Sunday, June 28, 2009 Getting with the Program KU Recruits Xavier And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2009 Jordan Brand All-American Team Announced

www.JordanBrandClassic.com Madison Square Garden • New York City • April 18, 2009 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 2009 Jordan Brand All-American Team Announced Madison Square Garden to Host Nation’s Elite High School Basketball Players The top five ESPNU-rated players headline star-filled roster NEW YORK, NY (February 10, 2009) – Jordan Brand, a division of Nike, Inc., announced today during a special ESPNU Selection Show that the top-five ranked ESPNU 100 players – Xavier Henry (Oklahoma City, OK/Memphis), Derrick Favors (Atlanta, GA/Georgia Tech), John Henson (Tampa, FL/North Carolina), DeMarcus Cousins (Mobile, AL/Kentucky) and Renardo Sidney (Los Angeles, CA/USC) – will headline the nation’s best 24 high school senior basketball players at the 2009 Jordan Brand Classic, presented by Foot Locker, at Madison Square Garden on Saturday, April 18 at 8:00 p.m. EST. This year’s event will once again be televised nationally live on ESPN2. The Jordan Brand Classic will also continue to include a regional game, showcasing the top prep players from the New York City metropolitan area in a City vs. Suburbs showdown. In its second year of the event, an International game will tip-off the tripleheader by featuring 16 of the top 17-and-under players from around the world. A portion of the proceeds benefit the New York City-based charity, The Children’s Aid Society. In addition to Henry, Favors, Henson, Cousins and Sidney, the event will also include Kenny Boynton (Plantation, FL/Florida), Avery Bradley (Henderson, NV/Texas), Dominic Cheek (Jersey City, NJ/Villanova), -

Rosters Set for 2014-15 Nba Regular Season

ROSTERS SET FOR 2014-15 NBA REGULAR SEASON NEW YORK, Oct. 27, 2014 – Following are the opening day rosters for Kia NBA Tip-Off ‘14. The season begins Tuesday with three games: ATLANTA BOSTON BROOKLYN CHARLOTTE CHICAGO Pero Antic Brandon Bass Alan Anderson Bismack Biyombo Cameron Bairstow Kent Bazemore Avery Bradley Bojan Bogdanovic PJ Hairston Aaron Brooks DeMarre Carroll Jeff Green Kevin Garnett Gerald Henderson Mike Dunleavy Al Horford Kelly Olynyk Jorge Gutierrez Al Jefferson Pau Gasol John Jenkins Phil Pressey Jarrett Jack Michael Kidd-Gilchrist Taj Gibson Shelvin Mack Rajon Rondo Joe Johnson Jason Maxiell Kirk Hinrich Paul Millsap Marcus Smart Jerome Jordan Gary Neal Doug McDermott Mike Muscala Jared Sullinger Sergey Karasev Jannero Pargo Nikola Mirotic Adreian Payne Marcus Thornton Andrei Kirilenko Brian Roberts Nazr Mohammed Dennis Schroder Evan Turner Brook Lopez Lance Stephenson E'Twaun Moore Mike Scott Gerald Wallace Mason Plumlee Kemba Walker Joakim Noah Thabo Sefolosha James Young Mirza Teletovic Marvin Williams Derrick Rose Jeff Teague Tyler Zeller Deron Williams Cody Zeller Tony Snell INACTIVE LIST Elton Brand Vitor Faverani Markel Brown Jeffery Taylor Jimmy Butler Kyle Korver Dwight Powell Cory Jefferson Noah Vonleh CLEVELAND DALLAS DENVER DETROIT GOLDEN STATE Matthew Dellavedova Al-Farouq Aminu Arron Afflalo Joel Anthony Leandro Barbosa Joe Harris Tyson Chandler Darrell Arthur D.J. Augustin Harrison Barnes Brendan Haywood Jae Crowder Wilson Chandler Caron Butler Andrew Bogut Kentavious Caldwell- Kyrie Irving Monta Ellis -

Utah Jazz Draft Ex-CU Buff Alec Burks

Page 1 of 2 Utah Jazz draft Ex-CU Buff Alec Burks Guard taken 12th to end up a lottery pick By Ryan Thorburn Camera Sports Writer Boulder Daily Camera Posted:06/23/2011 06:57:18 PM MDT Alec Burks doesn't need 140 characters to describe the journey. Wheels up. ... Milwaukee. ... Tired. ... Sacramento. ... Airport life. ... Charlotte. ... Dummy tired. ... Phoenix. ... Thankful for another day. These are some of the simple messages the former Colorado guard sent via Twitter to keep his followers up to date with the journey from Colorado to the NBA. After finishing the spring semester at CU in May, Burks worked out for seven different teams. The Utah Jazz, the last team Burks auditioned for, selected the 6-foot-6 shooting guard with the No. 12 pick. Hoops dream realized. "It was exciting," Burks said during a teleconference from the the Prudential Center in Newark, N.J. not long after shaking NBA commissioner David Stern's hand and posing for photos in a new three-piece suit and Jazz cap. "I'm glad they picked me." A lot of draftniks predicted Jimmer Fredette and the Jazz would make beautiful music together, but the BYU star was taken by Milwaukee at No. 10 -- the frequently forecasted landing spot for Burks -- and then traded to Sacramento. "I don't really believe in the mock drafts," Burks said. "They don't really know what's going to happen. I'm just glad to be in the lottery." Burks, who doesn't turn 20 until next month, agonized over the decision whether to remain in college or turn professional throughout a dazzling sophomore season in Boulder. -

Kansas Basketball Career Statistics

KANSAS BASKETBALL CAREER STATISTICS DON AUTEN • G • 6-1 • 170 • Rochester, N.Y. YR GP MIN MPG FG-A Pct. 3FG-A Pct. FT-A Pct. REB AVG PF AST TO BLK ST PTS AVG ABOUT THE CAREER STATS 1945-46 3 1- 1- 0 3 1.0 The following pages reflect the career statistics of all KU players from 1946-present. 1946-47 10 2- 2- 5 6 0.6 For the most part, points, free throws, field goals and games records have been kept Totals 13 3- 3- 5 9 0.7 since 1946, rebounds since 1955, assists, blocks and steals since 1975 and three- pointers since 1987. LUKE AXTELL • F-G • 6-10 • 220 • Austin, Texas YR GP-GS MIN MPG FG-A Pct. 3FG-A Pct. FT-A Pct. REB AVG PF AST TO BLK ST PTS AVG 1999-00 20-0 323 16.2 54-155 .348 31-79 .392 34-46 .739 55 2.8 20 24 28 7 17 173 8.7 ANRIO ADAMS • G • 6-3 • 190 • Seattle, Wash. 2000-01 19-2 289 15.2 31-83 .373 18-52 .346 20-25 .800 50 2.6 25 17 15 5 8 100 5.3 YR GP-GS MIN MPG FG-A Pct. 3FG-A Pct. FT-A Pct. REB AVG PF AS TO BK ST PTS AVG Totals 39-2 612 15.7 85-238 .357 49-131 .374 54-71 .761 105 2.7 45 41 43 12 25 273 7.0 2012-13 24-0 83 3.5 10-25 .400 2-5 .400 5-13 .385 6 0.3 15 6 11 0 6 27 1.1 UDOKA AZUBUIKE • C • 7-0 • 280 • Delta, Nigeria OCHAI AGBAJI • G • 6-5 • 210 • Kansas City, Mo. -

The WNBA, the NBA, and the Long-Standing Gender Inequity at the Game’S Highest Level N

Utah Law Review Volume 2015 | Number 3 Article 1 2015 Hoop Dreams Deferred: The WNBA, the NBA, and the Long-Standing Gender Inequity at the Game’s Highest Level N. Jeremy Duru Washington College of Law, American University Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.law.utah.edu/ulr Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Law and Gender Commons Recommended Citation Duru, N. Jeremy (2015) "Hoop Dreams Deferred: The WNBA, the NBA, and the Long-Standing Gender Inequity at the Game’s Highest Level," Utah Law Review: Vol. 2015 : No. 3 , Article 1. Available at: http://dc.law.utah.edu/ulr/vol2015/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Utah Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Utah Law Review by an authorized editor of Utah Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOOP DREAMS DEFERRED: THE WNBA, THE NBA, AND THE LONG-STANDING GENDER INEQUITY AT THE GAME’S HIGHEST LEVEL N. Jeremi Duru* I. INTRODUCTION The top three picks in the 2013 Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) draft were perhaps the most talented top three picks in league history, and they were certainly the most celebrated.1 Brittney Griner, Elena Delle Donne, and * © 2015 N. Jeremi Duru. Professor of Law, Washington College of Law, American University. J.D., Harvard Law School; M.P.P. John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University; B.A., Brown University. I am grateful to the Honorable Damon J. Keith for his enduring mentorship and friendship. -

Usbwa Names 2009-10 Men's All-District Teams St

March 9, 2010 For Immediate Release Contact: Joe Mitch 314-421-0339 Standout players and coaches chosen from nine regions USBWA NAMES 2009-10 MEN'S ALL-DISTRICT TEAMS ST. LOUIS (USBWA) – The U.S. Basketball Writers Association has released its 2009-10 Men's All- District Teams, based on voting from its national membership. There are nine regions from coast to coast and a player and coach of the year are selected in each. Following is the entire region-by-region listing: DISTRICT I DISTRICT II DISTRICT III ME, VT, NH, RI, MA, CT NY, NJ, DE, DC, PA, WV VA, NC, SC, MD PLAYER OF THE YEAR PLAYER OF THE YEAR PLAYER OF THE YEAR Jamine Peterson, Providence Scottie Reynolds, Villanova Greivis Vasquez, Maryland COACH OF THE YEAR COACH OF THE YEAR COACH OF THE YEAR Bill Coen, Northeastern Jim Boeheim, Syracuse Gary Williams, Maryland ALL-DISTRICT TEAM ALL-DISTRICT TEAM ALL-DISTRICT TEAM Marqus Blakely, Vermont Lavoy Allen, Temple Al-Farouq Aminu, Wake Forest Keith Cothran, Rhode Island De'Sean Butler, West Virginia Trevor Booker, Clemson Jerome Dyson, Connecticut Austin Freeman, Georgetown Malcolm Delaney, Virginia Tech John Holland, Boston U. Ashton Gibbs, Pittsburgh Devan Downey, South Carolina Matt Janning, Northeastern Jeremy Hazell, Seton Hall Sylven Landesberg, Virginia Jeremy Lin, Harvard Wes Johnson, Syracuse Artsiom Parakhouski, Radford Jamine Peterson, Providence Greg Monroe, Georgetown Jon Scheyer, Duke Stanley Robinson, Connecticut Andy Rautins, Syracuse Kyle Singler, Duke Joe Trapani, Boston College Scottie Reynolds, Villanova Nolan -

Memphis Grizzlies 2016 Nba Draft

MEMPHIS GRIZZLIES 2016 NBA DRAFT June 23, 2016 • FedExForum • Memphis, TN Table of Contents 2016 NBA Draft Order ...................................................................................................... 2 2016 Grizzlies Draft Notes ...................................................................................................... 3 Grizzlies Draft History ...................................................................................................... 4 Grizzlies Future Draft Picks / Early Entry Candidate History ...................................................................................................... 5 History of No. 17 Overall Pick / No. 57 Overall Pick ...................................................................................................... 6 2015‐16 Grizzlies Alphabetical and Numerical Roster ...................................................................................................... 7 How The Grizzlies Were Built ...................................................................................................... 8 2015‐16 Grizzlies Transactions ...................................................................................................... 9 2016 NBA Draft Prospect Pronunciation Guide ...................................................................................................... 10 All Time No. 1 Overall NBA Draft Picks ...................................................................................................... 11 No. 1 Draft Picks That Have Won NBA -

Midseason Top 30 Candidates Announced Today

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Linda Reid, LRPR Cory Hathaway, John R. Wooden Award 310-291-9205 213-630-5231 [email protected] [email protected] 2009-10 JOHN R. WOODEN AWARD® MIDSEASON TOP 30 CANDIDATES ANNOUNCED TODAY Notre Dame’s Harangody, Kentucky’s Patterson and Wall and three Jayhawks head the list LOS ANGELES (Jan. XX, 2010) – The top 30 candidates for the John R. Wooden Award, the nation’s most coveted college basketball honor, were named today by The Los Angeles Athletic Club’s John R. Wooden Award Committee. Composed of the players who will compete for this season’s player of the year award, the attached midseason list is based on individual excellence and team record during the first half of the season. Among the Midseason Top 30 candidates are returning Wooden Award All-American Luke Harangody (2008, 2009) of Notre Dame (the nation’s No .4 scorer at 24.5 ppg) and returning players from last year’s Wooden Award ballot, Sherron Collins (13.8 ppg, 4.2 ast) of Kansas, Duke’s Kyle Singler (15.5 points, 7.4 rebs) and Kalin Lucas of Michigan State (15.7 ppg, 4.1 ast). The list contains 31 players, not the traditional 30, because the playing status of Ohio State’s Evan Turner is uncertain due to a back injury. Three teams have multiple players nominated: No. 1-ranked Kansas (Collins, Cole Aldrich and Xavier Henry, who leads his team in scoring at 16.4 ppg); No. 7 Duke (Singler and John Scheyer) and No. 3 Kentucky (Patrick Patterson and John Wall). -

Lista Dei Giocatori Disponibili

FANTA NBA 2015/2016: LISTA DEI GIOCATORI DISPONIBILI ATLANTA HAWKS Rondae Hollis-Jefferson A Iman Shumpert G Danilo Gallinari A Festus Ezeli C Lance Stephenson G Dennis Schroder G Thaddeus Young A J.R. Smith G Darrell Arthur A Marreese Speights C Pablo Prigioni G Jeff Teague G Thomas Robinson A James Jones G Devin Sweetney A Wesley Johnson G Justin Holiday G Willie Reed A Jared Cunningham G J.J. Hickson A HOUSTON ROCKETS Blake Griffin A Kent Bazemore G Andrea Bargnani C Joe Harris G Joffrey Lauvergne A Corey Brewer G Branden Dawson A Kyle Korver G Brook Lopez C Kyrie Irving G Kenneth Faried A Denzel Livingston G Chuck Hayes A Lamar Patterson G Matthew Dellavedova G Wilson Chandler A James Harden G Josh Smith A Shelvin Mack G CHARLOTTE BOBCATS Mo Williams G Jusuf Nurkic C Jason Terry G Luc Richard Mbah a Moute A Terran Petteway G Aaron Harrison G Quinn Cook G Nikola Jokic C K.J. McDaniels G Paul Pierce A Thabo Sefolosha G Brian Roberts G Anderson Varejao A Oleksiy Pecherov C Marcus Thornton G Cole Aldrich C Tim Hardaway Jr. G Damien Wilkins G Austin Daye A Patrick Beverley G DeAndre Jordan C Al Horford A Elliot Williams G Jack Cooley A DETROIT PISTONS Ty Lawson G DeQuan Jones A Jeremy Lamb G Kevin Love A Adonis Thomas G Will Cummings G LOS ANGELES LAKERS Mike Muscala A Jeremy Lin G LeBron James A Brandon Jennings G Arsalan Kazemi A D'Angelo Russell G Mike Scott A Kemba Walker G Nick Minnerath A Jodie Meeks G Chris Walker A Jabari Brown G Paul Millsap A P.J. -

The Cousins Recruiting Saga Continues (Again) April 2, 2009 Joshua Wright

The Cousins Recruiting Saga Continues (Again) April 2, 2009 Joshua Wright It wasn’t too long ago that I blogged about the purported end of the Demarcus Cousins saga. For TOTM readers that want to catch up to speed, here is how things stood about a month ago: For those who haven’t, Cousins is a blue chip high school basketball recruit who has been bargaining hard with the University of Alabama-Birmingham (UAB) over signing his National Letter of Intent — the letter that commits a player to attend the university and imposes the penalty of giving up a full year of eligibility if the student-athlete transfers. Cousins wants to commit to UAB to play for former Indiana University coach Mike Davis but wanted to seek contractual insurance for the possibility that after signing the letter of intent and making specific investments to UAB, Davis might leave the program. Cousins alleged that Davis promised that UAB would release Cousins without penalty if Davis was no longer his coach. When we last left Cousins, he was holding out, talking to other programs, and attempting to bargain for this term in his National Letter of Intent. He’s now signed with Memphis. Back then, I noted that I thought it was odd that UAB could not find a way to include the contractual provision in Cousins’ NLI and wondered whether other athletes were successful in doing so. It turns out recent developments give answer to that question, and also involve Cousins. As the college basketball world now knows, former Memphis coach John Calipari (who successfully got the verbal commitment from Cousins) has accepted the head coaching position at the University of Kentucky. -

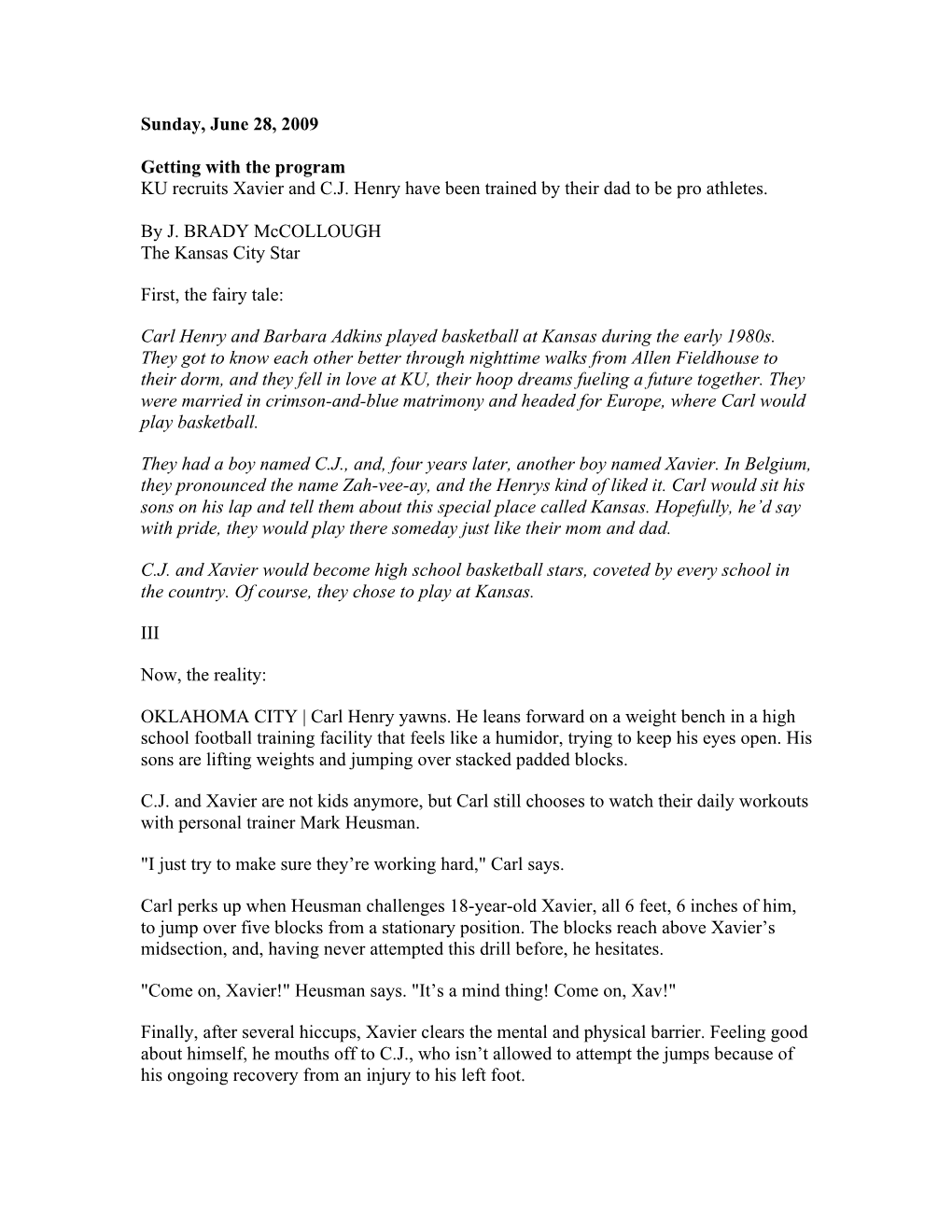

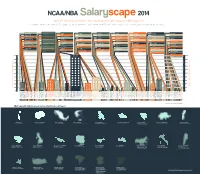

A Complete Breakdown of Every NBA Player's Salary, Where They

$1,422,720 (DonatasMotiejunas,Houston) $3,526,440 (JonasValanciunas,Toronto) Lithuania: $4,949,160 $12,350,000 (SergeIbaka,OklahomaCity) $3,049,920 (BismackBiyombo,Charlotte) Congo: $15,399,920 Total Salaries of Players that Schools Produced in Millions of US Dollars 100M 120M 140M 160M 180M 200M NBA Salary Distribution by Country that Produced Players SalaryDistributionbyCountrythatProduced NBA 20M 40M 60M 80M 947,907 (OmriCasspi,Houston) Israel: $947,907 0M 3 $10,105,855 |Gerald Wallace, Boston $3,250,000 |Alonzo Gee, Cleveland $2,652,000 |Mo Williams, Portland $3,135,000 |Jerryd Bayless, Boston Arizona $1,246,680 |Solomon Hill, Indiana $12,868,632 |Andre Iguodala, Golden State $3,500,000 |Jordan Hill, LA Lakers 10 $6,400,000 |Channing Frye Phoenix $5,625,313 |Jason Terry, Sacramento $5,016,960 |Derrick Williams, Sacramento $5,000,000 |Chase Budinger, Minnesota $226,162 |Mustafa Shaku, Oklahoma City $11,046,000 |Richard Jefferson, Utah Butler Bucknell Brigham Young Boston College Blinn College|$1.4M Belmont |$0.5M Baylor |$7.1M Arkansas-LR |$0.8M Arkansas |$23.1M Arizona State|$16M Arizona |$54M Alabama |$16M 3 $510,000 |Carrick Felix, Cleveland $13,701,250 |James Hardin, Houston $1,750,000 |Jeff Ayres, San Antonio 3 21,466,718 |Joe Johnson 884,293 |Jannero Pargo, Charlotte 1 788,872 |Patrick Beverey, Houston 884,293 |Derek Fisher, Oklahoma City A completebreakdownofeveryNBAplayer’ssalary,wheretheyplayedbeforetheNBA,andwhichschoolscountriesproducehighestnetsalary. 4 4,469,548 |Ekpe Udoh, Milwaukee 788,872 |Quincy Acy, Sacramento 788,872 -

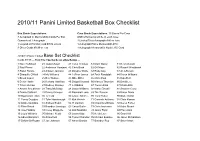

2010/11 Panini Limited Basketball Box Checklist

2010/11 Panini Limited Basketball Box Checklist Box Break Expectations: Case Break Expectations: 15 Boxes Per Case 3 Autograph or Memorabilia Cards Per Box ONE of following will be in each case: Guaranteed 1 Autograph 1 Limited Trios Autograph #/49 or less 1 Legend or Parallel Card #/199 or less 1 Autograph Prime Memorabilia #/10 3 Other Cards #/199 or less 1 Autograph Memorabilia Rookie RC Card 2010/11 Panini Limited Base Set Checklist Cards #/199 --- Find The Top Cards on eBay Below --- 1 Nate Robinson 21 Joakim Noah 41 Tyrus Thomas 61 Marc Gasol 81 Kevin Durant 2 Paul Pierce 22 Anderson Varejoao 42 Chris Bosh 62 OJ Mayo 82 Russell Westbrook 3 Rajon Rondo 23 Antawn Jamison 43 Dwyane Wade 63 Rudy Gay 83 Al Jefferson 4 Shaquille O'Neal 24 Mo Williams 44 LeBron James 64 Zach Randolph 84 Deron Williams 5 Brook Lopez 25 Ben Wallace 45 Mike Miller 65 Chris Paul 85 Raja Bell 6 Devin Harris 26 Richard Hamilton 46 Dwight Howard 66 Marcus Thornton 86 David Lee 7 Travis Outlaw 27 Rodney Stuckey 47 JJ REdick 67 Trevor Ariza 87 Monta Ellis 8 Amare Stoudemire 28 Tracy McGrady 48 Jason Williams 68 Manu Ginobili 88 Stephen Curry 9 Danilo Gallinari 29 Danny Granger 49 Rashard Lewis 69 Tim Duncan 89 Baron Davis 10 Raymond Felton 30 TJ Ford 50 JaVale McGee 70 Tony Parker 90 Blake Griffin 11 Toney Douglas 31 Tyler Hansbrough 51 Kirk Hinrich 71 Carmelo Anthony 91 Chris Kaman 12 Andre Iguodala 32 Andrew Bogut 52 Yi Jianlian 72 Chauncey Billups 92 Derek Fisher 13 Elton Brand 33 Brandon Jennings 53 Caron Butler 73 Chris Andersen 93 Kobe Bryant 14 Jrue Holiday