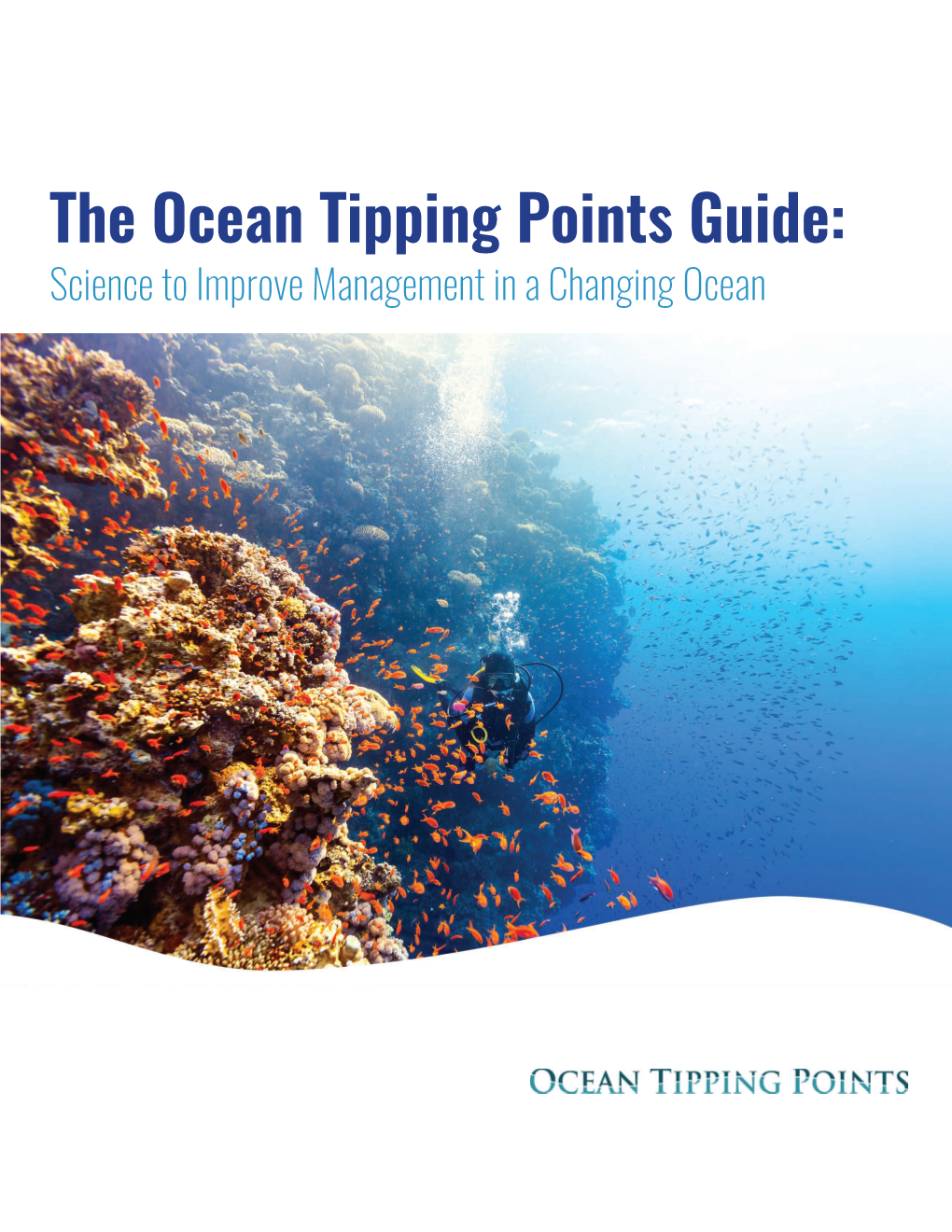

The Ocean Tipping Points Guide: Science to Improve Management in a Changing Ocean Ocean Tipping Points Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regime Shifts in the Anthropocene: Drivers, Risk, and Resilience

Supplementary Information for Regime Shifts in the Anthropocene: drivers, risk, and resilience by Juan-Carlos Rocha, Garry D. Peterson & Reinette O. Biggs. This document presents a worked example of a regime shift. We first provide a synthesis of the regime shift dynamics and a causal loop diagram (CLD). We then compare the resulting CLD with other regime shifts to make explicit the role of direct and indirect drivers. For each regime shift analyses in this study we did a similar literature synthesis and CLD which are available in the regime shift database. A longer version of this working example and CLDs can be found at www.regimeshifts.org. 1. Kelps transitions Summary. Kelp forests are marine coastal ecosystems located in shallow areas where large macroalgae ecologically engineer the environment to produce a coastal marine environmental substantially different from the same area without kelp. Kelp forests can undergo a regime shift to turf-forming algae or urchin barrens. These shift leads to loss of habitat and ecological complexity. Shifts to turf algae are related to nutrient input, while shifts to urchin barrens are related to trophic-level changes. The consequent loss of habitat complexity may affect commercially important fisheries. Managerial options include restoring biodiversity and installing wastewater treatment plants in coastal zones. Kelps are marine coastal ecosystems dominated by macroalgae typically found in temperate areas. This group of species form submarine forests with three or four layers, which provides different habitats to a variety of species. These forests maintain important industries like lobster and rockfish fisheries, the chemical industry with products to be used in e.g. -

Ecological Thresholds: the Key to Successful Environmental Management Or an Important Concept with No Practical Application?

Ecosystems (2006) 9: 1–13 DOI: 10.1007/s10021-003-0142-z MINI REVIEW Ecological Thresholds: The Key to Successful Environmental Management or an Important Concept with No Practical Application? Peter M. Groffman,1* Jill S. Baron,2 Tamara Blett,3 Arthur J. Gold,4 Iris Goodman,5 Lance H. Gunderson,6 Barbara M. Levinson,5 Margaret A. Palmer,7 Hans W. Paerl,8 Garry D. Peterson,9 N. LeRoy Poff,10 David W. Rejeski,11 James F. Reynolds,12 Monica G. Turner,13 Kathleen C. Weathers,1 and John Wiens14 1Institute of Ecosystem Studies, Box AB, Millbrook, New York 12545, USA; 2Natural Resource Ecology Laboratory, US Geological Survey, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado 80523-1499, USA; 3Air Resources Division, USDI-National Park Service, Academy Place, Room 450, P.O. Box 25287 Denver, Colorado 80225-0287, USA; 4Department of Natural Resources Science, 105 Coastal Institute in Kingston, University of Rhode Island, One Greenhouse Road, Kingston, Rhode Island 02881, USA 5US Environmental Protection Agency Headquarters, Ariel Rios Building, 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20460, USA; 6Department of Environmental Studies, Emory University, 400 Dowman Drive, Atlanta, Georgia 30322, USA; 7University of Maryland, Plant Sciences Building 4112, College Park, Maryland 20742-4415, USA; 8Institute of Marine Sciences, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 3431 Arendell Street, Morehead City, North Carolina 28557, USA; 9Center for Limnology, University of Wisconsin, 680 N. Park St., Madison, Wisconsin 53706, USA; 10Department of -

Environmental Limits Page 1

POST Report 370 January 2011 Living with Environmental Limits Page 1 Summary Human well-being is dependent upon assessment approaches. However, where renewable natural resources. Agricultural there is a risk of thresholds being systems, for example, depend upon plant breached and potentially irreversible productivity, soil, the water cycle, the impacts occurring, additional policy nitrogen, sulphur and phosphorus nutrient safeguards to maintain natural resource cycles and a stable climate. Renewable systems within environmental limits are natural resources can be subject to required. biological and physical thresholds beyond which irreversible changes in benefit Managing ecosystems to maximise one provision may occur. These are difficult to particular benefit, such as food provision, define and many are likely to be identified can result in declines in other benefits. only once crossed. An environmental limit The evidence base is not yet sufficient to is usually interpreted as the point or range determine the most effective ways to of conditions beyond which there is a maintain benefit provision within significant risk of thresholds being environmental limits, but a range of policy exceeded and unacceptable changes responses are seeking to optimise multiple occurring.1 benefit provision, including: Biodiversity loss, climate change and a agri-environment schemes range of other pressures are affecting generic measures to enhance renewable natural resources. If biodiversity, which may increase governments do not effectively monitor the the capacity of natural resource use and degradation of natural resource systems to adapt to environmental systems in national account frameworks, change the probability of costs arising from the use of ecological processes to exploiting natural resources beyond increase overall natural system environmental limits is not taken into resilience to address problems account. -

Konar, B., and J.A. Estes. 2003. the Stability of Boundary Regions

Ecology, 84(1), 2003, pp. 174±185 q 2003 by the Ecological Society of America THE STABILITY OF BOUNDARY REGIONS BETWEEN KELP BEDS AND DEFORESTED AREAS BRENDA KONAR1,2 AND JAMES A. ESTES1 1U.S. Geological Survey and Department of Biology, A-316 Earth and Marine Sciences Building, University of California, Santa Cruz, California 95064 USA Abstract. Two distinct organizational states of kelp forest communities, foliose algal assemblages and deforested barren areas, typically display sharp discontinuities. Mecha- nisms responsible for maintaining these state differences were studied by manipulating various features of their boundary regions. Urchins in the barren areas had signi®cantly smaller gonads than those in adjacent kelp stands, implying that food was a limiting resource for urchins in the barrens. The abundance of drift algae and living foliose algae varied abruptly across the boundary between kelp beds and barren areas. These observations raise the question of why urchins from barrens do not invade kelp stands to improve their ®tness. By manipulating kelp and urchin densities at boundary regions and within kelp beds, we tested the hypothesis that kelp stands inhibit invasion of urchins. Urchins that were ex- perimentally added to kelp beds persisted and reduced kelp abundance until winter storms either swept the urchins away or caused them to seek refuge within crevices. Urchins invaded kelp bed margins when foliose algae were removed but were prevented from doing so when kelps were replaced with physical models. The sweeping motion of kelps over the sea¯oor apparently inhibits urchins from crossing the boundary between kelp stands and barren areas, thus maintaining these alternate stable states. -

Physico-Chemical Thresholds in the Distribution of Fish Species Among

Knowl. Manag. Aquat. Ecosyst. 2017, 418, 41 Knowledge & © V. Roubeix et al., Published by EDP Sciences 2017 Management of Aquatic DOI: 10.1051/kmae/2017032 Ecosystems www.kmae-journal.org Journal fully supported by Onema RESEARCH PAPER Physico-chemical thresholds in the distribution of fish species among French lakes Vincent Roubeix1,*, Martin Daufresne1, Christine Argillier1, Julien Dublon1, Anthony Maire1,a, Delphine Nicolas1,b, Jean-Claude Raymond2,3 and Pierre-Alain Danis2 1 Irstea, UR RECOVER, Pôle AFB-Irstea hydroécologie plans d’eau, Centre d’Aix-en-Provence, 3275 route Cézanne, 13182 Aix-en-Provence, France 2 Agence française pour la biodiversité, Pôle AFB-Irstea hydroécologie plans d’eau, 13182 Aix-en-Provence, France 3 Agence française pour la biodiversité, Délégation Régionale Rhône-Alpes, Unité Spécialisée Milieux Lacustres, 74200 Thonon-les-Bains, France Abstract – The management of lakes requires the definition of physico-chemical thresholds to be used for ecosystem preservation or restoration. According to the European Water Framework Directive, the limits between physico-chemicalquality classes must be set consistently with biological quality elements. Onewayto do this consists in analyzing the response of aquatic communities to environmental gradients across monitoring sites and in identifying ecological community thresholds, i.e. zones in the gradients where the species turnover is the highest. In this study, fish data from 196 lakes in France were considered to derive ecological thresholds using the multivariate method of gradient forest. The analysis was performed on 25 species and 36 environmental parameters. The results revealed the highest importance of maximal water temperature in the distributionoffishspecies.Otherimportantparametersincludedgeographicalfactors,dissolvedorganiccarbon concentrationandwater transparency,whilenutrients appearedto have lowinfluence. -

Defining and Identifying Environmental Limits for Sustainable Development

Defining and Identifying Environmental Limits for Sustainable Development A Scoping Study Funded by Full Technical Report Project Team: Prof. Roy Haines-Young PD Dr. Marion Potschin Duncan Cheshire Centre for Environmental Management School of Geography, University of Nottingham Nottingham NG7 2RD [email protected] March 2006 Project Code NR0102 Defining and Identifying Environmental Limits for Sustainable Development: Final Report Citation: HAINES-YOUNG, R.; POTSCHIN, M. and D. CHESHIRE (2006): Defining and identifying Environmental Limits for Sustainable Development. A Scoping Study. Final Full Technical Report to Defra, 103 pp + appendix 77 pp, Project Code NR0102. Defining and Identifying Environmental Limits for Sustainable Development: Final Technical Report Contents Page Acknowledgements ii Executive Summary iv Part I Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Context and Aim 1 Part II: Conceptual Frameworks 4 Chapter 2: Limits and Thresholds: Definitions 4 Chapter 3: Identifying Limits and Thresholds 12 Chapter 4: Values and the Problem of Limits and Thresholds 29 Part III: Exploring the Evidence Base 33 Chapter 5: Biodiversity 33 Chapter 6: Land Use and Landscape 42 Chapter 7: Recreation 52 Chapter 8: Marine Environment 57 Chapter 9: Water - supply and demand 62 Chapter 10: Climate Change 68 Chapter 11: Pollution Loads 75 Part IV: Conclusions and Recommendations 82 Chapter 12: Respecting Environmental Limits 82 References 94 Appendix A: Briefing and Position Papers by external experts 104 i Defining and Identifying Environmental Limits for Sustainable Development: Final Technical Report Acknowledgements Part III of this report “Exploring the Evidence Base” draws heavily upon a set of position papers from invited scientists, which are presented in their original form in the appendix of this full technical report. -

Estimated Extent of Urchin Barrens on the East Coast of Northland, New Zealand

Estimated extent of urchin barrens on the east coast of Northland, New Zealand Vince Kerr and Roger Grace, October 2017 1 Estimated extent of urchin barrens on the east coast of Northland, New Zealand Vince Kerr and Roger Grace, October 2017 Cover Photo: An example of the urchin barren condition taken just south of the Cape Rodney to Okakari Point (Leigh) Marine Reserve at Cape Rodney, showing the greyish bare rock appearance of the urchin barren contrasted with the dark appearance in the aerial view of the algal forests. These photos also demonstrate the typical zonation of macroalgal forests and urchin barrens found in fished areas in northern New Zealand. Photo credit: Nick Shears Keywords: urchin barrens, marine habitat mapping, habitat classification, algal forest health, algal forest restoration, wave exposure, marine reserves, partially protected areas, Northland Citation: Kerr, V.C., Grace, R.V., 2017. Estimated extent of urchin barrens on shallow reefs of Northland’s east coast. A report prepared for Motiti Rohe Moana Trust. Kerr & Associates, Whangarei. Contact the authors: Vince Kerr, Kerr & Associates Phone +64 9 4351518, email: [email protected] Kerr & Associates web site 2 Contents Executive summary ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Client brief ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Background -

POTENTIAL IMPACTS of KELP FOREST HABITAT RESTORATION ALONG the PALOS VERDES PENINSULA Jeremy T

POTENTIAL IMPACTS OF KELP FOREST HABITAT RESTORATION ALONG THE PALOS VERDES PENINSULA Jeremy T. Claisse1, Jonathan P. Williams1, Laurel A. Zahn1, Daniel J. Pondella1 & Tom Ford2 1 Vantuna Research Group, Department of Biology, Occidental College, Los Angeles, CA 90041 2 The Bay Foundation, Los Angeles, CA 90045 Urchin barrens and kelp forest habitat Urchin barrens effect the invertebrate, kelp, benthic cover and fish communities restoration We sampled 25 sites in both 2012 and High densities of the unfished purple 2013 (Fig. 1) using a standardized Kelp Community giant kelp urchin (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus) comprehensive community monitoring southern result in ‘‘urchin barrens’’ largely survey protocol (for details see Hamilton et sea palm devoid of macroalgae across 61 ha of al. 2010 PNAS 107:18272-18277 and Claisse et rocky reef along the Palos Verdes al. 2012 PLoS ONE 7:e30290). Sites included Peninsula in southern California (Fig. 1; established kelp forests (green), extent of mapped urchin barrens shown urchin barrens (red) and those adjacent to urchin barrens (grey). We only in red). The study presented here is used data from the 5 m depth zone where most barrens occur. Species- focused on evaluating the potential specific site means were calculated by pooling data over both years. For effects of kelp forest habitat restoration fishes, estimated lengths were converted to weights using length-weight Fig. 4. nMDS plot of the kelp community using square by comparing the differences between relationships. root transformed density and a Bray-Curtis similarity ©Tom Boyd Images 2013 urchin barren and kelp forest habitats. matrix. Significant differences were found among site • We found significant community level differences among site categories (R adonis PERMANOVA: F2,16=8.5, categories in nMDS plots (Fig. -

Bull Kelp (Nereocystic Lutkeana) Restoration and Management in Northern California

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Projects and Capstones Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Spring 5-14-2020 Bull Kelp (Nereocystic lutkeana) Restoration and Management in Northern California Olivia Johnson [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone Part of the Marine Biology Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, Other Environmental Sciences Commons, Other Plant Sciences Commons, Sustainability Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Olivia, "Bull Kelp (Nereocystic lutkeana) Restoration and Management in Northern California" (2020). Master's Projects and Capstones. 1035. https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/1035 This Project/Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects and Capstones by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This Master’s Project Bull Kelp (Nereocystic lutkeana) Restoration and Management in Northern California by Olivia Johnson is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Science in Environmental Management at the University of San Francisco May 10, 2020 Submitted: Received: 5/10/2020 ________________________ Olivia Johnson Date Aviva Rossi Date Table of Contents 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………………..…….1 1.1. Objectives…..…………………………………………………………………………4 1.2. Background…..…………………………………………………………………..……4 1.2.1. Ecology and Geographic Distribution of Global Kelp Forests 1.2.2. -

Research to Develop and Manage the Sea Urchin Fisheries of NSW and Eastern Victoria

Research to develop and manage the sea urchin fisheries of NSW and eastern Victoria D.G. Worthington and C.Blount Cronulla Fisheries Centre, P.O. Box 21, Cronulla, NSW, 2230 Australia FRDC Project No. 1999/128 October 2003 NSW Fisheries Final Report Series No. 56 ISSN 1440-3544 Research to develop and manage the sea urchin fisheries of NSW and eastern Victoria D.G. Worthington and C.Blount Cronulla Fisheries Centre, P.O. Box 21, Cronulla, NSW, 2230 Australia FRDC Project No. 1999/128 October 2003 NSW Fisheries Final Report Series No. 56 ISSN 1440-3544 Research to develop and manage the sea urchin fisheries of NSW and eastern Victoria October 2003 Authors: D.G. Worthington and C.Blount Published By: NSW Fisheries Postal Address: PO Box 21, Cronulla NSW 2230 Internet: www.fisheries.nsw.gov.au NSW Fisheries This work is copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act (Cth), no part of this publication may be reproduced by any process, electronic or otherwise, without the specific written permission of the copyright owners. Neither may information be stored electronically in any form whatsoever without such permission. DISCLAIMER Every attempt has been made to provide accurate information in this document. However, no liability attaches to NSW Fisheries or to any organisation or individual concerned with the supply of information or the preparation of this document for any consequences of using the information contained in this document. ISSN 1440-3544 Contents i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................... -

Recreational Divers of Oregon Proposal for Kelp Forest Preservation in Rocky Subtidal Zones of the Oregon Coast

Initial Proposal Period Oregon Rocky Habitat Management Strategy FORMAL LETTER to O.P.A.C. Recreational Divers of Oregon Proposal for Kelp Forest Preservation in Rocky Subtidal Zones of the Oregon Coast @NBCNEWS: “With a loss of kelp forests, you're going to have a very, very profound impact on an ecosystem,” said Tristin McHugh, Reef Check California’s North coast regional manager. “It's like losing your redwoods. What would happen if you saw 90 percent of your redwoods drop dead right now?” For McHugh and many others, the biggest problem is awareness. Most people don’t even realize what sort of a catastrophe is happening below the sea surface. “This is the fight of our generation,” she said. “If we can't set ourselves up right now, there's going to be nothing for our kids further down the line." Initial Proposal Period Purple sea urchins predating the last kelp on this reef- completing an ‘urchin barren’ Special Note: In case the matching Proposal submitted 12/31/20 on the SeaSketch website may not meet some Rocky Shores’ Proposal screening criteria, (the ideas herein are really meant for most of the subtidal sites of the Oregon Coast) - we are also submitting this via email as a FORMAL LETTER to OPAC and the Rocky Shores Working Group. Pg. 37 Oregon Territorial Sea Plan: Part Three “Where the desired outcome cannot be met with a site designation proposal, members of the public and interested entities should outline their concern or desired regulatory change in a formal letter to the Ocean Policy Advisory Council.” Contact Information Please fill out the following section with primary contact information for this proposal. -

Influence of Salinity Gradient Changes on Phytoplankton Growth Caused

water Article Influence of Salinity Gradient Changes on Phytoplankton Growth Caused by Sluice Construction in Yongjiang River Estuary Area Menglin Yuan, Cuiling Jiang *, Xi Weng and Manxue Zhang College of Hydrology and Water Resources, Hohai University, Nanjing 210098, China; [email protected] (M.Y.); [email protected] (X.W.); [email protected] (M.Z.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 15 August 2020; Accepted: 2 September 2020; Published: 7 September 2020 Abstract: Though the number of sluices and dams in coastal areas has increased rapidly in recent years, the influence of their construction on phytoplankton in estuary areas is hardly known. This paper aims to provide a reference for quantitative research on the ecological influence of sluice construction and give ecological justifications for the setting of environmental standards in the estuary areas. The survey data gained at the lower reach of the Yongjiang River and its estuarine areas in June 2015 were used in MIKE21 software (Danish Hydraulic Institute (DHI), Denmark)) for establishing a two-dimensional numerical model to simulate the salinity field distribution after sluice construction. Based on the simulation results, the salinity gradient changes caused by the construction were analyzed. The one-dimensional Gaussian model was applied to calculated the phytoplankton’s ecological threshold interval over the salinity changes, which helped predict the influence of salinity changes on phytoplankton cell density. The study shows that salinity in the Yongjiang estuary increases obviously, beyond the phytoplankton ecological threshold, after sluice construction without water discharge. Salinity will become a restriction factor to phytoplankton growth after sluice construction in the study area, which may cause a sharp decrease of certain phytoplankton species.