Download/Djado D E.Pdf>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dear Shareholders!

Dear Shareholders! It is a great pleasure for me that I can share with you again the results of a truly successful business year: sales volumes of our flagship brand, Unicum, increased yet again, our Hubertus brand continued its march forward, our Fütyülős brand maintained its good market position and, besides all these, the international brands marketed by the Company can also boast a considerable increase. Perhaps the most important event in the life of Zwack Unicum last year was the January 2017 debut of Unicum Riserva which was the first innovation not only in Hungary, but also in Europe, to enter the super-premium herb liqueur mar- ket. This very special brand owes its unique taste to the „double barrel” ageing process: Unicum, which serves as its base, is aged in the biggest and oldest - over 80 years old - cask in the cellars in Soroksári street. This is followed by the ageing in barrels from the cellars of Tokaj. Unicum Riserva was introduced to representatives of the spirits market and the press with the help of our master distillers during our renewed mentor programs, meeting with a huge success. The main theme of summer 2017 was water and water sports. In line with that, we presented a very special life story which can serve as an example for all those who are looking for motivation in order to achieve their goals. Swimmer Tamas Sors, multiple paralympic world and European champion, is a living proof of how much we can achieve by a positive attitude, dedication and hard work. No summer passes by without festivals and Unicum. -

Just Amaro Or What Else? Herb Based Amari Stand in the Breach Again

Just amaro or what else? Herb based amari stand in the breach again Herb based liqueurs and bitters date back to the age of the early conventual pharmacies. Some of them, with time, have become world famous classics. And now they come back to fashion in bars. By Erhard Ruthner After a good meal a “drop” is compulsory: an ancient wisdom of our grandfathers that still finds its followers, even if the digestive effect of alcohol is not proved in medicine, but rather it is part of everlasting legends. What on the contrary is universally known is the relaxing effect that herbs have on the gastrointestinal part; it’s no wonder, therefore, that herb based liqueurs and amari have an ancient history. It is the case of the hospital of Salerno, the forerunner of the first pharmaceutical shops. But also the Benedictine monks of Montecassino had known the secrets of the processing of herbs to produce tinctures and liqueurs since the origins. Many liqueurs produced and requested still today really have their roots in the pharmacies of the monasteries: from France the Bénédectine and the Chartreuse, from Italy Averna and from Germany the elixirs of the distillery of Andechs. But even later it was the pharmacists that opened the way – in particularly in Northern Italy at the beginning of the nineteenth century – to the golden age of herbs among drink makers: names as Ausano Ramazzotti, Gaspare Campari, Maria Branca, Francesco Peloni (Bràulio) or even Benedetto Carpano, who was the creator of vermouth with his idea of flavoring wine. Also Johann Becher and József Max Zwack started to commercialize the recipes of their families in Austria-Hungary, and still today Becherovka and Unicum are considered typical national drinks in the Check Republic and Hungary. -

KMBT C554e-20150630165533

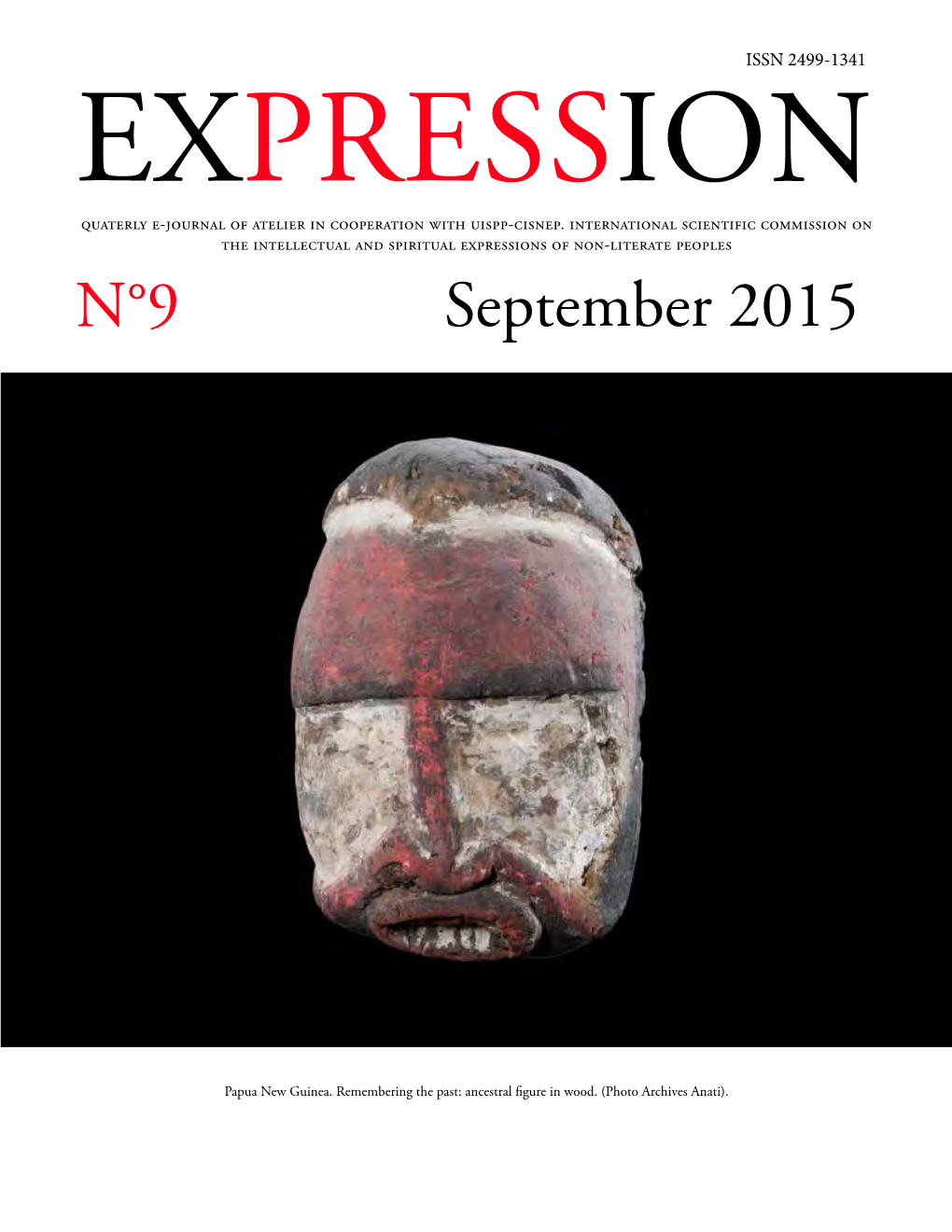

Recent Research on Paleolithic Arts in Europe and the Multimedia Database Cesar Gonzalez Sai 民 Roberto Cacho Toca Department Department of Historical Sciences. University of Cantabria. Avda. Los Castros s/n. 39005. SANTANDER (Spain) e-mail: e-mail: [email protected] I [email protected] Summary. In In this article the authors present the Multimedia Photo YR Database, made by Texnai, Inc. (Tokyo) and the the Department of Historical Sciences of the University of Cantabria (Spain) about the paleolithic art in northern northern Spain. For this purpose, it ’s made a short introduction to the modem knowledge about the European European paleolithic art (35000 ・1 1500 BP), giving special attention to the last research trends and, in which way, the new techniques (computers, digital imaging, database, physics ... ) are now improving the knowledge about this artistic works. Finally, is made a short explanation about the Multimedia Photo YR Database Database and in which way, these databases can improve, not only research and teaching, but also it can promote in the authorities and people the convenience of an adequate conservation and research of these artistic artistic works. Key Words: Multimedia Database, Paleolithic Art, Europe, North Spain, Research. 1. 1. Introduction. The paleolithic European art. Between approximately 35000 and 11500 years BP, during the last glacial phases, the European continent continent saw to be born a first artistic cycle of surprising surprising aesthetic achievements. The expressive force force reached in the representation of a great variety of of wild animals, with some very simple techniques, techniques, has been rarely reached in the history of the the western a此 We find this figurative art in caves, caves, rock-shelters and sites in the open air, and at the the same time, on very di 仔erent objects of the daily li た (pendants, spatulas, points ofjavelin, harpoons, perforated perforated baton, estatues or simple stone plates). -

Palaeoart of the Ice Age

Palaeoart of the Ice Age Palaeoart of the Ice Age By Robert G. Bednarik Palaeoart of the Ice Age By Robert G. Bednarik This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Robert G. Bednarik All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-9517-2 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-9517-0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Outlining the Issues Introduction ............................................................................................ 1 The nature of palaeoart .......................................................................... 3 About this book ...................................................................................... 6 About Eve .............................................................................................. 9 Summing up ......................................................................................... 21 Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 37 Africa Earlier Stone Age (ESA) and Lower Palaeolithic ............................... -

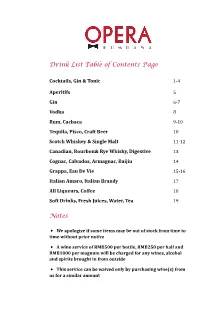

Drink List Table of Contents Page Notes

Drink List Table of Contents Page Cocktails, Gin & Tonic 1-4 Aperitifs 5 Gin 6-7 Vodka 8 Rum, Cachaca 9-10 Tequila, Pisco, Craft Beer 10 Scotch Whiskey & Single Malt 11-12 Canadian, Bourbon& Rye Whisky, Digestive 13 Cognac, Calvados, Armagnac, Baijiu 14 Grappa, Eau De Vie 15-16 Italian Amaro, Italian Brandy 17 All Liqueurs, Coffee 18 Soft Drinks, Fresh Juices, Water, Tea 19 Notes • We apologize if some items may be out of stock from time to time without prior notice • A wine service of RMB500 per bottle, RMB250 per half and RMB1000 per magnum will be charged for any wines, alcohol and spirits brought in from outside • This service can be waived only by purchasing wine(s) from us for a similar amount Cocktails Signature Cocktails Marilyn's Tear 98 Limoncetta Crema, Malibu, Lemon Juice, Egg White Opera Negroni 128 Tanqueray Gin, Sweet Vermouth, Campari, Barolo Chinato, Unicum Opera Royal 138 Sparkling Wine, Massenez Fruit Cream, Sorbet Opera Old Fashioned 188 Diplomatico Rum, Bitters, Soda, Chocolate, Luxardo Cherry Classic Cocktails Mojito 78 Light Rum, Lime Juice, Mint Sprigs, Sugar, Soda Water Manhattan78 Bourbon Whisky, Sweet Vermouth, Bitters Americano78 Campari, Sweet Vermouth, Soda Water Bloody Mary 78 Vodka, Tomato Juice, Tabasco, Pepper, Lemon Juice Vesper Martini 78 Vodka, Lillet Blanc, Gin Moscow Mule 88 Vodka, Lime Juice, Fresh Ginger, Ginger Beer Old Fashioned 88 Bourbon Whisky, Bitters, Soda Amber Dream 128 Gin, Sweet Vermouth, Chartreuse, Orange Bitters 1 All prices are in Rmb and subject to 10% service charge Cocktails Sour -

Library-Of-Distilled-Spirits-Beverages.Pdf

PAGE 3 CLASSIC COCKTAIL RECOMMENDATIONS & STAFF SIGNATURES NEW YORK SOUR 12 Wild Turkey 101 Lemongrass Syrup Lemon Juice Cabernet Sauvignon CLASSIC COCKTAIL VESPER MARTINI 12 RECOMMENDATIONS Tanquerey Gin St. George California Citrus Vodka Cocchi Americano Vermouth GIMLET 12 Navy Strength Plymouth Gin Lime Cordial HEMINGWAY DAIQUIRI 12 Caña Brava Carta Blanca 3y Rum Luxardo Maraschino Liqueur 1.0 Lime juice Grapefruit Juice Simple Syrup SOUTH SIDE 12 Fords Gin Lime Juice Simple Syrup mint leaves Soda TOMMY’S MARGARITA 12 Cabeza Blanco Tequila Iime juice agave syrup MANHATTAN COCKTAIL Old Formula #2 Rittenhouse 100˚ rye whiskey Dolin Rouge sweet vermouth Grand Marnier Angostura bitters Lemon twist MAI TAI 12 Appleton Signature Rum Rhum Clement VSOP Lime Juice Orgeat syrup CLASSIC COCKTAIL Pierre Ferrand Dry Curacao RECOMMENDATIONS SAZERAC 12 Rittenhouse Rye Demerara syrup Peychauds Bitters Angostura Bitters FRENCH 75 13 Pierre Ferrand 1840 Cognac lemon juice simple syrup WESTERN ADDITION 13 Tapatio Blanco Tequila Rhubarb Sauce Madagascar Peppercorn Tincture Verjus Blanc Simple Syrup STAFF Sparkling Sake SIGNATURES PISCO SOUR #2 12 Barsol Pisco Italia Lime Juice Pineapple Syrup Egg white VAUVERT SWIZZLE 13 Charbay Green Tea Vodka Green Chartreuse Lemon Juice Grapefruit Juice Honey Syrup Orange Blossom Water CHERRY COBBLER 12 Amontillado Sherry Maurin Quina Sour Cherry Syrup Lemon Juice PORT ROYAL 14 Banks 7 rum Plantation OFTD rum Black Truffle Honey Angostura Orange Bitters Angostura Bitters SUMMER BOULEVARDIER 13 Four Roses Small Batch Bourbon Dolin Blanc Campari THE FIRST DUKE OF NORMANDIE 12 Calvados Lemon Juice PAGE 7 BOURBON BOURBON - THE COCKTAILS BOURBON BOULEVARDIER 14 PAPER PLANE 12 Willett Pot Still, Dolin Buffalo Trace, Amaro Rouge, Campari Nonino, Aperol, Lemon BROWN DERBY 12 WHISKEY COLLINS 12 Old Forester, Four Roses, Lemon, Grapefruit, Honey Simple, Soda GOLD RUSH 12 WHISKEY DAISY NO. -

Turismo En Las Cuevas: El Patrimonio Rupestre En Cantabria, España Cave Tourism

Gran Tour: Revista de Investigaciones Turísticas nº 16 Julio-Diciembre de 2017 p.78-94 ISSN: 2172-8690 Escuela Universitaria de Turismo, Universidad de Murcia TURISMO EN LAS CUEVAS: EL PATRIMONIO RUPESTRE EN CANTABRIA, ESPAÑA CAVE TOURISM: ROCK ART HERITAGE IN CANTABRIA, SPAIN FRANCESC FUSTÉ-FORNÉ1 Facultad de Turismo, Universitat de Girona RESUMEN Desde el descubrimiento de las primeras cavidades, la relación entre arqueología y turismo en estos espacios ha evolucionado teniendo en cuenta varios aspectos de forma simultánea, entre los cuales la conservación y el desarrollo sostenible del entorno han sido primordiales. A la vez, la activación turística de estos espacios es un eje estratégico para el desarrollo rural. Este artículo analiza la importancia del turismo en cuevas en Cantabria, que aglutina la mayor densidad de cuevas de arte rupestre del mundo. Para visitantes y turistas, este tipo de turismo tiene un atractivo tanto cultural como natural. Palabras clave: arte rupestre, cuevas, espacios naturales, España, turismo arqueológico, turismo rural. ABSTRACT From the discovery of a cave, the relationship between archaeology and tourism primarily considers issues such as conservation and sustainable development. Also, tourism activity later performs as strategic driver for rural development. This paper analyses the role of cave tourism in Cantabria, which agglutinates the world’s major density of caves. To visitors and tourists, motivations for cave tourism come from both cultural and natural factors. Key words: rock art, caves, natural areas, Spain, archaeological tourism, rural tourism. Fecha de Recepción 3 de noviembre 2017. Fecha de Aceptación 22 de diciembre 2017 1 Facultad de Turismo, Universitat de Girona. -

MS Royal Crown

MS Royal Crown Bar Menu Open White Wine Gruener Veltliner, dry 0.2 l 4.40 € Gmeiner Weissburgunder, dry 0.2 l 4.40 € Brogsitter Open Rosé Wine Rosa; Rosé, dry 0.2 l 4.40 € Strehn Open Red Wine Zweigelt, dry 0.2 l 4.40 € Gmeiner Spätburgunder, dry 0.2 l 4.40 € Brogsitter Ingredients / Allergens – Sulfites Soft Drinks Gerolsteiner Sparkling Water 0.25 l 2.40 € Gerolsteiner Still Water 0.25 l 2.40 € Gerolsteiner Sparkling Water 0.75 l 4.60 € Gerolsteiner Still Water 0.75 l 4.60 € Coca-Cola / Light 0.33 l 3.90 € Fanta 0.33 l 3.90 € Sprite / Light 0.33 l 3.90 € Bitter Lemon 0.20 l 3.60 € Ginger Ale 0.20 l 3.60 € Tonic Water 0.20 l 3.60 € Apple Juice 0.30 l 2.60 € Orange Juice 0.30 l 2.60 € Tomato Juice 0.30 l 2.60 € Cranberry Juice 0.30 l 2.60 € Pineapple Juice 0.30 l 2.60 € Grapefruit Juice 0.30 l 2.60 € All prices include VAT. Sparkling Wine / Champagne Sparkling House Wine, dry 0.10 l 3.70 € Sparkling House Wine, dry 0.75 l 22.50 € Mumm Piccolo 0.20 l 7.50 € Champagne Gobillard Tradition Brut Blanc 0.75 l 71.00 € Hot Drinks Coffee, Espresso 2.70 € Cappuccino 3.50 € Tea assortment 2.70 € Hot Chocolate 3.50 € Beer Veltins beer, draft 0.30 l 3.50 € Veltins beer, draft 0.40 l 4.10 € Veltins beer, bottle 0.33 l 3.90 € Shandy 0.30 l 3.50 € Shandy 0.40 l 4.10 € Köstritzer dark beer, bottle 0.33 l 3.90 € Franziskaner wheat beer, bottle 0.50 l 4.90 € Gösser, bottle 0.33 l 4.60 € Stiegl, bottle 0.33 l 4.70 € Veltins non alcoholic beer, bottle 0.33 l 3.90 € Aperitifs Aperol 4 cl 3.60 € Campari 4 cl 4.70 € Martini Bianco / Rosso / Dry 4 cl 4.20 € Porto Sandeman Fine Ruby 5 cl 4.20 € Porto Sandeman Fine White 5 cl 4.20 € Sherry Medium 5 cl 4.20 € Sherry Tio Pepe Dry 5 cl 4.40 € Pernod 4 cl 4.20 € Pimm´s No. -

Course Descriptions Tourism (514.08

COURSE DESCRIPTIONS Bachelor’s Degree in Tourism 1st year 6750 PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS PART I: INTRODUCTION TO THE ECONOMY Lesson 1: Fundamentals of the economy. 1.1. Concept y method in economics. 1.2. Scarcity and need to choose: the frontier of production possibilities. 1.3. Resource assignation in a market economy system. 1.4. Efficiency, market failure and the State. PART II: MICROECONOMY Lesson 2: Demand, offer, and price. 2.1. Demand. 2.2. Offer. 2.3. Market balance. 2.4. Applications of demand and offer analysis. Lesson 3: Elasticity and its applications. 3.1. Demand elasticity. 3.2. The elasticity of offer. 3.3. Applications of elasticity in demand and offer. Lesson 4: The firm: production and costs. 4.1. Basic concepts. 4.2. The productive activity of the firm. 4.3. Production costs. Lesson 5: Perfect competition. 5.1. Characteristics of competitive models. 5.2. Short-term competitive equilibrium. Lesson 6: Non-competitive markets. 6.1. The monopoly. 1 6.2. Monopolistic competition. 6.3. The oligopoly. PART III. MACROECONOMY Lesson 7. NATIONAL ACCOUNTING AND BASIC MACRO-ECONOMIC PROBLEMS. 7.1. The objectives of the macroeconomy. 7.2. Gross National Product (GNP). Estimation methods. 7.3. Nominal GDP and economic growth rate. 7.4. Balance of Payments and exchange rates. Lesson 8. THE ASSETS MARKET AND FISCAL POLICY. 8.1. The components of aggregate demand. 8.2. The Keynesian model of income determination. 8.3. Tax policy. Lesson 9. THE MONEY MARKETS AND MONETARY POLICY. 9.1. Concept and functions of money. 9.2. Demand for money and monetary offer. -

Breakfast Specials Breakfast Specials

BREAKFAST SPECIALS BREAKFAST SPECIALS HOUSE-MADE QUICHE | $13 HOUSE-MADE QUICHE | $13 bacon, mozzarella, tomatoes, garlic bacon, mozzarella, tomatoes, garlic FENNEL SAUSAGE SCRAMBLE | $15 FENNEL SAUSAGE SCRAMBLE | $15 fennel sausage, basil, mozzarella, red peppers, fresh basil fennel sausage, basil, mozzarella, red peppers, fresh basil served with cottage potatoes & served with cottage potatoes & your choice of toast your choice of toast CHICKEN & BISCUIT | $16 CHICKEN & BISCUIT | $16 fried chicken thigh, house-made buttermilk biscuit, fried chicken thigh, house-made buttermilk biscuit, spicy honey butter & an over easy egg* spicy honey butter & an over easy egg* served with cottage potatoes served with cottage potatoes TO THE BOTTLE WE GO TO THE BOTTLE WE GO VIETTI MOSCATTO D’ ASTI CASCINETTA | $8 VIETTI MOSCATTO D’ ASTI CASCINETTA | $8 break free from the tradition of mimosas and bloody break free from the tradition of mimosas and bloody Mary's and try a glass of Moscatto. intense aromas of Mary's and try a glass of Moscatto. intense aromas of peaches, rose petals and ginger. on the palate it is peaches, rose petals and ginger. on the palate it is delicately sweet and sparkling delicately sweet and sparkling MIMOSA | $8 MIMOSA | $8 fresh squeezed orange and sparkling wine fresh squeezed orange and sparkling wine or make it an Irish Mimosa with Mcmenamins’ own Irish Stout or make it an Irish Mimosa with Mcmenamins’ own Irish Stout sub peach or grapefruit for 1/2 a buck sub peach or grapefruit for 1/2 a buck SIGNATURE TAVERN COFFEE | $9 -

Results by Class 2000 Vodka Flavored Vodka

2000 RESULTS BY CLASS Double Gold Medal, Clear Creek Williams Pear Eau-de-Vie, Oregon, United States [40%] $32. Bronze Medal, Clear Creek Blue Plum Eau-de-Vie, Oregon, United States [40%] $32. VODKA Best Vodka, Double Gold Medal, Pearl Vodka, Western Alberta, Canada [40%] $25 / Ltr.. Importer: Pearl Spirits - Mill Valley, CA Double Gold Medal, Monopolowa Vodka, J.A. Baczewski Monopolowa, Austria [40%] $12. Importer: Mutual Wholesale Liquor - LA, CA Double Gold Medal, Vox Vodka, Netherlands, Holland [40%] $30. Importer: Jim Beam Brands - Deerfield, IL Double Gold Medal, Kremlyouskaya Vodka, De Luxe, Russia [40%] $20. Importer: Dozortsev & Sons - NY Double Gold Medal, Wodka Wyborowa Vodka, Poland [40%] $18. Importer: Austin, Nichols & Co. - NY Double Gold Medal, Belvedere Vodka, Poland [40%] $30. Importer: Millennium Import - Minneapolis, MN Double Gold Medal, Gvori Vodka, Polish Luxury , Poland [40%] $20. Importer: Beverage Brands - Roswell, GA Gold Medal, Finlandia Vodka, Finland [40%] $17. Importer: Brown-Forman - Louisville, KY Gold Medal, Fris Vodka, Denmark [40%] $16. Importer: Brittany Imports - Miami, FL Silver Medal, Svedka Vodka, Sweden [40%] $12. Importer: Spirits Marque One - NY Silver Medal, Rain Vodka, United States [40%] $21. Silver Medal, Three Olives Vodka, England [40%] $23. Importer: White Rock Distilleries - Lewiston, ME Silver Medal, Five O'Clock Vodka, United States [40%] $8. www.lairdandcompany.com Silver Medal, Thor's Hammer Vodka, Sweden [40%] $26. Importer: Barton Imports - Chicago, IL Silver Medal, Olifant Vodka, Holland [40%] $16. Importer: Allied Spirits & Wines - Avon, CT Silver Medal, Chopin Vodka, Poland [40%] $30. Importer: Millennium Import - Minneapolis, MN Silver Medal, Vincent Vodka, Holland [40%] $30. Importer: Luctor International - Reno, NV Silver Medal, Hamptons Vodka, Minnesota, United States $30. -

Drinks Like These

The Italian tradition of aperitivo – that magical, transitory drinking time that bridges the gap between work and dinner is filled with low alcohol drinks like these Milano-Torino 9 Campari, Cocchi Vermouth di Torino. Asti Aperitivi 9 Cocchi Americano, tonic, soda. Giostra d’Alcol 9 Barbera d’Asti wine, Campari, honey, Pellegrino Limonata. Americano 9 Campari, Vermouth, soda. A Point and a Half Spritz 11 “The spritz is more Punt e Mes, Martini & Rossi Bianco, Prosecco, balsamic vinegar, soda. than a cultural way of enjoying life; the spritz Bianco House Spritz 11 Cocchi Americano, Rose Cava, is a mantra, an attitude grapefruit juice, soda. and a state of being” Carducci Spritz 11 Zwack Amaro, Prosecco, Pellegrino Aranciata. – Talia Baiocchi La Notte Spritz 11 Aperol, Cocchi Rosa, Tanquaray 10 gin, Prosecco, soda. Pirlo (aka The Brescia Spritz) 11 Campari, dry white wine, soda. Olive The Lights Spritz 11 Aperol, Meletti Amaro, Prosecco, lemon, Castelvetrano olive brine. Spritz Veneziano (aka Venetian Spritz, aka Aperol spritz) 11 Aperol, Prosecco, soda. Negroni 12 Beefeater Gin, Campari, Cocchi Vermouth di Torino. Negroni Bianco 12 Bombay Sapphire Gin, Luxardo Bitter Bianco, Lillet Blanc. Negroni Sbagliato (aka The ‘Mistaken’ Negroni) 12 Campari, Carpano Antica, Prosecco. Strawberry Negroni 12 Tanqueray 10 Gin, Strawberry-infused Campari, Cinzano Vermouth Bianco. Avanvera 12 Cocchi Vermouth di Torino, Vecchia Romagna Brandy, Strega. Bitter Intentions 12 Carpano Antica, Campari, lemon, soda. Howard Street Smoke Show 16 Laphroaig Scotch Whiskey, Vecchio Amaro del Capo, Nastro D’Oro Nocino, smoke. Created as an homage to the lost historical fact that Rice Howard Way is actually an amalgam of the old Howard Street (101A st) and Rice Avenue (101 ave) Three Coins in the Fountain 12 Campari, Dolin Blanc Vermouth de Chambery, lime, soda.