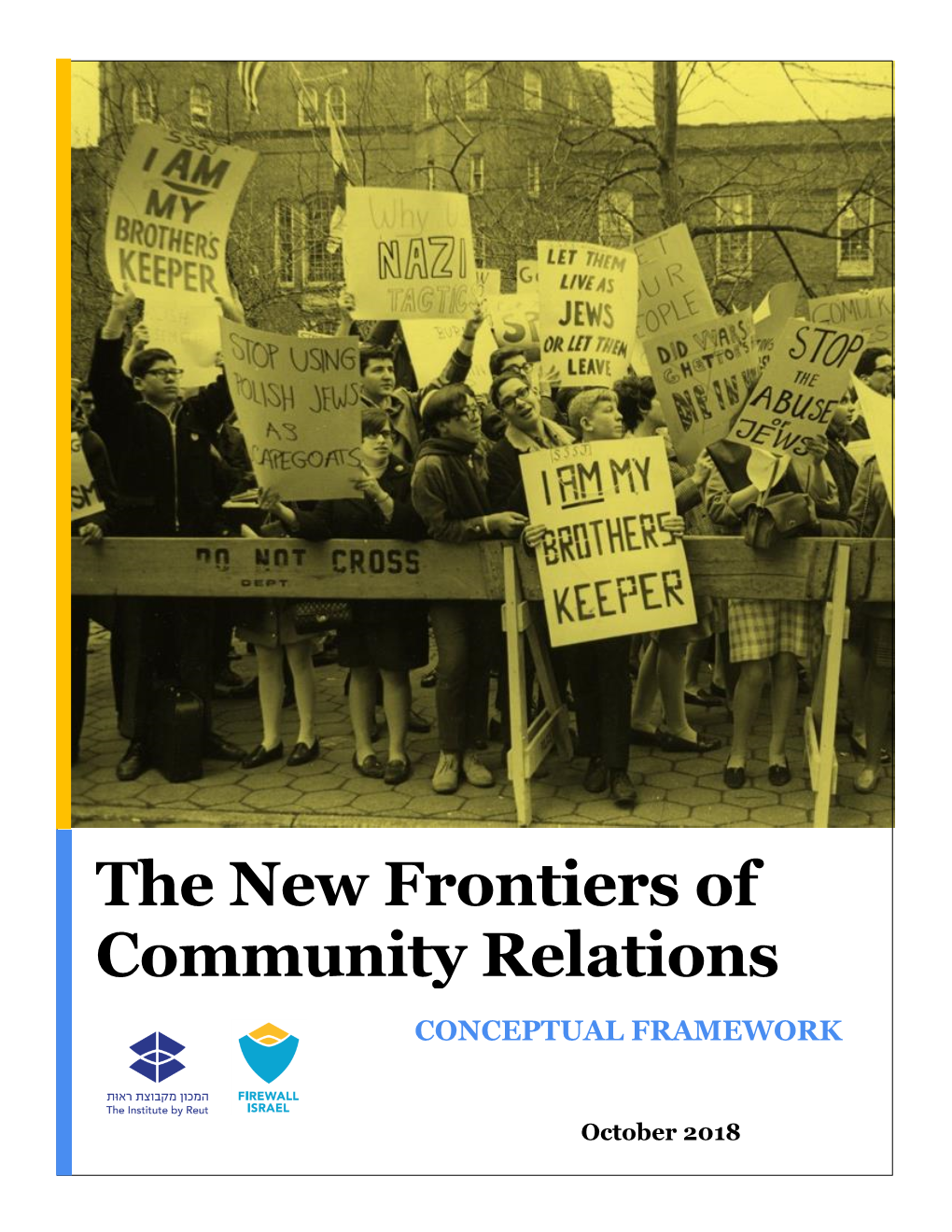

The New Frontiers of Community Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AMERICAN P VERSIGHT

AMERICAN p VERSIGHT January11,2021 VIA ONLINE PORTAL DouglasHibbard Chief,InitialRequestStaff OfficeofInform ationPolicy DepartmentofJustice 441GStNW,6thFloor Washington,DC20530 ViaOnlinePortal Re: Expedited Freedom of Information Act Request DearFOIAOfficer: PursuanttotheFreedomof InformationAct(FOIA),5U.S.C.§552,andthe implem entingregulationsof youragency,Am ericanOversightmakesthefollowing requestforrecords. OnJanuary6,2021,PresidentTrumpinciteda mtoob attackCongresswhile mbers em werecertifyingtheelectionforPresident-electJoeBiden. 1 Theapparent insurrectionistsattackedtheCapitolBuilding,forcedtheirwaypastreportedly understaffedCapitolPolice,andultim atelydelayedtheCongressionalsessionbyforcing lawmakersandtheirstaffstoflee. 2 Fourpeoplediedduringthisassaultandafifth person,aCapitolPoliceofficer,diedthefollowingdayfrominjuriesincurredwhile engagingwithrioters. 3 Whilem ilitia mbers em roamedthehallsofCongress,Trum preportedlyfoughtagainst deployingtheD.C.NationalGuard, 4 andtheDefenseDepartm entreportedlyinitially 1 PressRelease,OfficeofSen.MittRom ney,Rom neyCondemInsurrectionatU.S. ns Capitol, Jan.6,2021, https://www.romney.senate.gov/rom ney-condem ns-insurrection- us-capitol. 2 RebeccaTan,etal., TrumpSupportersStormU.S.Capitol,WithOneWomanKilledand TearGasFired, Wash.Post(Jan.7,2021,12:30AM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/trum p-supporters-storm -capitol- dc/2021/01/06/58afc0b8-504b-11eb-83e3-322644d82356 story.html. 3 EricLevenson, WhatWeKnowAboutthe5DeathsinthePro-TrumpMobthatStormedthe Capitol, CNN(Jan.8,2021,5:29PM), -

What They're Saying About Amazon's Long Island City HQ2 Announcement

Date: November 14, 2018 Contact: [email protected] What They’re Saying About Amazon’s Long Island City HQ2 Announcement “I also don’t understand why a company as rich as Amazon would need nearly $2 billion in public money.” New York Post Editorial Board: “Sure looks like Amazon’s Jeff Bezos just fleeced Gov. Andrew Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio as rubes.” “New York is offering vastly more than Virginia for its half of the new Amazon headquarters. What’s up with that? The city and state ponied up nearly $3 billion in grants, credits and so on over 25 years. Down south, Amazon is getting $573 million plus $195 million in infrastructure upgrades. Sure looks like Amazon’s Jeff Bezos just fleeced Gov. Andrew Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio as rubes.” (Editorial Board, New York Post, “The Amazon deal is no win for New Yorkers,” 11.13.2018) Governor Cuomo and New Yorkers paid “more than twice what the other supposed headquarters are paying.” “A company like Amazon could present an opportunity to collect more taxes to fix the crumbling foundation. Instead, Governor Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio made a deal with Jeff Bezos that cost the city more than twice what the other supposed headquarters are paying.” (Cale Guthrie Weissman, Fast Company, “New York got played by Amazon,” 11.13.18) Virginia taxpayers paid "about half of the $61,000 per job that Amazon said it will receive from New York to create the same number of jobs at the site in Long Island City in Queens." "Virginia’s state and local governments agreed to shell out as much as $796 million in tax incentives and infrastructure improvements over the next 15 years in exchange for 25,000 well- paying tech jobs. -

Ω Report on New York State Joint Legislative Hearings

Ω REPORT ON NEW YORK STATE JOINT LEGISLATIVE HEARINGS ON SEXUAL HARASSMENT Senator Alessandra Biaggi Chair of Committee on Ethics and Internal Governance Senator Julia Salazar Chair of Committee on Women’s Health Senator James Skoufis Chair of Committee on Investigations and Government Operations DATE OF HEARING: February 13, 2019 DATE OF REPORT: April 15, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Summary of Testimony from the February 13 Albany Hearing 3. Summary of Legislation Already Submitted 4. Comparison of Policies of the Legislature 5. Plan for Future Hearings Appendix A. Legislation Already Submitted Appendix B. Senate Sexual Harassment Policy Appendix C. Assembly Sexual Harassment Policy Appendix D. Submitted Testimony 2 1. INTRODUCTION For the first time in 27 years, on Wednesday, February 13, 2019, joint public hearings of the New York State legislature were held on the subject of Sexual Harassment in the Workplace. February’s hearing was convened in response to a troubling pattern of high rates of persistent and continuing harassing behavior over the past quarter century. More currently and specifically, the hearing was an outgrowth of and response to the courageous efforts of seven former New York State legislative employees who witnessed, reported, or experienced sexual harassment during their time working in State government. At the urging of these brave women and other tireless advocates, the goal of the hearing was to gather information that would reveal opportunities to create stronger and clearer policies and procedures that will endure in public and private sectors throughout the state. Legislative leaders hoped that the hearing might aid in the strengthening of proposed legislation and spur the development of new legislation that will make New York State a leader in workplace safety and anti-harassment law. -

General Election Snapshot Election General City on Tuesday, Races That Will Take Lists General Election Section This in New York Place in Their Races

General Election Snapshot STATEWIDE OFFICES CIVIL COURT JUDGES Governor Term of Office: 10 YEARS (no term limit) Term of Office: 4 YEARS (no term limit) Salary: $193,500 This section lists General Election races that will take place in New York City on Tuesday, Salary: $179,000 November 6th, including candidates who are unopposed in their races. County – New York All statewide offices – Governor, Attorney General, and Comptroller – will be on the ballot Lieutenant Governor Term of Office: 4 YEARS (no term limit) Vote for 2 this year. There are also elections for all New York State Senate and Assembly seats, as Salary: $151,500 Shahabuddeen A. Ally (D) well as for judicial positions and federal offices. Three proposals from the New York City Ariel D. Chesler (D) Charter Revision Commission will also be on the ballot (see page 5 for Citizens Union’s Andrew M. Cuomo & Kathy C. Hochul positions on the referenda). (D, I, WE, WF) † ^ District – 1st Municipal Court – Howie Hawkins & Jia Lee (G)^ New York † Incumbent Stephanie A. Miner & Michael J. Volpe Frank P. Nervo (D) ^ Denotes that the candidate submitted the Citizens Union questionnaire. Responses (SAM)^ from Gubernatorial candidates and state Senate and Assembly candidates can be Marc Molinaro & Julie Killian (R, C, REF)^ District - 2nd Municipal Court – found on pages 10-13. Questionnaire responses for Attorney General and Comptroller Larry Sharpe & Andrew C. Hollister (L)^ New York candidates can be found at www.CitizensUnion.org. Wendy C. Li (D) Bold denotes the candidate is endorsed by Citizens Union in the general election. New York State * Denotes that the district overlaps boroughs. -

In Response to the Confirmation of Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court, a Coalition of Elected Officials in New York City Released the Following Statement

In response to the confirmation of Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court, a coalition of elected officials in New York City released the following statement: “Ostensibly, the role of the Supreme Court is not to make policy, or to implement a political agenda. It’s to determine whether or not the policies and the political agendas enacted by other branches of government are consistent with the Constitution and the laws of the United States. But this narrative simply isn’t true. The Supreme Court has always been a political institution. The Republican Party recognizes this reality and uses aggressive tactics to stack the courts with right-wing ideologues, cultivated in their own parallel legal ecosystem. Meanwhile, the Democratic Party has fought to preserve the myth of our apolitical judiciary, unilaterally disarming in the battles that decide which judges are confirmed to the federal bench. This asymmetry is exacerbated by our dysfunctional electoral system. Hundreds of federal judges - including a majority on the Supreme Court - have now been appointed by presidents who lost the popular vote. The result has been catastrophic. A right-wing supermajority now sits on the Supreme Court. The federal judiciary is teeming with hundreds of conservative fanatics appointed by Donald Trump. They are poised to destroy what little remains of abortion access, labor rights, civil rights protections, and social insurance. Not only do these extremist judges threaten more than a century of progressive achievements, they threaten to foreclose the possibility of any future progress under a Democratic administration. Already, the Roberts court has gutted the most progressive elements of the Affordable Care Act, denying Medicaid coverage to millions of poor Americans. -

Budget Equity Xxviii 2020 Vision: an Anti-Poverty Agenda

NEW YORK STATE BLACK, PUERTO RICAN, HISPANIC, AND ASIAN LEGISLATIVE CAUCUS Assemblywoman Tremaine Wright, Chairperson THE PEOPLE’S BUDGET BUDGET EQUITY XXVIII 2020 VISION: AN ANTI-POVERTY AGENDA Assemblywoman Senator Assemblyman Senator Assemblywoman Yuh-Line Niou Jamaal Bailey Félix Ortiz Jessica Ramos Nathalia Fernandez Caucus Budget Co-Chair Caucus Budget Co-Chair Caucus Budget Co-Chair Caucus Budget Co-Chair Caucus Budget Co-Chair OFFICERS Assemblywoman Tremaine Wright, Chairperson Assemblywoman Michaelle Solages, 1st Vice Chairperson Senator Luis Sepulveda, 2nd Vice Chairperson Assemblyman Victor Pichardo, Secretary Senator Brian A. Benjamin, Treasurer Assemblywoman Yuh-Line Niou, Parliamentarian Assemblywoman Latrice M. Walker, Chaplain MEMBERS OF THE ASSEMBLY Carmen E. Arroyo Kimberly Jean-Pierre Jeffrion L. Aubry Latoya Joyner Charles Barron Ron Kim Rodneyse Bichotte Walter Mosley Michael A. Blake Felix Ortiz Vivian E. Cook Crystal D. Peoples-Stokes Marcos Crespo N. Nick Perry Catalina Cruz J. Gary Pretlow Taylor Darling Philip Ramos Maritza Davila Karines Reyes Carmen De La Rosa Diana C. Richardson Inez E. Dickens Jose Rivera Erik M. Dilan Robert J. Rodriguez Charles D. Fall Nily Rozic Nathalia Fernandez Nader Sayegh Mathylde Frontus Al Taylor David F. Gantt Clyde Vanel Pamela J. Hunter Jaime Williams Alicia L. Hyndman SPEAKER OF THE ASSEMBLY Carl E. Heastie MEMBERS OF THE SENATE Jamaal Bailey Kevin S. Parker Leroy Comrie Roxanne Persaud Robert Jackson Jessica Ramos Anna Kaplan Gustavo Rivera John Liu Julia Salazar Monica R. -

The { 2 0 2 1 N Y C } »G U I D E«

THE EARLY VOTING STARTS JUNE 12 — ELECTION DAY JUNE 22 INDYPENDENT #264: JUNE 2021 { 2021 NYC } ELECTION » GUIDE« THE MAYOR’S RACE IS A HOT MESS, BUT THE LEFT CAN STILL WIN BIG IN OTHER DOWNBALLOT RACES {P8–15} LEIA DORAN LEIA 2 EVENT CALENDAR THE INDYPENDENT THE INDYPENDENT, INC. 388 Atlantic Avenue, 2nd Floor Brooklyn, NY 11217 212-904-1282 www.indypendent.org Twitter: @TheIndypendent facebook.com/TheIndypendent SUE BRISK BOARD OF DIRECTORS Ellen Davidson, Anna Gold, Alina Mogilyanskaya, Ann tions of films that and call-in Instructions, or BRYANT PARK SPIRIT OF STONEWALL: The Schneider, John Tarleton include political, questions. RSVP by June 14. 41 W. 40th St., third annual Queer Liberation March will be pathbreaking and VIRTUAL Manhattan held Sunday June 27. EDITOR-IN-CHIEF JUNE visually inspir- John Tarleton ing selections. JUNE 18–20 ONGOING JUNE 4–20 The theater will JUNETEENTH NY FESTIVAL • 8AM–5PM • FREE Lincoln Center is opening a CONTRIBUTING EDITORS TIME & PRICE (EST. $50) TBD. continue to offer virtual FREE OUTDOORS: SHIRLEY CH- giant outdoor performing Ellen Davidson, Alina POP UP MAGAZINE: THE SIDE- cinema for those that don’t yet Juneteenth NYC’s 12th ISHOLM STATE PARK arts center that will include Mogilyanskaya, Nicholas WALK ISSUE feel comfortable going to the annual celebration starts on Named in honor of a Brooklyn- 10 different performance and Powers, Steven Wishnia This spring, the multimedia movies in person. Friday with professionals and born trailblazer who was the rehearsal spaces. Audience storytelling company Pop-Up BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF residents talking about Health fi rst Black congresswoman, members can expect free and ILLUSTRATION DIRECTOR Magazine takes to the streets. -

New York State Senate Higher Education Committee Hearing On

New York State Senate Higher Education Committee Hearing on the Cost of Public Education Submitted by Melanie Kruvelis, Senior Manager of Policy and Advocacy, Young Invincibles October 24, 2019 Good morning. My name is Melanie Kruvelis, and I am the Senior Manager of Policy and Advocacy at Young Invincibles. Young Invincibles is a policy and advocacy non-profit dedicated to elevating young adults in the political process and expanding economic opportunities for our generation. We work with young adults across the country and in our five state offices (New York, Texas, California, Illinois, and Colorado) to ensure that our voices are at the table when it comes to higher education, health care, workforce development, and civic engagement. I want to thank Senator Toby Ann Stavisky for bringing folks together for this important hearing on the cost of public education in New York State, and her leadership on the Senate Higher Education Committee. I also want to thank Senators Andrew Gounardes, Kevin Parker, Julia Salazar, and Velmanette Montgomery for their commitment to college access and success in New York City. Today’s hearing comes at a critical moment for New York’s college students. Today, nine out of every ten jobs created in the United States go to those with a college degree.1 In New York City, workers with a bachelor’s degree earn, on average, $550 more per week than those with a high school diploma.2 While there are multiple pathways to a living-wage career, a college degree remains one of the best bets a person can make to attaining long-term economic stability. -

Public Protection 2021 Transcript

1 1 BEFORE THE NEW YORK STATE SENATE FINANCE AND ASSEMBLY WAYS AND MEANS COMMITTEES 2 ----------------------------------------------------- 3 JOINT LEGISLATIVE HEARING 4 In the Matter of the 2021-2022 EXECUTIVE BUDGET ON 5 PUBLIC PROTECTION 6 ----------------------------------------------------- 7 Virtual Hearing Held via Zoom 8 February 10, 2021 9 9:40 a.m. 10 PRESIDING: 11 Senator Liz Krueger 12 Chair, Senate Finance Committee 13 Assemblywoman Helene E. Weinstein Chair, Assembly Ways & Means Committee 14 PRESENT: 15 Senator Thomas F. O'Mara 16 Senate Finance Committee (RM) 17 Assemblyman Edward P. Ra Assembly Ways & Means Committee (RM) 18 Senator Brad Hoylman 19 Chair, Senate Committee on Judiciary 20 Assemblyman Charles D. Lavine Chair, Assembly Committee on Judiciary 21 Senator Jamaal T. Bailey 22 Chair, Senate Committee on Codes 23 Assemblyman Jeffrey Dinowitz Chair, Assembly Committee on Codes 24 2 1 2021-2022 Executive Budget Public Protection 2 2-10-21 3 PRESENT: (Continued) 4 Senator Julia Salazar Chair, Senate Committee on Crime Victims, 5 Crime and Correction 6 Assemblyman David I. Weprin Chair, Assembly Committee on Correction 7 Senator John E. Brooks 8 Chair, Senate Committee on Veterans, Homeland Security and Military Affairs 9 Assemblyman Kenneth P. Zebrowski 10 Chair, Assembly Committee on Governmental Operations 11 Senator Diane J. Savino 12 Chair, Senate Committee on Internet and Technology 13 Senator Gustavo Rivera 14 Assemblyman Harry B. Bronson 15 Senator Pete Harckham 16 Assemblyman Edward C. Braunstein 17 Assemblywoman Deborah J. Glick 18 Senator Andrew Gounardes 19 Assemblyman Erik M. Dilan 20 Assemblywoman Jenifer Rajkumar 21 Assemblyman Phil Steck 22 Assemblywoman Dr. Anna R. -

Why I Voted Against Endorsing Cynthia Nixon

Why I Voted Against Endorsing Cynthia Nixon The leadership of the New York City chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) voted this past weekend by a two- thirds majority to endorse Cynthia Nixon in the Democratic Primary race for New York State governor. The decision reflected similar majorities for Nixon among the total membership of the New York City branches. An accompanying motion also passed that linked DSA’s work on the Nixon campaign to the Julia Salazar campaign in the Democratic Primary for State Senate and tied it to our organization’s support for the New York State Health Act and the a city campaign create for expanded rent stabilization. Since the majority of my fellow New York City socialists voted to endorse Nixon, I feel obligated as a member of the City Leadership Committee (CLC) to explain to our members why I cast my vote against, as did eleven other members of the 34- member body, while one person abstained. I will try in this brief statement to make clear first what seemed to me to be the principle reasons given to support or reject the endorsement and why i took the position that i did. Let me begin, however, by stating that some at the meeting argued that since the majority of our members had voted to endorse Nixon, that we were all obligated to vote to endorse her. I disagreed because as I stated at the meeting, I was elected in my Central Brooklyn branch by members who know that, while generally supportive of our electoral work over the past three years, I am dubious about the “Progressive” Democrats and about strategies that tend to suggest that we can have significant influence in the Democratic Party or on its candidates. -

Cynthia Nixon Vs Andrew Cuomo: Sex Or No Sex in the City” Published on Iitaly.Org (

Cynthia Nixon vs Andrew Cuomo: Sex or No Sex in the City” Published on iItaly.org (http://ftp.iitaly.org) Cynthia Nixon vs Andrew Cuomo: Sex or No Sex in the City” Jerry Krase (September 24, 2018) The tallies are in for the Democratic Party primary race for New York State Governor, and unfortunately for most of us self-identified libidinous “Progressives” the answer is “NO.” Although allegedly “left-leaning” candidates, especially those of the female-kind, knocked off some “right- leaning” lower level, nominally Democratic Party incumbents, Governor Andrew Cuomo was the last man standing at the top. Well the tallies are in for the Democratic Party primary race for New York State Governor, and unfortunately for most of us self-identified libidinous “Progressives” the answer is “NO.” Although allegedly “left-leaning” candidates, especially those of the female-kind, knocked off some “right- leaning” lower level, nominally Democratic Party incumbents, Governor Andrew Cuomo was the last man standing at the top. A few pandering pundits have offered that this “trouncing” of Sex in the Citycelebrity Cynthia Nixon well-positions him for a run at the U.S. Presidency, but speculation about Multi-Billionaire Michael Bloomberg’s entrance in the race might make him one New Yorker too many. Page 1 of 3 Cynthia Nixon vs Andrew Cuomo: Sex or No Sex in the City” Published on iItaly.org (http://ftp.iitaly.org) One of my favorite New York Times writers on the city, Ginia Bellafante, for the most part, agrees with my own assessment as to why the fast start slowed to a halt when she ran up against the real politikpracticed by the current tenant of the Governor’s mansion. -

NPC Senate and Assembly District

Neighborhood Preservation Company List 2020 SD Senator AD Assembly Member Housing Help, Inc. SD2 Mario Mattera AD10 Steve Stern SD5 James Gaughran AD12 Keith Brown Regional Economic Community Action Program, Inc. (RECAP) SD42 Mike Martucci AD100 Aileen Gunther Utica Neighborhood Housing Services, Inc. SD47 Joseph Griffo AD101 Brian Miller AD119 Marianne Buttenschon PathStone Community Improvement of Newburgh, Inc. SD39 James Skoufis AD104 Jonathan Jacobson Hudson River Housing, Inc. SD41 Susan Serino AD104 Jonathan Jacobson TAP, Inc. SD44 Neil Breslin AD107 Jacob Ashby AD108 John McDonald South End Improvement Corp. SD44 Neil Breslin AD108 John McDonald TRIP, Inc. SD44 Neil Breslin AD108 John McDonald Albany Housing Coalition, Inc. SD44 Neil Breslin AD108 John McDonald AD109 Pat Fahy Arbor Hill Development Corp. SD44 Neil Breslin AD108 John McDonald AD109 Pat Fahy United Tenants of Albany, Inc. SD44 Neil Breslin AD108 John McDonald AD109 Pat Fahy Better Community Neighborhoods, Inc. SD49 James Tedisco AD110 Phil Steck AD111 Angelo Santabarbara Shelters of Saratoga, Inc. SD43 Daphne Jordan AD113 Carrie Woerner Neighbors of Watertown, Inc. SD48 Patricia Ritchie AD116 Mark Walczyk First Ward Action Council, Inc. SD52 Fred Akshar AD123 Donna Lupardo Metro Interfaith Housing Management Corp. SD52 Fred Akshar AD123 Donna Lupardo Near Westside Neighborhood Association, Inc. SD58 Thomas O'Mara AD124 Christopher Friend Ithaca Neighborhood Housing Services, Inc. SD51 Peter Oberacker AD125 Anna Kelles SD58 Thomas O'Mara Homsite Fund, Inc. SD50 John Mannion AD126 John Lemondes Jr. SD53 Rachel May AD128 Pamela Hunter Syracuse United Neighbors, Inc. AD129 William Magnarelli Housing Visions Unlimited, Inc. SD53 Rachel May AD128 Pamela Hunter AD129 William Magnarelli NEHDA, Inc.