Analysis of Structural Changes on Grape Grower's Return Per Ton a Case Study of Developing American Viticultural Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September Newsletter 2020

September 2020 Vol. IV, No. 3 An Exclusive Newsletter for The Vintners Club Members Lodi Vintners Notes What’s Inside From the Winemaker You Should Have Been There! Member Spotlight Featured Wines Recipe from Our Staff The Rippey Reserve Room The Vintners Club Exclusives Upcoming Events Current Wines From the Winemaker Covid-19 has changed our lives, including the wine industry. For those of you who have experienced symptoms or know someone who has, the virus is all too real. Our Tasting Room is open for tastings on the deck or around the fountain. Our team has worked hard to ensure your safety and enjoyment. August provided us with record setting hot days! This year, like last year, has been a less challenging growing season. Once again, we have a traditional start to the harvest with our first grapes arriving mid- August. This year’s harvest is yielding smaller, more flavorful grapes with juice that is deep in color and a promise of great wines. Not all grape varietals are picked at the same time. Grapes for sparkling wines are the first to be picked, usually in early August, marking the start of "crush." Next, most of the white grapes make their way from the vineyard to the crush pad. Harvest continues through late October – sometimes early November – for red varietals, as they take a bit longer to reach full maturation. Harvesting of Cabernet Sauvignon grapes begins later than most other varietals and typically lasts the longest. This year the Zinfandel vines at Lodi Vintners are heavy with fruit that is naturally flavorful. -

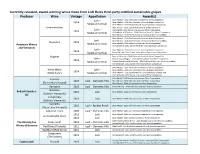

Currently-Released, Award-Winning Wines Made from Lodi Rules Third

Currently-released, award-winning wines made from Lodi Rules third-party certified sustainable grapes Producer Wine Vintage Appellation Award(s) Lodi – Silver Medal - 2016 International Women’s Wine Competition 2014 Silver Medal - 2016 San Francisco Chronicle Wine Competition Mokelumne River Silver Medal - 2016 Seattle Wine & Food Experience Competition Grenache blanc Best in Class - 2016 Sunset International Wine Competition Lodi – 2015 Gold Medal - 2016 Sunset International Wine Competition Mokelumne River Gold Medal & 95 Points - 2016 California State Fair Wine Competition Silver Medal - 2016 San Francisco International Wine Competition Silver Medal - 2016 San Francisco Chronicle Wine Competition Lodi – Rousanne 2014 Silver Medal - 2016 San Francisco International Wine Competition Acquiesce Winery Mokelumne River Silver Medal – 2016 California State Fair Wine Competition Bronze Medal - 2016 Seattle Wine & Food Experience Competition and Vineyards Lodi – 2014 Silver Medal - 2016 San Francisco Chronicle Wine Competition Mokelumne River Bronze Medal - 2016 Seattle Wine & Food Experience Competition Viognier Best of California - 2016 California State Fair Wine Competition Lodi – 2015 Best of Class of Region - 2016 California State Fair Wine Competition Mokelumne River Double Gold Medal & 98 Points - 2016 California State Fair Wine Competition Bronze Medal - 2016 Sunset International Wine Competition Silver Medal - 2016 International Women’s Wine Competition White Blend Lodi – 2014 Silver Medal - 2016 San Francisco Chronicle Wine Competition -

Lodi Wines Press Kit 2015

LoCA: The Wines of Lodi, California Press Kit 2015 LODI WINE COUNTRY Lodi—the Place: “Lodi Wine Country” is one of California’s major winegrowing regions, located 100 miles east of San Francisco near the San Joaquin/Sacramento River Delta, south of Sacramento and west of the Sierra Nevada mountain range. It is named after the most populous city within the region. Lodi is characterized by a rural atmosphere where wineries and farms run by 4th - and 5th generation families operate in tandem with a new group of vintners who have brought creative winemaking and cutting-edge technology to the region. In Lodi, grape-growing is inextricably woven into the culture: the city of Lodi’s police department prominently features a grape cluster in its logo, and high school teams are named after grape varieties. A Track Record of Continuous Success: Lodi has been a major winegrape growing region for over 150 years. Unlike many U.S. wine regions, Lodi actually prospered during Prohibition and as such has been a continuous source of wine grapes since the 1850s. In fact, when early trappers wandered into what is now Lodi, they called one stream they discovered "Wine Creek" because of the proliferation of wild vines found there. As more and more Italian and German immigrants made their homes in Lodi, vinifera varieties such as Zinfandel, Tokay, and Alicante appeared by the 1880s. Key Milestones In Lodi’s History: o Fruit supply routes to the East Coast had been well established and so home winemakers took advantage of the provisions of the Volstead Act during Prohibition by purchasing wine grapes from Lodi to make their legal allotment of wine. -

Wine Bottle Menu

W I N E S B Y T H E B O T T L E Because our inventory of the small-production wines we support is limited, we may run out occasionally. In addition, wines at Vino & Vinyl can be purchased to-go at a discounted rate of 25% (wine club = 35%). (If you’re on a mobile device, turning it sideways will make the reading more enjoyable!) A quick-ish note about this tiny bottle list: it has been tempting for us to go down the “Alice in Wonderland” spiral of trying to have a wine from every country in the world, let alone from specific regions. Instead, we started honing and focusing on what we really love and who we want to support. We want the majority of the money we purchase wine with, to go to wineries here on our soil, with the focus on the West Coast (but Texas is trying to get serious, too). Don’t worry if we don’t have what you’re looking for, because I promise… there are some amazing wines below. I even took the time to find or write a little blurb for each wine (who does that?), so that you can make a more educated “blind” purchasing decision. These are the kinds of wines we love drinking at our house: great Cabernet, awesome Blends, life-changing Pinot Noir, all-day-rose (bro-zay, as I like to call it), and Champagne (which needs no introduction). Thank you so much for joining us. I hope you love it here. -

Rick's Red Wine Reviews & Recommendations

Rick’s Grape Skinny [email protected] May 2015 “Wine is sunlight…held together by water!” (Galileo Galilei) The Low Down on Lodi! only been over the last ten years or so that Lodi What’s that you say? What’s a Lodi?! No…it’s sourced wines have exploded in popularity and not a Star Wars character! That would be begun occupying lots of space on the shelves of Lowbacca…Wookie’s and Chewbacca’s wine shops coast to coast. While Lodi has been nephew…but don’t feel too badly…as you’re not known and recognized mostly for its vibrant and the only one who might not know the low down über-lush Old Vine Zinfandel wines, more than on Lodi! First, Lodi – pronounced lo ´ - dye by 45 grape varietals are actually grown there. the way -- is not a what! Lodi is a place…both a city and an American Viticultural Area (AVA) that is situated in California’s huge Central Valley. By way of context, Napa and Sonoma are also AVAs…and though you might never have heard of Lodi or know where Lodi is, know this – Lodi winegrowers and winemakers are making some of the best and most amazing wines coming out of California these days!! Honest! For all intents and purposes, the Lodi AVA is located about 60 miles east of San Francisco In 2006, the Feds approved the designation of seven viticultural Appellations within Lodi – Alta Mesa, Borden Ranch, Clements Hills, Cosumnes River, Jahant, Mokelumne River, and Sloughhouse. And while these specific growing regions aren’t yet rolling off the tongues of aficionados who are quick to mention the likes of Carneros, Chalk Hill, Dry Creek, Howell and Spring Mountain Districts, etc…that will certainly happen over time. -

Wines Fit for a King Kit 2

Palladio Chianti DOCG Don’t be quick to pass on what appears as just another simple Chianti from Tuscany. Palladio is an homage to one of the world’s most iconic and influential architects from the High Renaissance, Andrea Palladio. Like Palladio, Alberto Antonini has made a name for himself as a Master Winemaker, reviving traditional wineries with a modern approach that maintains the well-loved chianti profile. The price plays down the serious nature of the wine, a classic style with its bright cherry, dried herbs, Wines Fit for a King and earthy notes. Armida Lodi Zinfandel 6/16/2020 Robert Frugoli grew up drinking his grandfather’s homemade wine and was determined to make his own. In 1979, he got his chance and purchased an already existing vineyard. He named it Armida after his beloved Italian grandmother. The Foley Family has carried on the winery legacy in producing Zinfandels from old vines — 60 to 100 years old — that are serious like the Palladio Chianti, but still priced accessibly. Three Rivers Cabernet Sauvignon Three Rivers is aptly named for the the most important Armida Lodi rivers in eastern Washington: the Columbia, Snake, and Three Rivers Zinfandel Walla Walla. Washington Cabernet Sauvignons are Palladio Cabernet Chianti DOCG consistently smooth and exude black fruits’ riper qualities. Sauvignon for customers of COTTAGE GROVE| RAMSEY| OSSEO | ANDOVER | ROSEVILLE | CHANHASSEN | ST. LOUIS PARK | BLAINE | WOODBURY Place Matters Chianti, Italy Chianti is the oldest and most recognized wine region in Tuscany. The Apennine Mountains’ spine runs through the Tuscan region, creating hillsides for Sangiovese grapes to thrive. -

The International Wine Review

Complimentary Copy The International Wine Review California Zinfandel: A New Look Foreword by Joel Peterson Special Double Issue May/June 2017 1 Foreward Zinfandel has a long history in California. Much of that history is about adaptation to changing circumstance. The last 40 years have brought more change to the style and quality of the wines made from Zinfandel than ever before. Hence, while much has been written about this grape and its wine over the years, it is a bit surprising that a comprehensive up-to-date synopsis of its history in California, the growing regions that it inhabits, the winemakers who have wholeheartedly embraced it, or the excellent wines that are crafted from Zinfandel has not emerged. Fortunately that has changed with this report. As the modern California wine business has emerged from the late 1960’s the skill of its winemakers, the understanding of viticulture, wine making technology and consumer enthusiasm have all reach levels never before achieved. This has benefited Zinfandel greatly. Its ancient DNA has found a comfortable fit in the evolving California wine scene. The wines are better, at all levels, than they have ever been. The current review of California Zinfandel from the good people at the International Wine Review could not come at a more opportune time. They have written a thorough review of the current state of Zinfandel in California, its history, growing regions, winemakers, wineries and of course, its wine. While I cannot endorse the scores given the wines, as they are entirely the opinion of the International Wine Review. -

CHARDONNAY Lodi

CLARKSBURG CLARSBUR LDI LDI SAN FRANCISC NTERE AS RBLES LS ANELES SAN FRANCISC CERTIFIED SUSTAINABLE CHARDONNAY MONTEREY Lodi AVA PASO ROBLES varietal: 90% Chardonnay, 5% Viognier and 5% Sauvignon Blanc region: Lodi AVA LS ANELES vineyard: The Tortoise Creek Chardonnay is sourced from certified sustainably farmed vineyards in the sandy loams and alluvial clay soils of Lodi. The vineyards take advantage of the cool climate gap between the northern and southern coastal ranges surrounding the San Francisco Bay. As the day’s temperature rises, cool breezes drift in from the Delta, keeping the nights cool which is ideal for devel- oping complex long finishing wines. The climate in Lodi is almost identical to Napa with the same mean annual temperatures. winemaking: Grapes are picked at night when it is coolest. Whole cluster pressing preserves the natural acid balance present at harvest and also minimizes harsh tannins. The pressed juice is clarified and then undergoes a cool, slow fermentation in stainless steel vats which preserves the fresh varietal character of the Chardon- nay grape. After fermentation, the wine is stirred on its lees to extract richness and depth and aromas. The wine does NOT go through malolactic fermentation but a percentage does spend a few months in French oak. Both the Viognier and Sauvignon Blanc add a wonderful complexity to the wine. tasting: Tortoise Creek Chardonnay is extremely elegant and fresh with lovely aromas of pears, apples and white flowers. Its creamy texture is supported by fresh acidity and a long, clean finish. UPC# 0 89832 41205 2 12pk / 750ml food pairing: Ideal with all seafood, chicken and cream based pastas. -

2021 Double Gold Medal Winners

2021 Double Gold Medal Winners OC Fair Commercial Wine Competition Co-sponsored by the Orange County Wine Society Sycamore Ranch Vineyard & Winery 99 Points 2019 Mourvedre California Galleano Winery Inc 98 Points NV Mission Old Vine Cucamonga Valley AVA Husch Vineyards 97 Points 2017 Gewürztraminer Dry, Late Harvest Anderson Valley AVA Macchia Winery 97 Points 2019 Zinfandel old vine Lodi AVA Marin's Vineyard 97 Points 2020 Viognier Monterey County Schug Carneros Estate Winery 97 Points 2020 Sauvignon Blanc Sonoma Coast AVA Acquiesce Winery 96 Points 2020 Viognier Mokelumne River AVA Bellante Family Winery 96 Points 2018 Mourvedre 2018 Mourvedre, 95% Mourvedre, 5% Syrah Los Olivos District AVA, Camp Four Vineyard Cass Winery 96 Points 2020 Roussanne 100% Roussanne Paso Robles Geneseo District AVA Copyright Orange County Wine Society - Confidential and Proprietary Lewis Grace Winery 96 Points 2018 Syrah Sierra Foothills AVA, Renner Vineyard Napa de Oro 96 Points 2018 Chardonnay Non ML+ 100% Barrel Fermented Carneros AVA, Truchard Vineyards Pennyroyal Farm 96 Points 2018 Pinot Noir Anderson Valley AVA Rancho de Philo Winery 96 Points NV Sherry Mission, Triple Cream Sherry Cucamonga Valley AVA Robert Hall Winery 96 Points 2018 Syrah 92% Syrah, 8% Grenache Blanc, Cavern Select Paso Robles AVA Sobon Wine Company, LLC 96 Points 2020 Viognier Amador County Sycamore Ranch Vineyard & Winery 96 Points 2019 GSM 34% Grenache, 33% Syrah, 33% Mourvedre California Alta Colina Vineyard & Winery 95 Points 2018 Syrah Alta Colina Vineyard, 97% Syrah, 2% -

Loca: the Wines of Lodi, California Press Kit 2016

LoCA: The Wines of Lodi, California Press Kit 2016 1 LODI WINE COUNTRY Ø Lodi—the Place: “Lodi Wine Country” is one of California’s major winegrowing regions, located 100 miles east of San Francisco near the San Joaquin/Sacramento River Delta, south of Sacramento and west of the Sierra Nevada mountain range. It is named after the most populous city within the region. Lodi is characterized by a rural atmosphere where wineries and farms run by 4th - and 5th generation families operate in tandem with a new group of vintners who have brought creative winemaking and cutting-edge technology to the region. In Lodi, grape-growing is inextricably woven into the culture: the city of Lodi’s police department prominently features a grape cluster in its logo, and high school teams are named after grape varieties. Ø A Track Record of Continuous Success: Lodi has been a major winegrape growing region for over 150 years. Unlike many U.S. wine regions, Lodi actually prospered during Prohibition and as such has been a continuous source of wine grapes since the 1850s. In fact, when early trappers wandered into what is now Lodi, they called one stream they discovered "Wine Creek" because of the proliferation of wild vines found there. As more and more Italian and German immigrants made their homes in Lodi, vinifera varieties such as Zinfandel, Tokay, and Alicante appeared by the 1880s. Ø Key Milestones In Lodi’s History: o Fruit supply routes to the East Coast had been well established and so home winemakers took advantage of the provisions of the Volstead Act during Prohibition by purchasing wine grapes from Lodi to make their legal allotment of wine. -

2019 the Toast of the Coast Results by Award

2019 The Toast of the Coast Results by Award Director’s Awards score Brand Vintage WineType Appellation Price The Toast of the Coast 96 Francis Ford Coppola Director's Cut 2016 Technicolor Dry Creek Valley $40.00 Best of Dry Creek Valley AVA 96 Francis Ford Coppola Director's Cut 2016 Technicolor Dry Creek Valley $40.00 Best Red Blend 96 Francis Ford Coppola Director's Cut 2016 Technicolor Dry Creek Valley $40.00 Best Cabernet Sauvignon 95 Heritance Winery 2015 Cabernet Sauvignon Napa Valley $28.00 Best Charbono 95 Jeff Runquist 2016 Charbono Sierra Foothills $28.00 Best Merlot 95 Christopher Cameron Vineyards 2016 Reserve Merlot, Van Alyea Ranch Dry Creek Valley $60.00 Best of Amador County 95 Jeff Runquist 2016 Tempranillo, Shake Ridge Ranch Amador County $32.00 Best of Italy 95 Antinori 2015 Marchese, Riserva Chianti Classico DOCG $39.99 Best of Lodi AVA 95 Oak Farm Vineyards 2018 Sauvignon Blanc Lodi $19.00 Best of Monterey County 95 Sofia 2018 Rosé Monterey County $19.00 Best of Napa Valley AVA 95 Heritance Winery 2015 Cabernet Sauvignon Napa Valley $28.00 Best of Paso Robles AVA 95 Héroe 2016 Viongier Paso Robles $25.00 Best of Sierra Foothills AVA 95 Jeff Runquist 2016 Charbono Sierra Foothills $28.00 Best of Sonoma Coast AVA 95 Rodney Strong Vineyards 2014 Pinot Noir, Estate Vineyards Sonoma Coast $30.00 Best Petit Verdot 95 Shale Oak Winery 2014 Petit Verdot Paso Robles $40.00 Best Petite Sirah 95 Parvaneh 2015 Petite Sirah Paso Robles $29.00 Best Pinot Noir 95 Rodney Strong Vineyards 2014 Pinot Noir, Estate Vineyards Sonoma -

Gold Silk Oak Vineyards December 2015 2013 Chardonnay Download

vol. 25 no. 12 GOLD SERIES w WINE PRESS Medal Winning Wines from California’s Best Family-Owned Wineries. Chesterfield Cellars & Silk Oak Vineyards Lodi GOLD MEDAL WINE CLUB America’s Leading Independent Wine Club Since 1992 chesterfield cellars 2011 cabernet sauvignon lodi 1,080 Cases Produced The Chesterfield Cellars 2011 Cabernet Sauvignon comes from the Lone Dove Vineyard, nestled at the base of the Sierra Foothills in Lodi wine country. This twenty-five acre property yields consistent, high quality fruit, making it a desirable vineyard in the region. Black ruby in color, the 2011 Lone Dove Vineyard Cabernet Sauvignon offers bright, spicy aromas of cassis, chutney, dried cherries, spicy cornichon and chocolate nuts. The palate is soft and full bodied with flavors of dark currant, cranberry, sweet marinated beets, and anise. Beverage Testing Institute calls this “a delicious and satisfying Cabernet with nice layers of spice and fruit flavors.” Aged 22 months in French Oak. Enjoy now until 2021. 93 POINTS + GOLD MEDAL - Beverage Testing Institute’s World Wine Championships silk oak vineyards 2013 chardonnay lodi 1,463 Cases Produced The fruit for Silk Oak Vineyards’ 2013 Chardonnay was hand selected from a handful of top Lodi vineyards, promoting a range of flavor complexities that find excellent balance in this wine. Overall, this Chardonnay is rich and concentrated with the perfect blend of fruit and light oak. Intense notes of pear and grapefruit come through on the silky palate, while subtle nuances of orange, toasty vanilla, and honey linger on the finish with a touch of cinnamon spice. Aged in oak.