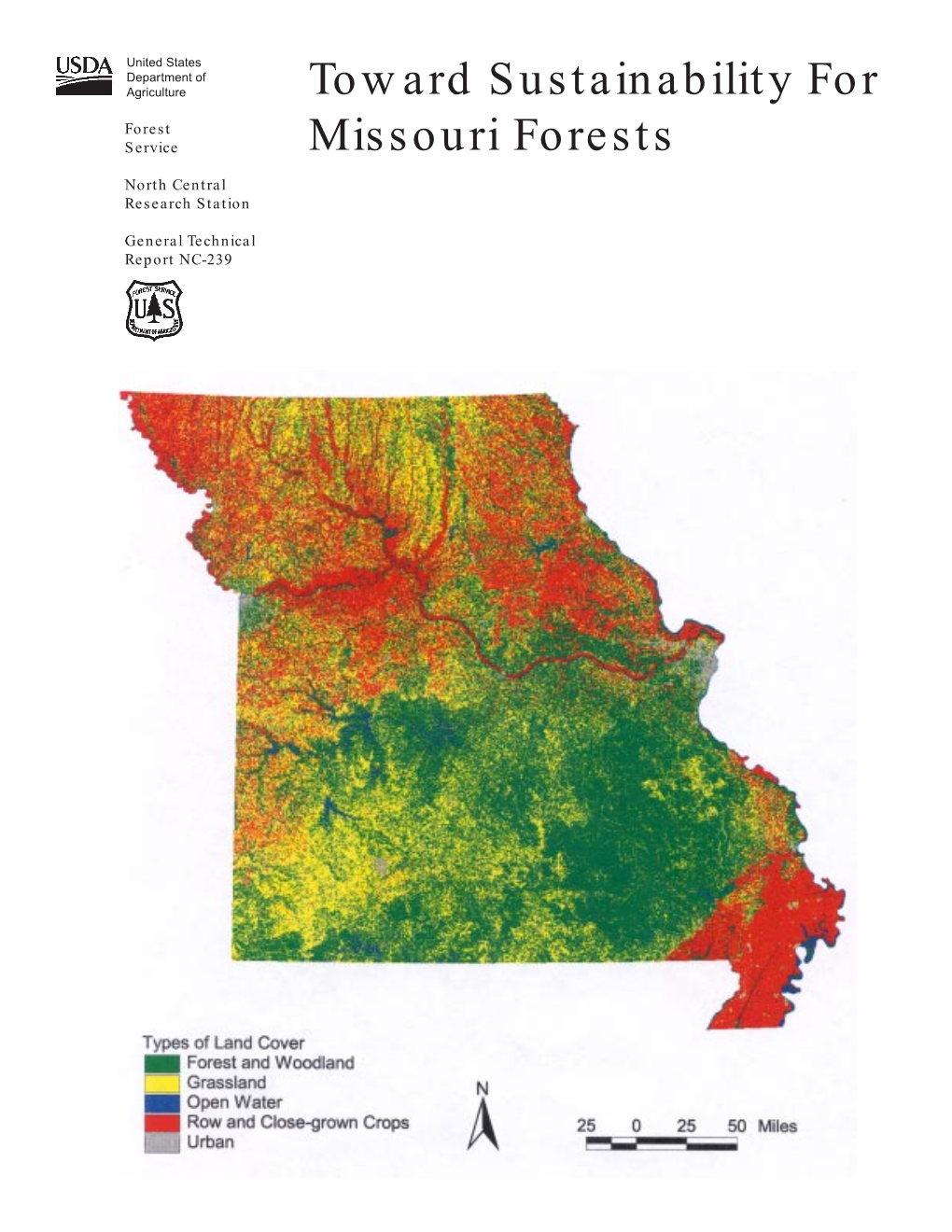

Toward Sustainability for Missouri Forests Susan L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Summer 2019

ALABAMA’S REASURED T FORESTS A Publication of the Alabama Forestry Commission Spring/Summer 2019 Message from the GOVERNOR STATE FORESTER Kay Ivey ALABAMA FORESTRY COMMISSION n my letter for this magazine, I want to take a different Katrenia Kier, Chairman approach than I normally do. A little-known responsibili- Robert N. Turner, Vice Chair ty of the Alabama Forestry Commission is helping the Robert P. Sharp state in times of disaster. Sure, when a tornado, hurricane, Stephen W. May III Ior ice storm hits, we are on the scene with chainsaws and Jane T. Russell equipment to clear the roads, but we offer much more than Dr. Bill Sudduth Joseph Twardy that. Through our training to fight wildfires, we have an inci- dent management team ready at all times to serve the state. I STATE FORESTER want to take this opportunity to brag on the men and women Rick Oates who make up this team and agency. As everyone knows, on March 3rd a series of tornadoes Rick Oates, State Forester ASSISTANT STATE FORESTER devastated parts of Lee County. Twenty-three people were Bruce Springer killed, and the homes of many more were destroyed. It was total devastation in parts of the county. As is often the case, the Alabama Forestry Commission was FOREST MANAGEMENT DIVISION DIRECTOR called in to assist the citizens of Lee County. Through this effort, my eyes were Will Brantley opened to the true capabilities of the Alabama Forestry Commission. PROTECTION DIVISION DIRECTOR Our team, led by James “Moto” Williams, jumped into action and took over John Goff the coordination of volunteers; at first in Smiths Station, and later in Beauregard. -

Health Guidelines Vegetation Fire Events

HEALTH GUIDELINES FOR VEGETATION FIRE EVENTS Background papers Edited by Kee-Tai Goh Dietrich Schwela Johann G. Goldammer Orman Simpson © World Health Organization, 1999 CONTENTS Preface and acknowledgements Early warning systems for the prediction of an appropriate response to wildfires and related environmental hazards by J.G. Goldammer Smoke from wildland fires, by D E Ward Analytical methods for monitoring smokes and aerosols from forest fires: Review, summary and interpretation of use of data by health agencies in emergency response planning, by W B Grant The role of the atmosphere in fire occurrence and the dispersion of fire products, by M Garstang Forest fire emissions dispersion modelling for emergency response planning: determination of critical model inputs and processes, by N J Tapper and G D Hess Approaches to monitoring of air pollutants and evaluation of health impacts produced by biomass burning, by J P Pinto and L D Grant Health impacts of biomass air pollution, by M Brauer A review of factors affecting the human health impacts of air pollutants from forest fires, by J Malilay Guidance on methodology for assessment of forest fire induced health effects, by D M Mannino Gaseous and particulate emissions released to the atmosphere from vegetation fires, by J S Levine Basic fact-determining downwind exposures and their associated health effects, assessment of health effects in practice: a case study in the 1997 forest fires in Indonesia, by O Kunii Smoke episodes and assessment of health impacts related to haze from forest -

Social Sustainability: a Comparison of Case Studies in UK, USA and Australia

17th Pacific Rim Real Estate Society Conference, Gold Coast, 16-19 Jan 2011 Social Sustainability: A Comparison of Case Studies in UK, USA and Australia Michael Y MAK and Clinton J PEACOCK School of Architecture and Built Environment The University of Newcastle, Australia Abstract Traditionally, the sustainable development concept emphasizes on environmental areas such as waste and recycling, energy efficiency, water resource, building design, carbon emission, and aims to eliminate negative environmental impact while continuing to be completely ecologically sustainable through skilful and sensitive design. However, contemporarily sustainable development also implies an improvement in the quality of life through education, justice, community participation, and recreation. Recently social sustainability has gained an increased awareness as a fundamental component of sustainable development to encompass human rights, labour rights, and corporate governance. The goals of social sustainability are that future generations should have the same or greater access to social resources as the current generation. This paper aims to reveal the level of focus a development has in meeting social sustainable goals, success factors for a development, and planning a development now and into the future from a socially orientated perspective. This paper examines the characteristics of social sustainable developments through the comparison of three case studies: the Thames Gateway in east of London, UK, the Sonoma Mountain Village in north of San Francisco, -

Summary of the Report : Onboard Employment Socio-Economic Impact of a Sustainable Fisheries Model

Summary of the report : Onboard employment Socio-economic impact of a sustainable fisheries model. greenpeace.es Index Introduction 3 Methodology 5 Sustainable fisheries model 7 Supporting low scale sustainable fisheries Phasing out of destructive fishing technique Extending the network of marine reserves Moving towards converting deep sea fishing to sustainability Limiting aquaculture operations Developing measures to inform and raise awareness in consumers Complying with biological optimums Controlling pollution in coastal areas Main Results: 13 Global impact on the economy and jobs Impact of the model by sectors of activity Reversing the job loss trend of the current fisheries model Characteristics of employment in fishing communities and the rest of the economy. Type of jobs created in the economy as a whole Conclusions Greenpeace Demands 22 Glossary 24 2 ONBOARD EMPLOYMENT. Introduction European fisheries are facing an The new Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) The reportOnboard employment: unsustainable situation in which regulation approved in May 2013 and Socio-economic impact of a sustainable previously rich, diverse fish effective from January 1st 2014, offers fisheries model proposes a series of the chance to eliminate overfishing measures to be implemented between populations have been decimated and provide an economically viable and 2014 and 2024 and analyses the effects to a fraction of their original size, environmentally sustainable option for they would have on the economy and giving rise to an ecological, social fishermen -

An Alternative Explanation for the Failure of the UNCED Forest Negotiations •

DeborahAn Alternative S. Davenport Explanation for the Failure of the UNCED Forest Negotiations An Alternative Explanation for the Failure of the UNCED Forest Negotiations • Deborah S. Davenport* Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/glep/article-pdf/5/1/105/1819031/1526380053243549.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 In 1990, the United States proposed the negotiation of a global convention to stop deforestation. Negotiations toward a global forest convention (GFC) began under the auspices of the United Nations during preparations for the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), but faltered as this issue became enmeshed in North-South politics. Ultimately, the US-led coali- tion achieved only a non-binding agreement at UNCED: the “Non-legally Bind- ing Authoritative Statement of Principles for a Global Consensus on the Man- agement, Conservation, and Sustainable Development of All Types of Forests” (the Forest Principles). A push to include language in that agreement on revisit- ing the issue of a global convention later was also repelled. Since then, calls have continued for negotiation of a binding global forest convention; to date, anti-convention forces have prevailed. In this paper I analyze the failure of global concern about forests to result in an effective, legally binding international agreement on action to protect them in 1992. I focus here on a legally binding commitment, as opposed to the more common focus on the concept of a “forest regime,” in order to bypass the ongoing controversy among scholars as to whether a global forest regime cur- rently exists in the absence of a legally binding agreement covering this issue area. -

VGP) Version 2/5/2009

Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) VESSEL GENERAL PERMIT FOR DISCHARGES INCIDENTAL TO THE NORMAL OPERATION OF VESSELS (VGP) AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM In compliance with the provisions of the Clean Water Act (CWA), as amended (33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq.), any owner or operator of a vessel being operated in a capacity as a means of transportation who: • Is eligible for permit coverage under Part 1.2; • If required by Part 1.5.1, submits a complete and accurate Notice of Intent (NOI) is authorized to discharge in accordance with the requirements of this permit. General effluent limits for all eligible vessels are given in Part 2. Further vessel class or type specific requirements are given in Part 5 for select vessels and apply in addition to any general effluent limits in Part 2. Specific requirements that apply in individual States and Indian Country Lands are found in Part 6. Definitions of permit-specific terms used in this permit are provided in Appendix A. This permit becomes effective on December 19, 2008 for all jurisdictions except Alaska and Hawaii. This permit and the authorization to discharge expire at midnight, December 19, 2013 i Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 William K. Honker, Acting Director Robert W. Varney, Water Quality Protection Division, EPA Region Regional Administrator, EPA Region 1 6 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, Barbara A. -

Silvicultural Options for Young-Growth Douglas-Fir Forests: the Capitol Forest Study—Establishment and First Results Robert O

United States Department of Silvicultural Options for Young- Agriculture Forest Service Growth Douglas-Fir Forests: Pacific Northwest Research Station The Capitol Forest Study— General Technical Report Establishment and First Results PNW-GTR-598 April 2004 Editors Robert O. Curtis, emeritus scientist, David D. Marshall, research forester, and Dean S. DeBell, (retired), Forestry Sciences Laboratory, 3625-93rd Avenue SW, Olympia, WA 98512-9193. Silvicultural Options for Young-Growth Douglas-Fir Forests: The Capitol Forest Study—Establishment and First Results Robert O. Curtis, David D. Marshall, and Dean S. DeBell, Editors U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station Portland, Oregon General Technical Report PNW-GTR-598 April 2004 Contributors Kamal M. Ahmed, research associate, University of Washington, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Box 352700, Seattle, WA 98195-2700 Hans Andersen, Ph.D. candidate, University of Washington, College of Forest Re- sources, Box 352112, Seattle, WA 98195-3112 Gordon A. Bradley, professor, University of Washington, College of Forest Resources, Box 352112, Seattle, WA 98195-3112 Leslie C. Brodie, forester, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, 3625-93rd Avenue SW, Olympia, WA 98512-9193 Andrew B. Carey, wildlife biologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, 3625-93rd Avenue SW, Olympia, WA 98512-9193 Robert O. Curtis, emeritus scientist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, 3625-93rd Avenue SW, Olympia, WA 98512-9193 Terry A. Curtis, photogrammetry supervisor, forester, Washington Department of Natu- ral Resources, Olympia, WA 98501 Dean S. -

Guide to Oral History Collections in Missouri

Guide to Oral History Collections in Missouri. Compiled and Edited by David E. Richards Special Collections & Archives Department Duane G. Meyer Library Missouri State University Springfield, Missouri Last updated: September 16, 2012 This guide was made possible through a grant from the Richard S. Brownlee Fund from the State Historical Society of Missouri and support from Missouri State University. Introduction Missouri has a wealth of oral history recordings that document the rich and diverse population of the state. Beginning around 1976, libraries, archives, individual researchers, and local historical societies initiated oral history projects and began recording interviews on audio cassettes. The efforts continued into the 1980s. By 2000, digital recorders began replacing audio cassettes and collections continued to grow where staff, time, and funding permitted. As with other states, oral history projects were easily started, but transcription and indexing efforts generally lagged behind. Hundreds of recordings existed for dozens of discreet projects, but access to the recordings was lacking or insufficient. Larger institutions had the means to transcribe, index, and catalog their oral history materials, but smaller operations sometimes had limited access to their holdings. Access was mixed, and still is. This guide attempts to aggregate nearly all oral history holdings within the state and provide at least basic, minimal access to holdings from the largest academic repository to the smallest county historical society. The effort to provide a guide to the oral history collections of Missouri started in 2002 with a Brownlee Fund Grant from the State Historical Society of Missouri. That initial grant provided the seed money to create and send out a mail-in survey. -

Fishing on the Eleven Point River

FISHING ON THE ELEVEN POINT RIVER Fishing the Eleven Point National Scenic River is a very popular recreation activity on the Mark Twain National Forest. The river sees a variety of users and is shared by canoes and boats, swimmers, trappers, and anglers. Please use caution and courtesy when encountering another user. Be aware that 25 horsepower is the maximum boat motor size allowed on the Eleven Point River from Thomasville to "the Narrows" at Missouri State Highway 142. Several sections of the river are surrounded by private land. Before walking on the bank, ask the landowners for permission. Many anglers today enjoy the sport of the catch and fight, but release the fish un-harmed. Others enjoy the taste of freshly caught fish. Whatever your age, skill level or desire, you should be aware of fishing rules and regulations, and a little natural history of your game. The Varied Waters The Eleven Point River, because of its variety of water sources, offers fishing for both cold and warm-water fish. Those fishing the waters of the Eleven Point tend to divide the river into three distinctive areas. Different fish live in different parts of the river depending upon the water temperature and available habitat. The upper river, from Thomasville to the Greer Spring Branch, is good for smallmouth bass, longear sunfish, bluegill, goggle-eye (rock bass), suckers, and a few largemouth bass. This area of the river is warmer and its flow decreases during the summer. The river and fish communities change where Greer Spring Branch enters the river. -

Meramec River Watershed Demonstration Project

MERAMEC RIVER WATERSHED DEMONSTRATION PROJECT Funded by: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency prepared by: Todd J. Blanc Fisheries Biologist Missouri Department of Conservation Sullivan, Missouri and Mark Caldwell and Michelle Hawks Fisheries GIS Specialist and GIS Analyst Missouri Department of Conservation Columbia, Missouri November 1998 Contributors include: Andrew Austin, Ronald Burke, George Kromrey, Kevin Meneau, Michael Smith, John Stanovick, Richard Wehnes Reviewers and other contributors include: Sue Bruenderman, Kenda Flores, Marlyn Miller, Robert Pulliam, Lynn Schrader, William Turner, Kevin Richards, Matt Winston For additional information contact East Central Regional Fisheries Staff P.O. Box 248 Sullivan, MO 63080 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Project Overview The overall purpose of the Meramec River Watershed Demonstration Project is to bring together relevant information about the Meramec River basin and evaluate the status of the stream, watershed, and wetland resource base. The project has three primary objectives, which have been met. The objectives are: 1) Prepare an inventory of the Meramec River basin to provide background information about past and present conditions. 2) Facilitate the reduction of riparian wetland losses through identification of priority areas for protection and management. 3) Identify potential partners and programs to assist citizens in selecting approaches to the management of the Meramec River system. These objectives are dealt with in the following sections titled Inventory, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Analyses, and Action Plan. Inventory The Meramec River basin is located in east central Missouri in Crawford, Dent, Franklin, Iron, Jefferson, Phelps, Reynolds, St. Louis, Texas, and Washington counties. Found in the northeast corner of the Ozark Highlands, the Meramec River and its tributaries drain 2,149 square miles. -

The Protection of Missouri Governors Has Come a Long Way Since 1881, When Governor Thomas Crittenden Kept a .44-Caliber Smith and Wesson Revolver in His Desk Drawer

GOVERNOR’S SECURITY DIVISION The protection of Missouri governors has come a long way since 1881, when Governor Thomas Crittenden kept a .44-caliber Smith and Wesson revolver in his desk drawer. He had offered a $5,000 reward for the arrest and delivery of Frank and Jesse James, and kept the weapon handy to guard against retaliation. In less than a year, Jesse James had been killed, and in October 1882, Frank James surrendered, handing his .44 Remington revolver to Governor Crittenden in the governor’s office. In 1939, eight years after the creation of the Missouri State Highway Patrol, several troopers were assigned to escort and chauffeur Governor Lloyd Stark, and provide security at the Governor’s Mansion for the first family following death threats by Kansas City mobsters. Governor Stark had joined federal authorities in efforts to topple political boss Tom Pendergast. Within a year, Pendergast and 100 of his followers were indicted. In early 1963, Colonel Hugh Waggoner called Trooper Richard D. Radford into his office one afternoon. He told Tpr. Radford to report to him at 8 a.m. the following morning in civilian clothes. At that time, he would accompany Tpr. Radford to the governor’s office. The trooper was introduced to Governor John Dalton and was assigned to full-time security following several threats. Since security for the governor was in its infancy, Tpr. Radford had to develop procedures as he went along. There was no formal protection training available at this time, and the only equipment consisted of a suit, concealed weapon, and an unmarked car. -

Silviculture Strategy in the Kamloops Tsa

TYPE 4 SILVICULTURE STRATEGY IN THE KAMLOOPS TSA SILVICULTURE STRATEGY REPORT Prepared for: Paul Rehsler, Silviculture Reporting & Strategic Planning Officer, Ministry of Natural Resource Operations Resource Practices Branch PO Box 9513 Stn Prov Govt, Victoria, BC V8W 9C2 Prepared by: Resource Group Ltd. 579 Lawrence Avenue Kelowna, BC, V1Y 6L8 Ph: 250-469-9757 Fax: 250-469-9757 Email: [email protected] March 2016 Contract number: 1070-20/FS15HQ090 Type 4 Silviculture Analysis in the Kamloops TSA - Silviculture Strategy STRATEGY AT A GLANCE Strategy at a Glance Historical The annual allowable cut (AAC) in the Kamloops TSA has been set at 4 million m3/year in the 2008 Context TSR 4 and partitioned by species groups: pine, non-pine, cedar and hemlock, and deciduous. Prior to the MPB epidemic the AAC was 2.6 million m3/year, which was increased to a high of 4.3 million m3/year in 2004. Harvesting in the TSA from 2009 to 2013 billed against the AAC has averaged around 2.7 million m3/year. The 2016 AAC Rationale has determined an AAC of 2.3 million m3/year using TSR 5 and this Type 4 Silviculture Strategy as supporting documents. Objective To use forest management and enhanced silviculture to mitigate the mid-term timber supply impacts of mountain pine beetle (MPB) and wildfires while considering a wide range of resource values. General Direct current harvesting into areas of high wildfire hazard and apply a variety of silviculture activities Strategy to mitigate mid-term timber supply and achieve the working targets below. Timber Short-term (1-10yrs): Utilize remaining MPB affected pine through salvage and the Supply: ITSL program.