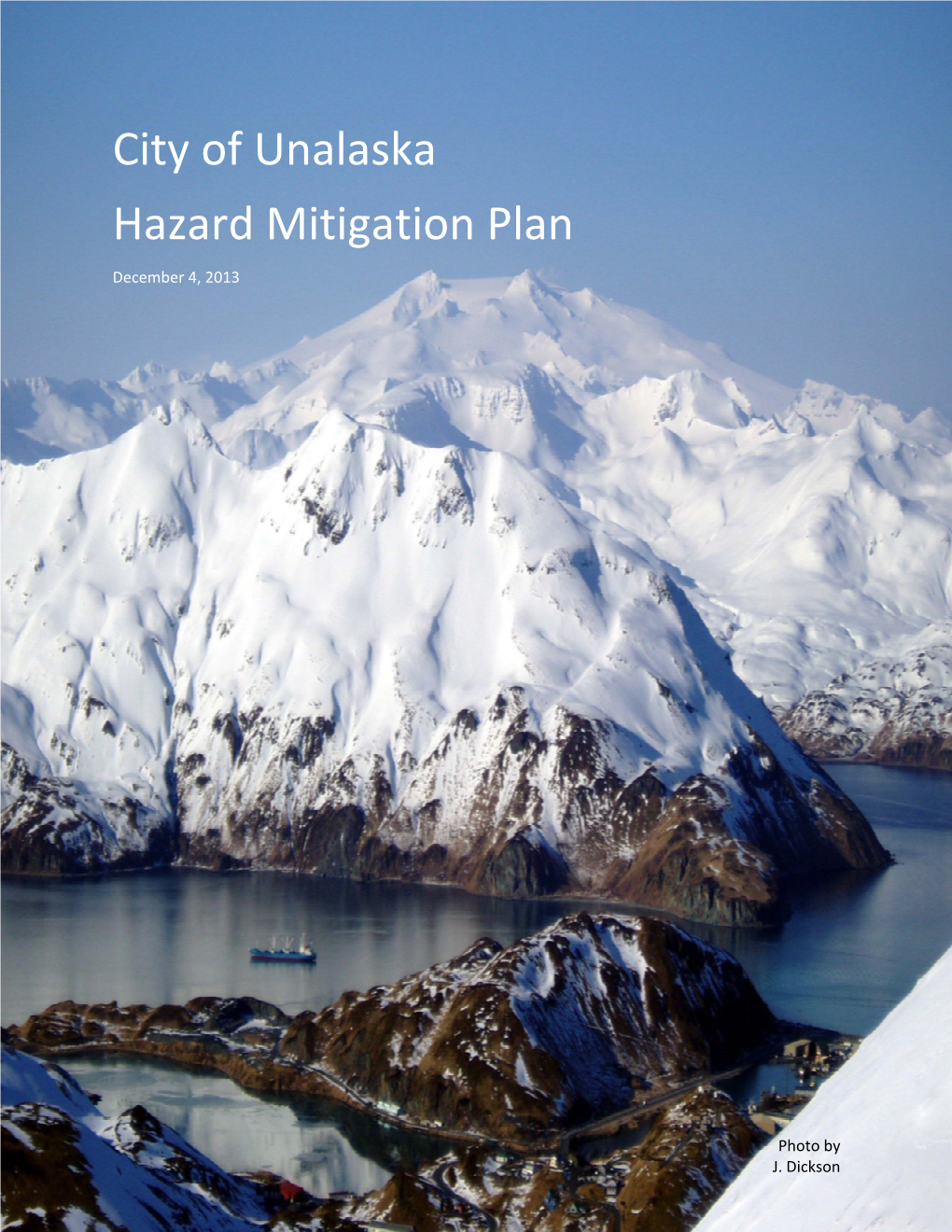

City of Unalaska Hazard Mitigation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalog of Earthquake Hypocenters at Alaskan Volcanoes: January 1 Through December 31, 2009

Catalog of Earthquake Hypocenters at Alaskan Volcanoes: January 1 through December 31, 2009 Data Series 531 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Catalog of Earthquake Hypocenters at Alaskan Volcanoes: January 1 through December 31, 2009 By James P. Dixon, U.S. Geological Survey, Scott D. Stihler, University of Alaska Fairbanks, John A. Power, U.S. Geological Survey, and Cheryl K. Searcy, U.S. Geological Survey Data Series 531 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2010 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1-888-ASK-USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Dixon, J.P., Stihler, S.D., Power, J.A., and Searcy, Cheryl, 2010, Catalog of earthquake hypocenters at Alaskan volcanoes: January 1 through December 31, 2009: U.S. Geological -

Redalyc.ACTIVIDAD ERUPTIVA Y CAMBIOS GLACIARES EN EL

Boletín de Geología ISSN: 0120-0283 [email protected] Universidad Industrial de Santander Colombia Julio-Miranda, P.; Delgado-Granados, H.; Huggel, C.; Kääb, A. ACTIVIDAD ERUPTIVA Y CAMBIOS GLACIARES EN EL VOLCÁN POPOCATÉPETL, MÉXICO Boletín de Geología, vol. 29, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2007, pp. 153-163 Universidad Industrial de Santander Bucaramanga, Colombia Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=349632018015 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto ACTIVIDAD ERUPTIVA Y CAMBIOS GLACIARES EN EL VOLCÁN POPOCATÉPETL, MÉXICO Julio-Miranda, P. 1; Delgado-Granados, H. 2; Huggel, C.3 y Kääb, A. 4 RESUMEN El presente trabajo, se centra en el estudio del impacto de la actividad eruptiva del volcán Popocatépetl en el área glaciar durante el período 1994-2001. Para determinar el efecto de la actividad eruptiva en el régimen glaciar, se realizaron balances de masa empleando técnicas fotogramétricas, mediante la generación de modelos digitales de elevación (MDE). La compa- ración de MDEs permitió establecer los cambios glaciares en términos de área y volumen tanto temporales como espaciales. Así mismo, los cambios morfológicos del área glaciar fueron determinados con base en la fotointerpretación, de manera que los datos obtenidos por este procedimiento y los obtenidos mediante la comparación de los MDE se relacionaron con la actividad eruptiva a lo largo del periodo de estudio, estableciendo así la relación entre los fenómenos volcánicos y los cambios glaciares. -

Chronology and References of Volcanic Eruptions and Selected Unrest in the United States, 1980- 2008

Chronology and References of Volcanic Eruptions and Selected Unrest in the United States, 1980- 2008 By Angela K. Diefenbach, Marianne Guffanti, and John W. Ewert Open-File Report 2009–1118 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2009 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Suggested citation Diefenbach, A.K., Guffanti, M., and Ewert, J.W., 2009, Chronology and references of volcanic eruptions and selected unrest in the United States, 1980-2008: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2009-1118, 85 p. [http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2009/1118/]. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. 2 Contents Part I…..............................................................................................................................................4 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................4 -

Unalaska Hazard Mitigation Plan 2018

Unalaska, Alaska Multi-Jurisdictional Hazard Mitigation Plan Update April 2018 Prepared for: City of Unalaska and Qawalangin Tribe of Unalaska City of Unalaska Hazard Mitigation Plan THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK INTENTIONALLY ii City of Unalaska Hazard Mitigation Plan Table of Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Hazard Mitigation Planning ..................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Grant Programs with Mitigation Plan Requirements ............................... 1-1 1.2.1 HMA Unified Programs ............................................................... 1-2 2. Community Description ....................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 Location, Geography, and History ........................................................... 2-1 2.2 Demographics .......................................................................................... 2-3 2.3 Economy .................................................................................................. 2-4 3. Planning Process .................................................................................................. 3-1 3.1 Planning Process Overview ..................................................................... 3-1 3.2 Hazard Mitigation Planning Team ........................................................... 3-3 3.3 Public Involvement & Opportunities for Interested Parties to participate ................................................................................................ -

Geology of the Prince William Sound and Kenai Peninsula Region, Alaska

Geology of the Prince William Sound and Kenai Peninsula Region, Alaska Including the Kenai, Seldovia, Seward, Blying Sound, Cordova, and Middleton Island 1:250,000-scale quadrangles By Frederic H. Wilson and Chad P. Hults Pamphlet to accompany Scientific Investigations Map 3110 View looking east down Harriman Fiord at Serpentine Glacier and Mount Gilbert. (photograph by M.L. Miller) 2012 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Contents Abstract ..........................................................................................................................................................1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................1 Geographic, Physiographic, and Geologic Framework ..........................................................................1 Description of Map Units .............................................................................................................................3 Unconsolidated deposits ....................................................................................................................3 Surficial deposits ........................................................................................................................3 Rock Units West of the Border Ranges Fault System ....................................................................5 Bedded rocks ...............................................................................................................................5 -

USGS Open-File Report 2004-1234

Catalog of Earthquake Hypocenters at Alaskan Volcanoes: January 1 through December 31, 2003 By James P. Dixon1, Scott D. Stihler2, John A. Power3, Guy Tytgat2, Seth C. Moran4, John J. Sánchez2, Stephen R. McNutt2, Steve Estes2, and John Paskievitch3 Open-File Report 2004-1234 2004 Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey 1 Alaska Volcano Observatory, U. S. Geological Survey, 903 Koyukuk Drive, Fairbanks, AK 99775-7320 2 Alaska Volcano Observatory, Geophysical Institute, 903 Koyukuk Drive, Fairbanks, AK 99775-7320 3 Alaska Volcano Observatory, U. S. Geological Survey, 4200 University Drive, Anchorage, AK 99508-4667 4 Cascades Volcano Observatory, U. S. Geological Survey, 1300 SE Cardinal Ct., Bldg. 10, Vancouver, WA 99508 2 CONTENTS Introduction...................................................................................................3 Instrumentation .............................................................................................5 Data Acquisition and Reduction ...................................................................8 Velocity Models...........................................................................................10 Seismicity.....................................................................................................11 Summary......................................................................................................14 References....................................................................................................15 -

THE ALEUTIAN ISLANDS: THEIR PEOPLE and NATURAL HISTORY

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION WAR BACKGROUND STUDIES NUMBER TWENTY-ONE THE ALEUTIAN ISLANDS: THEIR PEOPLE and NATURAL HISTORY (With Keys for the Identification of the Birds and Plants) By HENRY B. COLLINS, JR. AUSTIN H. CLARK EGBERT H. WALKER (Publication 3775) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION FEBRUARY 5, 1945 BALTIMORE, MB., U„ 8. A. CONTENTS Page The Islands and Their People, by Henry B. Collins, Jr 1 Introduction 1 Description 3 Geology 6 Discovery and early history 7 Ethnic relationships of the Aleuts 17 The Aleutian land-bridge theory 19 Ethnology 20 Animal Life of the Aleutian Islands, by Austin H. Clark 31 General considerations 31 Birds 32 Mammals 48 Fishes 54 Sea invertebrates 58 Land invertebrates 60 Plants of the Aleutian Islands, by Egbert H. Walker 63 Introduction 63 Principal plant associations 64 Plants of special interest or usefulness 68 The marine algae or seaweeds 70 Bibliography 72 Appendix A. List of mammals 75 B. List of birds 77 C. Keys to the birds 81 D. Systematic list of plants 96 E. Keys to the more common plants 110 ILLUSTRATIONS PLATES Page 1. Kiska Volcano 1 2. Upper, Aerial view of Unimak Island 4 Lower, Aerial view of Akun Head, Akun Island, Krenitzin group 4 3. Upper, U. S. Navy submarine docking at Dutch Harbor 4 Lower, Village of Unalaska 4 4. Upper, Aerial view of Cathedral Rocks, Unalaska Island 4 Lower, Naval air transport plane photographed against peaks of the Islands of Four Mountains 4 5. Upper, Mountain peaks of Kagamil and Uliaga Islands, Four Mountains group 4 Lower, Mount Cleveland, Chuginadak Island, Four Mountains group .. -

PROPERN of Fairbanks, AK 99709 DGGS LIBRARY Open File Repod 98-582 Icpbs

EUSGS science tor a changing- - world DEPARTMENT OF THE iMTEIWlOR U.S. GEBLOGIICAL SURVEY I I CATALOG OF THE HISTORICALLY ACTIVE VOLCANOES OF ALASKA T.P. Miller I, R.G. McGirnsey l, D.W.Richter I, J.R. Riehle $ CC.J.Nye 2, M.E. \daunt l, and J.A. Durnoufin lU.S, Wlogieal Suwey Anehwage, AK 99508 2AlaskoDivisWl of Gedoglcaland Geophysicol Surveys PROPERN OF Fairbanks, AK 99709 DGGS LIBRARY Open File Repod 98-582 IcPBS Done in cooperation with the lnternaticnai Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth's Interior (IAVCEI) and the Catalog of Active Volcanoes of the W~rld(CAVW) Project This repart is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards (or with the North American Stsatigraphlc Code). Any use of trade. product or firm names is for I I descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Wew 10 t/7c west across the s~lrnrnircaldera of Mr. U+angell. The Eusf Crarer (foreground),North Crater (steaming)atld Ukst Crater (le~?)arc on the rim of rhe 4x6 krn cllldem. Mr. Dnrm is in the right background. Phoro by R.J. Motyka. Introduction ..........................................................................................................................................................................i Previous work .......................................................................................................................................................................ii Methodology ........................................................................................................................................................................ -

Volcanology: Electric Eruption

news & views VOLCANOLOGY Electric eruption On the morning of 24 August, ad 79, Mount Vesuvius in the Bay of Naples, Italy, exploded into activity. The eruption caught the roman occupants of Pompeii and Herculaneum utterly unawares. The cities were rapidly buried by thick ash fall and pyroclastic surges, killing thousands of people. In a letter to the historian Tacitus, Pliny the Younger, an eyewitness and survivor of the eruption, described “frightening dark clouds, rent by lightning twisted and hurled” (http://go.nature.com/gkcLgn). Volcanic lightning has since been documented during many historical eruptions. More recently, spectacular lightning was observed during the eruptions of Mount Redoubt in Alaska, USA, in 2009 and Eyjafjallajökull Volcano in Iceland in 2010. The lightning generally occurs within the volcanic plume — a spreading column of ash, rock and hot gases blasted from the volcano vent. Although the details of the processes are poorly understood, volcanic lightning is thought to be triggered by the fragmentation of, and high-speed collisions between, volcanic rocks and ash as they exit the vent, as well as by the interactions between super-cooled water / ALAMY IMAGES © ARCTIC droplets and ice particles in higher, cooler parts of the column. The collisions create positive and negative electrically charged analysed ash deposits collected from The glass spherules mostly formed regions within the volcanic plume that are the Mount Redoubt and Eyjafjallajökull from melting of the smallest individual ash equalized by an electrical discharge that eruptions and found tiny glass spherules grains or from the fusion of several melted creates a lightning flash. (less than 100 μm across), which could ash grains. -

Historically Active Volcanoes of Alaska Reference Deck Activity Icons a Note on Assigning Volcanoes to Cards References

HISTORICALLY ACTIVE VOLCANOES OF ALASKA REFERENCE DECK Cameron, C.E., Hendricks, K.A., and Nye, C.J. IC 59 v.2 is an unusual publication; it is in the format of playing cards! Each full-color card provides the location and photo of a historically active volcano and up to four icons describing its historical activity. The icons represent characteristics of the volcano, such as a documented eruption, fumaroles, deformation, or earthquake swarms; a legend card is provided. The IC 59 playing card deck was originally released in 2009 when AVO staff noticed the amusing coincidence of exactly 52 historically active volcanoes in Alaska. Since 2009, we’ve observed previously undocumented persistent, hot fumaroles at Tana and Herbert volcanoes. Luckily, with a little help from the jokers, we can still fit all of the historically active volcanoes in Alaska on a single card deck. We hope our users have fun while learning about Alaska’s active volcanoes. To purchase: http://doi.org/10.14509/29738 The 54* volcanoes displayed on these playing cards meet at least one of the criteria since 1700 CE (Cameron and Schaefer, 2016). These are illustrated by the icons below. *Gilbert’s fumaroles have not been observed in recent years and Gilbert may be removed from future versions of this list. In 2014 and 2015, fieldwork at Tana and Herbert revealed the presence of high-temperature fumaroles (C. Neal and K. Nicolaysen, personal commu- nication, 2016). Although we do not have decades of observation at Tana or Herbert, they have been added to the historically active list. -

Preliminary Volcano-Hazard Assessment for Gareloi Volcano, Gareloi Island, Alaska

no O lca bs o er V v a a k t o s r a y l A U S S G G S G - AD UAF/GI - Preliminary Volcano-Hazard Assessment for Gareloi Volcano, Gareloi Island, Alaska Scientific Investigations Report 2008-5159 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey The Alaska Volcano Observatory (AVO) was established in 1988 to monitor dangerous volcanoes, issue eruption alerts, assess volcano hazards, and conduct volcano research in Alaska. The cooperating agencies of AVO are the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), the University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute (UAFGI) , and the Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys (ADGGS). AVO also plays a key role in notification and tracking eruptions on the Kamchatka Peninsula of the Russian Far East as part of a formal working relationship with the Kamchatkan Volcanic eruptions Response Team. Cover: Lava flows from a 20th-century eruption drape the south flank of Gareloi’s South Peak crater. The white zone on the crater headwall is an extensive fumarole field. Photograph by R.G. McGimsey, August 2003. Preliminary Volcano-Hazard Assessment for Gareloi Volcano, Gareloi Island, Alaska By Michelle L. Coombs, Robert G. McGimsey, and Brandon L. Browne Scientific Investigations Report 2008–5159 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2008 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS--the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. -

Foundation Document Overview – Lake Clark National Park

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Lake Clark National Park and Preserve Alaska Contact Information For more information about the Lake Clark National Park and Preserve Foundation Document, contact: [email protected] or (907) 644-3626 or write to: Superintendent, Lake Clark National Park and Preserve, 240 West 5th Avenue, Suite 236, Anchorage, AK 99501 Purpose Significance and Fundamental Resources and Values Significance statements express why Lake Clark National Park and Preserve resources and values are important enough to merit national park unit designation. Statements of significance describe why an area is important within a global, national, regional, and systemwide context. These statements are linked to the purpose of the park unit, and are supported by data, research, and consensus. Significance statements describe the distinctive nature of the park and inform management decisions, focusing efforts on preserving and protecting the most important resources and values of the park unit. Fundamental resources and values are those features, systems, processes, experiences, stories, scenes, sounds, smells, or other attributes determined to merit primary consideration during planning and management processes because they are essential to achieving the purpose of the park and maintaining its significance. The purpose of LAKE CLARK NATIONAL PARK AND PRESERVE is to protect a region of dynamic geologic and ecological processes that create scenic mountain landscapes, unaltered