Introduction Global Bollywood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EDITED TRANSCRIPT Eros STX Global Corporation – Business Update Call

NOVEMBER 04, 2020 / 9:30PM GMT, Eros STX Global Corporation – Business Update Call REFINITIV STREETEVENTS EDITED TRANSCRIPT Eros STX Global Corporation – Business Update Call EVENT DATE/TIME: NOVEMBER 04, 2020 / 9:30PM GMT REFINITIV STREETEVENTS | www.refinitiv.com | Contact Us ©2020 Refinitiv. All rights reserved. Republication or redistribution of Refinitiv content, including by framing or similar means, is prohibited without the prior written consent of Refinitiv. 'Refinitiv' and the Refinitiv logo are registered trademarks of Refinitiv and its affiliated companies. 1 NOVEMBER 04, 2020 / 9:30PM GMT, Eros STX Global Corporation – Business Update Call CORPORATE PARTICIPANTS Adam Fogelson: STX Films - Chairman Andy Warren: Eros STX Global Corporation - CFO Bob Simonds: Eros STX Global Corporation - Co-Chairman & CEO Drew Borst: Eros STX Global Corporation - EVP Investor Relations & Business Development Noah Fogelson: Eros STX Global Corporation - Co-President Rishika Lulla Singh: Eros STX Global Corporation - Co-President & Director CONFERENCE CALL PARTICIPANTS Eric Katz, Wolfe Research, LLC - Research Analyst Robert Routh, FBN Securities, Inc., Research Division - Research Analyst Robert Fishman, MoffettNathanson LLC - Analyst Ted Cronin, Citigroup Inc., Research Division - Research Analyst Tim Nollen, Macquarie Research - Senior Media Analyst PRESENTATION Operator Good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to Eros STX Global Corporation Business Update Call. This call is being broadcast live on the Internet, and a replay of the call will be available on the company's website. The company published earlier certain financial information, including a 20-F transition report and 6-K filing which are available on the company's website. The company would like to remind everyone listening that during this call, it will be making forward- looking statements under the safe harbor provisions of the federal securities laws. -

Part 05.Indd

PART MISCELLANEOUS 5 TOPICS Awards and Honours Y NATIONAL AWARDS NATIONAL COMMUNAL Mohd. Hanif Khan Shastri and the HARMONY AWARDS 2009 Center for Human Rights and Social (announced in January 2010) Welfare, Rajasthan MOORTI DEVI AWARD Union law Minister Verrappa Moily KOYA NATIONAL JOURNALISM A G Noorani and NDTV Group AWARD 2009 Editor Barkha Dutt. LAL BAHADUR SHASTRI Sunil Mittal AWARD 2009 KALINGA PRIZE (UNESCO’S) Renowned scientist Yash Pal jointly with Prof Trinh Xuan Thuan of Vietnam RAJIV GANDHI NATIONAL GAIL (India) for the large scale QUALITY AWARD manufacturing industries category OLOF PLAME PRIZE 2009 Carsten Jensen NAYUDAMMA AWARD 2009 V. K. Saraswat MALCOLM ADISESHIAH Dr C.P. Chandrasekhar of Centre AWARD 2009 for Economic Studies and Planning, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. INDU SHARMA KATHA SAMMAN Mr Mohan Rana and Mr Bhagwan AWARD 2009 Dass Morwal PHALKE RATAN AWARD 2009 Actor Manoj Kumar SHANTI SWARUP BHATNAGAR Charusita Chakravarti – IIT Delhi, AWARDS 2008-2009 Santosh G. Honavar – L.V. Prasad Eye Institute; S.K. Satheesh –Indian Institute of Science; Amitabh Joshi and Bhaskar Shah – Biological Science; Giridhar Madras and Jayant Ramaswamy Harsita – Eengineering Science; R. Gopakumar and A. Dhar- Physical Science; Narayanswamy Jayraman – Chemical Science, and Verapally Suresh – Mathematical Science. NATIONAL MINORITY RIGHTS MM Tirmizi, advocate – Gujarat AWARD 2009 High Court 55th Filmfare Awards Best Actor (Male) Amitabh Bachchan–Paa; (Female) Vidya Balan–Paa Best Film 3 Idiots; Best Director Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots; Best Story Abhijat Joshi, Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Male) Boman Irani–3 Idiots; (Female) Kalki Koechlin–Dev D Best Screenplay Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Abhijat Joshi–3 Idiots; Best Choreography Bosco-Caesar–Chor Bazaari Love Aaj Kal Best Dialogue Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra–3 idiots Best Cinematography Rajeev Rai–Dev D Life- time Achievement Award Shashi Kapoor–Khayyam R D Burman Music Award Amit Tivedi. -

Clare M. Wilkinson-Weber

Clare M. Wilkinson-Weber TAILORING EXPECTATIONS How film costumes become the audience’s clothes ‘Bollywood’ film costume has inspired clothing trends for many years. Female consumers have managed their relation to film costume through negotiations with their tailor as to how film outfits can be modified. These efforts have coincided with, and reinforced, a semiotic of female film costume where eroticized Indian clothing, and most forms of western clothing set the vamp apart from the heroine. Since the late 1980s, consumer capitalism in India has flourished, as have films that combine the display of material excess with conservative moral values. New film costume designers, well connected to the fashion industry, dress heroines in lavish Indian outfits and western clothes; what had previously symbolized the excessive and immoral expression of modernity has become an acceptable marker of global cosmopolitanism. Material scarcity made earlier excessive costume display difficult to achieve. The altered meaning of women’s costume in film corresponds with the availability of ready-to-wear clothing, and the desire and ability of costume designers to intervene in fashion retailing. Most recently, as the volume and diversity of commoditised clothing increases, designers find that sartorial choices ‘‘on the street’’ can inspire them, as they in turn continue to shape consumer choice. Introduction Film’s ability to stimulate consumption (responding to, and further stimulating certain kinds of commodity production) has been amply explored in the case of Hollywood (Eckert, 1990; Stacey, 1994). That the pleasures associated with film going have influenced consumption in India is also true; the impact of film on various fashion trends is recognized by scholars (Dwyer and Patel, 2002, pp. -

“Low” Caste Women in India

Open Cultural Studies 2018; 2: 735-745 Research Article Jyoti Atwal* Embodiment of Untouchability: Cinematic Representations of the “Low” Caste Women in India https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0066 Received May 3, 2018; accepted December 7, 2018 Abstract: Ironically, feudal relations and embedded caste based gender exploitation remained intact in a free and democratic India in the post-1947 period. I argue that subaltern is not a static category in India. This article takes up three different kinds of genre/representations of “low” caste women in Indian cinema to underline the significance of evolving new methodologies to understand Black (“low” caste) feminism in India. In terms of national significance, Acchyut Kanya represents the ambitious liberal reformist State that saw its culmination in the constitution of India where inclusion and equality were promised to all. The movie Ankur represents the failure of the state to live up to the postcolonial promise of equality and development for all. The third movie, Bandit Queen represents feminine anger of the violated body of a “low” caste woman in rural India. From a dacoit, Phoolan transforms into a constitutionalist to speak about social justice. This indicates faith in Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s India and in the struggle for legal rights rather than armed insurrection. The main challenge of writing “low” caste women’s histories is that in the Indian feminist circles, the discourse slides into salvaging the pain rather than exploring and studying anger. Keywords: Indian cinema, “low” caste feminism, Bandit Queen, Black feminism By the late nineteenth century due to certain legal and socio-religious reforms,1 space of the Indian family had been opened to public scrutiny. -

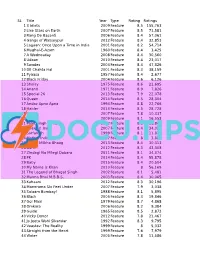

Aspirational Movie List

SL Title Year Type Rating Ratings 1 3 Idiots 2009 Feature 8.5 155,763 2 Like Stars on Earth 2007 Feature 8.5 71,581 3 Rang De Basanti 2006 Feature 8.4 57,061 4 Gangs of Wasseypur 2012 Feature 8.4 32,853 5 Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India 2001 Feature 8.2 54,714 6 Mughal-E-Azam 1960 Feature 8.4 3,425 7 A Wednesday 2008 Feature 8.4 30,560 8 Udaan 2010 Feature 8.4 23,017 9 Swades 2004 Feature 8.4 47,326 10 Dil Chahta Hai 2001 Feature 8.3 38,159 11 Pyaasa 1957 Feature 8.4 2,677 12 Black Friday 2004 Feature 8.6 6,126 13 Sholay 1975 Feature 8.6 21,695 14 Anand 1971 Feature 8.9 7,826 15 Special 26 2013 Feature 7.9 22,078 16 Queen 2014 Feature 8.5 28,304 17 Andaz Apna Apna 1994 Feature 8.8 22,766 18 Haider 2014 Feature 8.5 28,728 19 Guru 2007 Feature 7.8 10,337 20 Dev D 2009 Feature 8.1 16,553 21 Paan Singh Tomar 2012 Feature 8.3 16,849 22 Chakde! India 2007 Feature 8.4 34,024 23 Sarfarosh 1999 Feature 8.1 11,870 24 Mother India 1957 Feature 8 3,882 25 Bhaag Milkha Bhaag 2013 Feature 8.4 30,313 26 Barfi! 2012 Feature 8.3 43,308 27 Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara 2011 Feature 8.1 34,374 28 PK 2014 Feature 8.4 55,878 29 Baby 2015 Feature 8.4 20,504 30 My Name Is Khan 2010 Feature 8 56,169 31 The Legend of Bhagat Singh 2002 Feature 8.1 5,481 32 Munna Bhai M.B.B.S. -

Form 20-F Eros International

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, DC 20549 FORM 20-F ☐ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR 12(g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ☑ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended March 31, 2019 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ☐ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number 001-36176 EROS INTERNATIONAL PLC (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) Not Applicable (Translation of Registrant’s name into English) Isle of Man (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) 550 County Avenue Secaucus, New Jersey 07094 Tel: +1(201) 558 9001 (Address of principal executive offices) Oliver Webster IQ EQ (Isle of Man) Limited First Names House Victoria Road Douglas, IM2 4DF Isle of Man Tel: (44) 1624 630 630 Email: [email protected] (Name, Telephone, E-mail and/or Facsimile number and Address of Company Contact Person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act. Trading Title of each class Symbol(s) Name of each exchange on which registered A ordinary share, par value GBP 0.30 per share EROS The New York Stock Exchange Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act. None (Title of Class) Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Act None (Title of Class) Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the issuer’s classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the annual report. -

LIST of ORDINARY MEMBERS S.No

LIST OF ORDINARY MEMBERS S.No. MemNo MName Address City_Location State PIN PhoneMob F - 42 , PREET VIHAR 1 A000010 VISHWA NATH AGGARWAL VIKAS MARG DELHI 110092 98100117950 2 A000032 AKASH LAL 1196, Sector-A, Pocket-B, VASANT KUNJ NEW DELHI 110070 9350872150 3 A000063 SATYA PARKASH ARORA 43, SIDDHARTA ENCLAVE MAHARANI BAGH NEW DELHI 110014 9810805137 4 A000066 AKHTIARI LAL S-435 FIRST FLOOR G K-II NEW DELHI 110048 9811046862 5 A000082 P.N. ARORA W-71 GREATER KAILASH-II NEW DELHI 110048 9810045651 6 A000088 RAMESH C. ANAND ANAND BHAWAN 5/20 WEST PATEL NAGAR NEW DELHI 110008 9811031076 7 A000098 PRAMOD ARORA A-12/2, 2ND FLOOR, RANA PRATAP BAGH DELHI 110007 9810015876 8 A000101 AMRIK SINGH A-99, BEHIND LAXMI BAI COLLEGE ASHOK VIHAR-III NEW DELHI 110052 9811066073 9 A000102 DHAN RAJ ARORA M/S D.R. ARORA & C0, 19-A ANSARI ROAD NEW DELHI 110002 9313592494 10 A000108 TARLOK SINGH ANAND C-21, SOUTH EXTENSION, PART II NEW DELHI 110049 9811093380 11 A000112 NARINDERJIT SINGH ANAND WZ-111 A, IInd FLOOR,GALI NO. 5 SHIV NAGAR NEW DELHI 110058 9899829719 12 A000118 VIJAY KUMAR AGGARWAL 2, CHURCH ROAD DELHI CANTONMENT NEW DELHI 110010 9818331115 13 A000122 ARUN KUMAR C-49, SECTOR-41 GAUTAM BUDH NAGAR NOIDA 201301 9873097311 14 A000123 RAMESH CHAND AGGARWAL B-306, NEW FRIENDS COLONY NEW DELHI 110025 989178293 15 A000126 ARVIND KISHORE 86 GOLF LINKS NEW DELHI 110003 9810418755 16 A000127 BHARAT KUMR AHLUWALIA B-136 SWASTHYA VIHAR, VIKAS MARG DELHI 110092 9818830138 17 A000132 MONA AGGARWAL 2 - CHURCH ROAD, DELHI CANTONMENT NEW DELHI 110010 9818331115 18 A000133 SUSHIL KUMAR AJMANI F-76 KIRTI NAGAR NEW DELHI 110015 9810128527 19 A000140 PRADIP KUMAR AGGARWAL DISCO COMPOUND, G.T. -

KPMG FICCI 2013, 2014 and 2015 – TV 16

#shootingforthestars FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 kpmg.com/in ficci-frames.com We would like to thank all those who have contributed and shared their valuable domain insights in helping us put this report together. Images Courtesy: 9X Media Pvt.Ltd. Phoebus Media Accel Animation Studios Prime Focus Ltd. Adlabs Imagica Redchillies VFX Anibrain Reliance Mediaworks Ltd. Baweja Movies Shemaroo Bhasinsoft Shobiz Experential Communications Pvt.Ltd. Disney India Showcraft Productions DQ Limited Star India Pvt. Ltd. Eros International Plc. Teamwork-Arts Fox Star Studios Technicolour India Graphiti Multimedia Pvt.Ltd. Turner International India Ltd. Greengold Animation Pvt.Ltd UTV Motion Pictures KidZania Viacom 18 Media Pvt.Ltd. Madmax Wonderla Holidays Maya Digital Studios Yash Raj Films Multiscreen Media Pvt.Ltd. Zee Entertainmnet Enterprises Ltd. National Film Development Corporation of India with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. entity. (“KPMG International”), a Swiss with KPMG International Cooperative © 2015 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms Partnership KPMG, an Indian Registered © 2015 #shootingforthestars FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. entity. (“KPMG International”), a Swiss with KPMG International Cooperative © 2015 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms Partnership KPMG, an Indian Registered © 2015 #shootingforthestars: FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 Foreword Making India the global entertainment superpower 2014 has been a turning point for the media and entertainment industry in India in many ways. -

Portrayal of Women in the Popular Indian Cinema Wizerunek Kobiet W

Portrayal of Women in the Popular Indian Cinema Wizerunek kobiet w popularnym kinie indyjskim Sharaf Rehman THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS – RIO GRANDE VALLEY, USA Keywords Indian cinema, women, stereotyping Słowa klucze kino indyjskie, kobiety, stereotypy Abstract Popular Indian cinema is primarily rooted in formulaic narrative structure relying heavily on stereotypes. However, in addition to having been the only true “mass medium” in India, the movies have provided more than escapist fantasy and entertainment fare. Indian popular cinema has actively engaged in social and political criticism, promoted certain political ideologies, and reinforced In- dian cultural and social values. This paper offers a brief introduction to the social role of the Indian cinema in its culture and proceeds to analyze the phenomenon of stereotyping of women in six particular roles. These roles being: the mother, the wife, the daughter, the daughter-in-law, the widow, and “the other woman”. From the 1940s when India was fighting for her independence, to the present decade where she is emerging as a major future economy, Indian cinema has Artykuły i rozprawy shifted in its representation and stereotyping of women. This paper traces these shifts through a textual analysis of seven of the most popular Indian movies of the past seven decades. Abstrakt Popularne kino indyjskie jest przede wszystkim wpisane w schematyczną strukturę narracyjną. Mimo, że jest to tak naprawdę jedyne „medium masowe” w Indiach, tamtejsze kino to coś więcej niż rozrywka i eskapistyczne fantazje. Kino indyjskie angażuje się w krytykę społeczną i polityczną, promuje pewne Portrayal of Women in the Popular Indian Cinema 157 ideologie a także umacnia indyjskie kulturowe i społeczne wartości. -

Responses to 100 Best Acts Post-2009-10-11 (For Reference)

Bobbytalkscinema.Com Responses/ Comments on “100 Best Performances of Hindi Cinema” in the year 2009-10-11. submitted on 13 October 2009 bollywooddeewana bollywooddeewana.blogspot.com/ I can't help but feel you left out some important people, how about Manoj Kumar in Upkar or Shaheed (i haven't seen that) but he always made strong nationalistic movies rather than Sunny in Deol in Damini Meenakshi Sheshadri's performance in that film was great too, such a pity she didn't even earn a filmfare nomination for her performance, its said to be the reason on why she quit acting Also you left out Shammi Kappor (Junglee, Teesri MANZIL ETC), shammi oozed total energy and is one of my favourite actors from 60's bollywood Rati Agnihotri in Ek duuje ke Liye Mala Sinha in Aankhen Suchitra Sen in Aandhi Sanjeev Kumar in Aandhi Ashok Kumar in Mahal Mumtaz in Khilona Reena Roy in Nagin/aasha Sharmila in Aradhana Rajendra Kuamr in Kanoon Time wouldn't permit me to list all the other memorable ones, which is why i can never make a list like this bobbysing submitted on 13 October 2009 Hi, As I mentioned in my post, you are right that I may have missed out many important acts. And yes, I admit that out of the many names mentioned, some of them surely deserve a place among the best. So I have made some changes in the list as per your valuable suggestion. Manoj Kumar in Shaheed (Now Inlcuded in the Main 100) Meenakshi Sheshadri in Damini (Now Included in the Main 100) Shammi Kapoor in Teesri Manzil (Now Included in the Main 100) Sanjeev Kumar in Aandhi (Now Included in Worth Mentioning Performances) Sharmila Togore in Aradhana (Now Included in Worth Mentioning Performances) Sunny Deol in Damini (Shifted to More Worth Mentioning Performances) Mehmood in Pyar Kiye Ja (Shifted to More Worth Mentioning Performances) Nagarjun in Shiva (Shifted to More Worth Mentioning Performances) I hope you will approve the changes made as per your suggestions. -

375 © the Author(S) 2019 S. Sengupta Et Al. (Eds.), 'Bad' Women

INDEX1 A Anti-Sikh riots, 242, 243, 249 Aarti, 54 Apsaras, 13, 95–97, 100, 105 Achhut Kanya, 30, 31, 37 Aranyer Din Ratri, 143 Actress, 9, 18, 45n1, 54, 67, 88, 109, Armed Forces Special Powers Act, 170, 187, 213, 269, 342, 347–362, 255, 255n24 365–367, 369, 372, 373 Astitva, 69 Adalat, 115, 203 Atankvadi, 241–256 Akhir Kyon, 69 Azmi, Shabana, 54, 68 Akhtar, Farhan, 307, 317n13 Alvi, Abrar, 60 Ambedkar, B.R., 31, 279n2 B Ameeta, 135 Babri Masjid, 156, 160 Amrapali, 93–109, 125 Bachchan, Amitabh, 67, 203, 204, Amu, 243–249 210, 218 Anaarkali of Aarah, 365, 367, 370, 373 Bagbaan, 69 Anand, Dev, 7n25, 8n27, 64 Bahl, Mohnish, 300 Anarkali, 116, 368–369 Bandini, 18, 126, 187–199 Andarmahal, 49, 53 Bandit Queen, 223–237 Andaz, 277–293 Bar dancer, 151 Angry Young Man, 67, 203–205, 208, Barjatya, Sooraj, 297, 300, 373 218, 219 Basu Bhattacharya, 348, 355 Ankush, 69 Basu, Bipasha, 88 1 Note: Page numbers followed by ‘n’ refer to notes. © The Author(s) 2019 375 S. Sengupta et al. (eds.), ‘Bad’ Women of Bombay Films, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26788-9 376 INDEX Bedi, Bobby, 232–235 237, 261, 266–268, 278, 279, Benaras, 333, 334 283, 283n8, 285, 291, 318, 332, Benegal, Shyam, 7n23, 11, 11n35, 13, 334, 335, 338, 343, 350, 351, 13n47, 68, 172n9, 348, 351, 366 355, 356, 359, 361, 372n3 Beshya/baiji, 48, 49, 55, 56 Central Board of Film Certification Bhaduri, Jaya, 209, 218 (CBFC), 224, 246, 335, Bhagwad Gita, 301 335n1, 336 Bhakti, 95, 98, 99, 101, 191n11, 195, Chak De! India, 70 195n18, 196 Chameli, 179–181 Bhakti movement, 320 Chastity, 82, -

LALITHA GOPALAN Fall 2010 EMPLOYMENT

LALITHA GOPALAN Fall 2010 EMPLOYMENT Associate Professor, Department of Radio-Television –Film and Department of Asian Studies, University of Texas at Austin, Fall 2007-present. Visiting Associate Professor, Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures, University of California, Berkeley, Spring 2009. Associate Professor, School of Foreign Service and Department of English, Georgetown University, 2002-07. Assistant Professor, School of Foreign Service and Department of English, Georgetown University, 1992-2002. EDUCATION Ph.D. University of Rochester. 1993. Comparative Literature Program, Department of Foreign Languages, Literatures, and Linguistics. M.A. (Anthropology) University of Rochester, 1986 M.A. (Sociology) Delhi School of Economics, 1984 B.A. (Economics) Madras Christian College, 1982 PUBLICATIONS BOOKS 24 Frames: Indian Cinema. Edited. London: Wallflower Press, 2010. Bombay. BFI Modern Classics. London: British Film Institute. December 2005. Cinema of Interruptions: Action Genres in Contemporary Indian Cinema. London: British Film Institute. 2002. (Indian Reprint Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2002) 2 ARTICLES AND ESSAYS ‘Introduction.’ 24 Frames: Indian Cinema. London: Wallflower Press. Ed. Lalitha Gopalan. London: Wallflower Press, 2010. ‘Film Culture in Chennai.’ Film Quarterly, Volume 62.1 (Fall 2008). ‘Indian Cinema.’ In An Introduction to Film Studies. Ed. Jill Nelmes. 4th Edition. London: Routledge. 2006. (Revised and expanded version of the essay published in the 3rd Edition, 2003) ‘Avenging Women in Indian Cinema.’ Screen. 38.1 (Spring 1997): 42-59. Screen Award for the Best Article submitted in 1996. ‘Coitus Interruptus and the Love Story in Indian Cinema.’ Representing the Body: Gender Issues in India's Art. Ed. Vidya Dehejia. New Delhi: Kali for Women, 1997. 124-139. ‘Putting Asunder: Fassbinder and The Marriage of Maria Braun.’ Deep Focus January 1989: 50- 57.