Queensland Industrial Relations Commission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

They're Just Ads

Edited transcripts of interviews with Greville Patterson (20/11/98, 27/11/98, 16/3/99) used in preparation of thesis They’re just ads: Greville Patterson’s life in advertising by Sylvia Bannah Submitted as partial requirement for the Postgraduate Diploma in Arts (History) The University of Queensland 1999 Applied History Centre Department of History The University of Queensland St Lucia 4072 14 ^ g S iO , p ^ /T p r - ' TU * a * .âirfíiiÍ>..:áií 3^&° They’re just ads: Greville Patterson’s life in advertising 1 Interview transcripts Fri 20/11/98 - Side 1. [1973-76 Jones Knowles McCann Erickson] I was put on there as an art director, mostly doing layouts for various accounts like Rover Mowers, Trittons, J. B. Conlan menswear store, Queensland Permanent Building Society - they're gone, Wallace Bishop, Mathers. I guess they were all pretty well Brisbane based accounts. There was a mixture of press and television advertising. I got to make my first TV commercial there for Wallace Bishop You need Timing\ I did that to a 50's pop song, by Sam Cooke. It was the first TV commercial where I actually sat down to write storyboards, camera movements and all that sort of stuff. Ronny [Johanson] shot it and Max [Bannah] did the end animation. It would have been done around 1975. I've got an Art Director's Annual, the Art Director's Club had only just been formed then, and we got an award for it - Best TV Commercial - which was a bit of a surprise. I wrote my first jingle there, the Adsett Treatment. -

C. Merchant (Media Dir), L. Maker (Accnt Boys' Town, British Leyland

322 Advertising Agencies (Queensland) Executives:PaulJones(chrmn),Bruce I'state repr.: Foote, Cone & Belding Pty Knowles (secy), W. Bristow (creative dir), J. Ltd-Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide. Adcraft Kleimeyer (accnt), Dorothy Bruce (art dir), Service, 125 St George's Terrace, Perth. C. Merchant (media dir), L. Maker (accnt Accreditation: AMAA. exec.), B. Bellamy (prod. mngr). Has owntestkitchen and model store I'staterepr.: Jones Knowles Vinnicombe facilities. Shirley Pty Ltd, Sydney. Clients: Amagraze Ltd, Ashby Bros Pty Accreditation: AMAA. Ltd, Australian Paper Manufacturers Ltd, Clients: Annand & Thompson Pty Ltd, Cen- Bundaberg Distilling Co. Ltd, Butler Bros tral Queensland Broadcasting Network (4IP, Australia (Pty) Ltd, Butler Bros (Nundah), 4LG, 4LM), Freedman & Co., Jenyns Patent Barnes Engineering Pty Ltd, Brisbane Milk Corset Pty Ltd, Mathers Pty Ltd, O'DonnellBoard and Milk Sales Promotion Advisory Griffin, QId Sub -Normal Children's Welfare Committee, Butter Marketing Board, Camera - Association, Rover Mowers Pty Ltd, Shirleys craft Pty Ltd, Coles Constructions Pty Ltd, Shoes Pty Ltd, T. Tristram Pty Ltd, Trittons Coles New World Supermarkets, Colourtile Pty Ltd, Universal Telecasters (Qld) Limited Australia Pty Ltd, Dollar Curtains, Edward (TVQ), Wallace Bishop Pty Ltd, Woolworths Fletcher & Co. Pty Ltd, Farsley Motors Pty (Oust.) Ltd (St Mark). Ltd, Imperial Chemical Industries of Aus- tralia and New Zealand, Mackay & Co. Pty Ltd,MiddletonPtyLtd,Max'sSpeedo LE GRAND ADVERTISING PTY LTD Electric Service, R. J. O'Sullivan Pty Ltd, 35 Creek St, Brisbane, 4000. Phone 31-2891. OrientalTea Co./Robur TeaCo.,Pauls Chairman: J. Le Grand. Foods Ltd, Pauls (NT) Pty Ltd, Queensland NewspapersPty Ltd,QueenslandTyre Managing director: R. P. Magan. Retreading Co.Ltd, QUF Industries Ltd, Accreditation: AMAA. -

The Inside Story – October 2011 Nest Coffee Lounge – Carrara

The Inside Story – October 2011 Nest Coffee Lounge – Carrara JASON Morris has opened his first business on the Gold Coast. His design for this coffee lounge rendezvous has seen the creation of an inviting space serving delicious coffee from his own blend – there is even a fireplace in a private nook. Simpatico Jason knows coffee and service, and Projects Queensland were engaged for his fitout which was completed in record time. GRAEME Wakefield Managing Director, Race Property Leasing and Management said, “We are very proud of the final result achieved at Woolworths Carrara. The centre was fully leased on opening and the mix includes IMO Sushi, Subway, Nest Coffee Lounge, Hair Plus salon and beauty, Cafe Monaco and BWS bottle shop.” The total centre specialty GLA – 351m2 Jason Morris at work Nest Coffee lease term – 8 years Paragon Jewellery – HILTON retail precinct – Surfers Paradise TIBOR and Janet Palatinus, with 35 years “Centre Management has been very helpful experience in the retail jewellery business and we are delighted with the quality and have opened a new 70m2 store at the fitout of Paragon delivered by the Projects Hilton, with a range that will appeal to Queensland team,” he said. every taste and can work with clients for The 70m2 fitout of PARAGON was redesigns of existing jewellery. completed in 3.5 weeks. Tibor said he was very confident in the future of Surfers Paradise as a national and international tourist destination – Brad Dunne with Tibor and Janet Palatinus the Hilton Hotel and the Hilton retail ...the Hilton Hotel precinct by Brookfield Multiplex is helping revitalise Surfers Paradise and confirmed and the Hilton retail our decision to be a part of this iconic precinct by Brookfield development. -

For Personal Use Only Use Personal For

Brisbane Broncos Level 1, 92 Fulcher Rd, Red Hill, Qld 4059 T: 07 3858 9111 F: 07 3858 9112 www.broncos.com.au A.B.N. 41 009 570 030 Principal Sponsor 23 February 2012 To: ASX Company Announcements Platform BRISBANE BRONCOS LIMITED AND CONTROLLED ENTITIES 2011 FINANCIAL RESULTS Please find attached the following documents in relation to the 2011 financial results for Brisbane Broncos Limited and its controlled entities: Earnings Release Appendix 4E – Preliminary Final Report 2011 Financial Report Independent Audit Report and Auditor’s Independence Declaration Yours faithfully Brisbane Broncos Limited Louise Lanigan Company Secretary For personal use only Platinum Sp onsors EARNINGS RELEASE FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2011 Brisbane, 23 February 2012 FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE The Board announced today the audited results for the Brisbane Broncos Group for the financial year ended 31 December 2011. The Group recorded an after tax profit for the 31 December 2011 financial year of $1,360,000 compared to the 2010 result of $980,607. The before tax profits for the 2011 and 2010 financial years were $2,021,000 and $1,463,038 respectively. As a result of the strong financial position of the Group, the Board are pleased to be able to pay a fully franked dividend of one cent per share, an increase of 100% on the previous year. Revenue The Group recorded gross revenue for the 2011 financial year of $28,973,121 which is a $2,399,040 (9%) increase from 2010. The January 2011 floods in south east Queensland significantly impacted Brisbane Broncos Limited early season membership and corporate revenues. -

Dr Phil Jauncey

Dr Phil Jauncey Dr Phil Jauncey is a performance psychologist, whose activities include corporate facilitation, education of staff and managers, personal success mentoring, speaking about parenting, counselling and working in the areas of sport and performance. As a keynote speaker, Phil has been described as "one of Queensland's most dynamic presenters...has stimulated sports and professional audiences alike. His contagious passion for life has an overwhelming ability to leave guests wanting more as he tackles the more technical mind sets of self development and gets back to basics." (Brisbane Breakfast Club). Phil has a strong academic background and has 4 degrees; B.A., B.D., Masters and Doctorate in Counselling and Educational Psychology. He has lectured at Mt Gravatt CAE (now Griffith University), QUT and the University of Queensland in areas such as educational psychology, social psychology, developmental psychology, counselling, marketing and multicultural psychology. He was voted the "Outstanding Lecturer of the Year of 1990" at QUT. He is a registered psychologist, and a member of the Australian Psychological Society and the APS College of Sports Psychologists. In the corporate world, Phil’s expertise in language and social science resulted in his being appointed advertising and promotions manager at Dreamworld in 1988 and then marketing and educational specialist for Mincom from 1988 to 1990. He also developed methods of improving advertising for both television and radio. In 1991 Phil became an independent consultant, working in the areas of business, sport, education and counselling. He is often called upon as a keynote speaker locally, nationally and internationally. He also conducts in-house workshops for companies in staff evaluation, understanding self, sales, marketing strategy and change management. -

Nextthursday Credentials 2021

Agency Credentials_ © 2021 nextThursday Introduction_ Welcome to the world of nextThursday_ 'know how.' We know how to help your brand strike gold, and over the following pages you'll get to know how we do it, did it, and got the t-shirt for other brands we've worked with. It's a blueprint - how we like to work so that you get the best from us. If you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to ask. We want you to know what you're getting into and what you'll get out of working with us. It’s the reasonable side of our unreasonable ideas agency. Cheers, Dan Adler From concept to customer, our full suite of in-house services supports every step of a brand’s journey. u n r e a s o n a b l e i d e a s We live in The Age of Unreason, an era where change is constant, random, and discontinuous. Consumers are predictably irrational. They use instinct, intuition and emotion to make the vast majority of decisions. Believing that marketing succeeds because they’re reasonable, is misplaced. Success for our clients means hitting unreasonable targets (2% growth? Easy. 20% growth? Now that’s being unreasonable). So, in order to achieve the unreasonable results you need unreasonable ideas. b r a n d s w h o m a d e u s TAKE THE LEAD Brand position campaign for TJM THE NEED In 1973, Lloyd Taylor, Cliff Jones, and Steve Mollenhauer were mates who raced souped-up vee-dub beach buggies. -

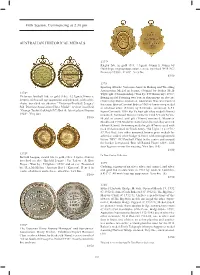

Fifth Session, Commencing at 2.30 Pm AUSTRALIAN HISTORICAL

Fifth Session, Commencing at 2.30 pm AUSTRALIAN HISTORICAL MEDALS 1377* Rugby fob, in gold (9ct, 4.3gms) 40mm x 30mm by Dunklings, ring top suspension, reverse inscribed "H.R.F.C/ Premiers 1930/L. Pevitt". Very fi ne. $150 1378 Sporting Awards: Victorian Amateur Boxing and Wrestling Association Medal in bronze (50mm) by Stokes Melb 1374* 'Flyweight / Championship / Won by / P.O'Shannessy / 1931'; Victorian football fob, in gold (15ct, 12.9gms)(36mm x Boxing medal featuring two boxers shaping-up on obverse 28mm), with scroll top suspension and pin back, with safety (48mm) by Stokes, unnamed; Australian Maccabi Council chain, inscribed on obverse "Victorian/Football League/ Interstate Sports Carnival Sydney 1963-64 swimming medal Sub Districts/Association/Clota Medal" reverse inscribed in oxidised silver (51mm) by K.G.Luke, unnamed; A.P.I. "George Taylor/Oakleigh F.C./Best & fairest player/Season Fijian Carnivale 1990 Fiji Vs Aust gilt alloy medal (48mm) 1928". Very fi ne. unnamed; Earlwood Wanderers Soccer Club 5 Years Service $300 Medal in enamel and gilt (38mm) unnamed; Mountex Blackheath 1994 Medal in enamel and silvered alloy on neck ribbon (42mm); Swimming medal in gilt (47mm) cased with neck ribbon named to 'Dads Army / Sid Light / 1.2.1978 / 87 Not Out'; two other unnamed bronze prize medals for athletics; voided silver badge (41mm) with monogrammed letters 'NFC' (N? Football Club) in the centre and around the border is engraved 'Best All Round Player 1889', with four lugs on reverse for wearing. Very fi ne. (10) $100 1375* Ex Tom Hanley Collection. Barfold League, award fob in gold (15ct, 5.4gms, 26mm) inscribed on obv. -

To Download Resume April 2019

Dr Phil Jauncey Dr Phil Jauncey is a performance psychologist, whose activities include corporate facilitation, education of staff and managers, personal success mentoring, speaking about parenting, counselling and working in the areas of sport and performance. As a keynote speaker, Phil has been described as "one of Queensland's most dynamic presenters...has stimulated sports and professional audiences alike. His contagious passion for life has an overwhelming ability to leave guests wanting more as he tackles the more technical mind sets of self development and gets back to basics." (Brisbane Breakfast Club). Phil has a strong academic background and has 4 degrees; B.A., B.D., Masters and Doctorate in Counselling and Educational Psychology. He has lectured at Mt Gravatt CAE (now Griffith University), QUT and the University of Queensland in areas such as educational psychology, social psychology, developmental psychology, counselling, marketing and multicultural psychology. He was voted the "Outstanding Lecturer of the Year of 1990" at QUT. He is a registered psychologist, and a member of the Australian Psychological Society and the APS College of Sports and Exercise Psychologists. In the corporate world, Phil’s expertise in language and social science resulted in his being appointed advertising and promotions manager at Dreamworld in 1988 and then marketing and educational specialist for Mincom from 1988 to 1990. He also developed methods of improving advertising for both television and radio. In 1991 Phil became an independent consultant, working in the areas of business, sport, education and counselling. He is often called upon as a keynote speaker locally, nationally and internationally. He also conducts in-house workshops for companies in staff evaluation, understanding self, sales, marketing strategy and change management. -

2017 / 2018 Rotary Year

Rotary Club of Brisbane Website: http://brisbanerotary.org.au Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/brisbanerotary LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/organization/17885186 2017 / 2018 ROTARY YEAR Daniel Vankov, President 2017 / 2018 Email: [email protected] 1 CONTENTS President's report .................................................................................................. 2 The team ............................................................................................................... 7 Messages from the Committees ............................................................................ 8 Club goals ............................................................................................................ 12 Speakers and members in the spot light .............................................................. 14 President's Bottle of Wine Awards ....................................................................... 16 Calendar of activities ........................................................................................... 18 Projects and fundraising ...................................................................................... 21 Developed project proposals ............................................................................... 23 Club reality check ................................................................................................ 27 Media snapshots ................................................................................................. 29 Cover photo. President Daniel -

The Life and Work of Dr. Eleanor Greenham

26 A Pioneer not a Traditionalist: the Life and Work of Dr. Eleanor Greenham by Lesley M. Williams Address 1 February; 1992, Centenary of Ipswich Girls' Grammar School On 1 February 1892, the headmistress of Ipswich Girls' Grammar School, Miss Fanny Hunt, herself the first woman science graduate from Sydney University, enrolled the first pupils. It is fitting that the girl she enrolled as No.l made a place for herself in the history of Queensland when she became the first native-born medical woman to practise in the state. Eleanor Constance Greenham (Ella to her family and friends) was born on 15 April 1874, the second eldest of five children and the only daughter of John and Eleanor (nee Johnstone) Greenham of Limestone Street, Ipswich, later of 57 Salisbury Road. John Greenham had immigrated with his parents from Somerset in 1855 when only 14 years of age and worked for some years with Cribb & Foote's, later starting out in business as Greenham & Co with Thomas Bennett.' Ultimately he became Chairman of Directors of Greenhams Pty. Ltd. which owned a large block in the business centre between Nicholas and Brisbane Streets. In the 1880s, he served as Alderman on the Ipswich City Council. He was also a foundation shareholder and first Chairman of Directors of Phoenix Engineering Company. Eleanor attended the Ipswich Central Girls' and Infants' School for her primary education; and in 1889 and 1890, she attended the Brisbane Girls' Grammar School where she won the English prize and the Natural History prize for Fourth Form.^ With the prospect of a Girls' Grammar School opening in her own city, Eleanor apparently decided to postpone her senior studies and complete her schooling there. -

A History of the Early Days of Rock 'N' Roll in Brisbane . . . As Told by Some

A history of the early days of rock ‘n’ roll in Brisbane . as told by some of the people who were there. Geoffrey Walden B. Ed., M. Ed. (Research) Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy to the School of Cultural and Language Studies in Education, Faculty of Education Queensland University of Technology January 2003. Abstract The music history that is generally presented to students in Queensland secondary schools as the history of music is underpinned by traditions associated with the social and cultural elite of colonialist Europe. On the other hand, contemporary popular music is the style with which most in this community identify and its mass consumption by teenagers in Brisbane was heralded with the arrival of rock ‘n’ roll in the mid-1950s. This project proposes that the involvement of the music education system in, and the application of digital technology to, the collection and storage of musical memories and memorabilia with historical potential is an important first step on the journey to a music history that is built on the democratic principles of twenty-first century, culturally and socially diverse Australia rather than on the autocratic principles of colonialist Europe. In taking a first step, this project focused on collecting memories and memorabilia from people who were involved in an aspect of the coming of rock ‘n’ roll to Brisbane. Memories were collected in the form of recorded conversations and these recordings, along with other audio and visual material were transferred to digital format for distribution. As an oral history focusing its attention on those who were involved with the coming of rock ‘n’ roll to Brisbane in the mid to late 1950s and the early 1960s, this project is intended as a starting point for that journey. -

Victorian Numismatic Newsletter

Victorian Numismatic Newsletter Issue Four September 2020 Welcome Welcome to the fourth newsletter for this year, which we hope you‟re finding an informative and a welcoming distraction. With our physical and mental health being of paramount importance it‟s even more essential to keep ourselves healthy and safe. With regular exercises, nutritious food, minimising „couch-potato‟ habits, and regular contact with relatives and friends we can improve our health and maintain as much as possible a positive attitude. This is especially important under the current circumstances here in Victoria. With move- ment restrictions, indoor activities such as home based projects such as gardening, are the way to go. But after a long day or a week full of ad-hoc duties, unwinding by engaging in our hobbies is very natural. And why not? The Association continues its monthly audio-visual meetings and until the suspension of physical meetings is lifted, these will continue. For members with no computer access we will continue to distribute our publica- tions to keep you up to date. We encourage you to continue to submit content for the ongoing Newsletters as well as for our forthcoming Journals. We‟re planning on a bumper annual edition for December and a commemorative issue in April/May 2021 to celebrate our 75th anniversary. Such content may relate to study in your specialty, or some background on your recent or older acquisition, or recollections of your past NAV memories for the Anniversary issue. Again, we encourage you to stay positive, be proactive and to remain in touch wherever possible We’re all in this together! NAV members, friends with your friends.