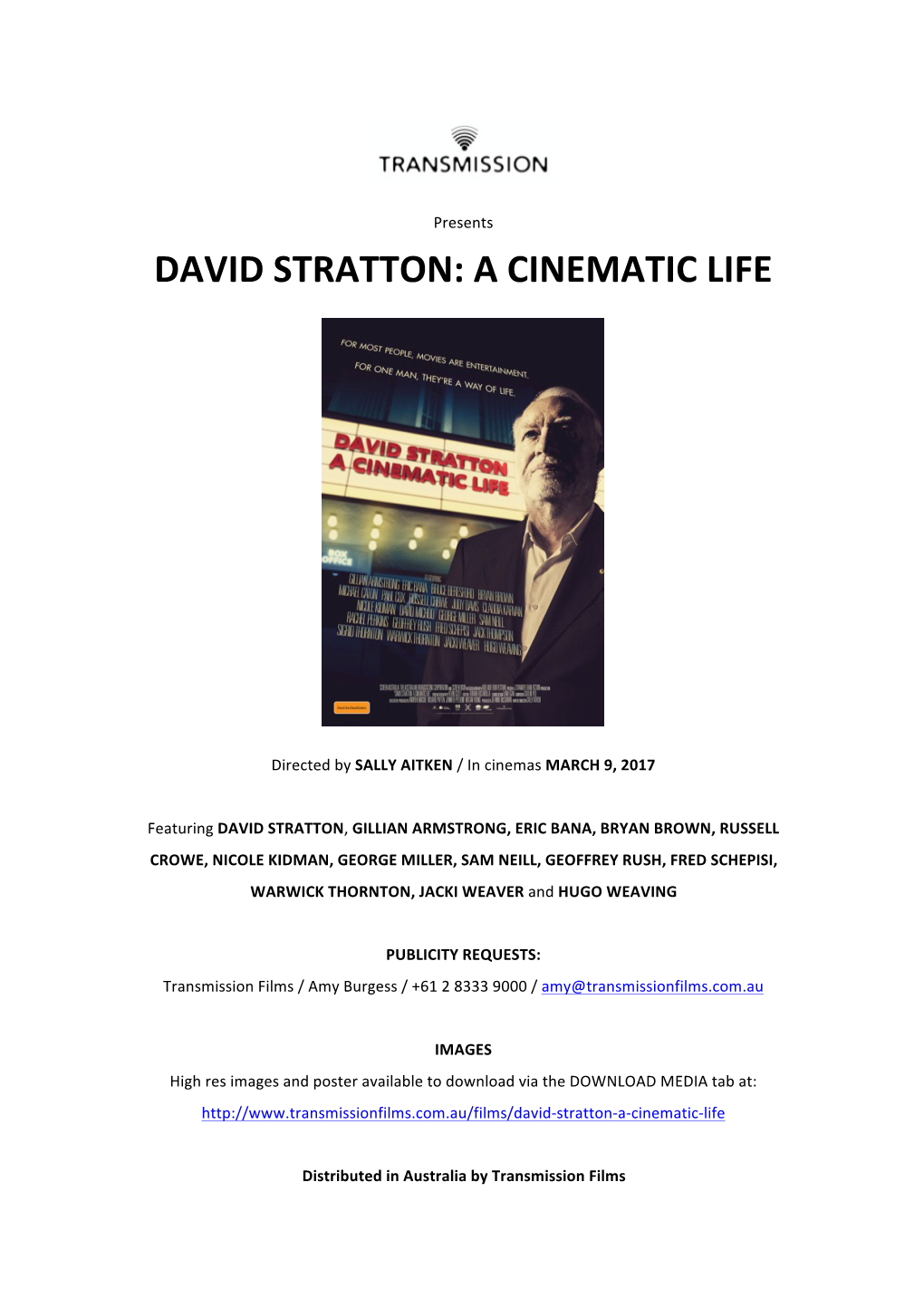

David Stratton: a Cinematic Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bruce Beresford's Breaker Morant Re-Viewed

FILMHISTORIA Online Vol. 30, núm. 1 (2020) · ISSN: 2014-668X The Boers and the Breaker: Bruce Beresford’s Breaker Morant Re-Viewed ROBERT J. CARDULLO University of Michigan Abstract This essay is a re-viewing of Breaker Morant in the contexts of New Australian Cinema, the Boer War, Australian Federation, the genre of the military courtroom drama, and the directing career of Bruce Beresford. The author argues that the film is no simple platitudinous melodrama about military injustice—as it is still widely regarded by many—but instead a sterling dramatization of one of the most controversial episodes in Australian colonial history. The author argues, further, that Breaker Morant is also a sterling instance of “telescoping,” in which the film’s action, set in the past, is intended as a comment upon the world of the present—the present in this case being that of a twentieth-century guerrilla war known as the Vietnam “conflict.” Keywords: Breaker Morant; Bruce Beresford; New Australian Cinema; Boer War; Australian Federation; military courtroom drama. Resumen Este ensayo es una revisión del film Consejo de guerra (Breaker Morant, 1980) desde perspectivas como la del Nuevo Cine Australiano, la guerra de los boers, la Federación Australiana, el género del drama en una corte marcial y la trayectoria del realizador Bruce Beresford. El autor argumenta que la película no es un simple melodrama sobre la injusticia militar, como todavía es ampliamente considerado por muchos, sino una dramatización excelente de uno de los episodios más controvertidos en la historia colonial australiana. El director afirma, además, que Breaker Morant es también una excelente instancia de "telescopio", en el que la acción de la película, ambientada en el pasado, pretende ser una referencia al mundo del presente, en este caso es el de una guerra de guerrillas del siglo XX conocida como el "conflicto" de Vietnam. -

Bryan Brown to Receive Australia's Highest Screen Accolade

Media Release For immediate release Bryan Brown to receive Australia’s highest screen accolade Today, the Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (AACTA) announced that one of Australia’s most admired and respected actors, Bryan Brown, will be honoured with the Australian Academy’s most prestigious award – the Longford Lyell Award. The Award will be presented to Bryan at the 2018 AACTA Awards Ceremony presented by Foxtel on Wednesday 5 December at The Star Event Centre in Sydney, telecast at 8:30pm on Channel 7. Tickets are now on sale from www.aacta.org/whats-on. First presented in 1968, the Longford Lyell Award honours Australian film pioneer Raymond Longford and his partner in filmmaking and life, Lottie Lyell. The Award is the highest honour that the Australian Academy can bestow upon an individual and recognises a person who has made a truly outstanding contribution to the enrichment of Australia’s screen environment and culture. “It's an honour - thank you to the Academy,” said Bryan Brown. “I'm an Australian telling Australian stories and I love it.” Brown first debuted on screen in 1975 as a policeman in SCOBIE MALONE, delivering just two lines. He went on to cut his teeth with some of Australia’s leading directors, with supporting roles throughout 1978 in films such as Fred Schepisi’s THE CHANT OF JIMMIE BLACKSMITH, Bruce Beresford’s MONEY MOVERS and Phillip Noyce’s NEWSFRONT, before taking on leading roles in Donald Crombie’s CATHY’S CHILD (1979) and Albie Thoms’ PALM BEACH (1980). In 1980, Brown received his first AFI Award nominations, becoming the first male actor to be nominated for both Best Lead and Best Supporting Actor in the same year. -

From Mar 2018 Riverside Cinema

RIVERSIDE CINEMA FROM MAR 2018 ALL ABOUT SWEET COUNTRY 40,000 HORSEMEN ALL ABOUT WOMEN Starring Sam Neill and Bryan Brown Starring Chips Rafferty WOMEN SATELLITE SATELLITE Talks and Ideas «««« Featuring a brief introduction by a military Streaming live direct from the Sydney Opera “Unforgettable. A new Australian classic.” expert from the Lancer Barracks Museum and a House, this program invites you to reflect on – The Globe and Mail post-screening critique and Q&A the past and imagine the future of feminism. Join us as we commemorate the 125th Anniversary Featuring 3 headline sessions and an exclusive Directed by Warwick Thornton (Samson and Delilah) backstage interview. and featuring an all-star cast including Sam Neill of the Association of the Royal NSW Lancers with this and Bryan Brown this multi award-winning period special screening of the classic Australian war film. Come along to a session or purchase an event western inspired by real events is a must-see. Starring Chips Rafferty, Charles Chauvel’s cinematic package to all 3 sessions (listed below) and save! Outback Northern Territory, 1929. When Aboriginal tribute to the mounted troops of the Australian Light SUNDAY 4 MARCH stockman Sam kills white station owner Harry March Horse regiments is a rousing call to arms, giving life in self-defence, Sam and his wife Lizzie go on the run. to the heroic tales of mateship during the Great War. They are pursued across the outback, through glorious A box-office smash on release, this is your unique but harsh desert country. But will justice prevail? opportunity to see this now rarely-screened film on FRIDAY 2 MARCH AT 7:30PM the big screen. -

Sight & Sound Films of 2007

Sight & Sound Films of 2007 Each year we ask a selection of our contributors - reviewers and critics from around the world - for their five films of the year. It's a very loosely policed subjective selection, based on films the writer has seen and enjoyed that year, and we don't deny them the choice of films that haven't yet reached the UK. And we don't give them much time to ponder, either - just about a week. So below you'll find the familiar and the obscure, the new and the old. From this we put together the top ten you see here. What distinguishes this particular list is that it's been drawn up from one of the best years for all-round quality I can remember. 2007 has seen some extraordinary films. So all of the films in the ten are must-sees and so are many more. Enjoy. - Nick James, Editor. 1 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (Cristian Mungiu) 2 Inland Empire (David Lynch) 3 Zodiac (David Fincher) = 4 I’m Not There (Todd Haynes) The Lives of Others (Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck) 6 Silent Light (Carlos Reygadas) = 7 The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (Andrew Dominik) Syndromes and a Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul) No Country for Old Men (Ethan and Joel Coen) Eastern Promises (David Cronenberg) 1 Table of Contents – alphabetical by critic Gilbert Adair (Critic and author, UK)............................................................................................4 Kaleem Aftab (Critic, The Independent, UK)...............................................................................4 Geoff Andrew (Critic -

The Premiere Fund Slate for MIFF 2021 Comprises the Following

The MIFF Premiere Fund provides minority co-financing to new Australian quality narrative-drama and documentary feature films that then premiere at the Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF). Seeking out Stories That Need Telling, the the Premiere Fund deepens MIFF’s relationship with filmmaking talent and builds a pipeline of quality Australian content for MIFF. Launched at MIFF 2007, the Premiere Fund has committed to more than 70 projects. Under the charge of MIFF Chair Claire Dobbin, the Premiere Fund Executive Producer is Mark Woods, former CEO of Screen Ireland and Ausfilm and Showtime Australia Head of Content Investment & International Acquisitions. Woods has co-invested in and Executive Produced many quality films, including Rabbit Proof Fence, Japanese Story, Somersault, Breakfast on Pluto, Cannes Palme d’Or winner Wind that Shakes the Barley, and Oscar-winning Six Shooter. ➢ The Premiere Fund slate for MIFF 2021 comprises the following: • ABLAZE: A meditation on family, culture and memory, indigenous Melbourne opera singer Tiriki Onus investigates whether a 70- year old silent film was in fact made by his grandfather – civil rights leader Bill Onus. From director Alex Morgan (Hunt Angels) and producer Tom Zubrycki (Exile in Sarajevo). (Distributor: Umbrella) • ANONYMOUS CLUB: An intimate – often first-person – exploration of the successful, yet shy and introverted, 33-year-old queer Australian musician Courtney Barnett. From producers Pip Campey (Bastardy), Samantha Dinning (No Time For Quiet) & director Danny Cohen. (Dist: Film Art Media) • CHEF ANTONIO’S RECIPES FOR REVOLUTION: Continuing their series of food-related social-issue feature documentaries, director Trevor Graham (Make Hummus Not War) and producer Lisa Wang (Monsieur Mayonnaise) find a very inclusive Italian restaurant/hotel run predominately by young disabled people. -

David Stratton's Stories of Australian Cinema

David Stratton’s Stories of Australian Cinema With thanks to the extraordinary filmmakers and actors who make these films possible. Presenter DAVID STRATTON Writer & Director SALLY AITKEN Producers JO-ANNE McGOWAN JENNIFER PEEDOM Executive Producer MANDY CHANG Director of Photography KEVIN SCOTT Editors ADRIAN ROSTIROLLA MARK MIDDIS KARIN STEININGER HILARY BALMOND Sound Design LIAM EGAN Composer CAITLIN YEO Line Producer JODI MADDOCKS Head of Arts MANDY CHANG Series Producer CLAUDE GONZALES Development Research & Writing ALEX BARRY Legals STEPHEN BOYLE SOPHIE GODDARD SC SALLY McCAUSLAND Production Manager JODIE PASSMORE Production Co-ordinator KATIE AMOS Researchers RACHEL ROBINSON CAMERON MANION Interview & Post Transcripts JESSICA IMMER Sound Recordists DAN MIAU LEO SULLIVAN DANE CODY NICK BATTERHAM Additional Photography JUDD OVERTON JUSTINE KERRIGAN STEPHEN STANDEN ASHLEIGH CARTER ROBB SHAW-VELZEN Drone Operators NICK ROBINSON JONATHAN HARDING Camera Assistants GERARD MAHER ROB TENCH MARK COLLINS DREW ENGLISH JOSHUA DANG SIMON WILLIAMS NICHOLAS EVERETT ANTHONY RILOCAPRO LUKE WHITMORE Hair & Makeup FERN MADDEN DIANE DUSTING NATALIE VINCETICH BELINDA MOORE Post Producers ALEX BARRY LISA MATTHEWS Assistant Editors WAYNE C BLAIR ANNIE ZHANG Archive Consultant MIRIAM KENTER Graphics Designer THE KINGDOM OF LUDD Production Accountant LEAH HALL Stills Photographers PETER ADAMS JAMIE BILLING MARIA BOYADGIS RAYMOND MAHER MARK ROGERS PETER TARASUIK Post Production Facility DEFINITION FILMS SYDNEY Head of Post Production DAVID GROSS Online Editor -

1 Picturing a Golden Age: September and Australian Rules Pauline Marsh, University of Tasmania It Is 1968, Rural Western Austra

1 Picturing a Golden Age: September and Australian Rules Pauline Marsh, University of Tasmania Abstract: In two Australian coming-of-age feature films, Australian Rules and September, the central young characters hold idyllic notions about friendship and equality that prove to be the keys to transformative on- screen behaviours. Intimate intersubjectivity, deployed in the close relationships between the indigenous and nonindigenous protagonists, generates multiple questions about the value of normalised adult interculturalism. I suggest that the most pointed significance of these films lies in the compromises that the young adults make. As they reach the inevitable moral crisis that awaits them on the cusp of adulthood, despite pressures to abandon their childhood friendships they instead sustain their utopian (golden) visions of the future. It is 1968, rural Western Australia. As we glide along an undulating bitumen road up ahead we see, from a low camera angle, a school bus moving smoothly along the same route. Periodically a smattering of roadside trees filters the sunlight, but for the most part open fields of wheat flank the roadsides and stretch out to the horizon, presenting a grand and golden vista. As we reach the bus, music that has hitherto been a quiet accompaniment swells and in the next moment we are inside the vehicle with a fair-haired teenager. The handsome lad, dressed in a yellow school uniform, is drawing a picture of a boxer in a sketchpad. Another cut takes us back outside again, to an equally magnificent view from the front of the bus. This mesmerising piece of cinema—the opening of September (Peter Carstairs, 2007)— affords a viewer an experience of tranquillity and promise, and is homage to the notion of a golden age of youth. -

Windmill Theatre, GIRL ASLEEP Is a Journey Into the Absurd, Scary and Beautiful Heart of the Teenage Mind

1 WINNER ADEL AIDE FILM FESTIVAL FOXTEL MOVIES AUDIENCE AWARDS MOST POPULAR FEATURE Girl Asleep bags most popular feature at Adelaide Film Festival. IF MAGAZINE It’s in Myers’s commitment to eccentricity that Girl Asleep – an art-house film made firmly with a teenage audience in its sight – finds its heart. THE GUARDIAN AUSTRALIA Girl Asleep is the stylish, formally exuberant debut of theatre director Rosemary Myers. A funny and imaginative portrait of growing pains. THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER With the endless production of superhero films and film remakes these days, it is refreshing to see a film with such raw acting and originality from start to finish. It’s hard not to fall in love with the characters in Girl Asleep, and be left with the warmth of the film long after the credits have stop rolling. THE UPSIDE NEWS Inventive and confidently executed... bright and occasionally subversive take on teen growing pains that gives fresh legs to a familiar genre. We’re lucky to call this one our own. RIP IT UP Profoundly funny. SCENESTR Wildly funny and deeply moving in equal measure, it is a work rich in larrikin character but universal in its themes and appeal. As Greta embraces her blossoming self, so to does Australian cinema welcome another memorable movie heroine. SCREEN SPACE A memorable, comic balance of poise and chaos. ADELAIDE REVIEW Colourful, eccentric... production about a girl navigating the pitfalls of puberty with a casual side of magical realism... one for fans of coming-of-age dramas and colourful Wes Anderson-style quirkfests. -

What Killed Australian Cinema & Why Is the Bloody Corpse Still Moving?

What Killed Australian Cinema & Why is the Bloody Corpse Still Moving? A Thesis Submitted By Jacob Zvi for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Faculty of Health, Arts & Design, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne © Jacob Zvi 2019 Swinburne University of Technology All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. II Abstract In 2004, annual Australian viewership of Australian cinema, regularly averaging below 5%, reached an all-time low of 1.3%. Considering Australia ranks among the top nations in both screens and cinema attendance per capita, and that Australians’ biggest cultural consumption is screen products and multi-media equipment, suggests that Australians love cinema, but refrain from watching their own. Why? During its golden period, 1970-1988, Australian cinema was operating under combined private and government investment, and responsible for critical and commercial successes. However, over the past thirty years, 1988-2018, due to the detrimental role of government film agencies played in binding Australian cinema to government funding, Australian films are perceived as under-developed, low budget, and depressing. Out of hundreds of films produced, and investment of billions of dollars, only a dozen managed to recoup their budget. The thesis demonstrates how ‘Australian national cinema’ discourse helped funding bodies consolidate their power. Australian filmmaking is defined by three ongoing and unresolved frictions: one external and two internal. Friction I debates Australian cinema vs. Australian audience, rejecting Australian cinema’s output, resulting in Frictions II and III, which respectively debate two industry questions: what content is produced? arthouse vs. -

The Cinema of Giorgio Mangiamele

WHO IS BEHIND THE CAMERA? The cinema of Giorgio Mangiamele Silvana Tuccio Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August, 2009 School of Culture and Communication The University of Melbourne Who is behind the camera? Abstract The cinema of independent film director Giorgio Mangiamele has remained in the shadows of Australian film history since the 1960s when he produced a remarkable body of films, including the feature film Clay, which was invited to the Cannes Film Festival in 1965. This thesis explores the silence that surrounds Mangiamele’s films. His oeuvre is characterised by a specific poetic vision that worked to make tangible a social reality arising out of the impact with foreignness—a foreign society, a foreign country. This thesis analyses the concept of the foreigner as a dominant feature in the development of a cinematic language, and the extent to which the foreigner as outsider intersects with the cinematic process. Each of Giorgio Mangiamele’s films depicts a sharp and sensitive picture of the dislocated figure, the foreigner apprehending the oppressive and silencing forces that surround his being whilst dealing with a new environment; at the same time the urban landscape of inner suburban Melbourne and the natural Australian landscape are recreated in the films. As well as the international recognition given to Clay, Mangiamele’s short films The Spag and Ninety-Nine Percent won Australian Film Institute awards. Giorgio Mangiamele’s films are particularly noted for their style. This thesis explores the cinematic aesthetic, visual style and language of the films. -

1 21-24 July 2011

MIFF 37ºSouth Market is the Australia/NZ partner of London’s Production Finance Market (PFM) & Canada’s Strategic Partners www.miff37degreesSouth.com 21-24 July 2011 2011: Distribution, Sales & Financing Executives London Production Finance Market (PFM) Company Profile The London Production Finance Market (PFM) occurs each October in association with The BFI London Film Festival and is supported by the London Development Agency, UK Film Council, UK Trade and Investment (UKTI), Skillset, City of London Corporation and Peacefulfish. The invitation-only PFM registers around 50 producers and more than 150 projects with over US$1 billion of production value and around 60 financing guests including UGC, Rai Cinema, Miramax, Studio Canal, Lionsgate, Nordisk, Ingenious, Celluloid Dreams, Aramid, Focus, Natixis, Bank of Ireland, Sony Pictures Classics, Warner Bros. and Paramount. Film London is the UK capital's film and media agency. It sustains, promotes and develops London as a major film-making and film cultural capital. This includes all the screen industries based in London - film, television, video, commercials and new interactive media. Helena MacKenzie started her career in the film industry at the age of 19 when she thought she would try and get a job in the entertainment industry as a way out of going to Medical School. It worked! Many years and a few jobs later she is now the Head of International at Film London. Her journey to Film London has crossed many paths of international production, distribution and international sales. At Film London, she devised and runs the Film Passport Programme, runs the London UK Film Focus, the Production Finance Market (PFM), and Film London’s Film Commission services as well as working with emerging markets such as China, India and Russia. -

Jill Bilcock: Dancing the Invisible

JILL BILCOCK: DANCING THE INVISIBLE PRESS KIT Written and Directed by Axel Grigor Produced by Axel Grigor and Faramarz K-Rahber Executive Produced by Sue Maslin Distributed by Film Art Media Production Company: Distributor: Faraway Productions Pty Ltd FILM ART MEDIA PO Box 1602 PO Box 1312 Carindale QLD 4152 Collingwood VIC 3066 AUSTRALIA AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Phone: +61 3 9417 2155 faraway.com.au Email: [email protected] filmartmedia.com BILLING BLOCK FILM ART MEDIA, SOUNDFIRM, SCREEN QUEENSLAND and FILM VICTORIA in association with SCREEN AUSTRALIA, THE AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION and GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY present JILL BILCOCK: DANCING THE INVISIBLE Featuring CATE BLANCHETT, BAZ LUHRMANN, SHEKHAR KAPUR and RACHEL GRIFFITHS in a FARAWAY PRODUCTIONS FILM FILM EDITORS SCOTT WALTON & AXEL GRIGOR DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY FARAMARZ K-RAHBER PRODUCTION MANAGER TARA WARDROP PRODUCERS AXEL GRIGOR & FARAMARZ K-RAHBER EXECUTIVE PRODUCER SUE MASLIN © 2017 Faraway Productions Pty Ltd and Soundfirm Pty Ltd. TECHNICAL INFORMATION Format DCP, Pro Res File Genre Documentary Country of Production AUSTRALIA Year of Production 2017 Running Time 78mins Ratio 16 x 9 Language ENGLISH /2 LOGLINE The extraordinary life and artistry of internationally acclaimed film editor, Jill Bilcock. SHORT SYNOPSIS A documentary about internationally renowned film editor Jill Bilcock, that charts how an outspoken arts student in 1960s Melbourne became one of the world’s most acclaimed film artists. SYNOPSIS Jill Bilcock: Dancing The Invisible focuses on the life and work of one of the world’s leading film artists, Academy award nominated film editor Jill Bilcock. Iconic Australian films Strictly Ballroom, Muriel’s Wedding, Moulin Rouge!, Red Dog, and The Dressmaker bear the unmistakable look and sensibility of Bilcock’s visual inventiveness, but it was her brave editing choices in Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo+Juliet that changed the look of cinema the world over, inspiring one Hollywood critic to dub her editing style as that of a “Russian serial killer on crack”.