7902201 Otey, Rheba Washington an Inquiry Into

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

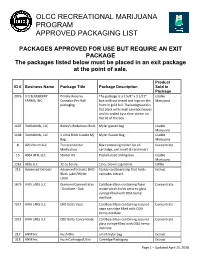

Olcc Recreational Marijuana Program Approved Packaging List

OLCC RECREATIONAL MARIJUANA PROGRAM APPROVED PACKAGING LIST PACKAGES APPROVED FOR USE BUT REQUIRE AN EXIT PACKAGE The packages listed below must be placed in an exit package at the point of sale. Product ID # Business Name Package Title Package Description Sold in Package 2076 3 D BLUEBERRY Private Reserve The package is a 2 5/8" x 3 1/12" Usable FARMS, INC. Cannabis Pre-Roll box with our brand and logo on the Marijuana packaging front in gold foil. The background is flat black with small cannabis leaves and its sealed by a clear sticker on the lid of the box. 1107 3Littlebirds, LLC Bobby's Bodacious Buds Mylar gusset bag Usable Marijuana 1108 3Littlebirds, LLC 3 Little Birds Usable Mj Mylar Gusset Bag Usable Bag Marijuana 8 420 Pharm LLC Transcendental Box containing holder for oil Concentrate Medication cartridge, cart inself & card insert 15 4964 BFH, LLC Starter Kit Pocket-sized sliding box. Usable Marijuana 1262 Ablis LLC 12 oz bottle 12 oz crown cap bottle Edible 213 Advanced Extracts Advanced Extracts BHO Sturdy cardboard slip that holds Extract Black Label/White cannabis extract. Label. 1679 AIRA LABS LLC Diamond Concentrates Cardboard box containing foam Concentrate - Distillate - Dab matte which holds secured glass syringe filled with ODA hemp distillate 1921 AIRA LABS LLC CBD Delta Vape Cardboard box containing secured Concentrate vape cartridge filled with ODA hemp distillate 1922 AIRA LABS LLC CBD Delta Concentrate Cardboard box containing secured Concentrate glass syringe filled with ODA hemp distillate 217 ANM Inc. Hush Bho small mylar bag Extract 218 ANM Inc. -

A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker

LIBRARY v A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker A Dictionary of Men's Wear (This present book) Cloth $2.50, Half Morocco $3.50 A Dictionary of Engraving A handy manual for those who buy or print pictures and printing plates made by the modern processes. Small, handy volume, uncut, illustrated, decorated boards, 75c A Dictionary of Advertising In preparation A Dictionary of Men's Wear Embracing all the terms (so far as could be gathered) used in the men's wear trades expressiv of raw and =; finisht products and of various stages and items of production; selling terms; trade and popular slang and cant terms; and many other things curious, pertinent and impertinent; with an appendix con- taining sundry useful tables; the uniforms of "ancient and honorable" independent military companies of the U. S.; charts of correct dress, livery, and so forth. By William Henry Baker Author of "A Dictionary of Engraving" "A good dictionary is truly very interesting reading in spite of the man who declared that such an one changed the subject too often." —S William Beck CLEVELAND WILLIAM HENRY BAKER 1908 Copyright 1908 By William Henry Baker Cleveland O LIBRARY of CONGRESS Two Copies NOV 24 I SOB Copyright tntry _ OL^SS^tfU XXc, No. Press of The Britton Printing Co Cleveland tf- ?^ Dedication Conforming to custom this unconventional book is Dedicated to those most likely to be benefitted, i. e., to The 15000 or so Retail Clothiers The 15000 or so Custom Tailors The 1200 or so Clothing Manufacturers The 5000 or so Woolen and Cotton Mills The 22000 -

Friesian Division Must Be Members of IFSHA Or Pay to IFSHA a Non Member Fee for Each Competition in Which Competing

CHAPTER FR FRIESIAN AND PART BRED FRIESIAN SUBCHAPTER FR1 GENERAL QUALIFICATIONS FR101 Eligibility to Compete FR102 Falls FR103 Shoeing and Hoof Specifications FR104 Conformation for all horses SUBCHAPTER FR-2 IN-HAND FR105 Purebred Friesian FR106 Part Bred Friesian FR107 General FR108 Tack FR109 Attire FR110 Judging Criteria for In-Hand and Specialty In-Hand Classes FR111 Class Specifications for In-Hand and Specialty In-Hand classes FR112 Presentation for In-Hand Classes FR113 Get of Sire and Produce of Dam (Specialty In-Hand Classes) FR114 Friesian Baroque In-Hand FR115 Dressage and Sport Horse In-Hand FR116 Judging Criteria FR117 Class Specifications FR118 Championships SUBCHAPTER FR-3 PARK HORSE FR119 General FR120 Qualifying Gaits FR121 Tack FR122 Attire FR123 Judging Criteria SUBCHAPTER FR-4 ENGLISH PLEASURE SADDLE SEAT FR124 General FR125 Qualifying Gaits FR126 Tack FR127 Attire FR128 Judging Criteria SUBCHAPTER FR-5 COUNTRY ENGLISH PLEASURE- SADDLE SEAT FR129 General FR130 Tack FR131 Attire © USEF 2021 FR - 1 FR132 Qualifying Gaits FR133 Friesian Country English Pleasure Class Specifications SUBCHAPTER FR-6 ENGLISH PLEASURE—HUNT SEAT FR134 General FR135 Tack FR136 Attire FR137 Qualifying Gaits FR138 English Pleasure - Hunt Seat Class Specifications SUBCHAPTER FR-7 DRESSAGE FR139 General SUBCHAPTER FR-8 DRESSAGE HACK FR140 General FR141 Tack FR142 Attire FR143 Qualifying Gaits and Class Specifications SUBCHAPTER FR-9 DRESSAGE SUITABILITY FR144 General FR145 Tack FR146 Attire FR147 Qualifying Gaits and Class Specifications SUBCHAPTER -

Culture and Contempt: the Limitations of Expressive Criminal Law

Culture and Contempt: The Limitations of Expressive Criminal Law Ted Sampsell-Jones* The law is the master teacher and guides each generation as to what is acceptable conduct. - Asa Hutchinson' The law of the land in America is full of shit. - Chuck D' I. INTRODUCTION Over the past decade, legal scholars have paid increasing attention to ways that criminal law affects social norms and socialization. While these ideas are not entirely original,1 the renewed focus on criminal law's role in social construction has been illuminating nonetheless. The recent scholarship has reminded us that criminal laws prevent crime not only by applying legal sanctions ' The author received an A.B. from Dartmouth, a J.D. from Yale Law School, and is currently clerking for Judge William Fletcher on the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. Thanks to Michelle Drake, Bob Ellickson, Elizabeth Emens, Owen Fiss, David Fontana, Bernard Harcourt, Neal Katyal, Heather Lewis, Richard McAdams, Brian Nelson, and Sara Sampsell-Jones for their suggestions and comments. Asa Hutchinson, Administrator, U.S. Drug Enforcement Admin., Debate with Gov. Gary Johnson (N.M.) at the Yale Law School (Nov. 15, 2001), available at http://www.usdoj.gov/dea/speeches/sl 11501.html. 'CHUCK D, FIGHT THE POWER: RAP, RACE, AND REALITY 14 (1997). 1. See Mark Tushnet, Everything Old Is New Again, 1998 WISC. L. REV. 579. By tracing the ideological development of the "new" school of criminal law scholarship, Bernard Harcourt has questioned its originality. BERNARD E. HARCOURT, ILLUSION OF ORDER: THE FALSE PROMISE OF BROKEN WINDOWS POLICING 1-16, 24-56 (2001). -

An Examination of Essential Popular Music Compact Disc Holdings at the Cleveland Public Library

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 435 403 IR 057 553 AUTHOR Halliday, Blane TITLE An Examination of Essential Popular Music Compact Disc Holdings at the Cleveland Public Library. PUB DATE 1999-05-00 NOTE 94p.; Master's Research Paper, Kent State University. Information Science. Appendices may not reproduce adequately. PUB TYPE Dissertations/Theses (040) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Audiodisks; Discographies; *Library Collection Development; *Library Collections; *Optical Disks; *Popular Music; *Public Libraries; Research Libraries; Tables (Data) IDENTIFIERS *Cleveland Public Library OH ABSTRACT In the 1970s and early 1980s, a few library researchers and scholars made a case for the importance of public libraries' acquisition of popular music, particularly rock music sound recordings. Their arguments were based on the anticipated historical and cultural importance of obtaining and maintaining a collection of these materials. Little new research in this direction has been performed since then. The question arose as to what, if anything, has changed since this time. This question was answered by examining the compact disc holdings of the Cleveland Public Library, a major research-oriented facility. This examination was accomplished using three discographies of essential rock music titles, as well as recent "Billboard" Top 200 Album charts. The results indicated a strong orientation toward the acquisition of recent releases, with the "Billboard" charts showing the largest percentages of holdings for the system. Meanwhile, the holdings vis-a-vis the essential discographies ran directly opposite the "Billboard" holdings. This implies a program of short-term patron satisfaction by providing current "hits," while disregarding the long-term benefits of a collection based on demonstrated artistic relevance. -

"Now I Ain't Sayin' She's a Gold Digger": African American Femininities in Rap Music Lyrics Jennifer M

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 "Now I Ain't Sayin' She's a Gold Digger": African American Femininities in Rap Music Lyrics Jennifer M. Pemberton Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES “NOW I AIN’T SAYIN’ SHE’S A GOLD DIGGER”: AFRICAN AMERICAN FEMININITIES IN RAP MUSIC LYRICS By Jennifer M. Pemberton A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Sociology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Jennifer M. Pemberton defended on March 18, 2008. ______________________________ Patricia Yancey Martin Professor Directing Dissertation ______________________________ Dennis Moore Outside Committee Member ______________________________ Jill Quadagno Committee Member ______________________________ Irene Padavic Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Irene Padavic, Chair, Department of Sociology ___________________________________ David Rasmussen, Dean, College of Social Sciences The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii For my mother, Debra Gore, whose tireless and often thankless dedication to the primary education of children who many in our society have already written off inspires me in ways that she will never know. Thank you for teaching me the importance of education, dedication, and compassion. For my father, Jeffrey Pemberton, whose long and difficult struggle with an unforgiving and cruel disease has helped me to overcome fear of uncertainty and pain. Thank you for instilling in me strength, courage, resilience, and fortitude. -

Download Free Music Master P Ghetto Dope Download Free Music Master P Ghetto Dope

download free music master p ghetto dope Download free music master p ghetto dope. © 2021 Rhapsody International Inc., a subsidiary of Napster Group PLC. All rights reserved. Napster and the Napster logo are registered trademarks of Rhapsody International Inc. Napster. Music Apps & Devices Blog Pricing Artist & Labels. About Us. Company Info Careers Developers. Resources. Account Customer Support Redeem Coupon Buy a Gift. Legal. Terms of Use Privacy Policy End User Agreement. © 2021 Rhapsody International Inc., a subsidiary of Napster Group PLC. All rights reserved. Napster and the Napster logo are registered trademarks of Rhapsody International Inc. Ghetto D Lyrics. [Featuring C Murder Silkk The Shocker] Water bubbling Voice in background repeating "make crack like this" Masta P Imagine substitutin crack for music I mean dope tapes This is how we would make it. (There it is right there) For all you playas hustlaz ballas and even you smokas Ma ma ma ma make crack like this Masta P Ghetto Dope No Limit Records (Ma ma ma make crack like this) Part of the Tobacco Firearms, and Freedom of Speech Committee. Thank you dope fiends for your support. Ha ha. (Beat starts) C Murder Let me give a shot out to the D Boys (drug dealas) Neighborhood dope man I mean real niggas Thata make a dolla out a fifteen cents Ain't got a dime, but I rides and pay the rent Professional crackslanger I serve fiends I once went to jail for having rocks up in my jeans But nowadays I be too smart for the Taz C Murder been known to keep the rocks up in the skillet man Waitin on a kilo they eight I'm straight you dig What you need ten Ain't no fuckin order too big And makin crack like this is the song You won't be getting yo money if yo shit ain't cooked long Never cook yo dope it might come out brown Them fiends gonna run yo ass clean outa town But fuck that I'm bout to put my soldias in the game And tell ya how to make crack from cocaine. -

Virus 23, 1989

Contents Replicating New Strains Page 4 Jonathan Levine Interview By Bruce Fletcher Page 5 . ,A Toxic G,uide .from Greenpeace Page 15 Brain machines By Belinda Atkinson Page 22 William Gibson biography By Tom Maddox Page 24 ZING, ZANG A Comic from Brad Lambert Page 26 William Gibson Interview By Darren Wershler Henry Page 28 The Two Sides of Tom Maddox By Bruce Fletcher Page 36 Now I Lay Me .. Down To Sleep Fiction by Bruce Fletcher Page 40 Molester A poem by Yassin 80ga Page 44 Frank Ogden: Laws of the Future Page 45 Television Magick By T. o. P.Y. U.S. Page 48 The A.D.'o.S.A. recommends Page 58 Clippings Page 64 Virus 23, 1989. C\O BOX 46 G)Share-Right 1989 RED DEER, ALBERTA, You may reproduce this material if your recipients may also reproduce it. CANADA. T4N 5E7. Front cover: Video-Head - Donald David. PAGE4 VIRUS 23, ISSUE 0 eplicating new Reality begins with the human mind. The human nervous system filters, categorizes and distorts the external universe until the individual can truly be said to create the world in which they live. The process of enculturation by itself usually creates the reality in which most people live. Thought is imposed by the cultural environment. Values, beliefs and even behavioral paradigms are detcnnincd by the social status quo. People live in a shared illusory reality, a consensual hallucination, without realizing its true nature, thereby abscond ing themselves of all personal responsibility. They believe they know truth. Individuals have the potent.ial to control these illusions, foster individual thought and promote rapid changes within the existing socio-cultural mileau. -

Collection 2013

Collection 2013 EXPERIENCE THE QUALITY A passion for perfection The Mercedes-Benz Collection 2013 is the result of an uncompromising approach to design and development and selection of the highest quality materials. The products you will find in this brochure are specially manufactured for Mercedes-Benz in collaboration with renowned partners. For all the diversity our Collection has to offer, there is one thing you will find on every page and in every detail: Mercedes-Benz’s passion for perfect design, resulting in both timeless classics and products that capture the current zeitgeist. We hope you enjoy exploring the Mercedes-Benz Collection 2013 – browse through the Collection in this brochure or visit your Mercedes-Benz partner. 3 CONTENTS 7 WATCHES 21 FASHION Men page 22 | Women page 39 | Caps page 43 47 ACCESSORIES Sunglasses page 48 | Pens page 51 | Other personal accessories page 53 57 TRAVEL Luggage, bags & rucksacks page 58 | Leather goods & handbags page 68 | Umbrellas page 81 85 KEY RINGS 97 GIFT IDEAS Gift items page 98 | Motorsports page 111 | Trucker page 112 | Children page 117 123 SPORT Bikes page 124 | Golf page 130 | Motorsports page 133 139 MODEL CARS 147 AMG Fashion page 148 | Leather goods page 154 | Luggage & umbrellas page 160 | AMG Retro Edition page 162 5 WATCHES | BUSINESS STYLE CHRONOGRAPH WATCH | page 8 | WOMEN’S FUNKY ELEGANCE WATCH | page 18 | NAIL POLISH SET page 105 7 1 2 3 BUSINESS STYLE CHRONOGRAPH WATCH Stainless steel case. Swiss made. Ronda 5030.D quartz movement with chronograph function. Mineral crystal with magnifying window. Water-resistant to 10 ATM. -

2020-21 Officials Guidebook

2020-21 OFFICIALS GUIDEBOOK Officials at an interscholastic athletic event are participants in the educational development of high school students. As such, they must exercise a high level of self-discipline, independence and responsibility. The purpose of this Code is to establish guidelines for ethical standards of conduct for all interscholastic officials. Officials shall master both the rules of the game and the mechanics necessary to enforce the rules and shall exercise authority in an impartial, firm and controlled manner. Officials shall work with each other and their state associations in a constructive and cooperative manner. Officials shall uphold the honor and dignity of the profession in all interaction with student-athletes, coaches, athletic directors, school administrators, colleagues and the public. Officials shall prepare themselves both physically and mentally, shall dress neatly and appropriately and shall comport themselves in a manner consistent with the high standards of the profession. Officials shall be punctual and professional in the fulfillment of all contractual obligations. Officials shall remain mindful that their conduct influences the respect that student-athletes, coaches and the public hold for the profession. Officials shall, while enforcing the rules of play, remain aware of the inherent risk of injury that competition poses to student-athletes. Where appropriate, they shall inform event management of conditions or situations that appear unreasonably hazardous. Officials shall take reasonable steps -

İncəsənət Və Mədəniyyət Problemləri Jurnalı

AZƏRBAYCAN MİLLİ ELMLƏR AKADEMİYASI AZERBAIJAN NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES НАЦИОНАЛЬНАЯ АКАДЕМИЯ НАУК АЗЕРБАЙДЖАНА MEMARLIQ VƏ İNCƏSƏNƏT İNSTİTUTU INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTURE AND ART ИНСТИТУТ АРХИТЕКТУРЫ И ИСКУССТВА İncəsənət və mədəniyyət problemləri Beynəlxalq Elmi Jurnal N 1 (71) Problems of Arts and Culture International scientific journal Проблемы искусства и культуры Международный научный журнал Bakı - 2020 Baş redaktor: ƏRTEGİN SALAMZADƏ, AMEA-nın müxbir üzvü (Azərbaycan) Baş redaktorun müavini: GULNARA ABDRASİLOVA, memarlıq doktoru, professor (Qazaxıstan) Məsul katib : FƏRİDƏ QULİYEVA, sənətşünaslıq üzrə fəlsəfə doktoru (Azərbaycan) Redaksiya heyətinin üzvləri: ZEMFİRA SƏFƏROVA – AMEA-nın həqiqi üzvü (Azərbaycan) RƏNA MƏMMƏDOVA – AMEA-nın müxbir üzvü (Azərbaycan) RƏNA ABDULLAYEVA – sənətşünaslıq doktoru, professor (Azərbaycan) SEVİL FƏRHADOVA – sənətşünaslıq doktoru, professor (Azərbaycan) RAYİHƏ ƏMƏNZADƏ - memarlıq doktoru, professor (Azərbaycan) VLADİMİR PETROV – fəlsəfə elmləri doktoru, professor (Rusiya) KAMOLA AKİLOVA – sənətşünaslıq doktoru, professor (Özbəkistan) MEYSER KAYA – fəlsəfə doktoru (Türkiyə) VİDADİ QAFAROV – sənətşünaslıq üzrə fəlsəfə doktoru (Azərbaycan) Editor-in-chief: ERTEGIN SALAMZADE, corresponding member of ANAS (Azerbaijan) Deputy editor: GULNARA ABDRASSILOVA, Prof., Dr. (Kazakhstan) Executive secretary: FERİDE GULİYEVA Ph.D. (Azerbaijan) Members to editorial board: ZEMFIRA SAFAROVA – academician of ANAS (Azerbaijan) RANA MAMMADOVA – corresponding-member of ANAS (Azerbaijan) RANA ABDULLAYEVA – Prof., Dr. -

Jonsered Accessory Catalog NEW2

ACCESSORY CATALOG INSIDE Protective Apparel.........................3 - 8 ESSENTIAL GEAR FOR Helmets, Hearing Protection, Boots, Chaps, and Replacement Parts JONSERED OWNERS Like our highly-regarded power equipment products, Jon- Guide sered accessories are tested and approved in real-world Bars....................................9 conditions, to ensure they meet our standards of quality, Quality Jonsered Bars, ergonomic design, and efficiency. Bar and Chain Kits, Bar Covers Our work clothing and safety gear has been carefully devel- oped to provide the best possible comfort, freedom of Engine and movement, and durability. Bar & Chain Oil................10 Our maintenance tools and other accessories are designed to help you get optimum performance from your Jonsered Jonsered equipment. Cases.................................11 Genuine Jonsered accessories and apparel are available only from your local authorized Jonsered dealer. Filing Please visit www.TiltonEquipment.com to locate your Guides..............................12 nearest authorized Jonsered dealer. Trimmer and Brushcutter Accessories................13 - 16 Heads, Blades, Lubricant & File Kit Jonsered Wear..........................17 - 19 Gloves, Coats, Shirts, Suspenders. Jonsered Headwear..................20 - 21 Caps & Hats Jonsered Gear..................................22 Copyright © 2010 Tilton Equipment Company. All rights reserved. No portion may be reproduced, transmitted, scanned or stored by any means, electronic or mechanical, without the expressed written permission of Literature Tilton Equipment Company. & Videos...........................23 PLEASE NOTE: Items indicated as “NEW” mean they are new to this edition of the Jonsered Accessory Catalog. These products are available exclusively from Authorized Jonsered Dealers. Stocked items may vary by dealer. Some products may need to be ordered. 2 Suggested retail prices are subject to change without notice. PROTECTIVE APPAREL JONSERED PRO HELMET ASSEMBLY High-density polyethylene hard hat.