Nationalization and Mining: Lessons from Zambia Budget Deficit Increased to US$150 Million

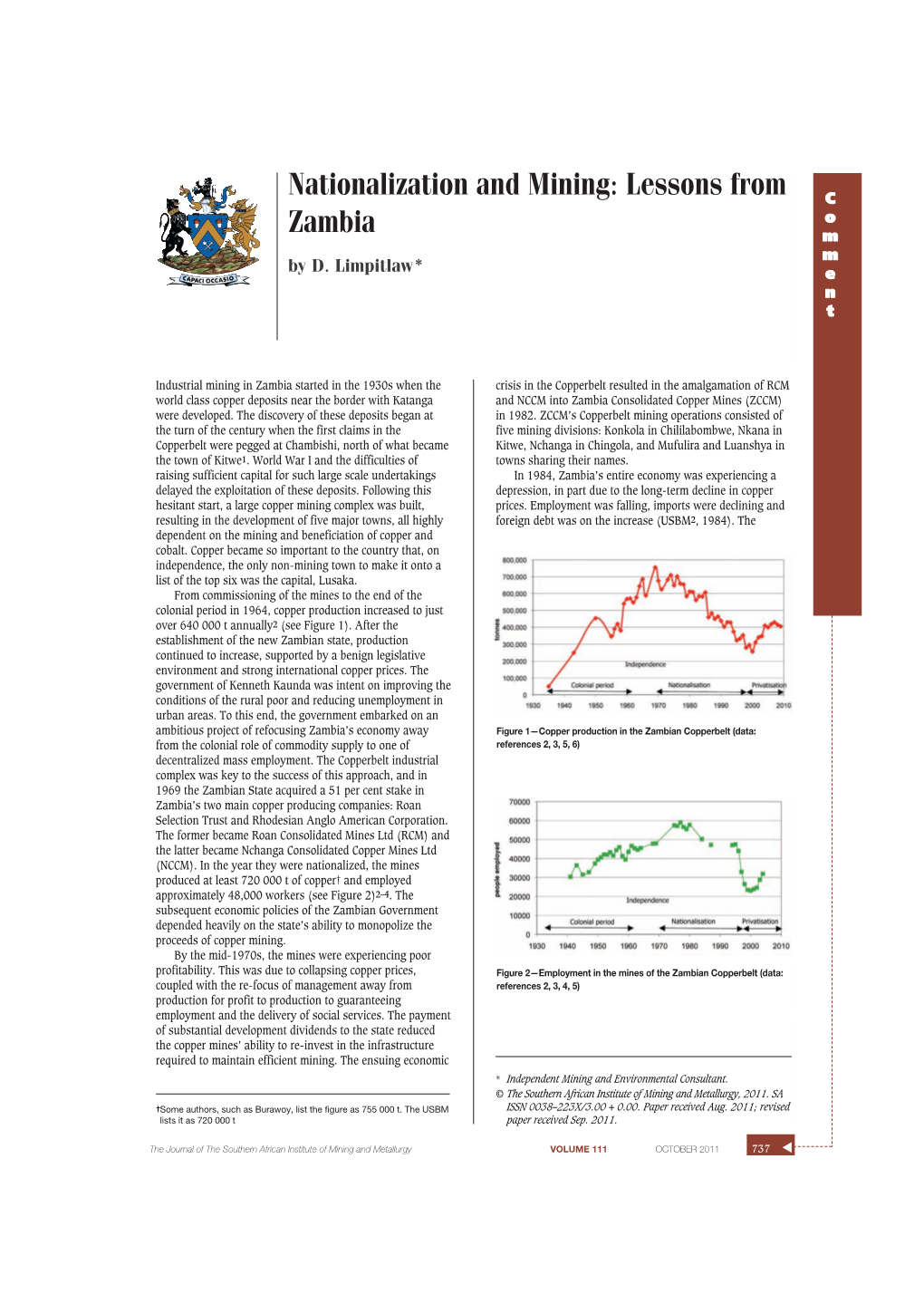

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kabwe, Zambia

Mortimer Hays-Brandeis Traveling Fellowship Final Report, Hrvoje Slovene House Secrets: Industrial Tales in one of the World's Most Contaminated Cities: Kabwe, Zambia For the past five years, my primary focus in photography has been to document abandoned, nineteenth-century factories and industrial spaces, as well as to show the irreparable damage modem industrialism has had on the global environment and its population. By photographing the devastating effects on local neighborhoods wrought by factories and industry, my intention has been to show how seemingly isolated problems have contributed to the global environmental crisis we are witnessing today. To date this project has taken me to Manchester, England-the birthplace of the industrial revolution; to Cleveland, Ohio; and Zagreb, Croatia. With the generous help of the Mortimer Hays- Brandeis Traveling Fellowship, I expanded this project to include Kabwe, Zambia. The mining of lead there by a Chinese-based company continues to put the population of hundreds of thousands at serious risk. Through my photographs, I showed the impact of modem industrialism on the real, day-to-day experiences of people and their industrialized habitats. Although my original intention was to visit and document the effects oflead pollution in Kabwe, Zambia; Linfen, China; and Dzerzhinsk, Russia, I found a plethora of material in Zambia, and spent the majority of my time there. I first visited Kabwe in June 2007 and stayed there for three months. During that time I got in touch with local NGOs and familiarized myself with their work on the field. During that time I also became aware of the scale of the lead pollution problem on the location. -

Zambia Mining and Public Health Mtg Rep April2018.Pdf

MINING AND PUBLIC HEALTH IN ZAMBIA MEETING REPORT C Mwansa 2018 Ministry of Health, Zambia in collaboration with the Regional Network for Equity in Health in East and Southern Africa (EQUINET) SBH Centre, Lusaka, Zambia April 10 2018 Contents 1. Background and objectives ....................................................................... 2 2. Opening session ....................................................................................... 3 3. Presentations from Zambia ....................................................................... 4 3.1 Mining and public health in Zambia ............................................................ 4 3.2 Survey findings on mining, TB and health in Zambia.................................. 5 3.3 Lead poisoning in Kabwe ........................................................................... 6 4. Mining and health: A regional perspective ................................................ 7 5. Discussions............................................................................................... 9 5.1 Discussion on public health and mining in Zambia ..................................... 9 5.2 Discussion on regional standards and co-operation ................................. 10 6. Recommendations .................................................................................. 11 7. Closing .................................................................................................... 12 Appendix 1: Programme ............................................................................... -

A History of Mining in Broken Hill (Kabwe): 1902-1929 Buzandi Mufinda

A HISTORY OF MINING IN BROKEN HILL (KABWE): 1902-1929 BY BUZANDI MUFINDA THIS THESIS HAS BEEN SUBMITTED IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE FACULTY OF THE HUMANITIES, FOR THE CENTRE FOR AFRICA STUDIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF THE FREE STATE. FEBRUARY 2015 SUPERVISOR: PROF. I.R. PHIMISTER CO-SUPERVISOR: DR L. KOORTS DECLARATION I declare that the dissertation hereby submitted by me for the Master of Arts degree at the University of the Free State is my own independent work and has not previously been submitted by me at another university/faculty. I furthermore cede copyright of the dissertation in favour of the University of the Free State. Buzandi Mufinda i DEDICATION I dedicate this work to the memory of my late parents, Edward Mufinda, and Rosemary Mufinda, and to my niece Chipego Munene and hope one day she might follow in the footsteps of academia. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Glory is to the enabling power of the Almighty God whose hand has worked through many ways to make it possible for me to accomplish this study. I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my supervisor, Professor Ian Phimister, for the patient guidance, encouragement and advice he has provided throughout my time as his student. I have been extremely lucky to have a supervisor who cared so much about my work, and who responded to my questions and queries so promptly. To Doctor Lindie Koorts, your expertise in structuring and editing of this work continually amazed me. Thank you also for your moral support. -

Copper for Development Report 2021

2021 COPPER FOR DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2 COPPER FOR DEVELOPMENT REPORT Contents List of tables ii List of figures ii Acknowledgements iii List of Abbreviations iv Executive Summary v 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Study Objectives 1 1.2 Overview of Methodology 1 2 Zambia’s Macroeconomic Context 2 2.1 Mining Economic Contribution 2 2.1.1 Contribution to GDP 3 2.1.2 Contribution to International Trade 3 2.1.3 Contribution to Domestic Revenues 5 2.1.4 Contribution to Employment 5 3 Legal and Institutional Framework 5 3.1 The Significance of a Legal and Institutional Framework in the Extractive Sector 5 4 Expenditure in the Priority Sectors (Health, Education and Agriculture) 8 5 Copper Revenue Management at Subnational Level in Zambia 10 5.1 The Transfer of Mining Revenues at Local Government Level 10 5.1.1 Findings from Key Informant interviews with Local Authorities 13 5.2 The role of Chiefs in Mineral Revenue Management 15 5.2.1 Key Informant Interviews with Chiefs 15 5.3 Analysis of Subnational Transfers 17 5.4 Rationale for mineral revenue sharing mechanism 18 6 Case Studies of Mineral Revenue Sharing Mechanisms in Selected African countries 20 6.1 Mineral Revenue Sharing Mechanism in Ghana 20 6.1.1 Challenges of Mineral Revenue Sharing in Ghana 20 6.2 Mineral Revenue Sharing Mechanism in Botswana 6.2.1 The Role of Mineral Revenue in Botswana 21 6.2.2 Lessons from Botswana’s Mineral Revenue Management “Mechanism” 22 7 Conclusion and Recommendations 22 7.1 Main Findings 22 7.1.1 Mining Sector Specific Findings 22 7.1.2. -

WIDER Working Paper 2018/51

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Lundstøl, Olav; Isaksen, Jan Working Paper Zambia's mining windfall tax WIDER Working Paper, No. 2018/51 Provided in Cooperation with: United Nations University (UNU), World Institute for Development Economics Research (WIDER) Suggested Citation: Lundstøl, Olav; Isaksen, Jan (2018) : Zambia's mining windfall tax, WIDER Working Paper, No. 2018/51, ISBN 978-92-9256-493-3, The United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER), Helsinki, http://dx.doi.org/10.35188/UNU-WIDER/2018/493-3 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/190100 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu WIDER Working Paper 2018/51 Zambia’s mining windfall tax Olav Lundstøl1 and Jan Isaksen2 May 2018 Abstract: In 2008, the Government of Zambia reformed its mining tax regime for large-scale copper mines through a unilateral legislative change. -

Mining, Resources & Underdevelopment

Review of African Political Economy No. 117:361-366 © ROAPE Publications Ltd., 2008 Scrambling to the Bottom? Mining, Resources & Underdevelopment Ray Bush The 21st century race for resources and territory has simultaneously induced cries of optimism from donors and the international agencies, but there is despair from critics and many on the continent: that plunder and looting continues in a manner reminiscent of the colonial past (Bond, 2006; Bush, 2007). But is the current scramble similar to the previous looting of African resources? Are there no benefits from the demand for Africa’s resources? Can the current dynamic be characterised as a scramble or, is it simply ‘business as usual’ for the good of civil society? Africa holds 42% of the world’s share of bauxite; 38% of its uranium; 42% of the world’s reserves of gold; 73% of its platinum; 88% of diamonds. The continent also has enormous reserves of non-ferrous metals like chromite (44%), manganese (82%), vanadium (95%) and cobalt (55%). Despite this abundance of resource wealth – and these figures probably underestimate resource availability because of limited surveying – there is little evidence that raw materials are translated into growth with justice and equality. And there is only limited evidence that strategies to convert local resources nationally, or to pool them regionally, will generate real value added for Africans. For while the continent’s average economic growth rates have been high since 2000 compared with previous decades due almost entirely to the unprecedented price of crude oil and metals, African raw material producers do not benefit from the resource scramble. -

Economic Development of Southern Africa...5

RESEARCH TOPIC 5 MINING, MINERALS AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND THE TRANSITION TO SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT IN SOUTHERN AFRICA SEPTEMBER 2001 RESEARCH TEAM: FT CAWOOD, S KANGWA, AS MACFARLANE, AND RCA MINNITT RESEARCH TEAM COORDINATOR: RCA MINNITT School of Mining Engineering, University of the Witwatersrand Private Bag 3,WITS. 2050. South Africa. Tel. +27-11-717-7403 UNIVERSITY OF THE WITWATERSRAND Contents 1. THE CONTRIBUTION OF THE MINING AND MINERALS SECTOR TO THE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF SOUTHERN AFRICA...........................................5 Summary...................................................................................................................6 1.0 Growth in the global economy. .........................................................................7 2.0. Mining in the SADC Region...........................................................................13 2.2 Employment in the SADC Mining Industry ...................................................30 3.0 PERFORMANCE OF MAJOR MINERALS.................................................34 4.0 DEVELOPMENTS IN SADC MEMBER STATES ......................................53 4.2. Policy and Administration Changes...............................................................65 4.2.2 Administration of the Sector.........................................................................72 5.0. Geological exploration and mapping. ..............................................................74 6.0 Globalisation. ...................................................................................................89 -

And OPPORTUNITIES for COOPERATION in SOUTHERN AFRICA

) -Annex B MINING A Report to the Congress on- DEVELOPMENT NEEDS and OPPORTUNITIES for COOPERATION in SOUTHERN AFRICA United States Agency for International Development/March 1979 MINING IN Trii SOUTHERN AFRICA REGION Robert M. Dean November 1978 Robert Dean Conspltants Contract afr-C-1424 TABLE OF CONTENTS page Abbreviations Used in the Report i Currency Conversions ii I INTRODUCTION 1 II MINING SECTOR ANALYSIS 3 Botswana 3 Leso ho 12 Malawi 17 Mozambique 21 Namibia 26 Swaziland 33 Zambia 39 Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) 49 III SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FOREIGN ASSISTANCE TO THE MINING SECTORS OF THE COUNTRIES OF THE SOUTHERN AFRICA REGION 54 IV GENERAL RECOM.MENDATIONS FOR U.S. ASSIST- ANCE ON A REGIONAL BASIS TO THE MINING SECTOR OF THE COUNTRIES OF THE SOUTHERN AFRICA REGION 55 CURRENCY CONVERSIONS Countrf Country Symbol Vlue* Botswana Pula P P1 - $0.90 Lesotho Rand R Ri - $1.15 Swaziland Emalangeni E El - $1.15 Malawi Kwacha K K1 - $1.13 Mozambique Escudo ES ESI - $0.03 Zimbabwe Rhodesian Dollar R$ R$1 - $1.54 Namibia Rand R RI - $1.15 Zambia Kwacha K KI - $1.33 South Africa Rand R RI - $1.15 as of 7-24-78 ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE REPORT AGIP Italian Agency for Petroleum (Italy) CDM Consolidated Diamond Mines (South Africa) CIDA Canadian International Development Agency EEC European Economic Commumity IC.T Imperial Chemical Industries (UK) INDECO Industrial Development Company .(Zambia) ISCOR South African Iron and Steel Industrial Corporation Ltd. JCI Johannesburg Chamber of Industries MINDECO Mining Development Company (Zambia) MINDEX (exploration company of MINDECO) SOEKOR (Southern Oil Exploration Corporation) (South Africa) SWAKOR (Namibian subsidiary of SOEKOR) TIKA Technical and Indistrial Kulubila Associates Ltd. -

Environmental Impacts of Mining in Zambia. Towards Better

environmental impacts of mining in zambia Towards better environmental management and sustainable exploitation of mineral resources Joanna Lindahl July 2014 SGU-rapport 2014:22 Cover: Kanshanshi copper gold mine in Solwezi, Zambia. Photo: Joanna Lindahl. Geological Survey of Sweden Box 670, SE-751 28 Uppsala Phone: +46 18 17 90 00 Fax: +46 18 17 92 10 e-mail: [email protected] www.sgu.se SUMMARY Environmental impacts from mining operations are significant and quite often severe, especially in developing nations which lack adequate management of the sector. In Zambia, impacts from mining results from both historical and ongoing mining operations, and the majority of them is located in the Copperbelt district. Recent investments in exploration and mine developments have, however, led to new operations also in other provinces. The main environmental problems associated with mines in Zambia are pollution of air, soil and water, geotechnical issues and land degradation. The contribution from old mining legacy sites have shown to be minor compared to current mining operations. The governmental framework that regulates the mining sectors environmental compliance is centered on Zambia Environmental Management Agency (ZEMA). The agency authorizes min- ing projects through an environmental impact assessment (EIA) process, issues environmental permits and is responsible for auditing. The Mine Safety Department also has governmental responsibility for the sectors environmental issues. Existing laws and regulations regarding en- vironmental performance are relatively up to date in Zambia; the main problem for the country is that the implementation is not satisfactory. Partially this is explained by lack of coordination between institutions but also to a large extent on the lack of manpower and technical capacity. -

Zambia Country Mining Guide

MINING Zambia Country mining guide kpmg.com/mining KPMG INTERNATIONAL Strategy Series © 2013 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated. © 2013 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated. Contents Executive summary 2 New geographic expansion risk framework 3 Country snapshot 4 World Bank ranking: Ease of doing business 5 Type of government 5 Economy and fiscal policy 6 Fraser Institute rankings 6 Regulatory environment 7 Sustainability and environment 9 Taxation 11 Power supply 13 Infrastructure development 14 Labor relations and employment situation 16 Inbound and outbound investment 17 Key commodities — Production and reserves 18 Mining prospects in Zambia 24 Major mining companies in Zambia 27 Foreign companies with operations in Zambia 28 Further insight from KPMG 29 Mining asset life cycle 31 KPMG’s mining strategy service offerings 31 KPMG’s Global Mining practice 32 KPMG’s footprint in Africa 33 © 2013 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated. © 2013 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated. 2 | Zambia mining guide Executive summary For 2 decades, Zambia’s mining sector has experienced significant foreign interest and investment driven mainly by the privatization of state-owned Zambia Consolidated Copper Mines (“ZCCM”), a low taxation environment and low political interference. -

Mining Rights in Zambia

MINING RIGHTS IN ZAMBIA MINING RIGHTS IN ZAMBIA Muna Ndulo LLB (Zambia) LLM (Harvard) D. Phil (Oxon) Advocate of the High Court for Zambia, Professor of Law, University of Zambia. Kenneth Kaunda Foundation Muna Ndulo, 1987 First Published 1987 by Kenneth Kaunda Foundation (Publishing and Printing Division) P. O. Box 32664, Lusaka, Zambia ISBN 9982-01-001-8 Printed in Zimbabwe by Print Holdings Dedicated to my parents Temba and Julia: They started it all. PREFACE A legal framework is required for most human endeavours, whether it be to apply justice or to establish codes of public conduct or to provide facilities for the conduct of social or economic life by regulating and thus enabling such activities to be carried out in an orderly manner. The number of these activities have proliferated considerably mostly as a result of the extraordinary industrial and social development of the world. Hence, like in all other activities legislation is required to establish rules and regulations to control mining activities. This book is an attempt to provide a detailed study of such a legal framework within which the orderly development and operations relating to the activities of mineral exploitation in Zambia are carried out. The term mining law here is used to mean those enactments which in various ways regulate the acquisition and tenure of mining rights and mining grounds, and the practice of mining-right holders. It relates primarily to the disposition of mining rights and the specific imposts that relate to the exploitation of mineral deposits. The main aspects of mining law cover such things as definition of minerals, ownership of resources, law relating to the right to mine, conditions of governing the issue and holding of mining rights, and the relationship between mineral-and surface-right holders. -

Mining Legislation and Mineral Development in Zambia Muna Ndulo

Cornell International Law Journal Volume 19 Article 1 Issue 1 Winter 1986 Mining Legislation and Mineral Development in Zambia Muna Ndulo Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Ndulo, Muna (1986) "Mining Legislation and Mineral Development in Zambia," Cornell International Law Journal: Vol. 19: Iss. 1, Article 1. Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj/vol19/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell International Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CORNELL INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL Volume 19 Winter 1986 Number 1 ARTICLE MINING LEGISLATION AND MINERAL DEVELOPMENT IN ZAMBIA Muna Ndulot TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................... 2 I. BACKGROUND ...................................... 3 A. History of Mining in Zambia ...................... 3 1. Pre-colonial trade in copper .................... 3 2. Current status of the Zambian copper industry.. 4 B. Zambia Prior to Independence ..................... 6 1. The British South African Company ............ 6 2. Mining legislation and mining development in pre-independence Zambia ...................... 7 C. Zambian Independence and the Repeal of the Old M ining System .................................... 9 t Visiting Professor, Cornell Law School, Fall 1984; Professor of Law, University of Zambia School of Law. 2 CORNELL INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 19:1 1. Acquisition of the British South African Company's mineral rights ...................... 9 2. Nationalization achieved through the Mines and M inerals Act .................................. 11 II. SOURCES OF LAW RELATING TO MINING RIG H TS .............................................