View PDF Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philanthropy: the Power of Giving UGS 303

Philanthropy: The Power of Giving UGS 303 Spring 2018 Professor: Pamela Paxton Class Meetings: Mondays and Wednesdays 12:00-1:00, Friday discussion sections Classroom: CLA 1.106 Office Hours: Wednesdays 1:00-2:00 or by appointment Office: CLA 3.738 Office Phone: (512) 232-6323 Email: [email protected] To give away money is an easy matter in any man’s power. But to decide to whom to give it, and how large and when, and for what purpose and how, is neither in every man’s power nor an easy matter. Hence it is that such excellence is rare, praiseworthy and noble. --Aristotle, Ethics, 360 BC Course Description: Who gives? Who volunteers? Does it matter? This course will cover the scope and diversity of the nonprofit sector, as well as individual patterns of giving and volunteering. Further, although billions of dollars are distributed by individuals and charitable foundations each year, only some charitable programs are effective. Thus, a portion of the course will focus on providing students with the tools and skills to evaluate charitable programs for effectiveness. Based on their own evaluations, students will have the opportunity to distribute significant funds (provided through The Philanthropy Lab and individual donors) to charitable organizations. Students will be placed into groups that will research, discuss, and debate charities, with the whole class determining the ultimate distribution of the funds. Course Materials: Peter Singer. 2009. The Life You Can Save. New York: Random House. Available at University Co- op. Other course readings available through Canvas. Course Requirements and Grading: Class Participation (10%) As in all college courses, students should come to class having read and thought about the assigned readings. -

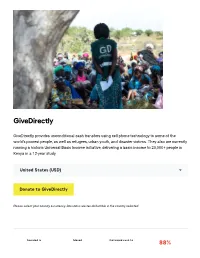

Givedirectly

GiveDirectly GiveDirectly provides unconditional cash transfers using cell phone technology to some of the world’s poorest people, as well as refugees, urban youth, and disaster victims. They also are currently running a historic Universal Basic Income initiative, delivering a basic income to 20,000+ people in Kenya in a 12-year study. United States (USD) Donate to GiveDirectly Please select your country & currency. Donations are tax-deductible in the country selected. Founded in Moved Delivered cash to 88% of donations sent to families 2009 US$140M 130K in poverty families Other ways to donate We recommend that gifts up to $1,000 be made online by credit card. If you are giving more than $1,000, please consider one of these alternatives. Check Bank Transfer Donor Advised Fund Cryptocurrencies Stocks or Shares Bequests Corporate Matching Program The problem: traditional methods of international giving are complex — and often inefficient Often, donors give money to a charity, which then passes along the funds to partners at the local level. This makes it difficult for donors to determine how their money will be used and whether it will reach its intended recipients. Additionally, charities often provide interventions that may not be what the recipients actually need to improve their lives. Such an approach can treat recipients as passive beneficiaries rather than knowledgeable and empowered shapers of their own lives. The solution: unconditional cash transfers Most poverty relief initiatives require complicated infrastructure, and alleviate the symptoms of poverty rather than striking at the source. By contrast, unconditional cash transfers are straightforward, providing funds to some of the poorest people in the world so that they can buy the essentials they need to set themselves up for future success. -

A Global Approach to Ethics

A Global Approach to Ethics PETER SINGER Born in Melbourne, Australia, in 1946, and educated at the University of Melbourne and at Oxford University, he has taught at Oxford, La Trobe, and Monash Universities. Since 1999 he has been Ira W. DeCamp Professor of Bioethics in the University Center for Human Values at Princeton University. From 2005 he has also held the part-time position of Laureate Professor at the University of Melbourne, in the Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics. Peter Singer first became recognized internationally after the publication of Animal Liberation in 1975. Subsequently, he has written many books including: Practical Ethics; The Expanding Circle; How Are We to Live?; The Ethics of What We Eat (with Jim Mason); and most recently, The Life You Can Save. A NEw wORLD poration to pay to clean it up, and compensate when the United those affected. If that is a fair principle—that States and For most of the eons of human existence, people the polluter should pay, that those who cause the living only short distances apart might as well, problem are responsible for fixing it—then the de- Australia refused for all the difference they made to each other’s veloped nations should be paying the costs of to sign the Kyoto lives, have been living in separate worlds. A river, global warming. They are not only the biggest Protocol, they a mountain range, a stretch of forest or desert, a polluters now, they have been for the past cen- were making other sea—those were enough to cut people off from tury or more. -

Ethics Matter: a Conversation with Peter Singer

Ethics Matter: A Conversation with Peter Singer http://www.carnegiecouncil.org/resources/transcripts/0435.html/:pf_print... Ethics Matter: A Conversation with Peter Singer Peter Singer , Julia Taylor Kennedy October 6, 2011 Introduction Remarks Questions and Answers Introduction JULIA KENNEDY: I'm Julia Taylor Kennedy, program officer here at the Council. I wanted to also welcome everyone who's watching our webcast today. Peter Singer I'm looking forward to a really great town hall discussion. We've had a lot of great back-and-forths in our first couple of these, and so we're looking forward to hearing your insights and questions in the second half of today's program. When we here at the Carnegie Council drew up our wish list of scholars to bring as part of this series Ethics Matter, philosopher Peter Singer sat at the very top. I could spend this entire session telling you about his extensive publishing and lecturing career. But I do want to give him a chance to speak, so instead here are a few highlights. He was educated at the University of Melbourne and the University of Oxford. He is Julia Taylor Kennedy currently on faculty at Princeton University and the University of Melbourne and has taught many other places. He became well known internationally after publishing Animal Liberation in 1975, which has been called "the Bible of the animal rights movement." He has since published widely in every form of media, both mass and niche. He has published in the Carnegie Council's Journal of Ethics & International Affairs and has spoken here in the past. -

The Definition of Effective Altruism

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 19/08/19, SPi 1 The Definition of Effective Altruism William MacAskill There are many problems in the world today. Over 750 million people live on less than $1.90 per day (at purchasing power parity).1 Around 6 million children die each year of easily preventable causes such as malaria, diarrhea, or pneumonia.2 Climate change is set to wreak environmental havoc and cost the economy tril- lions of dollars.3 A third of women worldwide have suffered from sexual or other physical violence in their lives.4 More than 3,000 nuclear warheads are in high-alert ready-to-launch status around the globe.5 Bacteria are becoming antibiotic- resistant.6 Partisanship is increasing, and democracy may be in decline.7 Given that the world has so many problems, and that these problems are so severe, surely we have a responsibility to do something about them. But what? There are countless problems that we could be addressing, and many different ways of addressing each of those problems. Moreover, our resources are scarce, so as individuals and even as a globe we can’t solve all these problems at once. So we must make decisions about how to allocate the resources we have. But on what basis should we make such decisions? The effective altruism movement has pioneered one approach. Those in this movement try to figure out, of all the different uses of our resources, which uses will do the most good, impartially considered. This movement is gathering con- siderable steam. There are now thousands of people around the world who have chosen -

Business Insider Article

11/11/2018 The world's best charity can save a life for $3,337.06 - Business Insider The world's best charity can save a life for $3,337.06 Chris Weller Jul. 29, 2015, 12:40 PM This isn't a melodramatic TV commercial: For $3,340, you can save a life right now. That's how much it costs to save one life if you donate to the Against Malaria Foundation Spencer Platt/Getty Images (AMF), the top charity in the world— as judged by GiveWell, a non-profit charity evaluator and advocate for effective altruism. While other charity evaluators tend only to look at where money is going, GiveWell's research seeks to understand how much gets there, who needs it most, and, perhaps most important, what that money can do. AMF rises above the rest. In the developed world, mosquitoes are pesky insects. But in underdeveloped countries in Africa, mosquitoes carry a raft of diseases. Easily the most deadly of those is malaria, which is responsible for approximately 600,000 deaths annually. Rather than invest millions in finding a vaccine, AMF tries to avoid infection through insecticide-treated bed nets, which have loads of research behind them supporting their effectiveness. GiveWell has three major requirements when selecting its top charities, and AMF fulfills all of them. The solution is proven to work, it successfully passes a vetting process (in this case, figuring out if AMF makes good on delivering the bed nets to people in need), and it's underfunded, which means there is a real need for outside donation. -

The Life You Can Save Acting Now to End World Poverty

The Life You Can Save: Acting Now to End World Poverty http://www.cceia.org/resources/transcripts/0134.html/:pf_printable? The Life You Can Save: Acting Now to End World Poverty Peter Singer , Joanne J. Myers March 18, 2009 Introduction Remarks Questions and Answers Introduction JOANNE MYERS: Good morning. I'm Joanne Myers, Director of Public Affairs Programs, and on behalf of the Carnegie Council I'd like to thank you for joining us. Our speaker, Peter Singer, has been described as one of the most innovative, provocative, and prolific philosophers living today. And, even though he was born and raised in Australia, he is perhaps America's most famous specialist in The Life You Can Save: Acting applied and practical ethics. Now to End World Poverty The topic of this presentation is poverty, and it is based on the 2007 Uehiro Lecture in Practical Ethics that he delivered at Oxford University. This talk was the catalyst for his book, The Life You Can Save: Acting Now to End World Poverty, and represents Professor Singer's efforts to distill his thoughts about why we give—or don't give—and what we should do about it. Ethics is about the basic choices we make and speaks to the challenges of what it means to live an ethical life. It is often defined as a good, a right, or a duty, and is considered in terms of the effects it has on the greatest number of people. Therefore, when one speaks about the moral obligation to eliminate global poverty, it is self-evident that the question of how we should approach this issue would arise. -

An Evaluation of the Theory of Animal Right in Peter Singer

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 9, Issue 9, September-2018 1394 ISSN 2229-5518 AN EVALUATION OF THE THEORY OF ANIMAL RIGHT IN PETER SINGER CHUKWUMA, JOSEPH NNAEMEKA And ELECHINGWUTA KINGSLEY OKECHUKWU ABSTRACT It is glaring that non-human animal have been exploited and annihilated in numerous ways by humans. This is a grave injustice that requires urgent retention and response, so as to protect animal rights and interest from oblivious mind. There are theories in the animal rights literature which have existed for some time now. Some against the protection of animal rights while some for the protection of animal rights. In line with the argument for the protection of animal rights, Peter singer an advocate for animal right protection argues in his book “Animal Liberation” that human should give equal consideration to the interest of animals when making decision to other species. He argued that the interests of every living being are the same. This work aims at examining and assessing the theory of animal rights in Peter singers. It sets out to clarify the absurdity that lovers around the protection of animal rights. This work adopts the philosophical method of analysis and evaluation. It exposes the historical origin of animal rights before the advent of Peter singer and even after him, Thereby using his thought to proffer possible end to the imminent sufferings caused by humans and animals. The only real way to protect animals is to assign them universal right under the theoretical concept of justice- observing animals right seriously means that by virtue of their existence (selfhood) and sentience they possess these right. -

Evidence Action

Evidence Action Evidence Action operates three main initiatives. Dispensers for Safe Water installs and maintains chlorine dispensers in rural Africa. The Deworm the World Initiative partners with governments in India, Nigeria, and Pakistan school-based deworming programs. And Evidence Action’s Accelerator drives new program development, testing and refining high-potential, cost-effective interventions. United States (USD) Donate to Evidence Acon Please select your country & currency. Donations are tax-deductible in the country selected. Launched Operating in 4M 275M 2013 6 people can access safe water children annually treated for countries worms Other ways to donate We recommend that gifts up to $1,000 be made online by credit card. If you are giving more than $1,000, please consider one of these alternatives. Check Bank Transfer Donor Advised Fund Cryptocurrencies Stocks or Shares Bequests Corporate matching program The problem: scaling impactful interventions In order to tackle extreme poverty at the level it exists, how do we bridge the gap between identifying evidence-based, cost-effective interventions that work and successfully scaling them up to improve the lives of millions? The solution: expertise Evidence Action’s mission is to be a world leader in scaling evidence-based and cost-effective programs to reduce the burden of poverty. Evidence Action works to identify and scale interventions in Africa and Asia, filling the gap between promising research and achieving measurable impact. Evidence Action was incubated by Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA), a highly respected poverty research network. (IPA is another of The Life You Can Save’s recommended organizations). How Evidence Action works Evidence Action operates three initiatives: Dispensers for Safe Water, Deworm the World Initiative, and Evidence Action’s Accelerator. -

Singer Famine Fall 2017

Famine, Affluence, and Morality Peter Singer Peter Singer: (1946 - ) uProf. at Princeton and Univ. of Melbourne uAuthor of Animal Liberation, 1st major work on “animal rights” uApplies utilitarian principles to current moral issues uArgues that rich societies are morally obligated to “Famine, Affluence, help poorer ones. and Morality” uThe Life You Can Save most recent book Utilitarianism: UTILITARIANISM --a.k.a.-- The Greatest Happiness Principle “...actions are right in proportion as they tend to produce happiness, wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness. By happiness is intended pleasure and the absence of pain....” Utilitarianism: Costs and Benefits • Utilitarianism seems to have problems accounting for our moral beliefs about “justice” and “individual rights.” • Yet, it seems to capture at least some of our “moral intuitions.” • And it seems that sometimes consideration of “maximizing overall happiness” may outweigh considerations of justice or individual rights. – What if helping others—that I didn’t harm—requires sacrificing my happiness? How much do I “owe?” Human Tragedy: “As I write this ... • “… people are dying in [fill in the blank] from lack of food, shelter, and medical care. The suffering and death that are occurring there are not inevitable, not unavoidable in any fatalistic sense of the term. Constant poverty, a [fill in the blank], and a [fill in the blank] have turned [many] million people into destitute refugees; nevertheless, it is not beyond the capacity of richer nations …. to reduce further suffering to very small proportions.” Singer: This is Morally Wrong • “…the way [we typically] react to [such] situations … cannot be justified…” • Singer believes we are (individually, and collectively) morally obligated to help people who live in poverty. -

Effective Altruism: How Big Should the Tent Be? Amy Berg – Rhode Island College Forthcoming in Public Affairs Quarterly, 2018

Effective Altruism: How Big Should the Tent Be? Amy Berg – Rhode Island College forthcoming in Public Affairs Quarterly, 2018 The effective altruism movement (EA) is one of the most influential philosophically savvy movements to emerge in recent years. Effective Altruism has historically been dedicated to finding out what charitable giving is the most overall-effective, that is, the most effective at promoting or maximizing the impartial good. But some members of EA want the movement to be more inclusive, allowing its members to give in the way that most effectively promotes their values, even when doing so isn’t overall- effective. When we examine what it means to give according to one’s values, I argue, we will see that this is both inconsistent with what EA is like now and inconsistent with its central philosophical commitment to an objective standard that can be used to critically analyze one’s giving. While EA is not merely synonymous with act utilitarianism, it cannot be much more inclusive than it is right now. Introduction The effective altruism movement (EA) is one of the most influential philosophically savvy movements to emerge in recent years. Members of the movement, who often refer to themselves as EAs, have done a great deal to get philosophers and the general public to think about how much they can do to help others. But EA is at something of a crossroads. As it grows beyond its beginnings at Oxford and in the work of Peter Singer, its members must decide what kind of movement they want to have. -

Review Essay of Peter Singer, the Life You Can Save

Bioethical Inquiry (2009) 6:239–247 DOI 10.1007/s11673-009-9159-0 Responding to Global Poverty: Review Essay of Peter Singer, The Life you can Save Christian Barry & Gerhard Øverland Received: 5 April 2009 /Accepted: 13 April 2009 /Published online: 26 May 2009 # Springer Science + Business Media B.V. 2009 Most affluent people are at least partially aware of the their economic policies toward poorer countries in great magnitude of world poverty. A great many of ways that might benefit them. the affluent believe that the lives of all people Why do the affluent do so little, and demand so everywhere are of equal fundamental worth when little of their governments, while remaining confident viewed impartially. In some contexts, at least, they that they are morally decent people who generally will also assert that people ought to prevent serious fulfil their duties to others? Are affluent people and suffering when they can do so, even at significant cost the governments that represent them actually fulfill- to themselves. But these same people contribute little ing their duties to the global poor, despite appearances or nothing to relief efforts or development initiatives, to the contrary? What kinds of changes in the and do not actively pressure their governments to alter behaviour of affluent people and their governments could bring about substantial improvements in the lives of the global poor? (Singer 2009) Christian Barry, Senior Research Fellow, Centre The life you can save is Peter Singer’s first book for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics, (Australian National University) and Gerhard Øverland , Senior Research Fellow, that focuses exclusively on these questions, and his Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics (University of most comprehensive engagement with critics of his Melbourne).