Blood and Documentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Infrastructure of the Fur Trade in the American Southwest, 1821-1840

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Plan B and other Reports Graduate Studies 5-2014 The Infrastructure of the Fur Trade in the American Southwest, 1821-1840 Hadyn B. Call Utah State Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports Part of the American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Call, Hadyn B., "The Infrastructure of the Fur Trade in the American Southwest, 1821-1840" (2014). All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. 367. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports/367 This Creative Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Plan B and other Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INFRASTRUCTURE OF THE FUR TRADE IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEST, 1821-1840 by Hadyn B. Call A plan-B thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: _________________________ _________________________ John D. Barton David R. Lewis Major Professor Committee Member _________________________ Robert Parson Committee Member UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, UT 2014 2 THE INFRASTRUCTURE OF THE FUR TRADE IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEST, 1821-1840 Introduction Careful study of the published history of the American Southwest reveals that historians have not provided a comprehensive analysis of the infrastructure that enabled the fur trade in the American Southwest to thrive. Analysis of that infrastructure unveils an amalgamation of blended characteristics derived from the French, British, and American systems along with characteristics derived from the Southwest’s own evolutionary development over time and space. -

Kit Carson's Last Fight: the Adobe Walls Campaign of 1864 David A

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 4-12-2017 Kit Carson's Last Fight: The Adobe Walls Campaign of 1864 David A. Pafford University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Part of the Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Pafford, David A.. "Kit Carson's Last Fight: The Adobe Walls Campaign of 1864." (2017). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ hist_etds/165 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. David A. Pafford Candidate History Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Paul A. Hutton, Chairperson Dr. L. Durwood Ball Dr. Margaret Connell-Szasz Dr. Jerry D. Thompson i KIT CARSON’S LAST FIGHT: THE ADOBE WALLS CAMPAIGN OF 1864 by Name: DAVID A. PAFFORD B.S., History, Eastern Oregon State College, 1994 M.A., Christian Ministry, Abilene Christian University, 2006 M.A., History, University of New Mexico, 2010 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy History The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May 2017 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Writing a book, especially a first book, requires a LOT of assistance – so much so that any list of incurred debts while composing it must be incomplete. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Great

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Great American Desert: Arid Lands, Federal Exploration, and the Construction of a Continental United States DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History by Erik Lee Altenbernd Dissertation Committee: Professor David Igler, Chair Professor William Deverell Associate Professor Laura Mitchell © 2016 Erik Lee Altenbernd DEDICATION To Julie, Alex, Henry and Dolores For My father ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv CIRRICULUM VITAE v ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: First Desert: Exploration of the Great Plains after the 27 Louisiana Purchase CHAPTER 2: Second Desert: Exploration of the Transrockies 68 West during the Era of Manifest Destiny CHAPTER 3: Mapping the Desert: Appraising Topography and Climate 110 after the Transcontinental Railroad CHAPTER 4: Mapping the Desert Sublime: The Colorado Plateau and 152 the Geological Aesthetics of the Modern American Desert CONCLUSION 210 BIBLIOGRAPHY 217 APPENDIX: Figures 245 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to begin by thanking my advisor, David Igler. David’s unerring advice and unflagging support for a project as nebulous as “the desert” has been a stroke a great fortune. David’s caring and conscientious commitment to his students is second to none. I cannot thank him enough for his patience with short deadlines and half-baked prose. More than that, I also thank him and Cindy for providing me and my family with warm memories eating half-baked pies and finely smoked ribs under a gloaming Pasadena sky. Special thanks also go to Bill Deverell and Laura Mitchell. Bill, along with David, has served as a great mentor and inspiration. -

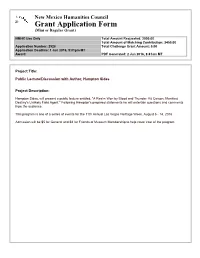

NMHC Grant Application #. 2528

New Mexico Humanities Council Grant Application Form (Mini or Regular Grant) NMHC Use Only Total Amount Requested: 2000.00 Total Amount of Matching Contribution: 3450.00 Application Number: 2528 Total Challenge Grant Amount: 0.00 Application Deadline: 1 Jun 2016, 5:01pm MT Award: PDF Generated: 2 Jun 2016, 8:41am MT Project Title: Public Lecture/Discussion with Author, Hampton Sides Project Description: Hampton Sides, will present a public lecture entitled, "A Realm Won by Blood and Thunder: Kit Carson, Manifest Destiny's Unlikely Field Agent." Following Hampton's prepared statements he will entertain questions and comments from the audience. This program is one of a series of events for the 11th Annual Las Vegas Heritage Week, August 6 - 14, 2016. Admission will be $5 for General and $3 for Friends of Museum Membership to help cover cost of the program Sponsoring Organization: Friends of the City of Las Vegas Museum and Rough Riders Memorial Collection Description: The Friends of the Museum was established in 1997 to support the Las Vegas City Museum with volunteers, funds and special public programs. It delivers Museum and Friends information to the public through a regular Newsletter and collaborates with other community organizations Mission: The mission of the Friends of the Museum is to enhance the Museum's obligation to the collection entrusted to it as patrimony by members of the community. It deliberates and generates ideas fro securing both human and financial resources for the care of the collection, for scholarly research, -

Blood and Thunder: an Epic of the American West (Paperback)

Blood and Thunder: An Epic of the American West (Paperback) < Kindle / WDKOEJV1YE Blood and Th under: A n Epic of th e A merican W est (Paperback) By Hampton Sides Random House USA Inc, United States, 2007. Paperback. Condition: New. Reprint. Language: English . Brand New Book. A magnificent history of the American conquest of the West; a story full of authority and color, truth and prophecy (The New York Times Book Review). In the summer of 1846, the Army of the West marched through Santa Fe, en route to invade and occupy the Western territories claimed by Mexico. Fueled by the new ideology of Manifest Destiny, this land grab would lead to a decades-long battle between the United States and the Navajos, the fiercely resistant rulers of a huge swath of mountainous desert wilderness. At the center of this sweeping tale is Kit Carson, the trapper, scout, and soldier whose adventures made him a legend. Sides shows us how this illiterate mountain man understood and respected the Western tribes better than any other American, yet willingly followed orders that would ultimately devastate the Navajo nation. Rich in detail and spanning more than three decades, this is an essential addition to our understanding of how the West was really won. READ ONLINE [ 6.44 MB ] Reviews I actually started reading this article publication. We have read and that i am confident that i am going to planning to study yet again once again later on. You can expect to like how the author compose this pdf. -- Zoe Hilpert Simply no phrases to spell out.