Dental and Medical Problems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Establishment of a Dental Effects of Hypophosphatasia Registry Thesis

Establishment of a Dental Effects of Hypophosphatasia Registry Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jennifer Laura Winslow, DMD Graduate Program in Dentistry The Ohio State University 2018 Thesis Committee Ann Griffen, DDS, MS, Advisor Sasigarn Bowden, MD Brian Foster, PhD Copyrighted by Jennifer Laura Winslow, D.M.D. 2018 Abstract Purpose: Hypophosphatasia (HPP) is a metabolic disease that affects development of mineralized tissues including the dentition. Early loss of primary teeth is a nearly universal finding, and although problems in the permanent dentition have been reported, findings have not been described in detail. In addition, enzyme replacement therapy is now available, but very little is known about its effects on the dentition. HPP is rare and few dental providers see many cases, so a registry is needed to collect an adequate sample to represent the range of manifestations and the dental effects of enzyme replacement therapy. Devising a way to recruit patients nationally while still meeting the IRB requirements for human subjects research presented multiple challenges. Methods: A way to recruit patients nationally while still meeting the local IRB requirements for human subjects research was devised in collaboration with our Office of Human Research. The solution included pathways for obtaining consent and transferring protected information, and required that the clinician providing the clinical data refer the patient to the study and interact with study personnel only after the patient has given permission. Data forms and a custom database application were developed. Results: The registry is established and has been successfully piloted with 2 participants, and we are now initiating wider recruitment. -

Hyperdontia: 3 Cases Reported Dentistry Section

Case Report Hyperdontia: 3 Cases Reported Dentistry Section SUJATA M. BYAHATTI ABSTRACT In some cases, there appears to be a hereditary tendency for A supernumerary tooth may closely resemble the teeth of the the development of supernumerary teeth. A supernumerary group to which it belongs, i.e molars, premolars, or anterior tooth is an additional entity to the normal series and is seen in all teeth, or it may bear little resemblance in size or shape to the quadrants of the jaw. teeth with which it is associated. It has been suggested that The incidence of these teeth is not uncommon. Different variants supernumerary teeth develop from a third tooth bud which of supernumerary teeth are discussed and reviewed in detail in arises from the dental lamina near the permanent tooth bud, the following article. or possibly from the splitting of the permanent tooth bud itself. Key Words: Supernumerary teeth, Mesiodens, Upper distomolar INTRODUCTION The extraction of these teeth is a general rule for avoiding A supernumerary tooth (or hyperodontia) is defined as an increase complications [15]. Nevertheless, some authors such as Koch in the number of teeth in a given individual, i.e., more than 20 et al [20] do not recommend the extractions of impacted teeth in deciduous or temporary teeth and over 32 teeth in the case of the children under 10 years of age, since in this particular age group, permanent dentition [1], [2]. such procedures often require general anaesthesia. Kruger [21] considers that the extraction of supernumerary teeth should be Supernumerary teeth are a rare alteration in the development of postponed until the apexes of the adjacent teeth have sealed. -

Dental Number Anomalies and Their Prevalence According to Gender and Jaw in School Children 7 to 14 Years

ID Design Press, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2018 May 20; 6(5):867-873. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2018.174 eISSN: 1857-9655 Dental Science Dental Number Anomalies and Their Prevalence According To Gender and Jaw in School Children 7 To 14 Years Milaim Sejdini1*, Sabetim Çerkezi2 1Clinic of Orthodontics, University Clinic of Dentistry, Medical Faculty, University of Prishtina, Prishtina, Kosovo; 2Faculty of Medical Sciences, State University of Tetovo, Tetovo, Republic of Macedonia Abstract Citation: Sejdini M, Çerkezi S. Dental Number OBJECTIVES: This study aimed to find the prevalence of Hypodontia and Hyperdontia in different ethnicities in Anomalies and Their Prevalence According To Gender patients from 7 to 14 years old. and Jaw in School Children 7 To 14 Years. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018 May 20; 6(5):867-873. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2018.174 MATERIAL AND METHODS: A group of 520 children were included aged 7 to 14 years, only the children who Keywords: Hypodontia; Hyperdontia; ethnics; children went to primary schools. Controls were performed by professional people to preserve the criteria of orthodontic *Correspondence: Milaim Sejdini. Clinic of Orthodontics, abnormalities evaluation. The data were recorded in the individual card specially formulated for this research and University Clinic of Dentistry, Medical Faculty, University all the patients suspected for hypodontia and hyperdontia the orthopantomography for confirmation was made. of Prishtina, Prishtina, Kosovo. E-mail: [email protected] The data were analysed using descriptive statistical analysis using 2 test for the significant difference for p ˂ 0.05 and Fisher test for p < 0.05. -

DLA 2220 Oral Pathology

ILLINOIS VALLEY COMMUNITY COLLEGE COURSE OUTLINE DIVISION: Workforce Development COURSE: DLA 2220 Oral Pathology Date: Spring 2021 Credit Hours: 0.5 Prerequisite(s): DLA 1210 Dental Science II Delivery Method: Lecture 0.5 Contact Hours (1 contact = 1 credit hour) Seminar 0 Contact Hours (1 contact = 1 credit hour) Lab 0 Contact Hours (2-3 contact = 1 credit hour) Clinical 0 Contact Hours (3 contact = 1 credit hour) Online Blended Offered: Fall Spring Summer CATALOG DESCRIPTION: The field of oral pathology will be studied, familiarizing the student with oral diseases, their causes (if known), and their effects on the body. A dental assistant does not diagnose oral pathological diseases, but may alert the dentist to abnormal conditions of the mouth. This course will ensure a basic understanding of recognizing abnormal conditions (anomalies), how to prevent disease transmission, how the identified pathological condition may interfere with planned treatment, and what effect the condition will have on the overall health of the patient. Curriculum Committee – Course Outline Form Revised 12/5/2016 Page 1 of 9 GENERAL EDUCATION GOALS ADDRESSED [See last page for Course Competency/Assessment Methods Matrix.] Upon completion of the course, the student will be able: [Choose up to three goals that will be formally assessed in this course.] To apply analytical and problem solving skills to personal, social, and professional issues and situations. To communicate successfully, both orally and in writing, to a variety of audiences. To construct a critical awareness of and appreciate diversity. To understand and use technology effectively and to understand its impact on the individual and society. -

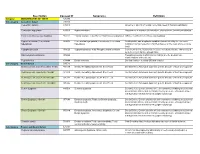

Neurofibromatosis Type I and Supernumerary Teeth: Up-To Date Review and Case Report

Med Buccale Chir Buccale 2017;23:84-89 www.mbcb-journal.org © Les auteurs, 2016 DOI: 10.1051/mbcb/2016041 Up-to date Review and Case Report Neurofibromatosis type I and supernumerary teeth: up-to date review and case report Charline Cervellera1,*, David Del Pin2, Caroline Dissaux3 1 Intern in Oral Surgery, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department, Hôpital Pasteur, Colmar, France 2 MD, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department, Hôpital Pasteur, Colmar, France 3 MD, Plastic Reconstructive, Aesthetic and Maxillofacial Surgery Department, Strasbourg University Hospital, Strasbourg, France (Received 19 July 2016, accepted 26 August 2016) Key words: Abstract – Introduction: Neurofibromatosis type I (NF1) is a genetic disease that may involve oral manifestations neurofibromatosis such as supernumerary teeth. Case report: A 17-year-old male patient with NF1 was referred by an orthodontist for type 1 / genetic avulsion of wisdom teeth and six supernumerary teeth. Ten teeth were removed under general anesthesia in disease / therapeutic December 2015. Discussion: Management of supernumerary teeth is very controversial and patient care of NF1 is decision making / complex. Conclusion: Even though the presence of supernumerary teeth in cases of NF1 is not well-known, patient supernumerary teeth care is extremely important and requires a team of specialists. Mots clés : Résumé – Les dents surnuméraires dans la neurofibromatose de type I : cas clinique et revue de la littéra- neurofibromatose ture. Introduction : La neurofibromatose de type I est une maladie génétique qui peut induire des manifestations de type i / maladie orales comme la présence de dents surnuméraires. Observation clinique : Un homme de 17 ans présentant une génétique / décision NF1 a été adressé par son orthodontiste pour l’avulsion de ses dents de sagesse et 6 dents surnuméraires. -

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition Category ABNORMALITIES OF TEETH 426390 Subcategory Cementum Defect 399115 Cementum aplasia 346218 Absence or paucity of cellular cementum (seen in hypophosphatasia) Cementum hypoplasia 180000 Hypocementosis Disturbance in structure of cementum, often seen in Juvenile periodontitis Florid cemento-osseous dysplasia 958771 Familial multiple cementoma; Florid osseous dysplasia Diffuse, multifocal cementosseous dysplasia Hypercementosis (Cementation 901056 Cementation hyperplasia; Cementosis; Cementum An idiopathic, non-neoplastic condition characterized by the excessive hyperplasia) hyperplasia buildup of normal cementum (calcified tissue) on the roots of one or more teeth Hypophosphatasia 976620 Hypophosphatasia mild; Phosphoethanol-aminuria Cementum defect; Autosomal recessive hereditary disease characterized by deficiency of alkaline phosphatase Odontohypophosphatasia 976622 Hypophosphatasia in which dental findings are the predominant manifestations of the disease Pulp sclerosis 179199 Dentin sclerosis Dentinal reaction to aging OR mild irritation Subcategory Dentin Defect 515523 Dentinogenesis imperfecta (Shell Teeth) 856459 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield I 977473 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield II 976722 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; -

Major Salivary Gland Aplasia and Hypoplasia in Down Syndrome

CASE REPORT Major salivary gland aplasia and hypoplasia in Down syndrome: review of the literature and report of a case Mary Jane Chadi1 , Guy Saint Georges2, Francine Albert2, Gisele Mainville1, Julie Mi Nguyen1 & Adel Kauzman1 1Faculty of Dentistry, Universite de Montreal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada 2Private practice, Laval, Quebec, Canada Correspondence Key Clinical Message Adel Kauzman, Faculty of Dentistry, Universite de Montreal, PO box 6128, Salivary gland aplasia and hypoplasia are rarely described in the medical litera- Centre-ville station, Montreal, Qc, H3C 3J7 ture. This article presents a case of aplasia and hypoplasia of the major salivary Canada. Tel: +1 514-343-6081; glands in a patient with Down syndrome. A literature review, as well as an Fax: +1 514-343-2233; overview of the diagnosis and management of this condition, is presented. E-mail: [email protected] Keywords Funding Information Congenital abnormalities, Down syndrome, parotid gland, salivary glands, No sources of funding were declared for this tooth wear, xerostomia. study. Received: 11 October 2016; Revised: 21 March 2017; Accepted: 22 March 2017 Clinical Case Reports 2017; 5(6): 939–944 doi: 10.1002/ccr3.975 Introduction The parotid glands produce almost exclusively serous saliva and are most active during salivary flow stimula- Aplasia and hypoplasia of the major salivary glands are tion. Parotid secretion accounts for more than 50% of rare developmental anomalies. They can be isolated or stimulated saliva and only 28% of unstimulated saliva part of a syndrome, as well as unilateral or bilateral. They [4]. The submandibular gland produces mixed saliva with can affect more than one of the major glands [1, 2]. -

DAPA 741 Oral Pathology Examination 4 December 6, 2000 1

Name: _____________________ DAPA 741 Oral Pathology Examination 4 December 6, 2000 1. Irregularity of the temporomandibular joint surfaces is a radiographic feature of A. Subluxation B. Osteoarthritis C. Trigeminal neuralgia D. Anterior disk displacement 2. Which of the following is an autoimmune disease? A. Bell’s palsy B. Osteoarthritis C. Rheumatoid arthritis D. Trigeminal neuralgia 3. Which joints are commonly affected in osteoarthritis but usually spared in rheumatoid arthritis? A. Hips B. Joints of the hands C. Knees D. Temporomandibular joint 4. Bell’s palsy may be induced by trauma to which nerve? A. Trigeminal nerve B. Glossopharyngeal nerve C. Facial nerve D. Inferior alveolar nerve 5. A patient presents to your office concerned about a painless click when she open her mouth. Your examination of her temporomandibular joint reveals a click at approximately 15 mm of opening. You instruct her to touch the incisal edges of her maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth together and then open from this position. The click disappears when she opens from this position. You diagnosis is A. Subluxation B. Anterior disk displacement C. Crepitus D. Inflammatory arthralgia 6. An ankylosed joint will cause the mandible to deviate to which side on opening? A. The affected side B. The unaffected side C. There would be no deviation on opening 7. Pain from which of the following commonly awakens the patient at night? A. Masticatory myofascial pain B. Tension headaches C. Trigeminal neuralgia D. Osteoarthritis 8. Which of the following disorders may result in blindness and is thus considered an acute ocular emergency? A. Trigeminal neuralgia B. -

Dantal College Inner Pages Vol-6.Cdr

ISSN 0976-2256 E-ISSN: 2249-6653 The journal is indexed with ‘Indian Science Abstract’ (ISA) (Published by National Science Library), www.ebscohost.com, www.indianjournals.com JADCH is available (full text) online: Website- www.adc.org.in/html/viewJournal.php This journal is an official publication of Ahmedabad Dental College and Hospital, published bi-annually in the month of March and September. The journal is printed on ACID FREE paper. Editor - in - Chief Dr. Darshana Shah Co - Editor Dr. Rupal Vaidya Assistant Editor: Dr. Harsh Shah Editorial Board: DENTISTRY TODAY... Dr. Mihir Shah Welcome to the new era of digital imaging! Today, the Dr. Vijay Bhaskar conventional imaging modalities like radiographic films and chemical processing are replaced by digital sensors with Dr. Monali Chalishazar digital processing. The conventional film based OPG machines Dr. A. R. Chaudhary have also been made obsolete by the high resolution digital OPG machines. Furthermore, medical CT and Dentascan have Dr. Neha Vyas been replaced by the latest CBCT (Cone Beam Computed Dr. Sonali Mahadevia Tomography) machines in private imaging centresrun by oral Dr. Shraddha Chokshi and maxillofacial radiologists across the country. The day is not far when the 3 dimensional CBCT imaging with a low Dr. Bhavin Dudhia patient radiation dose will be usedroutinely for cases of Dr. M Ganesh complicated / repeat RCT, maxillo-facial trauma, impacted third molars, oro-facial cysts and tumours, periodontal Dr. Mahadev Desai pathologies, orthodontic treatment planning and even Dr. Darshit Dalal scanning for CAD CAM fixed prosthodontics. The need has arisen for more and more professionals dedicated exclusively to the field of oral and maxillofacial radiology. -

The Retromolar Space and Wisdom Teeth in Humans: Reasons for Surgical Tooth Extraction

Published online: 2020-09-03 THIEME Original Article 117 The Retromolar Space and Wisdom Teeth in Humans: Reasons for Surgical Tooth Extraction Abed El Kaseh1 Maher Al Shayeb1 Syed Kuduruthullah2 Nadeem Gulrez2 1Surgical Science Department, Ajman University, Ajman, Address for correspondence Dr. Maher Al Shayeb, DDS, Msc United Arab Emirates (Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery), Surgical Science Department, 2Basic Medical Science Department, Ajman University, Ajman, Ajman University, Ajman, United Arab Emirates United Arab Emirates (e-mail: [email protected]). Eur J Dent:2021;5:117–121 Abstract Objective This article explores the problem of developing pathologies in the ret- romolar region. Findings can serve a framework for disease prevention and for the improvement of the quality of life of patients. The present study aims to justify the possibility of utilizing morphometric methods to foresee problems in the eruption of third molars. Materials and Methods A comprehensive morphometric study of the lower jaw and facial skeleton involves 100 skulls of Homo sapiens to identify the anatomical causes of problems with wisdom teeth eruption. All said skulls are divided in two groups: I: skulls with intact dentition; II: skulls with impacted third molars. Keywords Results This work allows detecting abnormalities in the eruption of the third molar ► impaction with high probability of success. The abnormalities in point are considered not only ► lower jaw those associated with the generally accepted parameters but also those that occur in retromolar space the leptoprosopic face cases. ► ► third molar Conclusions Face type and the structural features of the facial skeleton play a signif- ► wisdom teeth icant role in the abnormal eruption of the lower third molar. -

Supernumerary Teeth – Literature Review

Journal of Pre-Clinical and Clinical Research 2020, Vol 14, No 1, 18-21 www.jpccr.eu REVIEW ARTICLE Supernumerary Teeth – Literature Review Kamil Tworkowski1,A-B,D-F , Ewelina Gąsowska1,B,D , Dorota Baryła1,C-D , Katarzyna Gabiec2,E-F 1 Student Research Group “StuDentio”, Department of Dentistry Propaedeutics, Medical University, Bialystok, Poland 2 Private Practice Lux-Dent Stomatologia, Bialystok, Poland A – Research concept and design, B – Collection and/or assembly of data, C – Data analysis and interpretation, D – Writing the article, E – Critical revision of the article, F – Final approval of article Tworkowski K, Gąsowska E, Baryła D, Gabiec K. Supernumerary Teeth – Literature Review. J Pre-Clin Clin Res. 2020; 14(1): 18–21. doi: 10.26444/jpccr/119037 Abstract Introduction and objective. Hyperdontia is a developmental anomaly characterised by an increased number of dental buds. It is condition with a prevalence of 0.3 -1.8% in primary dentition and 1.5–3.9% in permanent dentition. The abnormality occurs more often in the jaw, in anterior region and in permanent dentition. This study aimed to review current literature and present the aetiology, prevalence, diagnosis, treatment options and complications of supernumerary teeth. State of knowledge. Supernumerary teeth can be divided according to different criteria: by structure, tooth shape, location and number of additional teeth. The most common supernumerary tooth is mesiodens, which is an additional tooth located between the central incisors of the jaw. The aetiology of formation of supernumerary teeth is not yet fully known. At present, the most probable hypothesis for the development of hyperdontia is the hyperactivity of dental lamina. -

Hypo-Hyperdontia: a Case Report

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1981-863720150003000121063 ORIGINAL | ORIGINAL Hypo-hyperdontia: a case report Hipo-hiperdontia: relato de caso Henrique Castilhos RUSCHEL1 Michelle DIAMANTE1 Paulo Floriani KRAMER1 ABSTRACT The occurrence of hypodontia (absence of teeth) and hyperdontia (presence of supernumerary teeth) in the same patient is a rarely seen condition in dental practice. Early diagnosis and adequate treatment are very important when addressing this abnormality in the mixed dentition. The approach will depend on the severity of the case and the timing of diagnosis. This paper reports the case of an 11-year-old patient with absence of the permanent maxillary lateral incisors and the mandibular second premolars, with concomitant presence of a supernumerary tooth in the region of the right mandibular lateral incisor. Based on physical and radiographic examination findings, a diagnosis of hypo-hyperdontia was made. The diagnostic and therapeutic management of the case is discussed. The treatment adopted was surgical removal of the supernumerary teeth and esthetic restoration to transform the permanent mandibular canines into lateral incisors. Indexing terms: Anodontia. Tooth abnormalities. Tooth, supernumerary. RESUMO A ocorrência de hipodontia - ausência de dentes - e hiperdontia - presença de dentes a mais - em um mesmo paciente é uma condição pouco freqüente na clínica odontológica. O diagnóstico precoce e a realização de um tratamento adequado são muito importantes para a abordagem deste tipo de anomalia na dentição mista. A abordagem dependerá da complexidade de cada caso e do momento de diagnóstico da condição. Nesse artigo é relatado um caso de uma paciente com 11 anos de idade com a ausência dos incisivos laterais permanentes superiores e dos segundos pré-molares inferiores, concomitante com a presença de um dente supranumerário na região de incisivo lateral superior direito.