Donald (Skip) Hays Hits for the Cycle in the Dixie Association

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NCAA Division I Baseball Records

Division I Baseball Records Individual Records .................................................................. 2 Individual Leaders .................................................................. 4 Annual Individual Champions .......................................... 14 Team Records ........................................................................... 22 Team Leaders ............................................................................ 24 Annual Team Champions .................................................... 32 All-Time Winningest Teams ................................................ 38 Collegiate Baseball Division I Final Polls ....................... 42 Baseball America Division I Final Polls ........................... 45 USA Today Baseball Weekly/ESPN/ American Baseball Coaches Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 46 National Collegiate Baseball Writers Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 48 Statistical Trends ...................................................................... 49 No-Hitters and Perfect Games by Year .......................... 50 2 NCAA BASEBALL DIVISION I RECORDS THROUGH 2011 Official NCAA Division I baseball records began Season Career with the 1957 season and are based on informa- 39—Jason Krizan, Dallas Baptist, 2011 (62 games) 346—Jeff Ledbetter, Florida St., 1979-82 (262 games) tion submitted to the NCAA statistics service by Career RUNS BATTED IN PER GAME institutions -

Fastball Fever Is Everywhere August 10 - 11, 2007 Kitchener-Cambridge Host to 61St Annual ISC Championships

DDirt_Aug10-11 8/10/07 10:43 AM Page 2 Volume 3 – Friday - Saturday Fastball Fever is everywhere August 10 - 11, 2007 Kitchener-Cambridge host to 61st annual ISC Championships The thirty-two teams competing this weekend, will be joined Welcome back,good things come in threes... by the 35 ISC II Tournament of Champions squads on A decade ago it was built, the past several years it has been Tuesday and on Thursday, six enthused Under 19 teams will improved and enhanced, and today Peter Hallman Ball Yard tangle in a three-day affair. In total, 73 teams with more than welcomes 32 of the finest fastball teams in North America to 1,300 players and personnel, will call Kitchener and st the 61 annual International Softball Congress World Cambridge home this week The welcome mat is out – Club Team Championship. 2007 tourney chief, Chairman Gemutlichkeit all round! Duncan Matheson and hundreds of volunteers have been working diligently, many on little sleep, the past two weeks in ONTARIO SOFTBALL ICONS TO BE INDUCTED – Two of softball’s most passionate people will be inducted into the anticipation of hosting the most memorable ISC ISC Hall of Fame on Sunday at the Hall of Fame Induction Championship possible. Breakfast (7:30 am at the Delta Hotel). The class of ’07 includes Once again, the weather gods are smiling favorably and it Kitchener own Larry Lynch, a 30-year veteran of senior fastball, appears that the next nine days will be blessed with an and the late Lloyd Simpson, the ISC pioneer who introduced “the abundance of sunshine (up go the suds sales) to provide the show” to Ontario in the 1970’s. -

By Paul M. Sommers Christopher J. Teves Joseph T. Burchenal And

A POISSON MODEL FOR “HITTING FOR THE CYCLE” IN MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL by Paul M. Sommers Christopher J. Teves Joseph T. Burchenal And Daniel M. Haluska March 2010 MIDDLEBURY COLLEGE ECONOMICS DISCUSSION PAPER NO. 10-11 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS MIDDLEBURY COLLEGE MIDDLEBURY, VERMONT 05753 http://www.middlebury.edu/~econ 2 A POISSON MODEL FOR “HITTING FOR THE CYCLE” IN MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL by Christopher J. Teves Joseph T. Burchenal Daniel M. Haluska Paul M. Sommers Department of Economics Middlebury College Middlebury, Vermont 05753 [email protected] 3 A POISSON MODEL FOR “HITTING FOR THE CYCLE” IN MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL In a recent article in this journal [1], Campbell et al. showed that the Poisson probability distribution provides an excellent fit to the data on no-hit games in Major League Baseball, especially during the period 1920-1959. Hitting for the cycle (that is, when a batter hits a single, double, triple and home run in the same game) is another rare event in Major League Baseball.1,2 And, here too, the Poisson probability distribution given by e −μ μ x p(X = x) = , x = 0, 1, 2, … x! where x denotes the number of ballplayers who “hit for the cycle” (hereafter a “cycle”) in a given season provides a remarkably good fit. The number of cycles by league from 1901 through 2007 are shown in Table 1 (see http://mlb.mlb.com/mlb/history/rare_feats/index.jsp?feature=hit_for_cycle ). Bob Meusel of the New York Yankees hit for the cycle three times in his career (1921, 1922, and 1928). -

Base Ball En Ban B

,,. , Vol. 57-No. 2 Philadelphia, March 18, 1911 Price 5 Cents President Johnson, of the American League, in an Open Letter to the Press, Tells of Twentieth Century Advance of the National Game, and the Chief Factors in That Wonderful Progress and Expansion. SPECIAL TO "SPORTING LIFE." race and the same collection of players in an HICAGO, 111., March 13. President exhibition event in attracting base ball en Ban B. Johnson, of the American thusiasts. An instance in 1910 will serve to League, is once more on duty in illustrate the point I make. At the close C the Fisher Building, following the of the American League race last Fall a funeral of his venerable father. While in Cincinnati President John team composed of Cobb, the champion bats son held a conference with Chair man of the year; Walsh, Speaker, White, man Herrmann, of the National Commission, Stahl, and the pick of the Washington Club, relative to action that should be taken to under Manager McAleer©s direction, engaged prevent Kentucky bookmakers from making in a series with the champion Athletics at a slate on American and National League Philadelphia during the week preceding the pennant races. The upshot is stated as fol opening game of the World©s Series. The lows by President Johnson: ©©There is no attendance, while remunerative, was not as need for our acting, for the newspapers vir large as that team of stars would have at tually have killed the plan with their criti tracted had it represented Washington in the cism.- If the promoters of the gambling syn American League. -

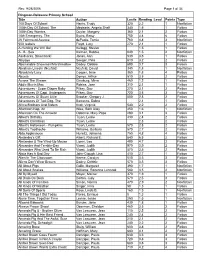

Rev. 9/28/2006 Page 1 of 34 Title Author Lexile Reading Level Points

Rev. 9/28/2006 Page 1 of 34 Dingman-Delaware Primary School Title Author Lexile Reading Level Points Type 100 Days Of School Harris, Trudy 320 2.2 1 Nonfiction 100th Day Of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 340 1.5 1 Fiction 100th Day Worries Cuyler, Margery 360 2.1 2 Fiction 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 750 4.4 6 Fiction 26 Fairmount Avenue dePaola, Tomie 760 4.8 3 Nonfiction 500 Isabels Floyd, Lucy 270 2.1 1 Fiction A-Hunting We Will Go! Kellogg, Steven 1.5 1 Fiction A...B...Sea Kalman, Bobbie 640 1.5 2 Nonfiction Aardvarks, Disembark! Jonas, Ann 530 3.5 1 Fiction Abiyoyo Seeger, Pete 610 3.2 2 Fiction Abominable Snowman/Marshmallow Dadey, Debbie 690 3.7 3 Fiction Abraham Lincoln (Neufeld) Neufeld, David 340 1.8 1 Nonfiction Absolutely Lucy Cooper, Ilene 360 1.8 4 Fiction Abuela Dorros, Arthur 510 3.5 2 Fiction Across The Stream Ginsburg, Mirra 460 1.2 1 Fiction Addie Meets Max Robins, Joan 310 2.1 1 Fiction Adventures - Super Diaper Baby Pilkey, Dav 270 3.1 2 Fiction Adventures Of Capt. Underpants Pilkey, Dav 720 3.5 3 Fiction Adventures Of Stuart Little Brooker, Gregory J. 500 2.8 2 Fiction Adventures Of Taxi Dog, The Barracca, Debra 2.1 1 Fiction Africa Brothers And Sisters Kroll, Virginia 540 2.2 2 Fiction Afternoon Nap, An Wise, Beth Alley 450 1.6 1 Nonfiction Afternoon On The Amazon Osborne, Mary Pope 290 3.1 3 Fiction Albert's Birthday Tryon, Leslie 430 2.4 2 Fiction Albert's Christmas Tryon, Leslie 2.3 2 Fiction Albert's Halloween - Pumpkins Tryon, Leslie 570 2.8 2 Fiction Albert's Toothache Williams, Barbara 570 2.7 2 Fiction Aldo Applesauce Hurwitz, Johanna 750 4.8 4 Fiction Alejandro's Gift Albert, Richard E. -

Message Outline Baseball and the Bible: Hitting for the Cycle 2 Kings 2

Message Outline 2 Kings 2 NIV Baseball and the Bible: 1 When the Lord was about to take Elijah up to heaven in a Hitting for the Cycle whirlwind, Elijah and Elisha were on their way from 2 2 Kings 2 Gilgal. Elijah said to Elisha, “Stay here; the Lord has sent me to Bethel.” Intro: Biblical lessons from baseball… But Elisha said, “As surely as the Lord lives and as you live, I • Last week, the time element of baseball… will not leave you.” So they went down to Bethel. 3 The company of the prophets at Bethel came out to Elisha and • This week a “super cycle” story in Scripture. asked, “Do you know that the Lord is going to take your master from you today?” v.1a—Elijah’s interesting personality in Scripture. “Yes, I know,” Elisha replied, “so be quiet.” 4 Then Elijah said to him, “Stay here, Elisha; the Lord has sent me v.1—A double due of mentor/mentee to Jericho.” (Elijah/Elisha)… And he replied, “As surely as the Lord lives and as you live, I will • A farewell walk to remember… not leave you.” So they went to Jericho. 5 The company of the prophets at Jericho went up to Elisha and v.2-6—Triple cities of significance… asked him, “Do you know that the Lord is going to take your v.7-8—A single hit to divide the waters… master from you today?” v.9-10—A double portion… “Yes, I know,” he replied, “so be quiet.” 6 Then Elijah said to him, “Stay here; the Lord has sent me to the v.11-12—A heavenly home run in walk off Jordan.” fashion! And he replied, “As surely as the Lord lives and as you live, I will v.13-18—Evidences of what Elisha inherited.. -

March-6-2020-Digital

Collegiate Baseball The Voice Of Amateur Baseball Started In 1958 At The Request Of Our Nation’s Baseball Coaches Vol. 63, No. 5 Friday, March 6, 2020 $4.00 Baseball’s Greatest Story Simply Amazing Given no chance called 11 World Series. was for all the men and women who O’Leary spent five months in showed up every single day for a of living after 100% of the hospital, underwent dozens of cause bigger than themselves. John O’Leary’s body surgeries, lost all of his fingers to “My dad sets the champagne in was burned, Cardinals’ amputation and relearned to walk, the corner and then walks over to me, write and feed himself. puts his hand on my leg and looks at announcer Jack Buck “Thirty-three years ago, I was by me squarely in the eyes, “John, little springs into action. myself in a burn center room in a man. You did it.’ I looked up at my wheelchair,” said O’Leary. dad and said, ‘Yes I did!’ By LOU PAVLOVICH, JR. “It was a room I knew well because “I look back at that experience Editor/Collegiate Baseball I had been in it for the previous five 33 years ago realizing how little I months. After spending five months really did. ASHVILLE, Tenn. — The anywhere, you are ready to go home. “Sometimes it’s easy to get stuck greatest baseball story My dad was down the hall speaking in the rut and be beaten down by life. Never told took place at the to a nurse. -

Rocky Mountain Classical Christian Schools Speech Meet Official Selections

Rocky Mountain Classical Christian Schools Speech Meet Official Selections Sixth Grade Sixth Grade: Poetry 3 anyone lived in a pretty how town 3 At Breakfast Time 5 The Ballad of William Sycamore 6 The Bells 8 Beowulf, an excerpt 11 The Blind Men and the Elephant 14 The Builders 15 Casey at the Bat 16 Castor Oil 18 The Charge of the Light Brigade 19 The Children’s Hour 20 Christ and the Little Ones 21 Columbus 22 The Country Mouse and the City Mouse 23 The Cross Was His Own 25 Daniel Boone 26 The Destruction of Sennacherib 27 The Dreams 28 Drop a Pebble in the Water 29 The Dying Father 30 Excelsior 32 Father William (also known as The Old Man's Complaints. And how he gained them.) 33 Hiawatha’s Childhood 34 The House with Nobody in It 36 How Do You Tackle Your Work? 37 The Fish 38 I Hear America Singing 39 If 39 If Jesus Came to Your House 40 In Times Like These 41 The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers 42 Live Christmas Every Day 43 The Lost Purse 44 Ma and the Auto 45 Mending Wall 46 Mother’s Glasses 48 Mother’s Ugly Hands 49 The Naming Of Cats 50 Nathan Hale 51 On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer 53 Partridge Time 54 Peace Hymn of the Republic 55 Problem Child 56 A Psalm of Life 57 The Real Successes 60 Rereading Frost 62 The Sandpiper 63 Sheridan’s Ride 64 The Singer’s Revenge 66 Solitude 67 Song 68 Sonnet XVIII 69 Sonnet XIX 70 Sonnet XXX 71 Sonnet XXXVI 72 Sonnet CXVI 73 Sonnet CXXXVIII 74 The Spider and the Fly 75 Spring (from In Memoriam) 77 The Star-Spangled Banner 79 The Story of Albrecht Dürer 80 Thanksgiving 82 The Touch of the -

Teaching Skills with Children's Literature As Mentor Text Presented at TLA 2012

Teaching Skills with Children's Literature as Mentor Text Presented at TLA 2012 List compiled by: Michelle Faught, Aldine ISD, Sheri McDonald, Conroe ISD, Sally Rasch, Aldine ISD, Jessica Scheller, Aldine ISD. April 2012 2 Enhancing the Curriculum with Children’s Literature Children’s literature is valuable in the classroom for numerous instructional purposes across grade levels and subject areas. The purpose of this bibliography is to assist educators in selecting books for students or teachers that meet a variety of curriculum needs. In creating this handout, book titles have been listed under a skill category most representative of the picture book’s story line and the author’s strengths. Many times books will meet the requirements of additional objectives of subject areas. Summaries have been included to describe the stories, and often were taken directly from the CIP information. Please note that you may find some of these titles out of print or difficult to locate. The handout is a guide that will hopefully help all libraries/schools with current and/or dated collections. To assist in your lesson planning, a subjective rating system was given for each book: “A” for all ages, “Y for younger students, and “O” for older students. Choose books from the list that you will feel comfortable reading to your students. Remember that not every story time needs to be a teachable moment, so you may choose to use some of the books listed for pure enjoyment. The benefits of using children’s picture books in the instructional setting are endless. The interesting formats of children’s picture books can be an excellent source of information, help students to understand vocabulary words in different contest areas, motivate students to learn, and provide models for research and writing. -

2016 Altoona Curve Final Notes

EASTERN LEAGUE CHAMPIONS DIVISION CHAMPIONS PLAYOFF APPEARANCES PLAYERS TO MLB 2010 2004, 2010 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 137 2010, 2015, 2016 THE 18TH SEASON OF CURVE BASEBALL: The Curve finished the season 12 games over .500 and a half-game 2016 E.L. WESTERN STANDINGS behind Akron in the Western Division, clinching a wild card berth with a 2-0, ten-inning win over Richmond in the Team W-L PCT GB regular-season finale on September 5. 2016 marked the first time the Curve have made back-to-back postseasons Akron 77-64 .546 -- since going to four straight from 2003-2006, the first four playoff appearances in team history. Altoona took over first Altoona 76-64 .543 0.5 place in the Western Division for the first time on June 26, and held that spot for 55 of 63 games until Akron took it Harrisburg 76-66 .535 1.5 on the next-to-last day of the season. Richmond 62-79 .440 15.0 Erie 62-79 .440 15.0 IN THE PLAYOFFS: 2016 marked the seventh postseason appearance in Altoona franchise history and the fifth as a Bowie 56-86 .394 21.5 wild card qualifier. The Curve faced Akron in the Division Series for the fourth time, and have dropped all four series. In Game 1, the Curve held a 5-1 lead through two innings and led by a 7-3 score through six innings before Akron E.L. WESTERN DIVISION SERIES scored six runs in the seventh and won, 12-8. In Game 2, Erich Weiss and Barrett Barnes each drove in a run in the Date Opp. -

Clyde Pharr, the Women of Vanderbilt, and the Wyoming Judge: the Story Behind the Translation of the Theodosian Code in Mid- Century America

Clyde Pharr, the Women of Vanderbilt, and the Wyoming Judge: The Story behind the Translation of the Theodosian Code in Mid- Century America Linda Jones Hall* Abstract — When Clyde Pharr published his massive English translation of the Theodosian Code with Princeton University Press in 1952, two former graduate students at Vanderbilt Uni- versity were acknowledged as co-editors: Theresa Sherrer David- son as Associate Editor and Mary Brown Pharr, Clyde Pharr’s wife, as Assistant Editor. Many other students were involved. This article lays out the role of those students, predominantly women, whose homework assignments, theses, and dissertations provided working drafts for the final volume. Pharr relied heavily * Professor of History, Late Antiquity, St. Mary’s College of Mary- land, St. Mary’s City, Maryland, USA. Acknowledgements follow. Portions of the following items are reproduced by permission and further reproduction is prohibited without the permission of the respective rights holders. The 1949 memorandum and diary of Donald Davidson: © Mary Bell Kirkpatrick. The letters of Chancellor Kirkland to W. L. Fleming and Clyde Pharr; the letter of Chancellor Branscomb to Mrs. Donald Davidson: © Special Collections and University Archives, Jean and Alexander Heard Library, Vanderbilt University. The following items are used by permission. The letters of Clyde Pharr to Dean W. L. Fleming and Chancellor Kirkland; the letter of A. B. Benedict to Chancellor O. C. Carmichael: property of Special Collections and University Archives, Jean and Alexander -

Revisiting Mildred Haun's Genre and Literary Craft

From the Margins: Revisiting Mildred Haun’s Genre and Literary Craft By Clarke Sheldon Martin Honors Thesis Department of English and Comparative Literature University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill 2017 Approved: ____________________________________________ 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank Professor Irons for her investment this project and in me. I would also like to thank Professor Gwin and Professor McFee for sitting on this committee and for their time and support. I am honored to have received funding from the Department of English and Comparative Literature to present Section IV of this paper at the Mildred Haun Conference in Morristown, Tennessee. Additionally, research for this project was supported by the Tom and Elizabeth Long Excellence Fund for Honors administered by Honors Carolina. Two fantastic librarians made my research for this paper a wonderful experience. Many thanks to Tommy Nixon at UNC Chapel Hill and Molly Dohrmann at Vanderbilt University. Lastly, I want to thank my parents Matthew and Catherine for their encouragement and enthusiasm during my time at Carolina and for their constant love. 3 I Mildred Haun burst onto the Appalachian literary scene when her 1940 book, The Hawk’s Done Gone, was published. The work, a collection of ten stories, offers an in-depth and instructional catalogue of Haun’s native east Tennessee mountain culture through the voice of Mary Dorthula Kanipe, a respected granny-woman trapped in a patriarchal social structure. The Hawk’s Done Gone enjoyed favorable reviews at its time of publication, but it quickly slipped into obscurity. Haun’s short life and complicated relationship with her publisher may have pushed her voice into the margins during her time, but The Hawk’s Done Gone provides cultural observation and connection to a way of life and oral tradition that is deserving of attention today.