Comparing Two Descriptions of Earth Interior Structure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of a Heterogeneous Martian Mantle: Clues from K, P, Ti, Cr, and Ni Variations in Gusev Basalts and Shergottite Meteorites

Earth and Planetary Science Letters 296 (2010) 67–77 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth and Planetary Science Letters journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/epsl The evolution of a heterogeneous Martian mantle: Clues from K, P, Ti, Cr, and Ni variations in Gusev basalts and shergottite meteorites Mariek E. Schmidt a,⁎, Timothy J. McCoy b a Dept. of Earth Sciences, Brock University, St. Catharines, ON, Canada L2S 3A1 b Dept. of Mineral Sciences, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560-0119, USA article info abstract Article history: Martian basalts represent samples of the interior of the planet, and their composition reflects their source at Received 10 December 2009 the time of extraction as well as later igneous processes that affected them. To better understand the Received in revised form 16 April 2010 composition and evolution of Mars, we compare whole rock compositions of basaltic shergottitic meteorites Accepted 21 April 2010 and basaltic lavas examined by the Spirit Mars Exploration Rover in Gusev Crater. Concentrations range from Available online 2 June 2010 K-poor (as low as 0.02 wt.% K2O) in the shergottites to K-rich (up to 1.2 wt.% K2O) in basalts from the Editor: R.W. Carlson Columbia Hills (CH) of Gusev Crater; the Adirondack basalts from the Gusev Plains have more intermediate concentrations of K2O (0.16 wt.% to below detection limit). The compositional dataset for the Gusev basalts is Keywords: more limited than for the shergottites, but it includes the minor elements K, P, Ti, Cr, and Ni, whose behavior Mars igneous processes during mantle melting varies from very incompatible (prefers melt) to very compatible (remains in the shergottites residuum). -

Thermal and Crustal Evolution of Mars Steven A

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 107, NO. E7, 10.1029/2001JE001801, 2002 Thermal and crustal evolution of Mars Steven A. Hauck II1 and Roger J. Phillips McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences and Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Washington University, Saint Louis, Missouri, USA Received 11 October 2001; revised 4 February 2002; accepted 11 February 2002; published 16 July 2002. [1] We present a coupled thermal-magmatic model for the evolution of Mars’ mantle and crust that may be consistent with estimates of the average crustal thickness and crustal growth rate. By coupling a simple parameterized model of mantle convection to a batch- melting model for peridotite, we can investigate potential conditions and evolutionary paths of the crust and mantle in a coupled thermal-magmatic system. On the basis of recent geophysical and geochemical studies, we constrain our models to have average crustal thicknesses between 50 and 100 km that were mostly formed by 4 Ga. Our nominal model is an attempt to satisfy these constraints with a relatively simple set of conditions. Key elements of this model are the inclusion of the energetics of melting, a wet (weak) mantle rheology, self-consistent fractionation of heat-producing elements to the crust, and a near- chondritic abundance of those elements. The latent heat of melting mantle material is a small (percent level) contributor to the total planetary energy budget over 4.5 Gyr but is crucial for constraining the thermal and magmatic history of Mars. Our nominal model predicts an average crustal thickness of 62 km that was 73% emplaced by 4 Ga. -

Ocean Basin Bathymetry & Plate Tectonics

13 September 2018 MAR 110 HW- 3: - OP & PT 1 Homework #3 Ocean Basin Bathymetry & Plate Tectonics 3-1. THE OCEAN BASIN The world’s oceans cover 72% of the Earth’s surface. The bathymetry (depth distribution) of the interconnected ocean basins has been sculpted by the process known as plate tectonics. For example, the bathymetric profile (or cross-section) of the North Atlantic Ocean basin in Figure 3- 1 has many features of a typical ocean basins which is bordered by a continental margin at the ocean’s edge. Starting at the coast, there is a slight deepening of the sea floor as we cross the continental shelf. At the shelf break, the sea floor plunges more steeply down the continental slope; which transitions into the less steep continental rise; which itself transitions into the relatively flat abyssal plain. The continental shelf is the seaward edge of the continent - extending from the beach to the shelf break, with typical depths ranging from 130 m to 200 m. The seafloor of the continental shelf is gently sloping with undulating surfaces - sometimes interrupted by hills and valleys (see Figure 3- 2). Sediments - derived from the weathering of the continental mountain rocks - are delivered by rivers to the continental shelf and beyond. Over wide continental shelves, the sea floor slopes are 1° to 2°, which is virtually flat. Over narrower continental shelves, the sea floor slopes are somewhat steeper. The continental slope connects the continental shelf to the deep ocean with typical depths of 2 to 3 km. While the bottom slope of a typical continental slope region appears steep in the 13 September 2018 MAR 110 HW- 3: - OP & PT 2 vertically-exaggerated valleys pictured (see Figure 3-2), they are typically quite gentle with modest angles of only 4° to 6°. -

D6 Lithosphere, Asthenosphere, Mesosphere

200 Chapter d FAMILIAR WORLD The Present is the Key to the Past: HUGH RANCE d6 Lithosphere, asthenosphere, mesosphere < plastic zone > The terms lithosphere and asthenosphere stem from Joseph Barell’s 1914-15 papers on isostasy, entitled The Strength of the Earth's Crust, in the Journal of Geology.1 In the 1960s, seismic studies revealed a zone of rock weakness worldwide near the top of the upper part of the mantle. This zone of weakness is called the asthenosphere (Gk. asthenes, weak). The asthenosphere turned out to be of revolutionary significance for historical geology (see Topic d7, plate tectonic theory). Within the asthenosphere, rock behaves plastically at rates of deformation measured in cm/yr over lineal distances of thousands of kilometers. Above the asthenosphere, at the same rate of deformation, rock behaves elastically and, being brittle, it can break (fault). The shell of rock above the asthenosphere is called the lithosphere (Gk. lithos, stone). The lithosphere as its name implies is more rigid than the asthenosphere. It is important to remember that the names crust and lithosphere are not synonyms. The crust, the upper part of the lithosphere, is continental rock (granitic) in some places and is oceanic rock (basaltic) elsewhere. The lower part of lithosphere is mantle rock (peridotite); cooler but of like composition to the asthenosphere. The asthenosphere’s top (Figure d6.1) has an average depth of 95 km worldwide below 70+ million year old oceanic lithosphere.2 It shallows below oceanic rises to near seafloor at oceanic ridge crests. The rigidity difference between the lithosphere and the asthenosphere exists because downward through the asthenosphere, the weakening effect of increasing temperature exceeds the strengthening effect of increasing pressure. -

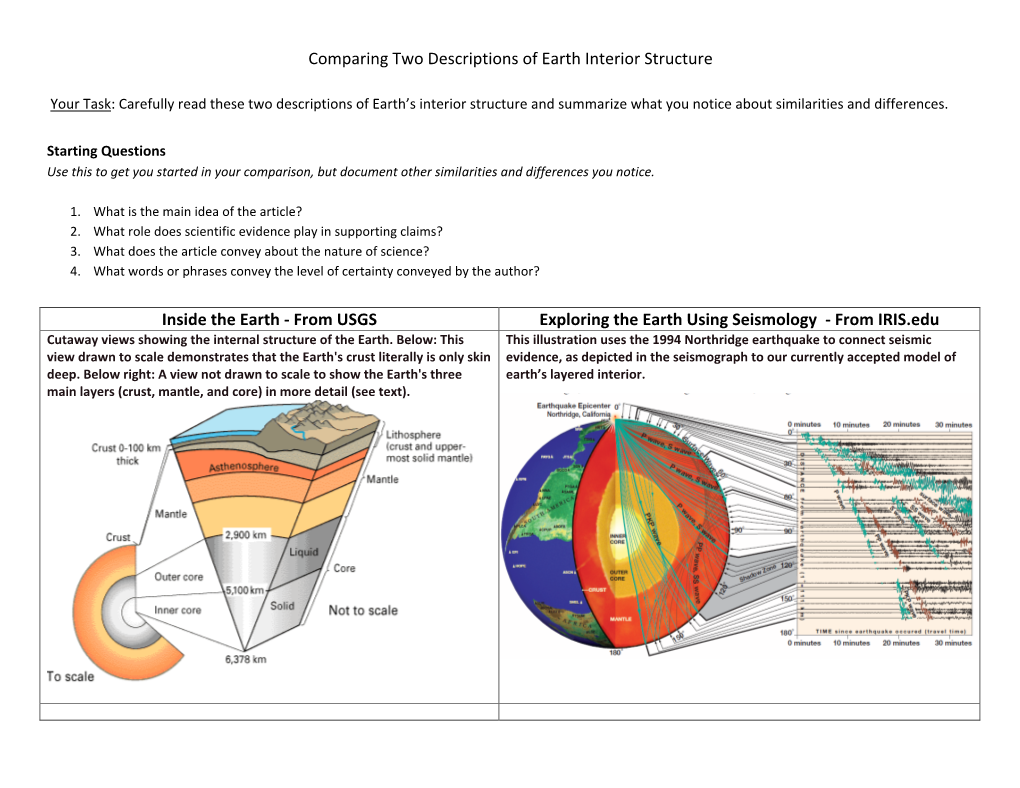

INTERIOR of the EARTH / an El/EMEI^TARY Xdescrrpntion

N \ N I 1i/ / ' /' \ \ 1/ / / s v N N I ' / ' f , / X GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 532 / N X \ i INTERIOR OF THE EARTH / AN El/EMEI^TARY xDESCRrPNTION The Interior of the Earth An Elementary Description By Eugene C. Robertson GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 532 Washington 1966 United States Department of the Interior CECIL D. ANDRUS, Secretary Geological Survey H. William Menard, Director First printing 1966 Second printing 1967 Third printing 1969 Fourth printing 1970 Fifth printing 1972 Sixth printing 1976 Seventh printing 1980 Free on application to Branch of Distribution, U.S. Geological Survey 1200 South Eads Street, Arlington, VA 22202 CONTENTS Page Abstract ......................................................... 1 Introduction ..................................................... 1 Surface observations .............................................. 1 Openings underground in various rocks .......................... 2 Diamond pipes and salt domes .................................. 3 The crust ............................................... f ........ 4 Earthquakes and the earth's crust ............................... 4 Oceanic and continental crust .................................. 5 The mantle ...................................................... 7 The core ......................................................... 8 Earth and moon .................................................. 9 Questions and answers ............................................. 9 Suggested reading ................................................ 10 ILLUSTRATIONS -

The Earth's Crust Is Like the Skin of an Apple

The Earth’s Crust Weathering & Erosion ! " Soil begins with rocks – so how is rock turned into soil? ! " How does soil travel and move? ! " Without sediments our planet would decline, perhaps ceasing to exist Inside the Earth The Earth's Crust is like the skin of an apple. It is very thin in comparison to the other three layers. The crust is only about 3-5 miles (8 kilometers) thick under the oceans(oceanic crust) and about 25 miles (32 kilometers) thick under the continents (continental crust). The temperatures of the crust vary from air temperature on top to about 1600 degrees Fahrenheit (870 degrees Celcius) in the deepest parts of the crust Three Laws of Thermodynamics ! " The first law of thermodynamics, also called conservation of energy, states that the total amount of energy in the universe is constant. This means that all of the energy has to end up somewhere, either in the original form or in a different from. We can use this knowledge to determine the amount of energy in a system, the amount lost as waste heat, and the efficiency of the system. ! " The second law of thermodynamics states that the disorder in the universe always increases. After cleaning your room, it always has a tendency to become messy again. This is a result of the second law. As the disorder in the universe increases, the energy is transformed into less usable forms. Thus, the efficiency of any process will always be less than 100%. ! " The third law of thermodynamics tells us that all molecular movement stops at a temperature we call absolute zero, or 0 Kelvin (-273oC). -

Asthenosphere–Lithospheric Mantle Interaction in an Extensional Regime

Chemical Geology 233 (2006) 309–327 www.elsevier.com/locate/chemgeo Asthenosphere–lithospheric mantle interaction in an extensional regime: Implication from the geochemistry of Cenozoic basalts from Taihang Mountains, North China Craton ⁎ Yan-Jie Tang , Hong-Fu Zhang, Ji-Feng Ying State Key Laboratory of Lithospheric Evolution, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, P.O. Box 9825, Beijing 100029, PR China Received 25 July 2005; received in revised form 27 March 2006; accepted 30 March 2006 Abstract Compositions of Cenozoic basalts from the Fansi (26.3–24.3 Ma), Xiyang–Pingding (7.9–7.3 Ma) and Zuoquan (∼5.6 Ma) volcanic fields in the Taihang Mountains provide insight into the nature of their mantle sources and evidence for asthenosphere– lithospheric mantle interaction beneath the North China Craton. These basalts are mainly alkaline (SiO2 =44–50 wt.%, Na2O+ K2O=3.9–6.0 wt.%) and have OIB-like characteristics, as shown in trace element distribution patterns, incompatible elemental (Ba/Nb=6–22, La/Nb=0.5–1.0, Ce/Pb=15–30, Nb/U=29–50) and isotopic ratios (87Sr/86Sr=0.7038–0.7054, 143Nd/ 144 Nd=0.5124–0.5129). Based on TiO2 contents, the Fansi lavas can be classified into two groups: high-Ti and low-Ti. The Fansi high-Ti and Xiyang–Pingding basalts were dominantly derived from an asthenospheric source, while the Zuoquan and Fansi low-Ti basalts show isotopic imprints (higher 87Sr/86Sr and lower 143Nd/144Nd ratios) compatible with some contributions of sub- continental lithospheric mantle. The variation in geochemical compositions of these basalts resulted from the low degree partial melting of asthenosphere and the interaction of asthenosphere-derived magma with old heterogeneous lithospheric mantle in an extensional regime, possibly related to the far effect of the India–Eurasia collision. -

Tectonics and Crustal Evolution

Tectonics and crustal evolution Chris J. Hawkesworth, Department of Earth Sciences, University peaks and troughs of ages. Much of it has focused discussion on of Bristol, Wills Memorial Building, Queens Road, Bristol BS8 1RJ, the extent to which the generation and evolution of Earth’s crust is UK; and Department of Earth Sciences, University of St. Andrews, driven by deep-seated processes, such as mantle plumes, or is North Street, St. Andrews KY16 9AL, UK, c.j.hawkesworth@bristol primarily in response to plate tectonic processes that dominate at .ac.uk; Peter A. Cawood, Department of Earth Sciences, University relatively shallow levels. of St. Andrews, North Street, St. Andrews KY16 9AL, UK; and Bruno The cyclical nature of the geological record has been recog- Dhuime, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Wills nized since James Hutton noted in the eighteenth century that Memorial Building, Queens Road, Bristol BS8 1RJ, UK even the oldest rocks are made up of “materials furnished from the ruins of former continents” (Hutton, 1785). The history of ABSTRACT the continental crust, at least since the end of the Archean, is marked by geological cycles that on different scales include those The continental crust is the archive of Earth’s history. Its rock shaped by individual mountain building events, and by the units record events that are heterogeneous in time with distinctive cyclic development and dispersal of supercontinents in response peaks and troughs of ages for igneous crystallization, metamor- to plate tectonics (Nance et al., 2014, and references therein). phism, continental margins, and mineralization. This temporal Successive cycles may have different features, reflecting in part distribution is argued largely to reflect the different preservation the cooling of the earth and the changing nature of the litho- potential of rocks generated in different tectonic settings, rather sphere. -

Seismic Velocity Structure of the Continental Lithosphere from Controlled Source Data

Seismic Velocity Structure of the Continental Lithosphere from Controlled Source Data Walter D. Mooney US Geological Survey, Menlo Park, CA, USA Claus Prodehl University of Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe, Germany Nina I. Pavlenkova RAS Institute of the Physics of the Earth, Moscow, Russia 1. Introduction Year Authors Areas covered J/A/B a The purpose of this chapter is to provide a summary of the seismic velocity structure of the continental lithosphere, 1971 Heacock N-America B 1973 Meissner World J i.e., the crust and uppermost mantle. We define the crust as 1973 Mueller World B the outer layer of the Earth that is separated from the under- 1975 Makris E-Africa, Iceland A lying mantle by the Mohorovi6i6 discontinuity (Moho). We 1977 Bamford and Prodehl Europe, N-America J adopted the usual convention of defining the seismic Moho 1977 Heacock Europe, N-America B as the level in the Earth where the seismic compressional- 1977 Mueller Europe, N-America A 1977 Prodehl Europe, N-America A wave (P-wave) velocity increases rapidly or gradually to 1978 Mueller World A a value greater than or equal to 7.6 km sec -1 (Steinhart, 1967), 1980 Zverev and Kosminskaya Europe, Asia B defined in the data by the so-called "Pn" phase (P-normal). 1982 Soller et al. World J Here we use the term uppermost mantle to refer to the 50- 1984 Prodehl World A 200+ km thick lithospheric mantle that forms the root of the 1986 Meissner Continents B 1987 Orcutt Oceans J continents and that is attached to the crust (i.e., moves with the 1989 Mooney and Braile N-America A continental plates). -

Essentials of Geology

INSTRUCTOR’S MANUAL AND TEST BANK Essentials of Geology Fourth Edition Stephen Marshak Instructor’s Manual by John Werner SEMINOLE STATE COLLEGE OF FLORIDA Test Bank by Jacalyn Gorczynski TEXAS A&M UNIVERSITY– CORPUS CHRISTI Heather L. Lehto ANGELO STATE UNIVERSITY Daniel Wynne SACRAMENTO COMMUNITY COLLEGE B W • W • NORTON & COMPANY • NEW YORK • LONDON —-1 —0 —+1 5577-50734_ch00_2P.indd77-50734_ch00_2P.indd iiiiii 110/5/120/5/12 55:41:41 PPMM W. W. Norton & Company has been in de pen dent since its founding in 1923, when William Warder Norton and Mary D. Herter Norton fi rst published lectures delivered at the People’s Institute, the adult education division of New York City’s Cooper Union. The Nortons soon expanded their program beyond the Institute, publishing books by celebrated academics from America and abroad. By mid- century, the two major pillars of Norton’s publishing program— trade books and college texts— were fi rmly established. In the 1950s, the Norton family transferred control of the company to its employees, and today— with a staff of four hundred and a comparable number of trade, college, and professional titles published each year— W. W. Norton & Company stands as the largest and oldest publishing house owned wholly by its employees. Copyright © 2013, 2009, 2007, 2004 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Associate Editor, Supplements: Callinda Taylor. Project Editor: Thom Foley. Production Manager: Benjamin Reynolds. Editorial Assistant, Supplements: Paula Iborra. Composition and project management: Westchester Publishing Ser vices. Art by CodeMantra and Precision Graphics. -

Controls of Subduction Geometry, Location of Magmatic Arcs, and Tectonics of Arc and Back-Arc Regions

Controls of subduction geometry, location of magmatic arcs, and tectonics of arc and back-arc regions TIMOTHY A. CROSS Exxon Production Research Company, P.O. Box 2189, Houston, Texas 77001 REX H. PILGER, JR. Department of Geology, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70803 ABSTRACT States), intra-arc extension (for example, convergence rate, direction and rate of the Basin and Range province), foreland absolute upper-plate motion, age of the de- Most variation in geometry and angle of fold and thrust belts, and Laramide-style scending plate, and subduction of aseismic inclination of subducted oceanic lithosphere tectonics. ridges, oceanic plateaus, or intraplate is caused by four interdependent factors. island-seamount chains. It is crucial to Combinations of (1) rapid absolute upper- INTRODUCTION recognize that, in the natural system of the plate motion toward the trench and active Earth, the major factors may interact and, overriding of the subducted plate, (2) rapid Since Luyendyk's (1970) pioneer attempt therefore, are interdependent variables. De- relative plate convergence, and (3) subduc- to relate subduction-zone geometry to some pending on the associations among them, in tion of intraplate island-seamount chains, fundamental aspect(s) of plate kinematics a historical and spatial context, their aseismic ridges, and oceanic plateaus and dynamics, subsequent investigations effects on the geometry of subducted litho- (anomalously low-density oceanic litho- have suggested an increasing variety and sphere can be additive, or by contrast, one sphere) cause low-angle subduction. Under complexity among possible controls and variable can act in opposition to another conditions of low-angle subduction, the resultant configurations of subduction variable and result in total or partial cancel- upper surface of the subducted plate is in zones. -

LESSON PLAN from Core to Crust Craters of the Moon National Monument & Preserve

LESSON PLAN From Core to Crust Craters of the Moon National Monument & Preserve Side view of mantle and crust GRADE LEVEL: Fifth Grade-Sixth Grade SUBJECT: Earth Science, Geology DURATION: 2-3 hours GROUP SIZE: Up to 36 (6-12 breakout groups) SETTING: classroom NATIONAL/STATE STANDARDS: CCRA.SL.1 NGSS.SEP.2 KEYWORDS: stratigraphy, earth science, geology Overview Students act out different parts of the Earth and then build models of the Earth showing its layers. (CLASSROOM ACTIVITY) Objective(s) Students will be able to name the parts of the Earth. Students will understand that the Earth is dynamic. Background The Earth, like the life on its surface, is changing all the time. Parts of it are molten and slowly rise, cool, and sink back toward the Earth's core, like soup simmering over a fire. Continents drift around the globe creating the features we think of when we think of geology. But most of the Earth lies unseen between our feet and the other side of the world. The Earth is made up of the crust, the mantle, and the core. Although geologists have only drilled a few miles into the Earth's crust, they have indirectly deduced much about the remainder of the planet's composition. The Crust What we walk on and see is the crust. It is wafer thin, only 3 to 22 miles thick. If the Earth were the size of a billiard ball, the crust would be as thick as a postage stamp stuck to its surface (think how thick the membrane of life would be that coats the Earth!).