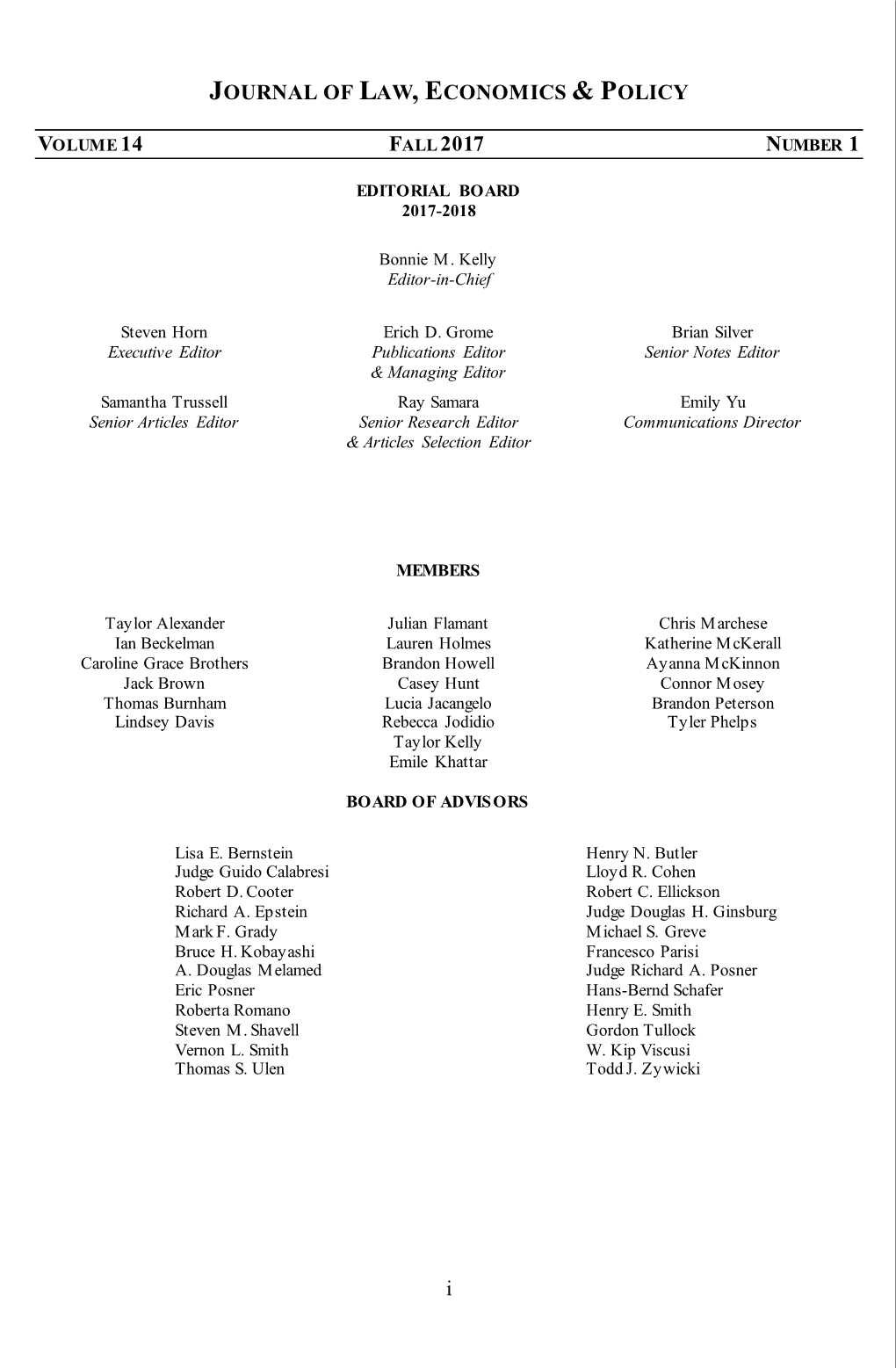

I JOURNAL of LAW, ECONOMICS & POLICY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OFFICE HOURS: Monday - Friday, 8:00 A.M

LAFAYETTE COUNTY COURTHOUSE 626 Main Street Darlington, Wisconsin 53530 608-776-4856 OFFICE HOURS: Monday - Friday, 8:00 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. Chairman ................................... Jack Sauer 1st Vice Chairman ............... Gerald Heimann 2nd Vice Chairman ................... Tony Ruesga County Clerk .................. Carla M. Jacobson Chief Deputy County Clerk... Laurie Monson 1 2019 INVOICE One complimentary copy of the Official Directory can be picked up at the County Clerk=s Office. This booklet is provided free of charge to Local Government Agencies and Lafayette County residents. There is a $1.50 charge for each directory mailed to cover the cost of printing, shipping and handling. Remit to: Lafayette County Clerk 626 Main Street Darlington, WI 53530 2 OFFICIAL DIRECTORY INDEX COUNTY ACTIVITIES AND FESTIVITIES ......... 5 POPULATION AND EQUALIZED VALUE .......... 7 COURTHOUSE DIRECTORY ............................ 9 FEDERAL GOVERNMENT ................................ 11 STATE GOVERNMENT .................................... 13 COUNTY OFFICERS AND EMPLOYEES ......... 17 LAFAYETTE COUNTY SUPERVISORY DISTRICTS ....................................................... 27 LAFAYETTE COUNTY BOARD OF SUPERVISORS ................................................. 29 COMMITTEES ................................................... 32 LAFAYETTE COUNTY BAR .............................. 39 FAMILY & COURT COMMISSIONERS ............. 40 TOWN, VILLAGE, AND CITY OFFICERS ......... 41 SCHOOL DISTRICTS & TECHNICAL COLLEGES ................................. -

Elections Coming! Get Ready to Vote! Important Tips for Voters

Elections coming! Important Tips for Voters City of Milwaukee Most people need a photo ID to vote. Ward 35 February 20, 2018 – Spring Primary A WI driver’s license or state ID is easiest. Learn if your college ID is OK, Top two winners for each office go on to how to get a free state ID at the DMV Save this the April election. (No parties are listed.) and more at bringit.wi.gov. The Milw. info ● WI Supreme Court Justice Co. Register of Deeds will give you a ● WI Court of Appeals Judge free birth certificate (to get a free ID) ● Milwaukee County Supervisor if you have never had a license or ● Milwaukee County Circuit Judges state ID (any state) and were born in (Judges will be elected for 10 branches, and now live in Milwaukee County. with terms beginning August 1) If you have trouble getting to the polls April 3, 2018 – Spring General Election because of age, illness, or disability, For each office, the candidate with the you can apply for absentee ballots as most votes wins. an indefinitely confined voter and Vote at you will not need to have ID. Contact Parkview School __________________________ City Hall for more info at 414-286-3491. 10825 W Villard Ave If you move less than 10 days before August 14, 2018 – Fall Primary the election you must vote at your old WI address, in person or absentee. ● US Senator You can ● US Congress Member vote on If you have a current valid WI driver’s Vote at River Trail School ● Governor only one license/state ID you can register to ● Lieutenant Governor party’s list. -

2019 Guide to the Wisconsin Supreme Court and Judicial Evaluation Fourth Edition: 2018-19 Term

2019 Guide to the Wisconsin Supreme Court and Judicial Evaluation Fourth Edition: 2018-19 Term November 2019 2019 GUIDE TO THE WISCONSIN SUPREME COURT AND JUDICIAL EVALUATION Prepared By: Paige Scobee, Hamilton Consulting Group, LLC November 2019 The Wisconsin Civil Justice Council, Inc. (WCJC) was formed in 2009 to represent Wisconsin business inter- ests on civil litigation issues before the legislature and courts. WCJC’s mission is to promote fairness and equi- ty in Wisconsin’s civil justice system, with the ultimate goal of making Wisconsin a better place to work and live. The WCJC board is proud to present its fourth Guide to the Wisconsin Supreme Court and Judicial Evalua- tion. The purpose of this publication is to educate WCJC’s board members and the public about the role of the Supreme Court in Wisconsin’s business climate by providing a summary of the most important decisions is- sued by the Wisconsin Supreme Court affecting the Wisconsin business community. Board Members Bill G. Smith Jason Culotta Neal Kedzie National Federation of Independent Midwest Food Products Wisconsin Motor Carriers Business, Wisconsin Chapter Association Association Scott Manley William Sepic Matthew Hauser Wisconsin Manufacturers & Wisconsin Automobile & Truck Wisconsin Petroleum Marketers & Commerce Dealers Association Convenience Store Association Andrew Franken John Holevoet Kristine Hillmer Wisconsin Insurance Alliance Wisconsin Dairy Business Wisconsin Restaurant Association Association Brad Boycks Wisconsin Builders Association Brian Doudna Wisconsin Economic Development John Mielke Association Associated Builders & Contractors Eric Borgerding Gary Manke Wisconsin Hospital Association Midwest Equipment Dealers Association 10 East Doty Street · Suite 500 · Madison, WI 53703 www.wisciviljusticecouncil.org · 608-258-9506 WCJC 2019 Guide to the Wisconsin Supreme Court Page 2 and Judicial Evaluation Executive Summary The Wisconsin Supreme Court issues decisions that have a direct effect on Wisconsin businesses and individu- als. -

2015-2016 Wisconsin Blue Book: Chapter 7

Judicial 7 Branch The judicial branch: profile of the judicial branch, summary of recent significant supreme court decisions, and descriptions of the supreme court, court system, and judicial service agencies Cassius Fairchild (Wisconsin Veterans Museum) 558 WISCONSIN BLUE BOOK 2015 – 2016 WISCONSIN SUPREME COURT Current Term First Assumed Began First Expires Justice Office Elected Term July 31 Shirley S. Abrahamson. 1976* August 1979 2019 Ann Walsh Bradley . 1995 August 1995 2015** N. Patrick Crooks . 1996 August 1996 2016 David T. Prosser, Jr. �������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1998* August 2001 2021 Patience Drake Roggensack, Chief Justice . 2003 August 2003 2023 Annette K. Ziegler . 2007 August 2007 2017 Michael J. Gableman . 2008 August 2008 2018 *Initially appointed by the governor. **Justice Bradley was reelected to a new term beginning August 1, 2015, and expiring July 31, 2025. Seated, from left to right are Justice Annette K. Ziegler, Justice N. Patrick Crooks, Justice Shirley S. Abrahamson, Chief Justice Patience D. Roggensack, Justice Ann Walsh Bradley, Justice David T. Prosser, Jr., and Justice Michael J. Gableman. (Wisconsin Supreme Court) 559 JUDICIAL BRANCH A PROFILE OF THE JUDICIAL BRANCH Introducing the Court System. The judicial branch and its system of various courts may ap- pear very complex to the nonlawyer. It is well-known that the courts are required to try persons accused of violating criminal law and that conviction in the trial court may result in punishment by fine or imprisonment or both. The courts also decide civil matters between private citizens, ranging from landlord-tenant disputes to adjudication of corporate liability involving many mil- lions of dollars and months of costly litigation. -

Journal of Media Law & Ethics

UNIVERSITY OF BALTIMORE SCHOOL OF LAW JOURNAL OF MEDIA LAW & ETHICS Editor ERIC B. EASTON, PROFESSOR EMERITUS University of Baltimore School of Law EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS BENJAMIN BENNETT-CARPENTER, Special Lecturer, Oakland Univ. (Michigan) STUART BROTMAN, Distinguished Professor of Media Management & Law, Univ. of Tennessee L. SUSAN CARTER, Professor Emeritus, Michigan State University ANTHONY FARGO, Associate Professor, Indiana University AMY GAJDA, Professor of Law, Tulane University STEVEN MICHAEL HALLOCK, Professor of Journalism, Point Park University MARTIN E. HALSTUK, Professor Emeritus, Pennsylvania State University CHRISTOPHER HANSON, Associate Professor, University of Maryland ELLIOT KING, Professor, Loyola University Maryland JANE KIRTLEY, Silha Professor of Media Ethics & Law, University of Minnesota NORMAN P. LEWIS, Associate Professor, University of Florida KAREN M. MARKIN, Dir. of Research Development, University of Rhode Island KIRSTEN MOGENSEN, Associate Professor, Roskilde University (Denmark) KATHLEEN K. OLSON, Professor, Lehigh University RICHARD J. PELTZ-STEELE, Chancellor Professor, Univ. of Mass. School of Law JAMES LYNN STEWART, Professor, Nicholls State University CHRISTOPHER R. TERRY, Assistant Professor, University of Minnesota DOREEN WEISENHAUS, Associate Professor, Northwestern University University of Baltimore Journal of Media Law & Ethics, Vol. 9 No. 1 (Spring/Summer 2021) 1 Submissions The University of Baltimore Journal of Media Law & Ethics (ISSN1940-9389) is an on-line, peer- reviewed journal published quarterly by the University of Baltimore School of Law. JMLE seeks theoretical and analytical manuscripts that advance the understanding of media law and ethics in society. Submissions may have a legal, historical, or social science orientation, but must focus on media law or ethics. All theoretical perspectives are welcome. All manuscripts undergo blind peer review. -

June Case Law Update Wisconsin Supreme Court Opinions

For more questions or comments about these cases, please contact: Brian W. Ohm, JD Dept. of Planning and Landscape Architecture, UW-Madison/Extension 925 Bascom Mall Madison, WI 53706 [email protected] June Case Law Update June 30, 2018 A summary of Wisconsin court opinions decided during the month of June related to planning For previous Case Law Updates, please go to: www.wisconsinplanners.org/learn/law-and-legislation Wisconsin Supreme Court Opinions Vested Rights Extends to All Land Identified in a Building Permit Application Golden Sands Dairy LLC v. Town of Saratoga, 2018 WI 61, is the latest court decision in the dispute involving a proposed 6,388 acres dairy operation located primarily in the Town of Saratoga in Wood County. Golden Sands applied for a permit to build seven structures on 92 acres of its proposed 6388-acre operation. At the time of the application, the Town was under county zoning which zoned the land “unrestricted” meaning the land at issue could be used for any purpose. At the time of the application, the Town had completed its comprehensive plan and was in the process of adopting village powers so it could adopt its own zoning ordinance. Two days after Golden Sands applied for the building permit, the Town passed a moratorium on issuing building permits. The Town subsequently adopted a zoning ordinance that was then ratified by the Wood County Board. Under the Town’s zoning ordinance, only two percent of the Town (and none of Golden Sands’ land) was zoned for agricultural use. The Town refused to issue the building permit requested by Golden Sands. -

Petitioner, V

No. __________ In The Supreme Court of the United States ♦ DEBRA K. SANDS, Petitioner, v. JOHN R. MENARD, JR., MENARD THOROUGHBREDS, INC., MENARD, INC., WEBSTER HART AS TRUSTEE OF THE JOHN R. MENARD, JR. 2002 TRUST AND RELATED TRUSTS, ANGELA L. BOWE AS TRUSTEE OF THE JOHN R. MENARD, JR. 2002 TRUST AND RELATED TRUSTS AND ALPHONS PITTERLE AS TRUSTEE OF THE JOHN R. MENARD, JR. 2002 TRUST AND RELATED TRUSTS, Respondents. ♦ On Petition for Writ of Certiorari To The Wisconsin Supreme Court ♦ PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI ♦ Mel C. Orchard, III Daniel R. Shulman THE SPENCE LAW FIRM, LLC Counsel of Record 15 South Jackson Street Richard C. Landon Post Office Box 548 GRAY, PLANT, MOOTY, Jackson, WY 83001 MOOTY & BENNETT, P.A. Telephone: (307) 733-7290 500 IDS Center 80 South Eighth Street Minneapolis, MN 55402 Telephone: 612-632-3000 [email protected] Counsel for Petitioner i QUESTIONS PRESENTED The Fourteenth Amendment prohibits a State from depriving any person of property without due process of law. For more than nine years, the Petitioner in this case, Debra K. Sands, litigated a claim for un- just enrichment against her fiancé, John R. Menard, Jr., reported to be the richest man in Wisconsin and a major contributor to organizations supporting the candidacy of multiple Wisconsin Supreme Court Justices. During those nine years, which never re- sulted in a trial, the sole issue contested by the parties was whether Sands’ claim was barred by a Wisconsin Supreme Court Rule of Professional Responsibility. On December 29, 2017, the Wisconsin Supreme Court, finding for Sands on the ethical issue, nevertheless ruled that Sands’ complaint failed to state a claim for unjust enrichment, an issue never raised, briefed, or previously argued. -

Wisconsin Supreme Court Justices Endorse Judge Paul Bugenhagen Jr

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 19, 2020 Contact: Amy Lunde, [email protected], 701-595-2317 Wisconsin Supreme Court Justices Endorse Judge Paul Bugenhagen Jr MUKWONAGO – Judge Paul Bugenhagen Jr, candidate for Wisconsin Court of Appeals District II, announced the endorsement of Wisconsin Supreme Court Justices Rebecca Bradley, Brian Hagedorn, and Daniel Kelly, as well as former Justices David Prosser and Michael Gableman. “I’m honored to receive the endorsements of Justices Bradley, Hagedorn, Kelly and former justices Prosser and Gableman,” said Judge Bugenhagen. “All five are principled judges who reflect sound temperament and strong commitment to the Constitution at our court’s highest level, and I am grateful for their support.” “Our appellate courts make critical decisions for the state’s justice system. We need judges like Judge Paul Bugenhagen who have a clear understanding of the rule of law and will strive to uphold it every day on the bench,” said Justice Rebecca Bradley. Judge Paul Bugenhagen Jr was elected Waukesha County Circuit Court Judge in 2015 after defeating a two-term incumbent. He currently presides over the criminal division of the court. He spent the four previous years in the family and probate divisions of the court and was named head of the family court division in 2018. Paul resides in Mukwonago with his wife, Crosby, and their daughter. He faces Judge Lisa Neubauer on April 7, 2020. ### The District II Appellate Court includes Calumet, Fond du Lac, Green Lake, Kenosha, Manitowoc, Ozaukee, Racine, Sheboygan, Walworth, Washington, Waukesha, and Winnebago counties. This seat is currently held by Judge Lisa Neubauer. -

Please Visit Our Website At

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page County Government Telephone Directory .................. 2-3 County Government Addresses .................................. 3-4 Federal and State Officials ......................................... 5-7 Elective County Officers/Dept Heads ............................ 8 County Board Supervisor .......................................... 9-12 County Board Committees ...................................... 12-14 Town Officials……………………………………………… …..15-21 Village Officials………………………………………………. 21-28 City Official ............................................................. 29-31 County Email Addresses ......................................... 32-34 Iowa County Department Information .................... 34-36 Census of Iowa County IOWA COUNTY Total Precincts…………………………………..29 Townships…………………………………………14 Village………………………………………………13 Cities………………………………………………....2 Land Area………………………761 square miles 2010 Population…………………………..23,687 Please visit our website at: www.iowacounty.org 1 TELEPHONE DIRECTORY Area code (608) Aging & Disability Resource Ctr .......... 930-9835 ...................................... Fax: 935-0355 Airport ................................................... 987-9931 Bloomfield Healthcare & Rehabilitation 935-3321 ...................................... Fax: 937-0553 Child Support ........................................ 935-0390 ...................................... Fax: 935-0382 Clerk of Circuit Court ........................... 935-0395 ...................................... Fax: 935-0386 Coroner ................................................ -

State of the Judiciary Address 2020

STATE OF THE JUDICIARY ADDRESS 2020 THE COURAGE OF WISCONSIN COURTS Chief Justice Patience Drake Roggensack Wisconsin Supreme Court P.O. Box 1688 Madison, WI 53701 (608) 266-1888 Annual Meeting of the Wisconsin Judicial Conference November 5, 2020 ZOOM, Wisconsin The Courage of Wisconsin Courts 2020 Judicial Conference AMERICAN FLAG IN SUPREME COURT HEARING ROOM Pledge of Allegiance Marshal Tammy Johnson, Wisconsin Supreme Court Welcome to the 2020 Judicial Conference to you all. During this conference, we will have a conversation about the courage of Wisconsin courts — the judges who preside in them and their staffs. They have met and overcome the challenges presented by COVID-19, and have enabled Wisconsin courts to serve the people in spite of the pandemic. It has been said that courage is not the absence of fear, but the willingness to be present and respond in spite of fear. My favorite definition of courage is simply, “grace under fire.” Our courts have shown courage, again and again, whatever definition you choose. We also will explore together core legal issues such as Fourth Amendment expectations and First Amendment challenges as well as technology's effects on Wisconsin courts. We will discuss issues relating to personal security of judges and court personnel. The world is changing rapidly, and that is reflected in the types of issues we meet in our courts. There are times when the problems generated through senseless violence and drug abuse cause us to be at a loss to understand how best to respond to those problems in a legally and socially sufficient way. -

January Case Law Update Wisconsin Supreme Court Opinions

For more questions or comments about these cases, please contact: Brian W. Ohm, JD Dept. of Planning and Landscape Architecture, UW-Madison/Extension 925 Bascom Mall Madison, WI 53706 [email protected] January Case Law Update January 31, 2018 A summary of Wisconsin court opinions decided during the month of January related to planning For previous Case Law Updates, please go to: www.wisconsinplanners.org/learn/law-and-legislation Wisconsin Supreme Court Opinions Assessment Using Mass Appraisal Technique Was Appropriate Metropolitan Associates v. City of Milwaukee, 2018 WI 4, involved an excessive assessment action against the City of Milwaukee related to property taxes for seven properties owned by Metropolitan. Apartment properties owned by Metropolitan were initially assessed by the City using a “mass appraisal” technique, a process whereby an assessor values entire groups of property using systematic techniques and allowing for statistical testing. The City also conducted a more individual analysis of the property using a comparative sales approach that arrived at a value higher than that produced with the initial mass appraisal. Metropolitan challenged the City’s assessment of the properties based on the mass appraisal technique. An appraiser for Metropolitan concluded the properties had a lower value than reflected in the City’s assessment. Following a trial, the circuit court determined that the City’s assessment was more reliable and upheld the City’s assessment. The Wisconsin Court of Appeals upheld the Circuit Court’s decision. The Wisconsin Supreme Court, in a decision written by Justice Ann Walsh Bradley, affirmed the decision of the Court of Appeals. According to the Court majority, the City's assessment of the Apartments complied with Wis. -

Big Money Bulletin

Big Money Bulletin Come to Our Party! Inside Dear Friend, Page 2 Mark your calendar: Our annual meeting at the Influence Peddler Who Bought Our Supreme Lussier Family Heritage Center in rural Madison is set for Court? Thursday, May 12, from 5:30 to 8:00 p.m. 11 More Towns Say No to Citizens United We’ve got a great lineup for you. Our keynote Page 3 speaker is the media scholar and social critic Robert Behind That Zombie Homes Bill McChesney, co-author with Field Day for Landlords Who Wants Local Control? John Nichols most recently Page 4 of People Get Ready: The Annual Meeting Fight Against a Jobless No April Fool’s Joke Economy and a Citizenless Democracy. We also are honored to have Representative JoCasta Zamarripa, a Democrat, on the docket, along with Senator Rob Cowles, a Republican. One of our great partners, Andrea Kaminski, the head of the League of Women Voters of Wisconsin, will say a few words. And April 2016 Wisconsin poet Angie Trudell Vasquez, who works for the Edition No. 99 ACLU of Wisconsin, will share some of her art with us. It’s going to be a fun, fast-paced event, and you’ll receive wisdom and inspiration from our speakers. On the Web: www.wisdc.org I know I’m looking forward to it. And I’m looking forward to seeing you there. Please let us know if you will be attending by contacting Beverly at [email protected], or by calling us at (608) 255-4260. Best wishes, Influence Peddler of the Month Wisconsin Alliance for Reform, a conservative Madison-based group formed late last year that In March, our highly coveted award for the doled out an estimated $2.6 million on four television “Influence Peddler of the Month” went to ads and a radio ad to support Bradley.