3 Orozco, Rivera, Siqueiros Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

David Alfaro Siqueiros Papers, 1921-1991, Bulk 1930-1936

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf9t1nb3n3 No online items Finding aid for the David Alfaro Siqueiros papers, 1921-1991, bulk 1930-1936 Annette Leddy Finding aid for the David Alfaro 960094 1 Siqueiros papers, 1921-1991, bulk 1930-1936 Descriptive Summary Title: David Alfaro Siqueiros papers Date (inclusive): 1920-1991 (bulk 1930-1936) Number: 960094 Creator/Collector: Siqueiros, David Alfaro Physical Description: 2.11 Linear Feet(6 boxes) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: A leading member of the Mexican muralist movement and a technical innovator of fresco and wall painting. The collection consists almost entirely of manuscripts, some in many drafts, others fragmentary, the bulk of which date from the mid-1930s, when Siqueiros traveled to Los Angeles, New York, Buenos Aires, and Montevideo, returning intermittently to Mexico City. A significant portion of the papers concerns Siqueiros's public disputes with Diego Rivera; there are manifestos against Rivera, eye-witness accounts of their public debate, and newspaper coverage of the controversy. There is also material regarding the murals América Tropical, Mexico Actual and Ejercicio Plastico, including one drawing and a few photographs. The Experimental Workshop in New York City is also documented. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in Spanish; Castilian and English Biographical/Historical Note David Alfaro Siqueiros was a leading member of the Mexican muralist movement and a technical innovator of fresco and wall painting. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Re-Conceptualizing Social Medicine in Diego Rivera's History of Medicine in Mexico: The People's Demand for Better Health Mural, Mexico City, 1953. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7038q9mk Author Gomez, Gabriela Rodriguez Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Re-Conceptualizing Social Medicine in Diego Rivera's History of Medicine in Mexico: The People's Demand for Better Health Mural, Mexico City, 1953. A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History by Gabriela Rodriguez-Gomez June 2012 Thesis Committee: Dr. Jason Weems, Chairperson Dr. Liz Kotz Dr. Karl Taube Copyright by Gabriela Rodriguez-Gomez 2012 The Thesis of Gabriela Rodriguez-Gomez is approved: ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California Riverside Acknowledgements I dedicate my thesis research to all who influenced both its early and later developments. Travel opportunities for further research were made possible by The Graduate Division at UC Riverside, The University of California Humanities Research Institute, and the Rupert Costo Fellowship for Native American Scholarship. I express my humble gratitude to my thesis committee, Art History Professors Jason Weems (Chair), Liz Kotz, and Professor of Anthropology Karl Taube. The knowledge, insight, and guidance you all have given me throughout my research has been memorable. A special thanks (un agradecimiento inmenso) to; Tony Gomez III, Mama, Papa, Ramz, The UCR Department of Art History, Professor of Native North American History Cliff Trafzer, El Instituto Seguro Social de Mexico (IMSS) - Sala de Prensa Directora Patricia Serrano Cabadas, Coordinadora Gloria Bermudez Espinosa, Coordinador de Educación Dr. -

ARTH 599 Mexican Muralism

MEXICAN MURALISM (ARTH 472 002/599 003) Class time: Wednesday 4:30-7:10 Location: Research 1 201 Professor: Michele Greet Email: [email protected] Phone: (703) 993-3479 Office: Robinson Hall B 371A Office Hours: Wednesday 3:00-4:00 or by appointment (please email me to let me know you will be coming, or to schedule a meeting for a different time) Course Description: Mexican muralism emerged as a means for artists to promote the social ideals of the Revolution (1911-1920). Backed by political and cultural leaders, Mexican artists sought to build a new national consciousness by celebrating the culture and heritage of the Mexican people. This public monumental art also created a forum for the education of the populace about the living conditions of the peasantry. Despite the utopian objectives of the project, however, conflict emerged among the muralists and their sponsors as to how this vision should be achieved. This course will address the various aims and ideologies of the Mexican muralists and muralism’s impact in the United States. *This course includes a required embedded study abroad component in Mexico City over the spring break Course Format: This class will consist of seminar-style discussions of assigned readings. In the first half of each class I will lecture on the topic assigned for that week. The second half of class will consist of critical assessment of the readings led by different students in the class. Written assignments will complement in-class discussions. Writing Intensive requirement: This course fulfills all/in part the Writing Intensive requirement in the Art History major. -

Mexican Murals and Fascist Frescoes

Mexican Murals and Fascist Frescoes: Cultural Reinvention in 20th-Century Mexico and Italy An honors thesis for the Department of International Literary and Visual Studies Maya Sussman Tufts University, 2013 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Professor Adriana Zavala for her encouragement, guidance, and patience throughout each step of this research project. I am grateful to Professor Laura Baffoni-Licata and Professor Silvia Bottinelli for both supporting me and challenging me with their insightful feedback. I also wish to acknowledge Kaeli Deane at Mary-Anne Martin/Fine Art for inviting me to view Rivera’s Italian sketchbook, and Dean Carmen Lowe for her assistance in funding my trip to New York through the Undergraduate Research Fund. Additionally, I am grateful to the Academic Resource Center for providing supportive and informative workshops for thesis writers. Finally, I want to thank my friends and family for supporting me throughout this project and the rest of my time at Tufts. Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Diego Rivera’s Sketches from Italy: The Influence of Italian Renaissance Art on the Murals at the Ministry of Public Education and Chapingo Chapel ................................................ 7 Chapter 2: Historical Revival in Fascist Italy: Achille Funi’s Mito di Ferrara Frescoes........... 46 Chapter 3: Muralists’ Manifestos and the Writing of Diego Rivera and Achille Funi .............. -

Translating Revolution: U.S

A Spiritual Manifestation of Mexican Muralism Works by Jean Charlot and Alfredo Ramos Martínez BY AMY GALPIN M.A., San Diego State University, 2001 B.A., Texas Christian University, 1999 THESIS Submitted as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Chicago, 2012 Chicago, Illinois Defense Committee: Hannah Higgins, Chair and Advisor David M. Sokol Javier Villa-Flores, Latin American and Latino Studies Cristián Roa-de-la-Carrera, Latin American and Latino Studies Bram Dijkstra, University of California San Diego I dedicate this project to my parents, Rosemary and Cas Galpin. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My committee deserves many thanks. I would like to recognize Dr. Hannah Higgins, who took my project on late in the process, and with myriad commitments of her own. I will always be grateful that she was willing to work with me. Dr. David Sokol spent countless hours reading my writing. With great humor and insight, he pushed me to think about new perspectives on this topic. I treasure David’s tremendous generosity and his wonderful ability to be a strong mentor. I have known Dr. Javier Villa-Flores and Dr. Cristián Roa-de-la-Carrera for many years, and I cherish the knowledge they have shared with me about the history of Mexico and theory. The independent studies I took with them were some of the best experiences I had at the University of Illinois-Chicago. I admire their strong scholarship and the endurance they had to remain on my committee. -

Mexican Muralism: Los Tres Grandes David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco

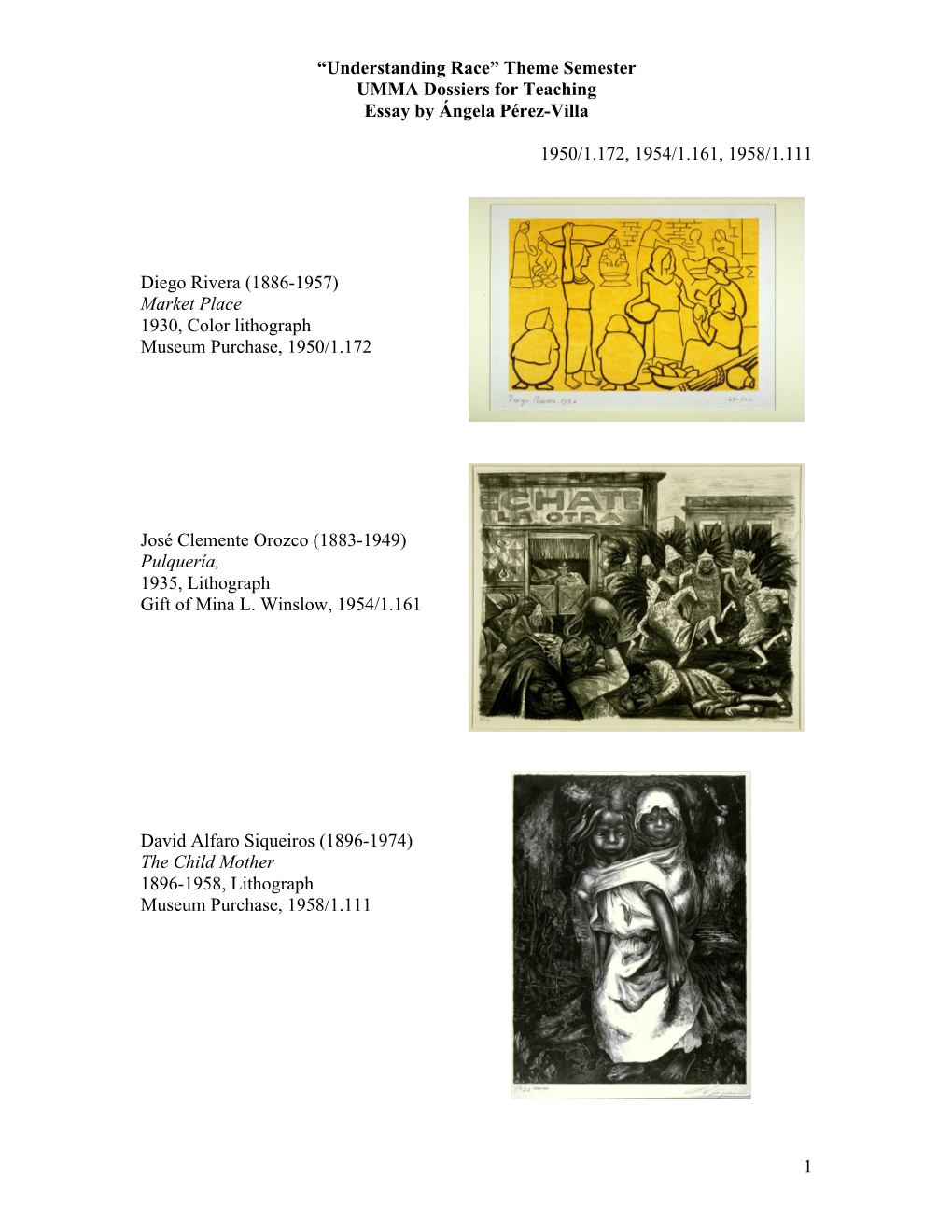

Mexican Muralism: Los Tres Grandes David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco David Alfaro Siqueiros, Mexican History or the Right for Culture, National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), 1952-56, (Mexico City, hoto: Fausto Puga) Siqueiros and Mexican History At the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) in Mexico City visitors enter the rectory (the main administration building), beneath an imposing three-dimensional arm emerging from a mural. Several hands, one with a pencil, charge towards a book, which lists critical dates in Mexico’s history: 1520 (the Conquest by Spain); 1810 (Independence from Spain); 1857 (the Liberal Constitution which established individual rights); and 1910 (the start of the Revolution against the regime of Porfirio Díaz). David Alfaro Siqueiros left the final date blank in Dates in Mexican History or the Right for Culture (1952-56), inspiring viewers to create Mexico’s next great historic moment. The Revolution From 1910 to 1920 civil war ravaged the nation as citizens revolted against dictator Porfirio Díaz. At the heart of the Revolution was the belief—itself revolutionary—that the land should be in the hands of laborers, the very people who worked it. This demand for agrarian reform signaled a new age in Mexican society: issues concerning the popular masses—universal public education and health care, expanded civil liberties—were at the forefront of government policy. Mexican Muralism At the end of the Revolution the government commissioned artists to create art that could educate the mostly illiterate masses about Mexican history. Celebrating the Mexican people’s potential to craft the nation’s history was a key theme in Mexican muralism, a movement led by Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco—known as Los tres grandes. -

The Mexican and Chicano Mural Movements

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 2006 Volume II: Latino Cultures and Communities The Mexican and Chicano Mural Movements Curriculum Unit 06.02.01 by María Cardalliaguet Gómez-Málaga As an educator and as a language teacher, my priority is to inculcate a global consciousness and an international perspective based in respect to all my students. I consider it crucial to teach them to value how lucky they are to grow up in a multi-cultural society. Most of the high school students I teach are not aware of the innumerable personal and educational advantages this society/environment provides them. As a Spanish teacher, I try to do this through the study of identity, society and culture of the many countries that form what has been called the Hispanic/Latino World. I have always in mind the "5Cs"- Cultures, Connections (among disciplines), Comparisons (between cultures), Communication, and Communities- that the National Standards of Foreign Language Learning promote, and I intend to put them into context in this unit. The present unit offers me the opportunity to introduce art in the classroom in a meaningful way and as an instrument to teach history, culture and language. Some of my students have not yet been exposed to different artistic movements, and they find it difficult to interpret what they see. In this unit, students will learn about the renaissance of public mural painting in Mexico after the Revolution (1910-1917) and about Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros, the three leading Mexican muralists, who turned revolutionary propaganda into one of the most powerful and significant achievements in the 20th century art. -

An Investigation of Urban Artists’ Mobilizing Power in Oaxaca and Mexico City

THE UNOFFICIAL STORY AND THE PEOPLE WHO PAINT IT: AN INVESTIGATION OF URBAN ARTISTS’ MOBILIZING POWER IN OAXACA AND MEXICO CITY by KENDRA SIEBERT A THESIS Presented to the Department of Journalism and Communication and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2019 An Abstract of the Thesis of Kendra Siebert for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of Journalism and Communication to be taken June 2019 Title: The Unofficial Story and the People Who Paint It: An Investigation of Urban Artists’ Mobilizing Power in Oaxaca and Mexico City Approved: _______________________________________ Peter Laufer Although parietal writing – the act of writing on walls – has existed for thousands of years, its contemporary archetype, urban art, emerged much more recently. An umbrella term for the many kinds of art that occupy public spaces, urban art can be accessed by whoever chooses to look at it, and has roots in the Mexican muralism movement that began in Mexico City and spread to other states like Oaxaca. After the end of the military phase of the Mexican Revolution in the 1920s, philosopher, writer and politician José Vasconcelos was appointed to the head of the Mexican Secretariat of Public Education. There, he found himself leading what he perceived to be a disconnected nation, and believed visual arts would be the means through which to unify it. In 1921, Vasconcelos proposed the implementation of a government-funded mural program with the intent of celebrating Mexico and the diverse identities that comprised it. -

Colombia in the 1930S - the Case of Ignacio Gómez Jaramillo Revista Historia Y MEMORIA, Núm

Revista Historia Y MEMORIA ISSN: 2027-5137 [email protected] Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia Colombia Solano Roa, Juanita The Mexican Assimilation: Colombia in the 1930s - The case of Ignacio Gómez Jaramillo Revista Historia Y MEMORIA, núm. 7, 2013, pp. 79-111 Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=325129208004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative The Mexican Assimilation: Colombia in the 1930s - The case of Ignacio Gómez Jaramillo Juanita Solano Roa1 Institute of Fine Arts, New York-Estados Unidos Recepción: 09/09/2013 Evaluación: 09/09/2013 Aceptación: 05/10/2013 Artículo de Investigación Científica. Abstract During the 1930s in Colombia, artists such as Ignacio Gómez Jaramillo, took Mexican muralism as an important part of their careers thus engaging with public art for the first time in the country. In 1936, Gómez Jaramillo travelled to Mexico for two years in order to study muralism, to learn the fresco technique and to transmit the Mexican experience of the open-air-schools. Gómez Jaramillo returned to Colombia in 1938 and in 1939 painted the murals of the National Capitol. Although Gómez Jaramillo’s work after 1939 is well known, his time in Mexico has been barely studied and very few scholars have analyzed the artist’s work in light of his Mexican experience. While in Mexico, Gómez Jaramillo joined the LEAR (La Liga de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios) with whom he crated the murals of the Centro Escolar 1 Licenciada en Artes, Universidad de los Andes-Colombia. -

Mexican Muralism: an Expression of Identity and History

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Trinity Publications (Newspapers, Yearbooks, The First-Year Papers (2010 - present) Catalogs, etc.) 2020 Mexican Muralism: An Expression of Identity and History Andrew Briden Trinity College, Hartford Connecticut Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/fypapers Recommended Citation Briden, Andrew, "Mexican Muralism: An Expression of Identity and History". The First-Year Papers (2010 - present) (2020). Trinity College Digital Repository, Hartford, CT. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/fypapers/98 2020 Mexican Muralism: An Expression of Identity and History Andrew Briden Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut Mexican Muralism: An Expression of Identity and History 1 Mexican Muralism: An Expression of Identity and History Andrew Briden The Mexican muralist Diego Rivera believed that art was for everyone. In a country like Mexico, where old colonial structures pervaded social class and wealth, the people looked to revolution as the answer. During the decade long Mexican Revolution of 1910, and after it, Mexican Muralism revealed itself to be an art style for the masses, a vehicle in which to discover what it truly meant to be Mexican. Mexican Muralism in the 1930’s, led by Diego Rivera, was an integral shift to an exploration of a more political interpretation of Mexico's history and the implications that it had on national identity. The origins of Mexican Muralism began with commissions from José Vasconcelos, the minister of education under Álvaro Obregon’s presidency from 1920 to 1924. Vasconcelos commissioned murals from leading Mexican artists like Diego Rivera, Jose Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. His idea was that murals would educate the larger public, who at the time were largely illiterate. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO Reimagining

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO Reimagining the Mexican Revolution in the United Farm Workers’ El Malcriado (1965-1966) A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Art History, Theory, and Criticism by Julia Fernandez Committee in charge: Professor Mariana Razo Wardwell, Chair Professor William Norman Bryson Professor Grant Kester Professor Shelley Streeby 2018 Copyright Julia Fernandez, 2018 All Rights Reserved. This Thesis of Julia Fernandez is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California San Diego 2018 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page..................................................................................................................iii Table of Contents.............................................................................................................iv List of Figures...................................................................................................................v Abstract of the Thesis......................................................................................................vi Introduction.......................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Mexico’s Taller de Gráfica Popular in El Malcriado......................................5 Chapter 2 “Sons of the Mexican Revolution”................................................................18 Chapter 3 Don Sotaco, Don -

The Mexican Muralist Movement and an Exploration of Public Art

The Mexican oject Muralist Movement and an Exploration of Public Art Denver Public Schools In partnership with Metropolitan State College of Denver Alma de la Raza Pr El The Mexican Muralist Movement and an Exploration of Public Art By Jennifer Henry Grades 10–12 Implementation Time for Unit of Study: 3–4 weeks Denver Public Schools El Alma de la Raza Curriculum and Teacher Training Program Loyola A. Martinez, Project Director Dan Villescas, Curriculum Development Specialist El Alma de la Raza Series El The Mexican Muralist Movement and an Exploration of Public Art The Mexican Muralist Movement and an Exploration of Public Art Unit Concepts • History’s influence on artistic and cultural movements and developments. • Visual arts as an effective form of communication. • The political and social issues presented in or reflected by Mexican muralism. • Public art, including contemporary murals and graffiti, and its social and political influences. • The ability of art to influence the public, rewrite history, make social commentary, and provide spiritual and cultural ideals. Standards Addressed by This Unit Visual Arts Students recognize and use the visual arts as a form of creativity and communication. (VA1) Students know and apply elements of art, principles of design, and sensory, expressive, and creative features of visual arts. (VA2) Students know and apply visual arts materials, tools, techniques, and processes. (VA3) Students relate the visual arts to various historical and cultural traditions. (VA4) Students analyze and evaluate the characteristics, merits, and meaning of works of art. (VA5) History Students understand the chronological organization of history and know how to organize events and people into major eras to identify and explain historical relationships.