Imaging Guided Thoracic Interventions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trauma-Associated Pulmonary Laceration in Dogs—A Cross Sectional Study of 364 Dogs

veterinary sciences Article Trauma-Associated Pulmonary Laceration in Dogs—A Cross Sectional Study of 364 Dogs Giovanna Bertolini 1,* , Chiara Briola 1, Luca Angeloni 1, Arianna Costa 1, Paola Rocchi 2 and Marco Caldin 3 1 Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology Division, San Marco Veterinary Clinic and Laboratory, via dell’Industria 3, 35030 Veggiano, Padova, Italy; [email protected] (C.B.); [email protected] (L.A.); [email protected] (A.C.) 2 Intensive Care Unit, San Marco Veterinary Clinic and Laboratory, via dell’Industria 3, 35030 Veggiano, Padova, Italy; [email protected] 3 Clinical Pathology Division, San Marco Veterinary Clinic and Laboratory, via dell’Industria 3, 35030 Veggiano, Padova, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-0498561098 Received: 5 March 2020; Accepted: 8 April 2020; Published: 12 April 2020 Abstract: In this study, we describe the computed tomography (CT) features of pulmonary laceration in a study population, which included 364 client-owned dogs that underwent CT examination for thoracic trauma, and compared the characteristics and outcomes of dogs with and without CT evidence of pulmonary laceration. Lung laceration occurred in 46/364 dogs with thoracic trauma (prevalence 12.6%). Dogs with lung laceration were significantly younger than dogs in the control group (median 42 months (interquartile range (IQR) 52.3) and 62 months (IQR 86.1), respectively; p = 0.02). Dogs with lung laceration were significantly heavier than dogs without laceration (median 20.8 kg (IQR 23.3) and median 8.7 kg (IQR 12.4 kg), respectively p < 0.0001). When comparing groups of dogs with thoracic trauma with and without lung laceration, the frequency of high-energy motor vehicle accident trauma was more elevated in dogs with lung laceration than in the control group. -

ABCDE Approach

The ABCDE and SAMPLE History Approach Basic Emergency Care Course Objectives • List the hazards that must be considered when approaching an ill or injured person • List the elements to approaching an ill or injured person safely • List the components of the systematic ABCDE approach to emergency patients • Assess an airway • Explain when to use airway devices • Explain when advanced airway management is needed • Assess breathing • Explain when to assist breathing • Assess fluid status (circulation) • Provide appropriate fluid resuscitation • Describe the critical ABCDE actions • List the elements of a SAMPLE history • Perform a relevant SAMPLE history. Essential skills • Assessing ABCDE • Needle-decompression for tension • Cervical spine immobilization pneumothorax • • Full spine immobilization Three-sided dressing for chest wound • • Head-tilt and chin-life/jaw thrust Intravenous (IV) line placement • • Airway suctioning IV fluid resuscitation • • Management of choking Direct pressure/ deep wound packing for haemorrhage control • Recovery position • Tourniquet for haemorrhage control • Nasopharyngeal (NPA) and oropharyngeal • airway (OPA) placement Pelvic binding • • Bag-valve-mask ventilation Wound management • • Skin pinch test Fracture immobilization • • AVPU (alert, voice, pain, unresponsive) Snake bite management assessment • Glucose administration Why the ABCDE approach? • Approach every patient in a systematic way • Recognize life-threatening conditions early • DO most critical interventions first - fix problems before moving on -

Pre and Post-Thoracostomy Chest X-Ray Taking; Do We Must Do?

www.revhipertension.com Revista Latinoamericana de Hipertensión. Vol. 15 - Nº 1, 2020 Pre and post-thoracostomy chest x-ray taking; do we must do? 71 Radiografía de tórax antes y después de la toracostomía; Qué debemos hacer? Salaminia, Shirvan; Talebi, Shadi; Mehrabi, Saadat 1Assistant Professor of Cardiac Surgery, Clinical Research Development Unit Beheshti Hospital, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran. [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. 2General Practitioner, Clinical Research Development Unit Beheshti Hospital, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran. 3Assistant Professor of Thoracic Surgery, Clinical Research Development Unit Beheshti Hospital, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran *corresponding author: Saadat Mehrabi, Assistant Professor of Thoracic Surgery, Clinical Research Development Unit Beheshti Hospital, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran. Email: [email protected] https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4074244 Abstract he prevalence of collision accidents is high in Results: Of the 58 chest tubes with the indication for re- Iran, a developing country. Currently, a plain moval, only one patient needed further observation clini- chest radiograph is routine 6 to 8 hours af- cally after removal. The coincident chest x-ray (CXR) led to ter chest tube removal. In recent years, there have been recurrent chest tube insertion. All thoracostomies had per- doubts about the necessity of routine post-removal chest formed by a trained resident or surgeon. Considering vari- x-ray (CXR) in the absence of clinical symptoms. In chil- able clinical decisions, a comparison of the diagnostic value dren, this is especially imperative because they are more of chest x-ray (CXR) to clinical examination did not differ sensitive to radiation exposure. -

Iatrogenic Tension Pneumothorax After Surgical Tracheostomy in a Child with Idiopathic Subglottic Stenosis - Case Report

Kosin Medical Journal 2019;34:161-167. https://doi.org/10.7180/kmj.2019.34.2.161 &D VH 5HSRUWV Iatrogenic Tension Pneumothorax after Surgical Tracheostomy in a Child with Idiopathic Subglottic Stenosis - case report Sang Yoong Park, Woo jae Yim, Joon Ho Jeong, Jeongho Kim, Seung-Cheol Lee, So Ron Choi, Jong-Hwan Lee, Chan Jong Chung Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Dong-A University College of Medicine, Busan, Korea Tracheostomy is increasingly performed in children for upper airway anomalies. Here, an 18-month-old child (height 84.1 cm, weight 12.5 kg) presented to the emergency department with dyspnea, stridor, and chest retraction. However, exploration of the airways using a bronchoscope failed due to subglottic stenosis. Therefore, a surgical tracheostomy was successfully performed with manual mask ventilation. However, pneumomediastinum was found in the postoperative chest radiograph. Although an oxygen saturation of 99% was initially maintained, oxygen saturation levels dropped, due to sudden dyspnea, after 3 hours. A chest radiograph taken at this time revealed a left tension pneumothorax and small right pneumothorax. Despite a needle thoracostomy, the pneumothorax was aggravated, and cardiac arrest occurred. Car - diopulmonary-cerebral resuscitation was performed, but the patient was declared dead 30 minutes later. This study high - lights the fatal complications that can occur in children during tracheostomy. Therefore, close monitoring, immediate suspicion, recognition, and aggressive management may avoid fatal outcomes. Key Words : Pediatrics, Pneumomediastinum, Tension pneumothorax, Tracheostomy, Thoracostomy Tracheostomy is increasingly being performed swallowing problems, some of which can be in children, leading to improvements in neonatal life-threatening in children. -

Complications Associated with the Use of Autologous Costal Cartilage

Rhinoplasty Aesthetic Surgery Journal 2015, Vol 35(6) 644–652 Complications Associated With the Use © 2015 The American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, Inc. Reprints and permission: of Autologous Costal Cartilage in Rhinoplasty: [email protected] DOI: 10.1093/asj/sju117 A Systematic Review www.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com Kiran Varadharajan, MRCS, DOHNS; Priya Sethukumar, MRCS (ENT); Mohiemen Anwar, MRCS, DOHNS; and Kalpesh Patel, FRCS Abstract Background: Autologous costal cartilage grafts are common in rhinoplasty. To date, no formal systematic review of complications associated with autol- ogous costal cartilage grafting in rhinoplasty exists. Objectives: The authors review current literature to examine the rates of donor and recipient site complications associated with autologous costal carti- lage in rhinoplasty. Methods: Databases (EMBASE, PubMed, MEDLINE, and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews) and references of pertinent articles were searched between January 1980 to July 2014 to find studies evaluating rates of complications with autologous costal cartilage grafting in rhinoplasty. These studies were then screened with specific inclusion/exclusion criteria, and data were extracted from included studies and pooled for analysis. Results: A total of 21 eligible studies were included. Pooled donor site complication incidence was pneumothorax (0.1%), pleural tear (0.6%), infection (0.6%), seroma (0.6%), scar-related problems (2.9%), and severe donor site pain (0.2%). Pooled recipient site complications were as follows: warping (5.2%), infection (2.5%), displacement/extrusion (0.6%), graft fracture (0.2%), and graft resorption (0.9%). Conclusions: Autologous costal rhinoplasty remains a safe procedure, but is associated with not insignificant rates of minor recipient site complications, such as warping. -

Resident Handbook

Duke OHNS Residency Program Handbook Table of Contents • Call Schedules • Communication (Important Numbers) • Compact Between Resident Physicians and Their Teachers • Conference Schedule • Conference Travel Policy • Copier/Fax/Supplies • Core Tenets of Residency Education • Corrective Action and Hearing Procedures • Duty Hour/Fatigue Policy • Extended Leave of Absence • Evaluations • Faculty Supervision Policy • Grievance Policy • Handoff Policy • Harassment Policy • Conflict Resolution • Impairment Policy • Institutional Compliance Modules • Lab Coats/Prescriptions Pads • Leave of Absence Policy • Licensure Requirements • Mailbox and Messages • Society Membership • Otolaryngology In-Training Exam • Required Reading • Home Study Course • ABOto Self-Assessment Modules (SAM) • Moonlighting • Unassigned Patients • Operative Case Logs • Case Coding Guidelines • Overall Policies for Duke University Residents • Policy on Resident Educational Progression and Goals & Objectives • Professionalism • Record Keeping • Reimbursement Policy • Resident Appointment, Reappointment, Promotion and Dismissal • Resident Education Fund • Resident Mentor Program • Supervisory Lines of Responsibility • Surgical Case Review/M&M/QA Conference • Vacation Policy • USMLE Step 3 • Duke Regional Coverage • Duke Raleigh Coverage Compact Between Resident Physicians and Their Teachers Residency is an integral component of the formal education of physicians. In order to practice medicine independently, physicians must receive a medical degree and complete a supervised period of residency training in a specialty area. To meet their educational goals, Resident physicians must participate actively in the care of patients and must assume progressively more responsibility for that care as they advance through their training. In supervising Resident education, Faculty must ensure that trainees acquire the knowledge and special skills of their respective disciplines while adhering to the highest standards of quality and safety in the delivery of patient care services. -

The Greenville Voice Center

The Greenville Voice Center What to Expect: Microlaryngoscopy What is microlaryngoscopy? Surgical microdirect laryngoscopy (MDL) involves putting a hollow metal tube or pipe (called a laryngoscope) into the mouth and down the throat to look at the larynx and the vocal folds. You will be asleep so that you are comfortable. We put a tooth guard over your teeth or a soft pad over your gums if you do not have teeth to protect them from the metal tube. We usually use a microscope or magnifying telescope to allow us to see the vocal cords at high magnification. Thus, the term micro-direct laryngoscopy: we’re using a microscope to look directly at the larynx. Bronchoscopy involves placing a camera between the vocal folds and passing it through the larynx into the airways to look at the trachea and the air passages to the lungs. Esophagoscopy involves placing a metal tube with a camera behind the larynx into the esophagus (swallowing pipe) in order to look at it throughout its length, sometimes as far as the stomach. The day of surgery: The day begins in the preoperative area where you will check in, meet the anesthesia team and OR nurses, speak with me, and have an IV placed in your arm or hand. When it is time for surgery, you will roll back into the operating room where you will see our team there. The instruments will likely be out and waiting for you. Once everything is confirmed and the safety checks are done, the anesthesia team will begin to put you to sleep. -

Advances in Chest Drain Management in Thoracic Disease

Review Article Advances in chest drain management in thoracic disease Robert S. George, Kostas Papagiannopoulos St. James’s University Hospital, Leeds, UK Contributions: (I) Conception and design: None; (II) Administrative support: None; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: None; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: None; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: None; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Mr. Kostas Papagiannopoulos, MD (CTh), MMed Thorax. St. James’s University Hospital, Department of Thoracic Surgery, Level 3 Bexley Wing, Beckett Street, LS9 7TF, Leeds, UK. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: An adequate chest drainage system aims to drain fluid and air and restore the negative pleural pressure facilitating lung expansion. In thoracic surgery the post-operative use of the conventional underwater seal chest drainage system fulfills these requirements, however they allow great variability amongst practices. In addition they do not offer accurate data and they are often inconvenient to both patients and hospital staff. This article aims to simplify the myths surrounding the management of chest drains following chest surgery, review current experience and explore the advantages of modern digital chest drain systems and address their disease-specific use. Keywords: Chest tube; intercostal drain (ICD); digital devices; air leak; pleural effusion Submitted Oct 15, 2015. Accepted for publication Oct 27, 2015. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.11.19 View this article at: http://dx.doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.11.19 Introduction Historical background The pleural cavity is an air-tight closed space that contains In 1965 Hughes advocated the use of closed tube a small amount of pleural fluid. -

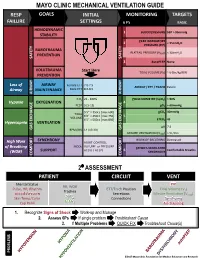

Mechanical Ventilation Guide

MAYO CLINIC MECHANICAL VENTILATION GUIDE RESP GOALS INITIAL MONITORING TARGETS FAILURE SETTINGS 6 P’s BASIC HEMODYNAMIC 1 BLOOD PRESSURE SBP > 90mmHg STABILITY PEAK INSPIRATORY 2 < 35cmH O PRESSURE (PIP) 2 BAROTRAUMA PLATEAU PRESSURE (P ) < 30cmH O PREVENTION PLAT 2 SAFETY SAFETY 3 AutoPEEP None VOLUTRAUMA Start Here TIDAL VOLUME (V ) ~ 6-8cc/kg IBW PREVENTION T Loss of AIRWAY Female ETT 7.0-7.5 AIRWAY / ETT / TRACH Patent Airway MAINTENANCE Male ETT 8.0-8.5 AIRWAY AIRWAY FiO2 21 - 100% PULSE OXIMETRY (SpO2) > 90% Hypoxia OXYGENATION 4 PEEP 5 [5-15] pO2 > 60mmHg 5’5” = 350cc [max 600] pCO2 40mmHg TIDAL 6’0” = 450cc [max 750] 5 VOLUME 6’5” = 500cc [max 850] ETCO2 45 Hypercapnia VENTILATION pH 7.4 GAS GAS EXCHANGE BPM (RR) 14 [10-30] GAS EXCHANGE MINUTE VENTILATION (VMIN) > 5L/min SYNCHRONY WORK OF BREATHING Decreased High Work ASSIST CONTROL MODE VOLUME or PRESSURE of Breathing PATIENT-VENTILATOR AC (V) / AC (P) 6 Comfortable Breaths (WOB) SUPPORT SYNCHRONY COMFORT COMFORT 2⁰ ASSESSMENT PATIENT CIRCUIT VENT Mental Status PIP RR, WOB Pulse, HR, Rhythm ETT/Trach Position Tidal Volume (V ) Trachea T Blood Pressure Secretions Minute Ventilation (V ) SpO MIN Skin Temp/Color 2 Connections Synchrony ETCO Cap Refill 2 Air-Trapping 1. Recognize Signs of Shock Work-up and Manage 2. Assess 6Ps If single problem Troubleshoot Cause 3. If Multiple Problems QUICK FIX Troubleshoot Cause(s) PROBLEMS ©2017 Mayo Clinic Foundation for Medical Education and Research CAUSES QUICK FIX MANAGEMENT Bleeding Hemostasis, Transfuse, Treat cause, Temperature control HYPOVOLEMIA Dehydration Fluid Resuscitation (End points = hypoxia, ↑StO2, ↓PVI) 3rd Spacing Treat cause, Beware of hypoxia (3rd spacing in lungs) Pneumothorax Needle D, Chest tube Abdominal Compartment Syndrome FLUID Treat Cause, Paralyze, Surgery (Open Abdomen) OBSTRUCTED BLOOD RETURN Air-Trapping (AutoPEEP) (if not hypoxic) Pop off vent & SEE SEPARATE CHART PEEP Reduce PEEP Cardiac Tamponade Pericardiocentesis, Drain. -

Management of Patient with Chest Drainage Unit Online Exam

GMHA NURSING SERVICES DEPARTMENT Guidelines for Care: Management of Patients with a Chest Drainage Unit Loribelle Kim, RNC‐OB, Staff Nurse Training Officer‐ Acting OBJECTIVES: 1. Identify the indications, contraindications, and risks associated with the use of a Chest tube/Chest Drainage Unit. 2. Identify and be familiar with the Chest Drainage Units available in your designated unit. 3. Recall basic principles of the Chest Drainage Units (CDUs). 4. Recall Nursing Staff roles/responsibilities for patients with a chest tube and Chest Drainage Unit. 5. Recall special considerations and KEY POINTS while patient is on a Chest Drainage Unit. 6. Review GMHA Policy and Procedure 6353-11-H-14: Care of a Patient with a Thoracic Drainage System and 6313-II-51.00: Care of the patient with Chest Tubes WHAT ARE INDICATIONS FOR A PATIENT WITH A CHEST TUBE DRAINAGE SYSTEM? A Chest Drainage Unit (CDU) (also known as the Thoracic drainage system) is a device that is connected to a tube that is inserted into the pleural space of the chest to evacuate air or fluid and/or help regain negative pressure. 1. During or immediately after thoracic surgery, chest tubes are positioned strategically in the pleural space, sutured to the skin, and connected to the CDU to remove the residual air, and fluid from the pleural or mediastinal space. 2. CDUs are also inserted to treat spontaneous pneumothorax or hemothorax/pneumothorax caused by trauma. INDICATIONS CONTINUED… 3. CDUs help drain substances that may accumulate in the lungs such as: AIR- Pnuemothorax BLOOD- Hemothorax FLUID- Pleural effusion LYMPHATIC FLUID- Chylothorax PUS- Emphyema This collection of air, fluid, or other substances in the thoracic cavity can compromise cardiopulmonary function and cause collapse of the lung. -

Chest-Tube Insertion

T h e new england journal o f medicine videos in clinical medicine Chest-Tube Insertion Shelly P. Dev, M.D., Bartolomeu Nascimiento, Jr., M.D., Carmine Simone, M.D., and Vincent Chien, M.D. Indications Insertion of a chest tube is indicated in either emergency or nonemergency situa- From the Department of Critical Care Med- tions. Specific indications are listed in Table 1.1-3 icine, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, University of Toronto, Toronto. Address reprint requests to Dr. Dev at the Depart- Contraindications ment of Critical Care, Sunnybrook Health Published guidelines state that there are no absolute contraindications for drainage Sciences Centre, 2075 Bayview Ave., Office 1 D-112, Toronto, ON M4N 3M5, Canada, by means of a chest tube except when a lung is completely adherent to the chest or [email protected]. wall throughout the hemithorax.2 Relative contraindications include a risk of bleed- ing in patients taking anticoagulant medication or in patients with a predisposition N Engl J Med 2007;357:e15. Copyright © 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. to bleeding or abnormal clotting profiles. Whenever possible, coagulopathies and platelet defects should be corrected with the infusion of blood products, such as fresh frozen plasma and platelets. Equipment Most hospitals have presterilized, packaged chest-tube–insertion trays. The key com- ponents of the tray are a scalpel with size 11 blade; several dissecting instruments, such as curved Kelly clamps or artery forceps; a 10-ml syringe and a 20-ml syringe; one small-gauge needle (size 25) and one larger-gauge needle for deeper anesthetic infiltration (size 18–21); a needle driver; scissors; one packet of strong, nonabsorb- able, curved sutures of size 1.0 or larger, made from silk or nylon4; and a chest tube of appropriate size (see below). -

Large Traumatic Pneumatocele in a 2-Year-Old Child

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Case Reports in Pediatrics Volume 2013, Article ID 940189, 3 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/940189 Case Report Large Traumatic Pneumatocele in a 2-Year-Old Child N. K. Cheung,1 A. James,2 and R. Kumar3 1 Department of Surgery, John Hunter Hospital, New Lambton Heights, Newcastle, NSW 2305, Australia 2 Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, John Hunter Hospital, New Lambton Heights, Newcastle, NSW 2305, Australia 3 Department of Paediatric Surgery, John Hunter Children’s Hospital, New Lambton Heights, Newcastle, NSW 2305, Australia Correspondence should be addressed to R. Kumar; [email protected] Received 3 August 2013; Accepted 22 August 2013 Academic Editors: Y. Z. Bai, S. Burjonrappa, S. G. Golombek, and Z. Jiang Copyright © 2013 N. K. Cheung et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Traumatic pneumatoceles are a rare complication of blunt chest trauma in children. Although they characteristically present as small, regular shaped lesions which can be safely treated nonoperatively, larger traumatic pneumatoceles pose diagnostic and management difficulties for clinicians. This case study reports one of the largest traumatic pneumatoceles reported to datein the paediatric population, which resulted in aggressive surgical intervention for both diagnostic and treatment reasons. This case adds further evidence to the current literature that significantly large traumatic pneumatoceles with failure of initial conservative management warrant surgical exploration and management to optimise recovery and prevent complications. 1. Introduction 2. Case Presentation Traumatic pneumatocele (TP) is a rare condition occurring A 2-year-old boy presented to the emergency department after blunt chest trauma in children and young adults, after being knocked over and his left shoulder and chest accounting for 3.9% of paediatric blunt chest traumas.