandchildren. They enjoy Folmer and Vera Nyby met in Denmark in 1948. Vera grew their home by a lake in Indiana. They drive to Arizona up in Dagmar, Montana, the daughter of Danish immigrant for the winter. And, then, the Nybys spend time at their parents. While visiting Denmark, she met Folmer at a dance in his hometown of Vestervig. The picture of Vera was taken summer home in Denmark—just down the road from in Denmark in 1948 so that Folmer could have it when she Vestervig, the town where Folmer was born. returned home to the United States. Folmer was just 13-years-old when he fi nished school to anything.’ I’ll tell you, when somebody tells you that and was confi rmed in the Vestervig church. In 1944—at when you’re young…you build in something in yourself age 14—he began his professional career as an apprentice that says I’ll show him.” Then Folmer adds, “I’ll betcha in a grocery it was good for me; it gave me a drive.” store. -

Andreas Wormser, Immigrant Locator and Land Developer

Building castles in the air : Andreas Wormser, immigrant locator and land developer by Delbert Delos Van Den Berg A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Montana State University © Copyright by Delbert Delos Van Den Berg (1996) Abstract: Andrew Wormser was the father of Dutch communities in southwestern Montana, and his promotion of immigrant settlement in the West contributed to the establishment of Dutch communities throughout the Intermountain area. Transformed from an idealistic missionary into a immigrant locator and pioneer real estate developer, Andrew's colonization attempts were choreographed by his family's heritage, and complicated by a lifestyle that created illusions of grandeur. Andrew attempted to secure a place in America's upper class by creating a personal fortune from his development schemes in Montana, but he failed to achieve his goals when he disregarded the economic and environmental realities of the frontier. Andrew's failed development schemes, however, are turned into a success when his dream of empire is redefined as a lasting imprint on the human and physical landscape of the Intermountain West. My research of Andrew Wormser's life and entrepreneurial activities consisted of an analysis of archival material, government documents, primary and secondary sources, personal interviews, and on site visits to Wormser City and Big Timber, Montana, and Wenatchee, Washington. The Montana Historical Society Library; Merrill G. Burlingame Special Collections at Montana State University, Bozeman; Hope College Archives and the Heritage Collection, Holland, MI; and Heritage Hall and Colonial Origins Collection of the Christian Reformed Church, Calvin College, Grand Rapids, MI, proved very valuable to my research. -

Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED)

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 9/13/2021 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan FMO Inna Rotenberg ICASS Chair CDR David Millner IMO Cem Asci KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, ISO Aaron Smith Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: https://af.usembassy.gov/ Algeria Officer Name DCM OMS Melisa Woolfolk ALGIERS (E) 5, Chemin Cheikh Bachir Ibrahimi, +213 (770) 08- ALT DIR Tina Dooley-Jones 2000, Fax +213 (23) 47-1781, Workweek: Sun - Thurs 08:00-17:00, CM OMS Bonnie Anglov Website: https://dz.usembassy.gov/ Co-CLO Lilliana Gonzalez Officer Name FM Michael Itinger DCM OMS Allie Hutton HRO Geoff Nyhart FCS Michele Smith INL Patrick Tanimura FM David Treleaven LEGAT James Bolden HRO TDY Ellen Langston MGT Ben Dille MGT Kristin Rockwood POL/ECON Richard Reiter MLO/ODC Andrew Bergman SDO/DATT COL Erik Bauer POL/ECON Roselyn Ramos TREAS Julie Malec SDO/DATT Christopher D'Amico AMB Chargé Ross L Wilson AMB Chargé Gautam Rana CG Ben Ousley Naseman CON Jeffrey Gringer DCM Ian McCary DCM Acting DCM Eric Barbee PAO Daniel Mattern PAO Eric Barbee GSO GSO William Hunt GSO TDY Neil Richter RSO Fernando Matus RSO Gregg Geerdes CLO Christine Peterson AGR Justina Torry DEA Edward (Joe) Kipp CLO Ikram McRiffey FMO Maureen Danzot FMO Aamer Khan IMO Jaime Scarpatti ICASS Chair Jeffrey Gringer IMO Daniel Sweet Albania Angola TIRANA (E) Rruga Stavro Vinjau 14, +355-4-224-7285, Fax +355-4- 223-2222, Workweek: Monday-Friday, 8:00am-4:30 pm. -

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research Name Abreviations Nicknames Synonyms Irish Latin Abigail Abig Ab, Abbie, Abby, Aby, Bina, Debbie, Gail, Abina, Deborah, Gobinet, Dora Abaigeal, Abaigh, Abigeal, Gobnata Gubbie, Gubby, Libby, Nabby, Webbie Gobnait Abraham Ab, Abm, Abr, Abe, Abby, Bram Abram Abraham Abrahame Abra, Abrm Adam Ad, Ade, Edie Adhamh Adamus Agnes Agn Aggie, Aggy, Ann, Annot, Assie, Inez, Nancy, Annais, Anneyce, Annis, Annys, Aigneis, Mor, Oonagh, Agna, Agneta, Agnetis, Agnus, Una Nanny, Nessa, Nessie, Senga, Taggett, Taggy Nancy, Una, Unity, Uny, Winifred Una Aidan Aedan, Edan, Mogue, Moses Aodh, Aodhan, Mogue Aedannus, Edanus, Maodhog Ailbhe Elli, Elly Ailbhe Aileen Allie, Eily, Ellie, Helen, Lena, Nel, Nellie, Nelly Eileen, Ellen, Eveleen, Evelyn Eibhilin, Eibhlin Helena Albert Alb, Albt A, Ab, Al, Albie, Albin, Alby, Alvy, Bert, Bertie, Bird,Elvis Ailbe, Ailbhe, Beirichtir Ailbertus, Alberti, Albertus Burt, Elbert Alberta Abertina, Albertine, Allie, Aubrey, Bert, Roberta Alberta Berta, Bertha, Bertie Alexander Aler, Alexr, Al, Ala, Alec, Ales, Alex, Alick, Allister, Andi, Alaster, Alistair, Sander Alasdair, Alastar, Alsander, Alexander Alr, Alx, Alxr Ec, Eleck, Ellick, Lex, Sandy, Xandra, Zander Alusdar, Alusdrann, Saunder Alfred Alf, Alfd Al, Alf, Alfie, Fred, Freddie, Freddy Albert, Alured, Alvery, Avery Ailfrid Alberedus, Alfredus, Aluredus Alice Alc Ailse, Aisley, Alcy, Alica, Alley, Allie, Allison, Alicia, Alyssa, Eileen, Ellen Ailis, Ailise, Aislinn, Alis, Alechea, Alecia, Alesia, Aleysia, Alicia, Alitia Ally, -

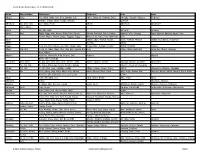

Name Born Died Burial Location Other Information

NAME BORN DIED BURIAL OTHER INFORMATION LOCATION • AAGREU, Christina Nov. 16 July 23, 1892 Born in Denmark Ada 1881 1881 Plot 8 / ALLEN, Elizabeth H. Feb. 2,1805 Oct. 11,1885 Plot 5 > ALLRED, Eliza E. Apr. 14,1864 Oct. 26,1881 Plot 11 Daughter of Karen M.S. Allred / ALLRED, George M. Sept. 27,1837 Jan. 14,1926 Plot 11 Pvt UT Ter Mil Cav,Blackhawk War born Illinois / ALLRED, Ira Pratt Nov. 30, 1896 Nov. 11, 1896 Parents: Orsen & Hannah/died of cough - / ALLRED, Isaac June 26, 1811 May 12, 1859 Killed in Mount Pleasant during argumen over the feed bill of a sheep. ALLRED, James W. May5, 1873 Oct. 22, 1948 Plot 11 Born in Ephraim, a wagoner in Spanish / American War / ALLRED, Karen M.S. Jan. 9,1842 Apr. 16,1892 Plot 11 Born in Lasby, Aarhus, Denmark / ALLRED, Parley Oct. 4,1876 May 16,1882 Plot 11 Son of Karen M.S, Allred / ANDERSEN, Ammon Sylvester Dec. 1, 1894 Dec. 31, 1894 Parents: Niels & Maria P. / ANDERSEN,Johan Nov. 8,1818 Jan. 21, 1863 Plot 17 Born in Sweden / ANDERSEN, Laurence H. Mar.21, 1883 Jan. 2,1891 Plot 38 / ANDERSON 1877 1879 Plot 18 / ANDERSON, A.P. Bastholin Oct. 18,1825 Oct. 1,1893 Born in Denmark / ANDERSON, Albert L. Feb. 15, 1875 Dec.11,1890 Parents: Andrew & Stena / ANDERSON, Ana C. June 20,1832 Sept. 16, 1916 Plot 43 Wife of H. Hansen / ANDERSON, Ana Marie Aprill2,1839 Aug. 8,1882 Plot 4 ANDERSON, Andrew Christian Oct. 16,1863 Feb. 19,1865 Parents: Jens Peter & Rebecca Christina /' Friis / ANDERSON, Andrew P. -

Andreas Elpidorou 313 Bingham Humanities, Louisville, Ky 40292 Elpidorou.Net [email protected]

DEPARTMENT PHILOSOPHY • UNIVERSITY OF LOUISVILLE ANDREAS ELPIDOROU 313 BINGHAM HUMANITIES, LOUISVILLE, KY 40292 ELPIDOROU.NET [email protected] E MPLOYMENT 2015- Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, University of Louisville 2013-2015 Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, University of Louisville 2012-2013 Visiting Lecturer, Department of Philosophy, Boston University 2012 Lecturer, Metropolitan College, Boston University EDUCATION 2006-2013 Ph.D., Philosophy, Boston University Dissertation title: “On Sensible Matters: A Defense of Conceptual Dualism” 2009-2010 Visiting Scholar, University of Pittsburgh (Department of Philosophy) 2002-2006 B.S. in Physics (High Distinction), University of Virginia SPECIALIZATION AOS Philosophy of Mind, Metaphysics, Phenomenology AOC Philosophy of Psychology and Cognitive Science, Epistemology, History of Philosophy PUBLICATIONS MONOGRAPHS forthcoming Physicalism and the Spell of Consciousness (under contract). New York: Routledge. EDITED BOOKS & JOURNAL ISSUES forthcoming “The Character of Physicalism.” Special Issue of Topoi. 2015 Philosophy of Mind and Phenomenology (co-edited with D. Dahlstrom and W. Hopp), New York: Routledge. 2014 “The Phenomenology and Science of Emotions.” Special Issue of Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 13 (4). (Guest co-editor with L. Freeman) JOURNAL ARTICLES forthcoming “The Character of Physicalism.” Topoi. in press “Embodied Conceivability: How to Keep the Phenomenal Concept Strategy Grounded” (with G. Dove) Mind & Language. in press “Seeing the Impossible.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. In press “A Posteriori Physicalism and Introspection.” Pacific Philosophical Quarterly. DOI: 10.1111/papq.12068. in press “Affectivity in Heidegger II: Temporality, Boredom, and Beyond” (with L. Freeman). Philosophy Compass. in press “Affectivity in Heidegger I: Moods and Emotions in Being and Time” (with L. -

Blurring the Lines: Private and Public Dissection in Renaissance Italy

University of Nevada, Reno Blurring the Lines: Private and Public Dissection in Renaissance Italy A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of History By Kalina Yamboliev Dr. Bruce Moran, Thesis Advisor May, 2010 UNIVERSITY THE HONORS PROGRAM OF NEVADA RENO We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by KALINA YAMBOLIEV entitled Blurring the Lines: Private and Public Dissection in Renaissance Italy Be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF HISTORY _________________________________________________ Dr. Bruce Moran, Department of History; Faculty Mentor _________________________________________________ Tamara Valentine, Director; Honors Program i -Abstract- From the fourteenth through the eighteenth century in Europe human dissection came to be practiced for a variety of purposes. Private dissections, in the forms of judicial, holy, and maternal anatomies, were performed, respectively, for the purposes of generating medical evidence that could be used in court, finding markings inside of a holy individual’s body that would confirm his or her sainthood, and to diagnose diseases which could have negative implications for the future of a family. Public dissections, on the other hand, were performed in university settings as a demonstrative and didactic technique, as well as a sort of public spectacle to gain attention and prestige for the institution hosting the event. This paper will delve deeper into these varieties of dissection, both public and private, as well as the extents to which they intersected and worked together to build off of one another. The final part of the paper will also consider an important anatomical figure – Andreas Vesalius – who performed anatomical work both privately and publically and who, with the publishing of his famous anatomical text De humani corporis fabrica in 1543, revolutionized medical and anatomical practice forever. -

April 22, 1989 Official Talks Between Todor Zhivkov and Andreas Papandreou, Prime Minister of Greece

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified April 22, 1989 Official talks between Todor Zhivkov and Andreas Papandreou, Prime Minister of Greece Citation: “Official talks between Todor Zhivkov and Andreas Papandreou, Prime Minister of Greece,” April 22, 1989, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Central State Archive, Sofia, Fond 1-B, Record 60, File 414. Translated by Assistant Professor Kalina Bratanova. Edited by Dr. Jordan Baev, Momchil Metodiev, and Nancy L. Meyers. Obtained by the Bulgarian Cold War Research Group. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/112045 Summary: Official talks between the President of the State Council of the People’s Republic of Bulgaria Todor Zhivkov and the Prime Minister of Greece Andreas Papandreou regarding Greek-Bulgarian relations. Original Language: Bulgarian Contents: English Translation Scan of Original Document OFFICIAL TALKS Between the President of the State Council of the People's Republic of Bulgaria Todor Zhivkov and the Prime Minister of Greece Andreas Papandreou[1] 22 April 1989, Alexandroupolis[2] ANDREAS PAPANDREOU: I once again have the chance to welcome our country's friend Todor Zhivkov and his assistants. I hope that the warmth with which residents of Alexandroupolis welcomed you is indicative of our people's feelings towards you. I guess that our meetings are of a more specific nature this time; today the meeting is taking place on our territory, the next will take place on your territory. I believe that we will have enough time to discuss important issues during our talks. It is true that we share a common view on topics related to the preservation of world peace, the situation in the Balkans, and understanding between the Balkan countries. -

The Composite Nature of Andreas

Article The Composite Nature of Andreas David Maddock Department of Language and Literature, Signum University, Nashua, NH 03063, USA; [email protected] Received: 7 May 2019; Accepted: 20 July 2019; Published: 31 July 2019 Abstract: Scholars of the Old English poem Andreas have long debated its dating and authorship, as the poem shares affinities both with Beowulf and the signed poems of Cynewulf. Although this debate hinges on poetic style and other internal evidence, the stylistic uniformity of Andreas has not been suitably demonstrated. This paper investigates this question by examining the distribution of oral-formulaic data within the poem, which is then correlated to word frequency and orthographic profiles generated with lexomic techniques. The analysis identifies an earlier version of the poem, which has been expanded by a later poet. Keywords: Anglo-Saxon literature; Old English language; philology; digital humanities; medieval studies; Andreas; Cynewulf; Beowulf; lexomics 1. Introduction Cynewulf has received scrutiny as one of the few named poets in the Anglo-Saxon vernacular due to the existence of four poems—Elene, Juliana, Christ II, and The Fates of the Apostles—that contain rune signatures bearing his name. The modern expectation is for an author to sign his work, but because manuscript collections of Anglo-Saxon poetry appear to have been intended for local audiences this was not the norm in medieval England (Bredehoft 2009, p. 45). Cynewulf signed these poems to solicit prayers on his behalf, not due to an expectation of publication (p. 46). Due to the anonymous nature of the Old English poetic corpus, unsigned poems authored by Cynewulf may exist, but because we know so little about his biography, “the whole question of Cynewulf’s authorship is intimately tied up with the issue of style” (Orchard 2003, p. -

PISA 2018 Insights and Interpretations

2 018 Insights and Interpretations Andreas Schleicher PISA 2018: Insights and Interpretations Equipping citizens with the knowledge and skills necessary to achieve their full potential, to contribute to an increasingly interconnected world, and to convert better skills into better lives “needs to become a more central preoccupation of policy makers around the world. Fairness, integrity and inclusiveness in public policy thus all hinge on the skills of citizens. In working to About PISA achieve these goals, more and more countries are Up to the end of the 1990s, the OECD’s comparisons might remember enough to follow in our footsteps; of education outcomes were mainly based on but if they learn how to learn, and are able to think looking beyond their own borders for evidence measures of years of schooling, which are not reliable for themselves, and work with others, they can go indicators of what people actually know and can do. anywhere they want. of the most successful and efficient education The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) changed this. The idea behind PISA lay in Some people argued that the PISA tests are unfair, policies and practices. testing the knowledge and skills of students directly, because they may confront students with problems they through a metric that was internationally agreed upon; have not encountered in school. But then life is unfair, linking that with data from students, teachers, schools because the real test in life is not whether we can PISA is not only the world’s most comprehensive and systems to understand performance differences; remember what we learned at school, but whether we and then harnessing the power of collaboration to will be able to solve problems that we can’t possibly anticipate today.