The Second Kind of Sin: Making the Case for a Duty to Disclose Facts Related to Genericism and Functionality in the Trademark Office

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Union Calendar No. 481 104Th Congress, 2D Session – – – – – – – – – – – – House Report 104–879

1 Union Calendar No. 481 104th Congress, 2d Session ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± House Report 104±879 REPORT ON THE ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES DURING THE ONE HUNDRED FOURTH CONGRESS PURSUANT TO CLAUSE 1(d) RULE XI OF THE RULES OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES JANUARY 2, 1997.ÐCommitted to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 36±501 WASHINGTON : 1997 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FOURTH CONGRESS HENRY J. HYDE, Illinois, Chairman 1 CARLOS J. MOORHEAD, California JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., PATRICIA SCHROEDER, Colorado Wisconsin BARNEY FRANK, Massachusetts BILL MCCOLLUM, Florida CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York GEORGE W. GEKAS, Pennsylvania HOWARD L. BERMAN, California HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina RICH BOUCHER, Virginia LAMAR SMITH, Texas JOHN BRYANT, Texas STEVEN SCHIFF, New Mexico JACK REED, Rhode Island ELTON GALLEGLY, California JERROLD NADLER, New York CHARLES T. CANADY, Florida ROBERT C. SCOTT, Virginia BOB INGLIS, South Carolina MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia XAVIER BECERRA, California STEPHEN E. BUYER, Indiana JOSEÂ E. SERRANO, New York 2 MARTIN R. HOKE, Ohio ZOE LOFGREN, California SONNY BONO, California SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas FRED HEINEMAN, North Carolina MAXINE WATERS, California 3 ED BRYANT, Tennessee STEVE CHABOT, Ohio MICHAEL PATRICK FLANAGAN, Illinois BOB BARR, Georgia ALAN F. COFFEY, JR., General Counsel/Staff Director JULIAN EPSTEIN, Minority Staff Director 1 Henry J. Hyde, Illinois, elected to the Committee as Chairman pursuant to House Resolution 11, approved by the House January 5 (legislative day of January 4), 1995. -

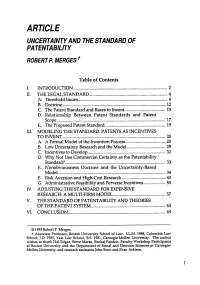

Uncertainty and the Standard of Patentability Robert P

ARTICLE UNCERTAINTY AND THE STANDARD OF PATENTABILITY ROBERT P. MERGES" Table of Contents I. INTRODU CTION ................................................................................ 2 II. THE LEGAL STANDARD .................................................................. 4 A . Threshold Issues ............................................................................ 4 B. Doctrine .......................................................................................... 12 C. The Patent Standard and Races to Invent ................................. 15 D. Relationship Between Patent Standards and Patent Scop e ............................................................................................. .. 17 E. The Proposed Patent Standard ................................................... 19 II1. MODELING THE STANDARD: PATENTS AS INCENTIVES TO IN V EN T ........................................................................................ 20 A. A Formal Model of the Invention Process ............................... 20 B. Low Uncertainty Research and the Model ............................... 29 C. Incentives to Develop ................................................................. 32 D. Why Not Use Commercial Certainty as the Patentability Standard? ................................................. ................................... 33 E. Nonobviousness Doctrine and the Uncertainty-Based Model ............................................................................................. 34 F. Risk Aversion and High-Cost -

Confusing Patent Eligibility

CONFUSING PATENT ELIGIBILITY DAVID 0. TAYLOR* INTRODUCTION ................................................. 158 I. CODIFYING PATENT ELIGIBILITY ....................... 164 A. The FirstPatent Statute ........................... 164 B. The Patent Statute Between 1793 and 1952................... 166 C. The Modern Patent Statute ................ ..... 170 D. Lessons About Eligibility Law ................... 174 II. UNRAVELING PATENT ELIGIBILITY. ........ ............. 178 A. Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs............ 178 B. Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank Int'l .......... .......... 184 III. UNDERLYING CONFUSION ........................... 186 A. The Requirements of Patentability.................................. 186 B. Claim Breadth............................ 188 1. The Supreme Court's Underlying Concerns............ 189 2. Existing Statutory Requirements Address the Concerns with Claim Breadth .............. 191 3. The Supreme Court Wrongly Rejected Use of Existing Statutory Requirements to Address Claim Breadth ..................................... 197 4. Even if § 101 Was Needed to Exclude Patenting of Natural Laws and Phenomena, A Simple Statutory Interpretation Would Do So .................... 212 C. Claim Abstractness ........................... 221 1. Problems with the Supreme Court's Test................221 2. Existing Statutory Requirements Address Abstractness, Yet the Supreme Court Has Not Even Addressed Them.............................. 223 IV. LACK OF ADMINISTRABILITY ....................... ....... 227 A. Whether a -

Distinctive and Distinguishable Trademarks

JUNE 25, 2005 MAKING A NAME – DISTINCTIVE AND DISTINGUISHABLE TRADEMARKS By Kam W. Li, Esq. Procopio, Cory, Hargreaves & Savitch LLP The objective is to create a valuable trademark, and the strategy is to adopt one that is distinctive and distinguishable. Trademarks are symbols, such as words, names, logos and other devices, used by companies to identify their products and services 1. When such use of a symbol has the effect of creating a mental association between it and the company’ products and services, the symbol is said to acquire trademark significance, and serves as a means to identify the source of the products or services. The mental association of the trademark to a company’s products and services is what gives value to the trademark. 2 How deep, how intense and how enduring that effect is depends on how the company drives its branding strategy. The following perspectives should help a company to build, maintain, exploit and protect this value. Chart 1 BRAND VALUES 80 70 60 50 40 30 $Billion 20 10 0 T A Y F M EL E GE T KI IB COLA SO IN SN A NO DI C RO IC CO M MARLBOROMERCEDES McDONALD's Brands Source: Business Week: August 4, 2003 DEFINE TRADEMARK STRATEGY TO BUILD BRAND A company’s trademark strategy should aim at building a strong brand identity, which creates awareness, perceived quality and loyalty. These latter attributes are the building blocks of the value in the trademark and should be part of the criteria for trademark selection and adoption. Manifesting the brand value, a strong trademark differentiates the company with its competitors and conveys a commercial connotation as to what the company can and will do over time. -

Patent Law: a Handbook for Congress

Patent Law: A Handbook for Congress September 16, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46525 SUMMARY R46525 Patent Law: A Handbook for Congress September 16, 2020 A patent gives its owner the exclusive right to make, use, import, sell, or offer for sale the invention covered by the patent. The patent system has long been viewed as important to Kevin T. Richards encouraging American innovation by providing an incentive for inventors to create. Without a Legislative Attorney patent system, the reasoning goes, there would be little incentive for invention because anyone could freely copy the inventor’s innovation. Congressional action in recent years has underscored the importance of the patent system, including a major revision to the patent laws in 2011 in the form of the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act. Congress has also demonstrated an interest in patents and pharmaceutical pricing; the types of inventions that may be patented (also referred to as “patentable subject matter”); and the potential impact of patents on a vaccine for COVID-19. As patent law continues to be an area of congressional interest, this report provides background and descriptions of several key patent law doctrines. The report first describes the various parts of a patent, including the specification (which describes the invention) and the claims (which set out the legal boundaries of the patent owner’s exclusive rights). Next, the report provides detail on the basic doctrines governing patentability, enforcement, and patent validity. For patentability, the report details the various requirements that must be met before a patent is allowed to issue. -

TRIPS and Pharmaceutical Patents

FACT SHEET September 2003 TRIPS and pharmaceutical patents CONTENTS Philosophy: TRIPS attempts to strike a balance 1 What is the basic patent right? 2 A patent is not a permit to put a product on the market 2 Under TRIPS, what are member governments’ obligations on pharmaceutical patents? 2 IN GENERAL (see also “exceptions”) 2 Exceptions 3 ELIGIBILITY FOR PATENTING 3 RESEARCH EXCEPTION AND “BOLAR” PROVISION 3 ANTI-COMPETITIVE PRACTICE, ETC 4 COMPULSORY LICENSING 4 WHAT ARE THE GROUNDS FOR USING COMPULSORY LICENSING? 5 PARALLEL IMPORTS, GREY IMPORTS AND ‘EXHAUSTION’ OF RIGHTS 5 THE DOHA DECLARATION ON TRIPS AND PUBLIC HEALTH 5 IMPORTING UNDER COMPULSORY LICENSING (‘PAR.6’) 6 What does ‘generic’ mean? 6 Developing countries’ transition periods 7 GENERAL 7 PHARMACEUTICALS AND AGRICULTURAL CHEMICALS 7 For more information 8 The TRIPS Agreement Philosophy: TRIPS attempts to strike a balance Article 7 Objectives The WTO’s Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of The protection and enforcement of intellectual property Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) attempts to strike rights should contribute to the promotion of technological innovation and to the transfer and a balance between the long term social objective of dissemination of technology, to the mutual advantage providing incentives for future inventions and of producers and users of technological knowledge and creation, and the short term objective of allowing in a manner conducive to social and economic welfare, and to a balance of rights and obligations. people to use existing inventions and creations. The agreement covers a wide range of subjects, from Article 8 copyright and trademarks, to integrated circuit Principles designs and trade secrets. -

Duty of Disclosure for Insurance Contracts: a Comparative Note of the United Kingdom and Indonesia

Corporate and Trade Law Review Volume 01 Issue 01 January = June 2021 Duty of Disclosure for Insurance Contracts: A Comparative Note of the United Kingdom and Indonesia Shanty Ika Yuniarti Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands Article Info ABSTRACT Keyword: Duty of disclosure is one of the most essential aspects of an insurance contract. Its role in an insurance contract is to avoid fraud and duty of disclosure; misinterpretations. A person seeking insurance must act in good faith, insurance contracts; and good faith requires to disclose every material fact known, related misrepresentation; to the risk. It begins with the proposer for the insurance policy that is contract law; obliged to disclose all information to the insurer. However, there is a possibility either the insured or insurer done a breach of duty of insurance law disclosure. Breach of duty of disclosure includes Non-Disclosure and Misrepresentation. Breach of duty of disclosure also possible to happen in the Pre-Contractual and Post-Contractual Stage in an Article History: insurance contract due to either a deliberate, reckless, or innocent Received: 23 Jun 2020 breach. The duty of disclosure in each country might be different depends on its jurisdiction, for example, the United Kingdom as a Reviewed: 25 Sept 2020 common law country and Indonesia as a civil law country. Accepted: 26 Oct 2020 Published: 18 Dec 2020 ABSTRAK Corresponding Author: Kewajiban pengungkapan adalah salah satu aspek terpenting dari kontrak asuransi. Perannya dalam kontrak asuransi adalah untuk Email: menghindari penipuan dan salah tafsir. Seseorang yang mencari [email protected] asuransi harus bertindak dengan itikad baik, dan itikad baik mensyaratkan untuk mengungkapkan setiap fakta material yang diketahui, terkait dengan risiko. -

May 2, 2019 Public Meeting

UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE PATENT PUBLIC ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEETING QUARTERLY MEETING Alexandria, Virginia Thursday, May 2, 2019 PARTICIPANTS: PPAC Members: MARYLEE JENKINS, Chair JENNIFER CAMACHO BEARNARD CASSIDY STEVEN CALTRIDER CATHERINE FAINT MARK GOODSON BERNIE KNIGHT DAN LANG JULIE MAR-SPINOLA PAMELA SCHWARTZ JEFFREY SEARS USPTO: ANDREI IANCU, Under Secretary of Commerce for Intellectual Property and Director of the USPTO BOB BAHR, Deputy Commissioner for Patent Examination Policy THOMAS BEACH, PE2E & PTAB Portfolio Manager SCOTT BOALICK, Chief Judge, Patent Trial and Appeal Board JACKIE BONILLA, Deputy Chief Judge, Patent Trial and Appeal Board DANA COLARULLI, Director, Office of Governmental Affairs JOHN COTTINGHAM, Director, Central Reexamination Unit CHELSEA D'ANGONA, Customer Experience Administrator for Patents ELIZABETH DOUGHERTY, Atlantic Outreach Liaison ANDREW FAILE, Deputy Commissioner for Patent Operations DAVID GERK, Patent Attorney, Office of Policy and International Affairs DREW HIRSHFELD, Commissioner for Patents JAMIE HOLCOMBE, Chief Information Officer MARIA HOLTMANN, Director of International Programs, Office of International Patent Cooperation JAMES KRAMER, Director, Technology Center 2400 MIKE NEAS, Deputy Director, International Patent and Legal Administration SHIRA PERLMUTTER, Chief Policy Officer and Director for International Affairs JASON REPKO, Administrative Patent Judge, Patent Trial and Appeal Board BRANDEN RITCHIE, Senior Legal Advisor, Office of the Under Secretary and Director ANTHONY SCARDINO, Chief Financial Officer, USPTO RICK SEIDEL, Deputy Commissioner of Patent Administration ANDREW TOOLE, Chief Economist, Office of Policy and International Affairs VALENCIA MARTIN WALLACE, Deputy Commissioner for Patent Quality DAVID WILEY, Director, Technology Center 2100 REMY YUCEL, Assistant Deputy Commissioner for Patent Operations Other Participants: KATHLEEN DUDA DAN RYMAN * * * * * P R O C E E D I N G S (9:00 a.m.) MS. -

May 12, 2017 to Solicit the Parties’ Views on Any Evidentiary Hearing to Be Held

CONTRA COSTA SUPERIOR COURT MARTINEZ, CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT: 12 HEARING DATE: 05/12/17 1. TIME: 9:00 CASE#: MSC15-01760 CASE NAME: WALKER VS. WEST WIND DRIVE-IN HEARING ON MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT FILED BY SYUFY ENTERPRISES, LP * TENTATIVE RULING: * Defendant Syufy Enterprises, LP files this motion for summary judgment. As captioned, the motion is facially defective because it would not dispose of the entire action and result in entry of judgment in the case. In the interest of justice, however (and bearing in mind the proximity of the trial date), the Court will treat the motion as one for summary adjudication as to the first cause of action for premises liability and the third cause of action for negligence. The parties have supported, opposed, and briefed the motion as if it were a motion for summary adjudication. The motion is denied. The present motion rests entirely on what is asserted to be a release agreement found in the original contract between the parties. The Court holds, as a matter of law, that the purported release language is not a release of claims as between these two parties, but rather an indemnification provision as to any third-party claims brought against Syufy due to Walker’s use of Syufy’s facilities. This case arises from a swap meet occurring on premises owned by defendant Syufy. Plaintiff Walker purchased a vendor ticket, an agreement entitling her to sell goods at the swap meet. The challenged counts assert liability for negligence and premises liability, arising from Walker’s injury allegedly caused by catching her foot in a pothole on the premises. -

Wipo Regional Workshop on Ipas for Trademark Examiners

WIPO REGIONAL WORKSHOP ON IPAS FOR TRADEMARK EXAMINERS COUNTRY REPORT: IP OFFICE AUTOMATION STATUS, STATISTICS & FUTURE PLANS GABRONE, BOTSWANA, JULY 10 TO 14, 2017 Prepared by: YUSUPHA M. CHAM TRADEMARK EXAMINER & IPAS ADMINISTRATOR Intellectual property in the Gambia is divided into the two main areas of Industrial Property and copyright and related rights. Industrial property is under the Attorney General's Chambers and Ministry of Justice. Copyright is administered by Ministry of Tourism and Culture through the National Council for Arts and Culture. Industrial Property Act Vol. 15 Cap 95:01 Laws of The Gambia 2009. Industrial Property (Amendment) Act 2015. The Act is supplemented by the Industrial Property Regulations 2010. The Act came into force on the 2nd April 2007 and repealed the following Acts which were applicable in The Gambia: a. The Registration of United Kingdom Patent Act,1925; b. The United Kingdom Designs(Protection) Act,1936; and c. The Trademark Act,1916 The Gambia is a member of the following: The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) since 1980 The African Regional Intellectual property Organization (ARIPO) Signatory of the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) The Berne Convention Harare Protocol Banjul Protocol On Marks (pending) Swakopmund Protocol On the protection of Traditional Knowledge and expressions of folklore (pending) - Instrument deposited Madrid Protocol REGISTRAR GENERAL SENIOR STATE COUNSELS REGISTRAR OF SUBSTANTIVE TRADEMARKS & EXAMINERS PATENTS FORMALITY ACCOUNTS EXAMINERS ICT, SUPERVISOR & RECEPTIONIST DATA ENTRY CLERKS Installed IPAS Centura since 2012 upgraded to 2.7.0 in 2014 Currently using IPAS 2.7.C After the installation of the IPAS System, the office started capturing data and processing them. -

Handbook on Civil Discovery Practice

MIDDLE DISTRICT DISCOVERY A HANDBOOK ON CIVIL DISCOVERY PRACTICE IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF FLORIDA Rev. 6/05/15 Introduction The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, the Local Rules of the Middle District of Florida, and existing case law cover only some aspects of civil discovery practice. Many of the gaps have been filled by the actual practice of trial attorneys and, over the years, a custom and usage has developed in this district in frequently recurring discovery situations. Originally developed by a group of trial attorneys, this handbook on civil discovery practice in the United States District Court, Middle District of Florida, updated in 2001, and again in 2015, attempts to supplement the rules and decisions by capturing this custom and practice. This handbook is neither substantive law nor inflexible rule; it is an expression of generally acceptable discovery practice in the Middle District. It is revised only periodically and should not be relied on as an up-to-date reference regarding the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, the Local Rules for the Middle District of Florida, or existing case law. Judges and attorneys practicing in the Middle District should regard the handbook as highly persuasive in addressing discovery issues. Parties who represent themselves (“pro se”) will find the handbook useful as they are also subject to the rules and court orders and may be sanctioned for non-compliance. Judges may impose specific discovery requirements in civil cases, by standing order or case-specific order. This handbook does not displace those requirements, but provides a general overview of discovery practice in the Middle District of Florida. -

(2010) 188 Cal.App.4Th 1510

Filed 10/6/10 CERTIFIED FOR PUBLICATION IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA FOURTH APPELLATE DISTRICT DIVISION THREE PHIL HOLMES et al., Plaintiffs and Appellants, G041906 v. (Super. Ct. No. 30-2008-00110902) SIEGLINDE SUMMER et al., O P I N I O N Defendants and Respondents. Appeal from a judgment of the Superior Court of Orange County, David R. Chaffee, Judge. Reversed. Adorno Yoss Alvarado & Smith, Keith E. McCullough and Kevin A. Day for Plaintiffs and Appellants. Harbin & McCarron, Richard H. Coombs, Jr., and Andrew McCarron for Defendants and Respondents. Particularly in these days of rampant foreclosures and short sales, “[t]he manner in which California‟s licensed real estate brokers and salesmen conduct business is a matter of public interest and concern. [Citations.]” (Wilson v. Lewis (1980) 106 Cal.App.3d 802, 805-806.) When the real estate professionals involved in the purchase and sale of a residential property do not disclose to the buyer that the property is so greatly overencumbered that it is almost certain clear title cannot be conveyed for the agreed upon price, the transaction is doomed to fail. Not only is the buyer stung, but the marketplace is disrupted and the stream of commerce is impeded. When properties made unsellable by their debt load are listed for sale without appropriate disclosures and sales fall through, purchasers become leery of the marketplace and lenders preparing to extend credit to those purchasers waste valuable time in processing useless loans. In the presently downtrodden economy, it behooves us all for business transactions to come to fruition and for the members of the public to have confidence in real estate agents and brokers.