Final Boy Zine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SINCLAIR STANDS UNITED with #Sinclairstrongertogether EVENT

Page 1 April 3–9, 2018 SAAB Pg. 4 Baby Skynet Pg. 4 BanG Dream! Pg. 7 Lizzy Martinez Pg. 9 The Volume 41, Issue 26 April 17–23, 2018 www.sinclairclarion.com SINCLAIR STANDS UNITED WITH #SinclairStrongerTogether EVENT Mame Thiome Following this, Pergram told the world go round. help people in situations similar to her Henry Wolski audience about the event that spawned Throughout the event, Sinclair’s own. Executive Editor this movement of positivity across various choral groups sang pieces “...After being called names and Sinclair. connected to the theme of unity and being chased home from school Jake Conger In building 2 this past fall semester, diversity, including “Ndikhokele frequently, somewhere inside of Reporter a Clarion paper was found heavily Bawo (Keep Me Safe),” “Even When myself I decided that if I was gonna vandalized against a race of people. He is Silent” and “If Music be the be called names for being Jewish or On Tuesday, April 10, several This racist act fueled the CMA to team Food of Love.”. being a Jew, I was gonna be the best Sinclair student clubs including the up with other students across campus Following this was guest speaker Jew I could be,” Frydman said. Choral Music Association (CMA), to create a group and find a way to Renate Frydman, a Holocaust survivor She closed her part of the program Communications Club and Brite respond to and combat these acts of who has been involved with Sinclair by telling those in attendance how Signal Alliance teamed up with the negativity at Sinclair. -

Brief of Appellee Utah Court of Appeals

Brigham Young University Law School BYU Law Digital Commons Utah Court of Appeals Briefs 1996 Farmers Insurance Exchange v. David Parker : Brief of Appellee Utah Court of Appeals Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/byu_ca2 Part of the Law Commons Original Brief Submitted to the Utah Court of Appeals; digitized by the Howard W. Hunter Law Library, J. Reuben Clark Law School, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah; machine-generated OCR, may contain errors. Chad B. McKay; Attorney for Appellee. Rodney R. Parker; Snow, Christensen and Martineau; Attorneys for Appellant. Recommended Citation Brief of Appellee, Farmers Insurance Exchange v. Parker, No. 960236 (Utah Court of Appeals, 1996). https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/byu_ca2/173 This Brief of Appellee is brought to you for free and open access by BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Utah Court of Appeals Briefs by an authorized administrator of BYU Law Digital Commons. Policies regarding these Utah briefs are available at http://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/utah_court_briefs/policies.html. Please contact the Repository Manager at [email protected] with questions or feedback. UTAH COURT OF APPEALS UTAH DOCUMENT KFU 50 DOCKET NO. ^(lOTJe CA IN THE UTAH COURT OF APPEALS FARMERS INSURANCE EXCHANGE Plaintiff/Appellee Case No 960236CA vs. DAVID PARKER Argument Priority 15 Defendant/Appellant. BRIEF OF APPELLEE Appeal from Judgment Rendered By Third Judicial Circuit Court Salt Lake County, State of Utah Honorable Michael L. Hutchings, Presiding CHAD B. McKAY ( 2650 Washington Blvd, #101 Ogden, Utah 84401 Telephone : (801) 621 6021 Attorney for Appellee RODNEY R. -

Word Search Tiffany (Simon) (Dreama) Walker Conflicts Call (972) 937-3310 © Zap2it

Looking for a way to keep up with local news, school happenings, sports events and more? February 10 - 16, 2017 2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad We’ve got you covered! waxahachietx.com How Grammy V A H A D S D E A M W A H K R performances 2 x 3" ad E Y I L L P A S Q U A L E P D Your Key M A V I A B U X U B A V I E R To Buying L Z W O B Q E N K E H S G W X come together S E C R E T S R V B R I L A Z and Selling! 2 x 3.5" ad C N B L J K G C T E W J L F M Carrie Underwood is slated to A D M L U C O X Y X K Y E C K perform at the 59th Annual Grammy Awards Sunday on CBS. R I L K S U P W A C N Q R O M P I R J T I A Y P A V C K N A H A J T I L H E F M U M E F I L W S G C U H F W E B I L L Y K I T S E K I A E R L T M I N S P D F I T X E S O X F J C A S A D I E O Y L L N D B E T N Z K O R Z A N W A L K E R S E “Doubt” on CBS (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Sadie (Ellis) (Katherine) Heigl Lawyers Place your classified Solution on page 13 Albert (Cobb) (Dulé) Hill Justice ad in the Waxahachie Daily 2 x 3" ad Billy (Brennan) (Steven) Pasquale Secrets Light, Midlothian1 xMirror 4" ad and Cameron (Wirth) (Laverne) Cox Passion Ellis County Trading Post! Word Search Tiffany (Simon) (Dreama) Walker Conflicts Call (972) 937-3310 © Zap2it 2 x 3.5" ad 2 x 4" ad 4 x 4" ad 6 x 3" ad 16 Waxahachie Daily Light homa City Thunder. -

TV NATIONAL HONOREES 60 Minutes: the Chibok Girls (60

TV NATIONAL HONOREES 60 Minutes: The Chibok Girls (60 Minutes) Clarissa Ward (CNN International) CBS News CNN International News Magazine Reporter/Correspondent Abby McEnany (Work in Progress) Danai Gurira (The Walking Dead) SHOWTIME AMC Actress in a Breakthrough Role Actress in a Leading Role - Drama Alex Duda (The Kelly Clarkson Show) Fiona Shaw (Killing Eve) NBCUniversal BBC AMERICA Showrunner – Talk Show Actress in a Supporting Role - Drama Am I Next? Trans and Targeted Francesca Gregorini (Killing Eve) ABC NEWS Nightline BBC AMERICA Hard News Feature Director - Scripted Angela Kang (The Walking Dead) Gender Discrimination in the FBI AMC NBC News Investigative Unit Showrunner- Scripted Interview Feature Better Things Grey's Anatomy FX Networks ABC Studios Comedy Drama- Grand Award BookTube Izzie Pick Ibarra (THE MASKED SINGER) YouTube Originals FOX Broadcasting Company Non-Fiction Entertainment Showrunner - Unscripted Caroline Waterlow (Qualified) Michelle Williams (Fosse/Verdon) ESPN Films FX Networks Producer- Documentary /Unscripted / Non- Actress in a Leading Role - Made for TV Movie Fiction or Limited Series Catherine Reitman (Workin' Moms) Mission Unstoppable Wolf + Rabbit Entertainment (CBC/Netflix) Produced by Litton Entertainment Actress in a Leading Role - Comedy or Musical Family Series Catherine Reitman (Workin' Moms) MSNBC 2019 Democratic Debate (Atlanta) Wolf + Rabbit Entertainment (CBC/Netflix) MSNBC Director - Comedy Special or Variety - Breakthrough Naomi Watts (The Loudest Voice) Sharyn Alfonsi (60 Minutes) SHOWTIME -

La Marche Des Morts

1 La marche des morts Au commencement, il y avait un livre. Au commence- ment, il y a toujours un livre. Le comic book The Walking Dead paraît pour la première fois en 2003. D’abord pressenti pour être une bande dessinée de science-fiction sur fond d’invasion zombie et portant le joli nom de Dead Planet, le projet est revu et corrigé à maintes reprises. L’aspect SF est remisé au placard, et le cadre de l’histoire nous plonge dans une époque contemporaine, à ceci près qu’une épidémie galopante a transformé une très grande partie de l’humanité en zombies. Très vite, l’œuvre en noir et blanc remporte un énorme succès. Pensez donc, le premier numéro de la BD sorti en 2003 à seulement 7300 exemplaires est aujourd’hui vendu à plus de 10 000 euros. Les chiffres de vente donnent le vertige. Le numéro 100, édité avec 10 couvertures diffé- rentes, s’est vendu à près de 400 000 exemplaires rien qu’aux États-Unis. En France aussi, le phénomène TWD affole les compteurs. Tous les spécialistes le confirment : c’est le grand hit comics des 15 dernières années. Bien que 7 THE WALKING DEAD DÉCRYPTÉ TWD ne soit arrivé dans l’Hexagone qu’en 2007, chaque tome est aujourd’hui édité à plus de 100 000 exemplaires. Plus de 2 millions d’albums ont été écoulés en moins de 10 ans, et la licence représente près de la moitié des ventes de comics dans notre pays. Rien qu’en 2013, le numéro 1 a été acquis par plus de 50 000 curieux. -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Walking Dead: Book 8 Free Ebook

FREEWALKING DEAD: BOOK 8 EBOOK Charlie Adlard,Robert Kirkman,Sina Grace | 336 pages | 09 Oct 2012 | Image Comics | 9781607065937 | English | Fullerton, United States The Walking Dead AMC's 'The Walking Dead' is full of incredible characters. Some of them just happen to be incredibly annoying and terrible. One of The Walking Dead‘s most consistently strong points is its incredible ensemble. Throughout the past seven seasons, fans have enjoyed an incredible ride with good guys and. AMC's The Walking Dead is one of the most popular shows on TV, but we bet you didn't know these 5 surprising facts about the series. Full of great characters, flesh-craving zombies, and tales of fighting for survival, it’s no surprise that AMC’s The Walking Dead has developed a huge cult following. Rick and his group of survivors have been through a lot, and not just with the walkers. There are terrible humans out there, some trying to take and control what they shouldn't. So who from the action-packed world of the "Walking Dead" are you? ENTERTAINMENT By: Khadija Leon 5 Min Quiz Rick and his. Everything we know about what's next for 'The Walking Dead' and 'Fear the Walking Dead' Nurse your emotional wounds and celebrate the narrowing survival of your favorite post-apocalyptic characters with comfort food bites for humans and zombies alike. Delish editors handpick every product we feature. We may earn commission from the links on this page. It's finally, finally here — the r. A few years ago it seemed that The Walking Dead would outlive us all—but on Wednesday Scott Gimple and Angela Kang confirmed that the onetime TV juggernaut will come to an end with a episode 11th season. -

Behind the Scenes: Uncovering Violence, Gender, and Powerful Pedagogy

Behind the Scenes: Uncovering Violence, Gender, and Powerful Pedagogy Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy Volume 5, Issue 3 | October 2018 | www.journaldialogue.org e Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy INTRODUCTION AND SCOPE Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy is an open-access, peer-reviewed journal focused on the intersection of popular culture and pedagogy. While some open-access journals charge a publication fee for authors to submit, Dialogue is committed to creating and maintaining a scholarly journal that is accessible to all —meaning that there is no charge for either the author or the reader. The Journal is interested in contributions that offer theoretical, practical, pedagogical, and historical examinations of popular culture, including interdisciplinary discussions and those which examine the connections between American and international cultures. In addition to analyses provided by contributed articles, the Journal also encourages submissions for guest editions, interviews, and reviews of books, films, conferences, music, and technology. For more information and to submit manuscripts, please visit www.journaldialogue.org or email the editors, A. S. CohenMiller, Editor-in-Chief, or Kurt Depner, Managing Editor at [email protected]. All papers in Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy are published under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share- Alike License. For details please go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/. Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy EDITORIAL TEAM A. S. CohenMiller, PhD, Editor-in-Chief, Founding Editor Anna S. CohenMiller is a qualitative methodologist who examines pedagogical practices from preK – higher education, arts-based methods and popular culture representations. -

I "I)I WW" the New Orzleans Review

.\,- - i 1' i 1 i "I)i WW" the new orzleans Review LOYOLA UNIVERSITY A Iournal of Literature Vol. 5, No.2 & Culture Published by Loyola University table of contents of the South New Orleans articles Thomas Merton: Language and Silence/Brooke Hopkins .... Editor: $ Jesus and Jujubes/Roger Gillis . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Marcus Smith I v fiction Managing Editor: Tom Bell The Nuclear Family Man and His Earth Mother Wife Come to Grips with the Situation/Otto R. Salassi .... .. .... .. .. .... .. .. Associate Editors: The Harvesters/Martha Bennett Stiles .. .. .. ... .. ....... Peter Cangelosi Beautiful Women and Glorious Medals/Barbara de la Cuesta .. Iohn Christman Dawson Gaillard interviews Lee Gary Link in the Chain of Feeling/An Interview with Anais Nin . .. .. .. Shael Herman A Missionary of Sorts/An Interview with Rosemary Daniell . .. .. I‘. HID BLISS ' 0 QQI{Q photography Advisory Editsrs= Portfolio/Ed Metz .. .... ..... ..... ..... .... ... ... ... David Daiches $'4 >' liZ‘1iiPéZ‘§Zy P°°"Y Joseph Frrhrerr Sf I Why is it that children/Brooke Hopkins ..... ... .. .. ... .. .. A_ $_]_ . .. ... .. .. .. Ioseph Tetlowr $ { ‘ Definition of God/R. P. Lawry . .. ..... .. .. The Unknown Sailor/Miller Williams .... .. .. ... .. ........ .. Editor-at-Large: .. .. $ ' For Fred Carpenter Who Died in His Sleep/Miller Williams . Alexis Gonzales, F.S.C. ' ‘ There Was a Man Made Ninety Million Dollars/Miller Williams .. ' For Victor Jara/Miller Williams ... .. .... ... ........ .... ... ... .. Ed‘r‘r%"?1 ."‘SSg°‘§‘e= ' An Old Man Writing/Shelley Ehrlich ...... .. .. ..... ... .. ... .. $ rlstina g en v Poem/Everette Maddox . .... .. .... .. ..... .. .. .. ... ... .. Th O 1 R . b_ . .. .. ... ... .. ’Q {.' Publication/Everette Maddox . .... ....... .... 1r§hI:r(muarrr(:r‘:{1rfbr?‘£1r(;r:ri§ %L:rr_ Tlck Tock/Everette Maddox .... .. .............. .. .. .. .. ... versityr New Orleans { .. .. .. ...... ... ...... ... ........ .. .. ... l ' $ ’ In Praise of Even Plastic/John Stone Subscription rate: $1.50 per 0 Bringing Her Home/John Stone ... -

The Walking Dead: Volume 26: Call to Arms Free Ebook

FREETHE WALKING DEAD: VOLUME 26: CALL TO ARMS EBOOK Charlie Adlard,Stefano Gaudiano,Robert Kirkman | 136 pages | 20 Sep 2016 | Image Comics | 9781632159175 | English | Fullerton, United States The Walking Dead AMC's The Walking Dead is one of the most popular shows on TV, but we bet you didn't know these 5 surprising facts about the series. Full of great characters, flesh-craving zombies, and tales of fighting for survival, it’s no surprise that AMC’s The Walking Dead has developed a huge cult following. A few years ago it seemed that The Walking Dead would outlive us all—but on Wednesday Scott Gimple and Angela Kang confirmed that the onetime TV juggernaut will come to an end with a episode 11th season. Once upon a time, The Walking Dead was planned to run for 12 seasons at least. Over the years. The Walking Dead is a cultural phenomenon and as such has a lot of games made about it. This game though is going to get you up close and personal in VR. Check out The Walking Dead: Onslaught Verizon BOGO Alert! Get two Galaxy S20+ for $15/mo with a new Unlimited line We may earn a commission for pu. The Worst Characters on ‘The Walking Dead’ Rick and his group of survivors have been through a lot, and not just with the walkers. There are terrible humans out there, some trying to take and control what they shouldn't. So who from the action-packed world of the "Walking Dead" are you? ENTERTAINMENT By: Khadija Leon 5 Min Quiz Rick and his. -

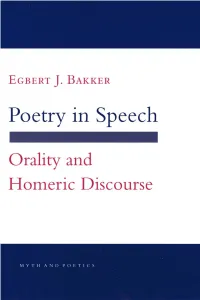

POETRY in SPEECH a Volume in the Series

POETRY IN SPEECH A volume in the series MYTH AND POETICS edited by GREGORY NAGY A fu lllist of tides in the series appears at the end of the book. POETRY IN SPEECH Orality and Homeric Discourse EGBERT J. BAKKER CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS ITHACA AND LONDON Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Copyright © 1997 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850, or visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. First published 1997 by Cornell University Press Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bakker, Egbert J. Poetry in speech : orality and Homeric discourse / Egbert J. Bakker. p. cm. — (Myth and poetics) Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN-13: 978-0-8014-3295-8 (cloth) — ISBN-13: 978-1-5017-2276-9 (pbk.) 1. Homer—Criticism and interpretation. 2. Epic poetry, Greek—History and criticism. 3. Discourse analysis, Literary. 4. Oral formulaic analysis. 5. Oral tradition—Greece. 6. Speech in literature. 7. Poetics. I. Title. PA4037.B33 1996 883'.01—dc20 96-31979 The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Contents Foreword, by Gregory Nagy -

Titles Ordered August 20 - 27, 2021

Titles ordered August 20 - 27, 2021 Blu-Ray Adventure Blu-Ray Release Date: Clarke, Emilia Above suspicion / produced by Angela Amato-Velez, http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1696655 5/18/2021 Amy Adelson, Colleen Camp, Tim Degraye, Mohamed AlRafi ; screenplay by Chris Gerolmo ; directed by Phillip Noyce. Heughan, Sam SAS: red notice / producers, Kwesi Dickson, Laurence http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1696659 6/15/2021 Malkin, Andy McNab, Joe Simpson ; screenplay by Laurence Malkin ; directed by Magnus Martens. Rose, Ruby Vanquish / produced by Richard Salvatore, David E. http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1696656 4/27/2021 Ornston, Nate Adams ; written by George Gallo, Samuel Bartlett ; directed by George Gallo. Comedy Blu-Ray Release Date: Uy, Alain The paper tigers / produced by Al'n Duong, Yuji http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1696654 6/22/2021 Okumoto, Quoc Bao Tran, Michael Velasquez, Ron Yuan ; written and directed by Quoc Bao Tran. Drama Blu-Ray Release Date: Cumberbatch, Benedict The Mauritanian / produced by Adam Ackland, Leah http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1696650 5/11/2021 Clarke, Benedict Cumberbatch, Lloyd Levin, Beatriz Levin [and others] ; screenplay by M.B. Traven, Rory Haines, Sohrab Noshirvani ; directed by Kevin Macdonald. Depp, Johnny City of lies / producers, Paul M. Brennan, Stuart http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1696652 6/8/2021 Manashil, Miriam Segal ; screenplay, Christian Contreras ; directed by Brad Furman. Duvall, Robert 12 mighty orphans / produced by Brinton Bryan, http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1696653 8/31/2021 Angelique De Luca, Michael De Luca, Houston Hill, Ty Roberts ; screenplay by Kevin Meyer, Ty Roberts ; directed by Ty Roberts.