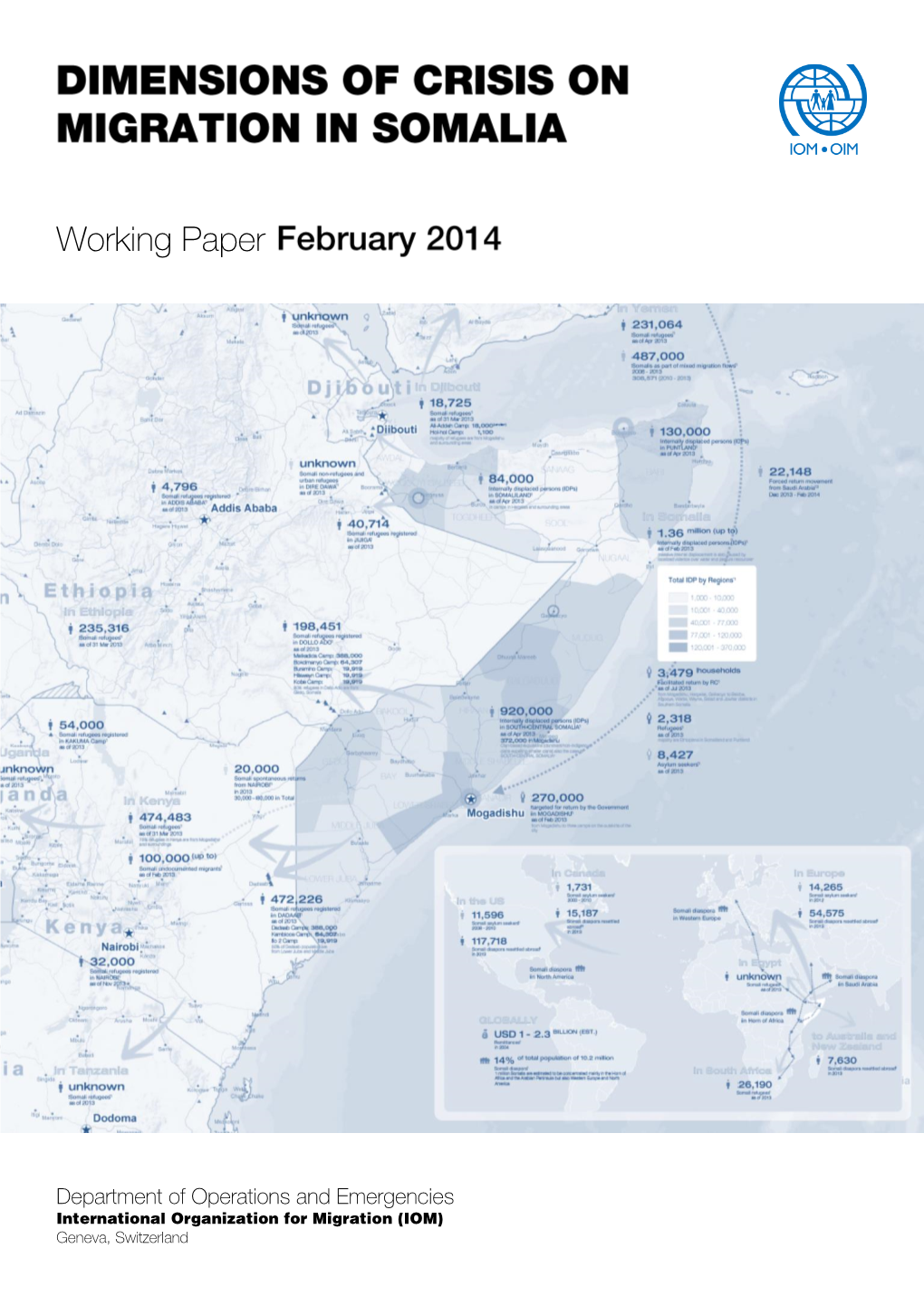

Dimensions of Crisis on Migration in Somalia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

Somalis in Europe

INTERACT – RESearcHING THIRD COUNTRY NatiONALS’ INTEGratiON AS A THREE-WAY PROCESS - IMMIGrantS, COUNTRIES OF EMIGratiON AND COUNTRIES OF IMMIGratiON AS ActORS OF INTEGratiON Somalis in Europe Monica Fagioli-Ndlovu INTERACT Research Report 2015/12 CEDEM INTERACT Researching Third Country Nationals’ Integration as a Three-way Process - Immigrants, Countries of Emigration and Countries of Immigration as Actors of Integration Research Report Country Report INTERACT RR 2015/12 Somalis in Europe Monica Fagioli-Ndlovu PhD candidate in Anthropology, The New School, New York This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. Requests should be addressed to [email protected] If cited or quoted, reference should be made as follows: Monica Fagioli-Ndlovu, Somalis in Europe, INTERACT RR 2015/12, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, San Domenico di Fiesole (FI): European University Institute, 2015. The opinions expressed are those of the author(s) only and should not be considered as representative of the official position of the European Commission or of the European University Institute. © 2015, European University Institute ISBN: 978-92-9084-292-7 doi:10.2870/99413 Catalogue Number: QM-04-15-339-EN-N European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy http://www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ http://interact-project.eu/publications/ http://cadmus.eui.eu INTERACT - Researching Third Country Nationals’ Integration as a Three-way Process - Immigrants, Countries of Emigration and Countries of Immigration as Actors of Integration In 2013 (Jan. -

Briefing Paper

NEW ISSUES IN REFUGEE RESEARCH Working Paper No. 65 Pastoral society and transnational refugees: population movements in Somaliland and eastern Ethiopia 1988 - 2000 Guido Ambroso UNHCR Brussels E-mail : [email protected] August 2002 Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees CP 2500, 1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.unhcr.org These working papers provide a means for UNHCR staff, consultants, interns and associates to publish the preliminary results of their research on refugee-related issues. The papers do not represent the official views of UNHCR. They are also available online under ‘publications’ at <www.unhcr.org>. ISSN 1020-7473 Introduction The classical definition of refugee contained in the 1951 Refugee Convention was ill- suited to the majority of African refugees, who started fleeing in large numbers in the 1960s and 1970s. These refugees were by and large not the victims of state persecution, but of civil wars and the collapse of law and order. Hence the 1969 OAU Refugee Convention expanded the definition of “refugee” to include these reasons for flight. Furthermore, the refugee-dissidents of the 1950s fled mainly as individuals or in small family groups and underwent individual refugee status determination: in-depth interviews to determine their eligibility to refugee status according to the criteria set out in the Convention. The mass refugee movements that took place in Africa made this approach impractical. As a result, refugee status was granted on a prima facie basis, that is with only a very summary interview or often simply with registration - in its most basic form just the name of the head of family and the family size.1 In the Somali context the implementation of this approach has proved problematic. -

Transnational Crimes Among Somali-Americans: Convergences of Radicalization and Trafficking

The author(s) shown below used Federal funding provided by the U.S. Department of Justice to prepare the following resource: Document Title: Transnational Crimes among Somali- Americans: Convergences of Radicalization and Trafficking Author(s): Stevan Weine, Edna Erez, Chloe Polutnik Document Number: 252135 Date Received: May 2019 Award Number: 2013-ZA-BX-0008 This resource has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. This resource is being made publically available through the Office of Justice Programs’ National Criminal Justice Reference Service. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Transnational Crimes among Somali-Americans: Convergences of Radicalization and Trafficking Stevan Weine, Edna Erez, and Chloe Polutnik 1 This resource was prepared by the author(s) using Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This project was supported by Award No. 2013-ZA-BX-0008, awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Justice. 2 This resource was prepared by the author(s) using Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Somalia's Missing Million: the Somali Diaspora and Its Role in Development

SOMALIA’S MISSING MILLION: THE SOMALI DIASPORA AND ITS ROLE IN DEVELOPMENT MARCH 2009 1 A report for UNDP by Hassan Sheikh and Sally Healy on the Role of the Diaspora in Somali Development. “The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of UNDP.” 2 Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 6 Locating the Somali Diaspora – in Search of the Missing Million ............................... 6 Waves of Migration......................................................................................................... 11 Some Characteristics of the Somali Diaspora .............................................................. 13 Political Engagement ...................................................................................................... 15 Economic Support to Somalia ....................................................................................... 18 Remittances ................................................................................................................... 18 Economic Recovery ...................................................................................................... 20 Humanitarian and Emergency Assistance .................................................................... 23 Development Assistance (Service Delivery) ................................................................ 25 Human Resources ........................................................................................................ -

Internal Migration, England and Wales: Year Ending June 2015

Statistical bulletin Internal migration, England and Wales: Year Ending June 2015 Residential moves between local authorities and regions in England and Wales, as well as moves to or from the rest of the UK (Scotland and Northern Ireland). Contact: Release date: Next release: Nicola J White 23 June 2016 June 2017 [email protected] +44 (0)1329 444647 Notice 22 June 2017 From mid-2016 Population Estimates and Internal Migration were combined in one Statistical Bulletin. Page 1 of 16 Table of contents 1. Main points 2. Things you need to know 3. Tell us what you think 4. Moves between local authorities in England and Wales 5. Cross-border moves 6. Characteristics of movers 7. Area 8. International comparisons 9. Where can I find more information? 10. References 11. Background notes Page 2 of 16 1 . Main points There were an estimated 2.85 million residents moving between local authorities in England and Wales between July 2014 and June 2015. This is the same level shown in the previous 12-month period. There were 53,200 moves from England and Wales to Northern Ireland and Scotland, compared with 45,600 from Northern Ireland and Scotland to England and Wales. This means there was a net internal migration loss for England and Wales of 7,600 people. For the total number of internal migration moves the sex ratio is fairly neutral; in the year to June 2015, 1.4 million (48%) of moves were males and 1.5 million (52%) were females. Young adults were most likely to move, with the biggest single peak (those aged 19) reflecting moves to start higher education. -

Migration and Religion in Scotland a Study on the Influence of Religion on Migration Behaviour

Migration and Religion in Scotland A study on the influence of religion on migration behaviour LSCS Research Working Paper 8.0 November 2010 Jasper van Dijck Radboud University Nijmegen Faculty of Social Science Peteke Feijten University of St Andrews Faculty of Geography and Geosciences Paul Boyle University of St Andrews Faculty of Geography and Geosciences Contents Abstract 1 Introduction 2 Theory and Background 2.1 Migration & religion 2.2 Secularization 2.3 The Scottish context 2.4 Data and Variables 2.5 Analysis 3. Conclusion and discussion 4. References 5. Appendix A. Frequencies and means for variables in migration analysis 6. Appendix B. Frequencies and means for variables in secularization analysis 2 Abstract This paper analyzes the influence of individual religion on internal migration in Scotland. Two aspects of religion are studied: denomination and secularization. Drawing on data from the Scottish Longitudinal Study, a 5.3% population sample linking the 1991 and 2001 censuses, this paper uses the location- specific capital theory to argue that religious individuals are less likely to migrate than non-religious individuals and that Catholics are less likely to migrate than Protestants. It also uses the modernization theory to argue that individuals who moved from a rural to an urban area are more likely to have become secular. The findings corroborate the hypotheses and thus confirm that individual religion is still an important factor in explaining contemporary internal migration. 1 Introduction Classic migration theory predicts that individuals will only move if they expect that the gains of a move will outweigh its costs (Brown & Moore 1970; De Jong & Fawcett 1981). -

Culture, Context and Mental Health of Somali Refugees

Culture, context and mental health of Somali refugees A primer for staff working in mental health and psychosocial support programmes I © UNHCR, 2016. All rights reserved Reproduction and dissemination for educational or other non- commercial purposes is authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes, or translation for any purpose, is prohibited without the written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to the Public Health Section of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) at [email protected] This document is commissioned by UNHCR and posted on the UNHCR website. However, the views expressed in this document are those of the authors and not necessarily those of UNHCR or other institutions that the authors serve. The editors and authors have taken all reasonable precautions to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either express or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees be liable for damages arising from its use. Suggested citation: Cavallera, V, Reggi, M., Abdi, S., Jinnah, Z., Kivelenge, J., Warsame, A.M., Yusuf, A.M., Ventevogel, P. (2016). Culture, context and mental health of Somali refugees: a primer for staff working in mental health and psychosocial support programmes. Geneva, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Cover photo: Dollo Ado, South East Ethiopia / Refugees are waiting for non-food items like plastic sheets and jerry cans. -

FBI054535 ~~N Diaspora Customs Traditions :··

ACLURM055018 FBI054535 US Somali Diaspora 8 Clan I0 Islamic Traditions II Flag . 12 Cultural Customs 16 Language ··13 .1ega[.Jssues .. :.... :"'. :·· .•... ;Appendix :,:·.\{ ... ~~N FBI054536 ACLURM055019 ~~ ~A~ History (U) 21 October. 1969: Corruption and a power vacuum in the Somali government Somalia, located at the Horn of Africa (U) culminate in a bloodless coup led by Major near the Arabian Peninsula, has been a General Muhammad Siad Barre. crossroads of civilization for thousands of years. Somalia played an important role in (U) 1969-1991: Siad Barre establishes the commerce of ancient Egyptians, and with a military dictatorship that divides and later Chinese, Greek, and Arab traders. oppresses Somalis. (U) 18th century: Somalis develop a (U) 27 January J99J: Siad Barre flees culture shaped by pastoral nomadism and Mogadishu, and the Somali state collapses~ adherence to Islam. Armed dan-based militias fight for power. (U) 1891-1960: European powers create (U) 1991-199S:The United Nations five separate Somali entities: Operation in Somalia (UNISOM) I and II- initially a US-led, UN-sanctioned multilateral » British Somaliland (north central). intervention-attempts to resolve the » French Somaliland (east and southeast). civil war and provide humanitarian aid. » Italian Somaliland (south). The ambitious UNISOM mandate to rebuild » Ethiopian Somaliland (the Ogaden). a Somali government threatens warlords' >> The Northern Frontier District (NFD) interests and fighting ensues. UN forces of Kenya. depart in 1995, leaving Somalia in a state (U) ., 960: Italian and British colonies of violence and anarchy. Nearly I million merge into the independent Somali Republic. refugees and almost 5 million people risk starvation and disease. Emigration rises (U} 1960-1969: Somalia remains sharply. -

The Path of Somali Refugees Into Exile Exile Into Refugees Somali of Path the Joëlle Moret, Simone Baglioni, Denise Efionayi-Mäder

The Path of Somalis have been leaving their country for the last fifteen years, fleeing civil war, difficult economic conditions, drought and famine, and now constitute one of the largest diasporas in the world. Somali Refugees into Exile A Comparative Analysis of Secondary Movements Organized in the framework of collaboration between UNHCR and and Policy Responses different countries, this research focuses on the secondary movements of Somali refugees. It was carried out as a multi-sited project in the following countries: Djibouti, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, the Netherlands, Efionayi-Mäder Denise Baglioni, Simone Moret, Joëlle South Africa, Switzerland and Yemen. The report provides a detailed insight into the movements of Somali refugees that is, their trajectories, the different stages in their migra- tion history and their underlying motivations. It also gives a compara- tive overview of different protection regimes and practices. Authors: Joëlle Moret is a social anthropologist and scientific collaborator at the SFM. Simone Baglioni is a political scientist and scientific collaborator at the SFM and at the University Bocconi in Italy. Denise Efionayi-Mäder is a sociologist and co-director of the SFM. ISBN-10: 2-940379-00-9 ISBN-13: 978-2-940379-00-2 The Path of Somali Refugees into Exile Exile into Refugees Somali of Path The Joëlle Moret, Simone Baglioni, Denise Efionayi-Mäder � � SFM Studies 46 SFM Studies 46 Studies SFM � SFM Studies 46 Joëlle Moret Simone Baglioni Denise Efionayi-Mäder The Path of Somali Refugees into Exile A Comparative -

(IOM) (2019) World Migration Report 2020

WORLD MIGRATION REPORT 2020 The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. This flagship World Migration Report has been produced in line with IOM’s Environment Policy and is available online only. Printed hard copies have not been made in order to reduce paper, printing and transportation impacts. The report is available for free download at www.iom.int/wmr. Publisher: International Organization for Migration 17 route des Morillons P.O. Box 17 1211 Geneva 19 Switzerland Tel.: +41 22 717 9111 Fax: +41 22 798 6150 Email: [email protected] Website: www.iom.int ISSN 1561-5502 e-ISBN 978-92-9068-789-4 Cover photos Top: Children from Taro island carry lighter items from IOM’s delivery of food aid funded by USAID, with transport support from the United Nations. © IOM 2013/Joe LOWRY Middle: Rice fields in Southern Bangladesh. -

Clanship, Conflict and Refugees: an Introduction to Somalis in the Horn of Africa

CLANSHIP, CONFLICT AND REFUGEES: AN INTRODUCTION TO SOMALIS IN THE HORN OF AFRICA Guido Ambroso TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I: THE CLAN SYSTEM p. 2 The People, Language and Religion p. 2 The Economic and Socials Systems p. 3 The Dir p. 5 The Darod p. 8 The Hawiye p. 10 Non-Pastoral Clans p. 11 PART II: A HISTORICAL SUMMARY FROM COLONIALISM TO DISINTEGRATION p. 14 The Colonial Scramble for the Horn of Africa and the Darwish Reaction (1880-1935) p. 14 The Boundaries Question p. 16 From the Italian East Africa Empire to Independence (1936-60) p. 18 Democracy and Dictatorship (1960-77) p. 20 The Ogaden War and the Decline of Siyad Barre’s Regime (1977-87) p. 22 Civil War and the Disintegration of Somalia (1988-91) p. 24 From Hope to Despair (1992-99) p. 27 Conflict and Progress in Somaliland (1991-99) p. 31 Eastern Ethiopia from Menelik’s Conquest to Ethnic Federalism (1887-1995) p. 35 The Impact of the Arta Conference and of September the 11th p. 37 PART III: REFUGEES AND RETURNEES IN EASTERN ETHIOPIA AND SOMALILAND p. 42 Refugee Influxes and Camps p. 41 Patterns of Repatriation (1991-99) p. 46 Patterns of Reintegration in the Waqoyi Galbeed and Awdal Regions of Somaliland p. 52 Bibliography p. 62 ANNEXES: CLAN GENEALOGICAL CHARTS Samaal (General/Overview) A. 1 Dir A. 2 Issa A. 2.1 Gadabursi A. 2.2 Isaq A. 2.3 Habar Awal / Isaq A.2.3.1 Garhajis / Isaq A. 2.3.2 Darod (General/ Simplified) A. 3 Ogaden and Marrahan Darod A.