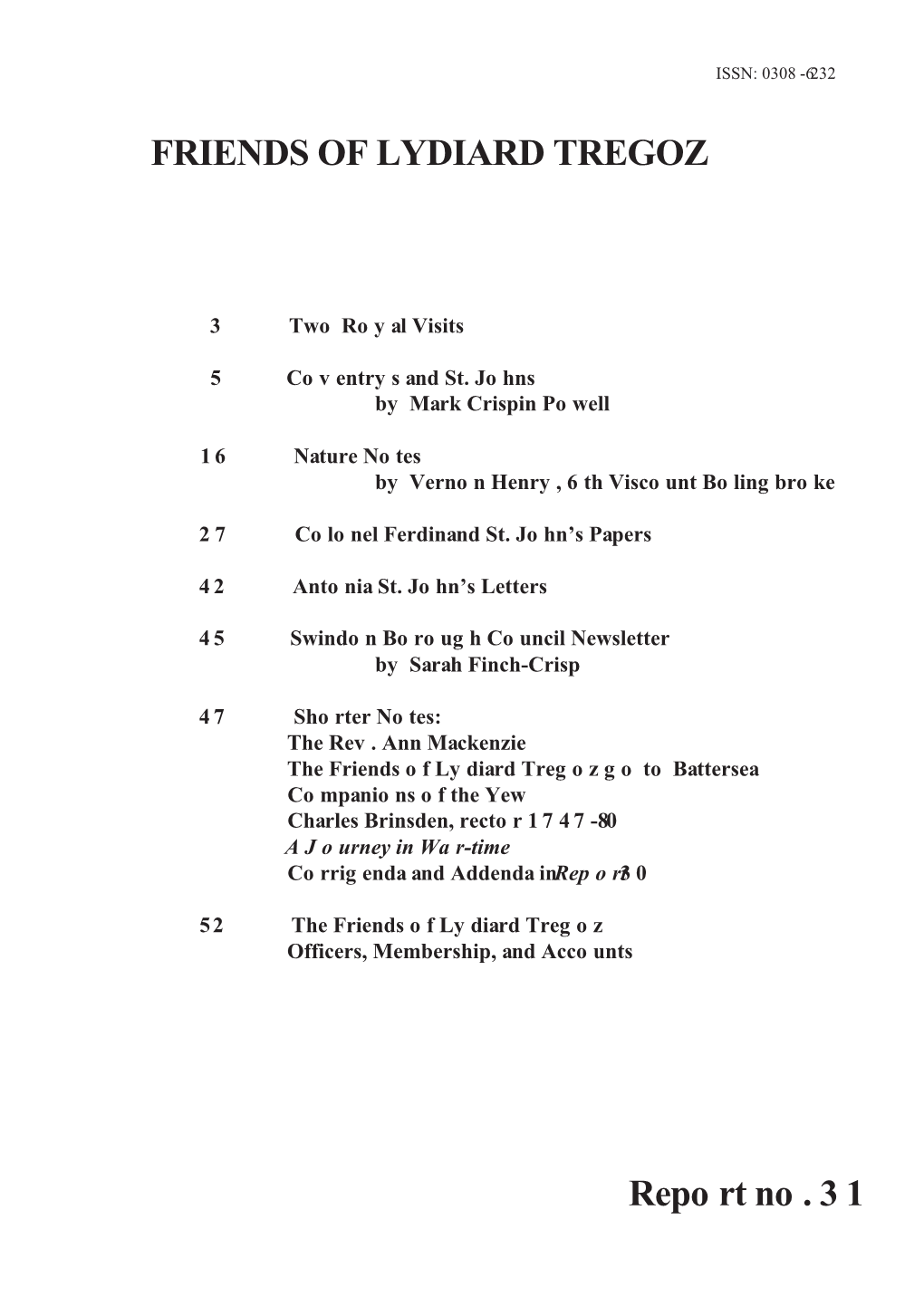

FRIENDS of LYDIARD TREGOZ Report No. 31

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Services & Music

S ERVICES & M USIC August 2017 ~ July 2018 Sunday 30 July Choir in Residence Today Seventh Sunday after Trinity St Peter’s, Earley 7.40am Morning Prayer BERKELEY CHAPEL 8.00am Holy Communion (BCP) QUIRE 10.00am CATHEDRAL EUCHARIST NAVE Preacher Canon Professor Martin Gainsborough Setting Darke in F Psalm 105.1-11 Motet O king all glorious, Willan Hymns Processional 440 Lobe den Herren [omit v.5] Offertory 238 Melcombe Communion 276 Bread of heaven Post-communion 391 Gwalchmai Voluntary Voluntary in D – Croft 3.30pm CHORAL EVENSONG QUIRE Preacher The Dean Responses Ayleward Psalm 75 Canticles Wood in E flat (No.1) Anthem Save us, O Lord – Bairstow Hymns 431 Hereford; 239 Slane Voluntary Prelude in a – Krebs Monday 31 July Choir in Residence Today Ignatius of Loyola, Founder of the Society of Jesus, 1556 St Mark’s Episcopal Church Berkeley, CA, USA 8.30am Morning Prayer BERKELEY CHAPEL 12.30pm Eucharist ELDER LADY CHAPEL 5.15pm CHORAL EVENSONG QUIRE Responses Bounemani Psalm 146 Canticles Friedell in F Hymn 456 Sandys Anthem Lass dich nur nichts nicht dauren – Brahms Tuesday 1 August Choir in Residence Today Feria St Mark’s Episcopal Church, Berkeley, CA, USA 8.30am Morning Prayer BERKELEY CHAPEL 12.30pm Eucharist SEAFARERS’ CHAPEL 1.15pm LUNCHTIME RECITAL NAVE Untune the Sky – Oxford-based Vocal Consort 5.15pm CHORAL EVENSONG QUIRE Responses Bounemani Psalm 6 Canticles All Saints Evening Service – Hirten Hymn 485 Thornbury Anthem Perfect love casteth out fear – Southwood 2 bristol-cathedral.co.uk Wednesday 2 August Choir in Residence Today -

The Enthronement of the 56Th Bishop of Bristol

The Enthronement of THE RIGHT REV EREND VIVIENNE FAULL th The 56 Bishop of Bristol in her Cathedral Church of the Holy and Undivided Trinity, Bristol THE SERVICE AT WHICH THE NEW BISHOP IS WELCOMED INTO THE DIOCESE Saturday 20 October, 2018, 2.30pm THE DEAN’S WELCOME Welcome to your Cathedral Church. The first Bishop of Bristol, Paul Bush, was consecrated on 25 June 1542 and came to a monastery that had been deserted for two years, newly made a Cathedral. The demands of city and diocese were too much for a reclusive scholar and he quickly withdrew to his manor at Abbots Leigh. At her consecration, Bishop Viv was reminded that bishops lead us, knowing their people and being known by them. Before this service began she was met in the heart of the city by its people. In this service you will hear again and again +Viv’s resolution to be servant of diocese and city and to be with us. Successive bishops have been great friends and supporters of their Cathedral Church. Robert Wright raised huge sums for repairs and a new organ in 1630. At other times, the relationship between bishop and Cathedral has been more difficult. In the eighteenth century Bishop Newton despaired of his absent dean. Today, we rejoice in the fact that the Cathedral is the Bishop’s Church. When +Viv knocks, three times, at the great west door and waits for entry, we will act out the fact that she recognises the Cathedral has a life and ministry of its own and yet is also hers. -

St Mary's Stoke Bishop Parish Profile

St Mary's Stoke Bishop Parish Profile Page &1 Contents From the Bishop 3 Welcome to St Mary’s 4 St Mary’s in a nutshell 5 Avonside Mission Area 6 History and location 8 St Mary’s is for everyone - our culture and styles of worship 9 Youth and Children 10 Stoke Bishop Church of England Primary school 11 Discipleship 12 Outreach and Mission 13 Prayer and Pastoral Care 14 Buildings 15 Facts and Figures 16 Finances 16 Stewardship 17 Statistics 17 Who we are 18 Consultation Feedback 19 Role Description 21 Person Specification 25 The Diocese of Bristol 28 Find us 29 Contacts 29 Appendix 1 Avonside Mission Area Overview 30 Appendix 2 ASMA Statistics 31 Appendix 3 St Mary’s Organisational Chart and Ministry teams 32 Page &2 From the Bishop April 2019 Thank you so much for taking the time to discern whether joining us here in Bristol Diocese might be the next stage of your ministerial journey and whether your gifts match the exciting opportunity that this vacancy at St Mary’s Stoke Bishop represents. The Diocese of Bristol’s commitment to making connections with God, with each other and with our communities, and to the development of Mission Areas, has become part of the life of St Mary’s, evidenced by its generous support of the developing life of the Avonside Mission Area. Key leaders from this initiative are accountable to the Diocesan Mission Programme Board to enable lessons in church growth to be learnt for the benefit of all. The task of the next incumbent will include the development of the life of the parish alongside this wider commitment. -

CHURCH of IRELAND PRESS OFFICE Church of Ireland House, 61 – 67 Donegall Street, Belfast BT1 2QH

CHURCH OF IRELAND PRESS OFFICE Church of Ireland House, 61 – 67 Donegall Street, Belfast BT1 2QH www.ireland.anglican.org http://twitter.com/churchofireland Tuesday 17 July 2012 From The Most Revd Alan Harper, Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland and co-signatories as listed: Dear Secretary General, We refer to the continuing plight of the residents of Camp Ashraf/Liberty and wish to express deepening concern about the worsening humanitarian situation confronting many defenceless people. We are particularly alarmed by recent reports of a press conference recently held by high ranking officials of the State Department of the United States of America in which it appeared that the residents of Ashraf and the leadership of the PMOI were threatened with armed intervention risking a potential massacre on or after July 20 2012. We strongly condemn the threat of force or the use of force directed towards the people of Camp Ashraf whose status as refugees has been recognised by the United Nations. We therefore call upon you, Secretary General, and Secretary of State Clinton immediately to intervene. Iraq must be pressed to abide by its international obligations and accord full respect to the human rights of Iranian refugees in Iraq. It is wholly inappropriate to blame the victims of oppression for the crimes of their oppressors as appears to be the position adopted by the two high ranking US officials. We note that a similar rationale was offered for the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, on the grounds that it is appropriate that one man should die on behalf of the people. -

The London Gazette of Monday, 28Th June 1976 Bp

No. 46947 8989 SUPPLEMENT TO The London Gazette of Monday, 28th June 1976 bp Registered as a Newspaper TUESDAY, 29ra JUNE 1976 MINISTRY OF DEFENCE ARMY DEPARTMENT Short Serv. Commit. 2nd Lt. The Duke of ROXBURGHE (498248) to be Lt., 29th June 1976. 29th Jun. 1976. Gen. Sir Roland GIBBS, G.C.B., C.B.E., D.S.O., M.C., ROYAL ARMOURED CORPS (114083) Colonel Commandant, 2nd Battalion The Royal Green Jackets, Colonel Commandant, The Parachute REGULAR ARMY Regiment is appointed Aide-de-Camp General to The The undermentioned 2nd Lts. to be Lts., 29th Jun. QUEEN, 25th Jun. 1976, in succession to Gen. Sir Cecil 1976: % BLACKER, G.C.B., O.B.E., M.C. (67083) Colonel, 5th J. S. BLACKETT (498143) 15/19 H. Royal Inniskilling Dragoon Guards, Colonel Com- L. DUCKWORTH (497406) 5 INNIS. D.G. mandant, Corps of Royal Military Police, Colonel Com- J. R. LEMON (498174) R.T.R. mandant, Army Physical Training Corps, tenure expired. S. R. LOGAN (498175) R.T.R. Special Reg. Commits. COMMANDS AND STAFF 2nd Lt. G. R. A. POTTER (498185) 5 INNIS. D.G. to be REGULAR ARMY Lt., 29th Jun. 1976. Gen. Sir Cecil BLACKER, G.C.B., O.B.E., M.C., 2nd Lt. R. C. SUTTON (498201) 4/7 D.G. to be Lt., (67083) late R.A.C. relinquishes the appointment of 29th Jun. 1976. Adjutant-General, Ministry of Defence,. 25th Jun. 1976. Short Serv. Commits. Lt.-Gen. (Local Gen.) Sir Edwin BRAMALL, K.C.B., The undermentioned 2nd Lts. to be Lts., 29th Jun. -

Aldenhamiana No 23 October 2001

Aldenhamiana No 23 October 2001 Published byTHE OLD ALDENHAMIAN SOCIETY Aldenham School, Elstree, Hertfordshire WD6 3AJ, England e-mail: [email protected] www.oldaldenhamian.org ______________________________________________________________________________ THE PRESIDENT'S LETTER Finally, I must send the thanks of the Society to Lindy Creedy who served us so well for many years, and welcome in her place Molly I find myself writing this letter in the aftermath of the horrendous Barton whose husband, Trevor, has most helpfully taken over as Editor terrorist attacks on the United States on 11th September which, in turn, of Aldenhamiana. led to the postponement of the Society’s Committee Meeting which was eventually held a week later than intended, on 18th September. I hope to see many of you at the events that are now being arranged for the months ahead. Dick Vincent That delayed meeting of your Committee considered some of the more significant business in recent years on behalf of active and interested OAs, including the recommended revision of our membership and EDITOR’S NOTES subscription arrangements, which will be put to the next AGM for formal approval in Tallow Chandlers Hall, London, at 5.00pm on 9th This is my first edition of Aldenhamiana as Editor. For those of you April 2002. who do not know me, I was in Kennedy’s House from 1971 to 1975, went to University, spent ten years in the Royal Navy and, after 9th April 2002 will also mark precisely the centenary of the formation changing career and some years living abroad, have now moved back of the OA Society and at our recent Committee meeting we agreed a with my family to live locally and to work in London. -

A RDR Spring 2001

Common Worship THE Services and Prayers for the Church of England Beautifully bound in a range of attractive colours and READER printed in black and red ink on a high quality cream paper,this standard edition is not only a treasure to start using immediately but a personal memento that will go on giving pleasure for years. Recommended retail prices range from £15 to £50. Available from all good bookshops. For more details of Common Worship, please see www.commonworship.com Official and complementary materials available now Official and complementary materials available THE HOUSE OF VANHEEMS LTD Established 1793 St Martin Vestment Ltd READERS’ ROBES Lutton, Near Spalding, Lincs PE12 9LR Excellent quality, cut and tailoring at the Tel/Fax 01406 362386 most reasonable prices or over 25 years our workshop has been Double breasted cassock producing individually made church regalia £115.00 F for churches and cathedrals at home and abroad. Ripon Surplice £48.00 The firm remains in the hands of a clergy family but is managed by Mrs Dorothea Butcher who Reader Blue Scarf will be pleased to discuss £39.00 your requirements. Send for details and D Please telephone or fabric samples. E C F write for further details B and measurement form Cassocks for Readers G L are supplied at prices A Broomfield Works ranging from £71 to Broomfield Place considerably more. Ealing London W13 9LB Tel: 020-8567-7885 THE READER In all things thee to see Spring 2001 Volume 98 No.1 £1.75 Faith House Bookshop BOOKS 7 Tufton Street London SW1P 3QN CDS Tel 020 7222 6952 Fax 020 7976 7180 ICONS DEVOTIONAL Website: www.faithhousebookshop.co.uk MATERIALS e-mail: [email protected] Lent and Easter We carry a wide range of Lent courses, Paschal Candles, Palm Crosses and Church Requisites.We also stock Icons that show the major events of the Easter story. -

House of Lords Official Report

Vol. 716 Thursday No. 25 14 January 2010 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) HOUSE OF LORDS OFFICIAL REPORT ORDER OF BUSINESS Questions Transport: Mobile Telephones Intercept Evidence Honour-related Violence Universities: Finance Questions to the Secretary of State for Transport Buses Aviation: Climate Change Railways: Passenger Satisfaction Business of the House Timing of Debates Business of the House Motion on Standing Orders Child Poverty Bill Order of Consideration Motion Climate Change: Copenhagen Conference Debate UK: Tolerance, Democracy and Openness Debate Marriage (Wales) Bill [HL] Order of Commitment Discharged Co-operative and Community Benefit Societies and Credit Unions Bill [HL] Third Reading General and Specialist Medical Practice (Education, Training and Qualifications) Order 2010 Motion to Approve Written Statements Written Answers For column numbers see back page £3·50 Lords wishing to be supplied with these Daily Reports should give notice to this effect to the Printed Paper Office. The bound volumes also will be sent to those Peers who similarly notify their wish to receive them. No proofs of Daily Reports are provided. Corrections for the bound volume which Lords wish to suggest to the report of their speeches should be clearly indicated in a copy of the Daily Report, which, with the column numbers concerned shown on the front cover, should be sent to the Editor of Debates, House of Lords, within 14 days of the date of the Daily Report. This issue of the Official Report is also available on the Internet at www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld200910/ldhansrd/index/100114.html PRICES AND SUBSCRIPTION RATES DAILY PARTS Single copies: Commons, £5; Lords £3·50 Annual subscriptions: Commons, £865; Lords £525 WEEKLY HANSARD Single copies: Commons, £12; Lords £6 Annual subscriptions: Commons, £440; Lords £255 Index—Single copies: Commons, £6·80—published every three weeks Annual subscriptions: Commons, £125; Lords, £65. -

Royal Engineers Journal

ISSN 0035-8878 THE ROYAL ENGINEERS JOURNAL INSTITUTION OF RE OFFICE COPY DO NOT REMOVE Volume 95 JUNE 1981 No. 2 THE COUNCIL OF THE INSTITUTION OF ROYAL ENGINEERS (Established 1875, Incorporated by Royal Charter, 1923) Patron-HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN President Major-General M E Tickell, CBE, MC, MA, C Eng, FICE ...................... 1979 Vice-Presiden ts Brigadier D L G Begbie, OBE, MC, BSc, C Eng, FICE ......................... 1980 Major General G B Sinclair, CBE, FIHE ................................. .... 1980 Elected Members Colonel B AE Maude, MBE, MA .................................. 1965 Major J M Wyatt, RE .............................................. 1978 Lieut-Colonel R M Hutton, MBE, BSc, C Eng, FICE, MIHE ............. 1978 Brigadier D J N Genet, MBIM ..................................... 1979 Colonel A H W Sandes, MA, C Eng, MICE .......................... 1979 Colonel G A Leech, TD, C Eng, FIMunE, FIHE ....................... 1979 Major J W Ward, BEM, RE ........................................ 1979 Captain W S Baird, RE ............................................ 1979 Lieut-Colonel C C Hastings, MBE, RE ............................... 1980 Lieut-Colonel (V) P E Williams, TD ................................ 1980 Brigadier D H Bowen, OBE ....................................... 1981 Ex-Officio Members Brigadier R A Blomfield, MA, MBIM .................................... D/E-in-C Colonel K J Marchant, BSc, C Eng, MICE ................................ AAG RE Brigadier A C D Lloyd, MA ..................................... -

Services & Music

S ERVICES & M USIC August 2014 ~ July 2015 Wednesday 30 July William Wilberforce, Social Reformer, 1833 8.30am Morning Prayer Berkeley Chapel 12.30pm Eucharist Berkeley Chapel 5.15pm Evening Prayer Quire Psalms 144, 145 Thursday 31 July Ignatius of Loyola, Founder of the Society of Jesus, 1556 8.30am Morning Prayer Berkeley Chapel 12.30pm Eucharist Elder Lady Chapel 5.15pm Evening Prayer Quire Psalm 146 Friday 1 August Feria 8.30am Morning Prayer Berkeley Chapel 12.30pm Eucharist Berkeley Chapel 5.15pm Evening Prayer Quire Psalm 6 Saturday 2 August Feria 8.30am Morning Prayer Berkeley Chapel 12.30pm Eucharist Berkeley Chapel 3.30pm CHORAL EVENSONG sung by St Edmund’s Choir of Whitton Quire Responses Neary Psalms 12, 13 Setting Stanford in C Hymn 244 Anthem The Peace of God – Rutter 2 bristol-cathedral.co.uk Sunday 3 August Seventh Sunday after Trinity 7.40am Morning Prayer Berkeley Chapel 8.00am Holy Communion (BCP) Quire 10.00am CATHEDRAL EUCHARIST Nave Preacher Canon Nicola Stanley Setting St John’s Mass – Terry Psalm 17.1-7 Motet Jubilate Deo – Ireland Hymns Processional 148 (omit *) Offertory 436 Communion 295 Post-communion 368 Voluntary Tuba Tune – Cocker 3.30pm CHORAL EVENSONG Quire Preacher The Revd Jules Barnes Responses Ferial Psalm 80.1-8 Setting Stanford in G Anthem Sicut Cervus – Palestrina Hymns 431; 239 Voluntary Allegro Assai, Senate No.4 – Guilt Sunday services are sung by St Edmund’s Choir of Whitton Monday 4 August Jean-Baptiste Vianney, Curé d’Ars, Spiritual Guide, 1859 8.30am Morning Prayer Berkeley Chapel 12.30pm -

4282 Supplement to the London Gazette, 2Nd April 1974

4282 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 2ND APRIL 1974 Actg. Sub Lts. (Special Duties List) confirmed Sub Lts. Col. J. F. WEBB, M.C., M.D., F.R.C.P. (202345) late on date and with seny. stated: R.A.M.C. retires on retired pay, 2nd Apr. 1974. J. A. BURCH, I. A. MCQUEEN, A. MILLAR, W. D. WELLSTEAD. 8th Jan. 1974 (8th Jan. 1973). REGULAR ARMY RESERVE OF OFFICERS Class II Col. D. W. WILLIAMS, O.B.E., T.D., A.D.C. (360189) ROYAL MARINES late INF., from T.A.V.R., Group A to be Col., 1st Apr. Capt. (Local Major) J. C. LUXMOORE, M.B.E., granted 1974. Honorary rank of Major on retirement 28th Feb. 1974. TERRITORIAL AND ARMY VOLUNTEER RESERVE Group A ROYAL NAVAL RESERVE Lt-Col. J. B. TIMMINS, O.B.E., T.D. (438617) from Surgn. Cdr. M. E. HINCKS, V.R.D., M.B., Ch.B., placed R.E. to be Col., llth Sep. 1973. on Retired List. 28th Feb. 1974. Lt.-Cdrs. placed on Retired List: HOUSEHOLD CAVALRY R. G. JONES, R.D., C. McC. WILLIAMS. 28th Feb. 1974. R.H.G./D. Lt-Cdr. (Sp) G. M. LEATHER, Dip. Arch., A.R.I.B.A., REGULAR ARMY placed on Retired List. 28th Feb. 1974. Lt. C. R. GOODALL (486652) resigns his commn., 1st Lt.-Cdr. (Sp) W. J. KENYON, R.D., B.Sc., placed on Apr. 1974. Retired List. 2nd Mar. 1974. Lt-Cdr. (Sp) C. H. SKENTELBURY, V.R.D., placed on ROYAL ARMOURED CORPS Retired List 10th Mar. -

Britain and the Development of Professional Security Forces in the Gulf Arab States, 1921-71: Local Forces and Informal Empire

Britain and the Development of Professional Security Forces in the Gulf Arab States, 1921-71: Local Forces and Informal Empire by Ash Rossiter Submitted to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Arab and Islamic Studies February 2014 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Abstract Imperial powers have employed a range of strategies to establish and then maintain control over foreign territories and communities. As deploying military forces from the home country is often costly – not to mention logistically stretching when long distances are involved – many imperial powers have used indigenous forces to extend control or protect influence in overseas territories. This study charts the extent to which Britain employed this method in its informal empire among the small states of Eastern Arabia: Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the seven Trucial States (modern day UAE), and Oman before 1971. Resolved in the defence of its imperial lines of communication to India and the protection of mercantile shipping, Britain first organised and enforced a set of maritime truces with the local Arab coastal shaikhs of Eastern Arabia in order to maintain peace on the sea. Throughout the first part of the nineteenth century, the primary concern in the Gulf for the British, operating through the Government of India, was therefore the cessation of piracy and maritime warfare.