Tectonic Plate Movements and Hotspots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

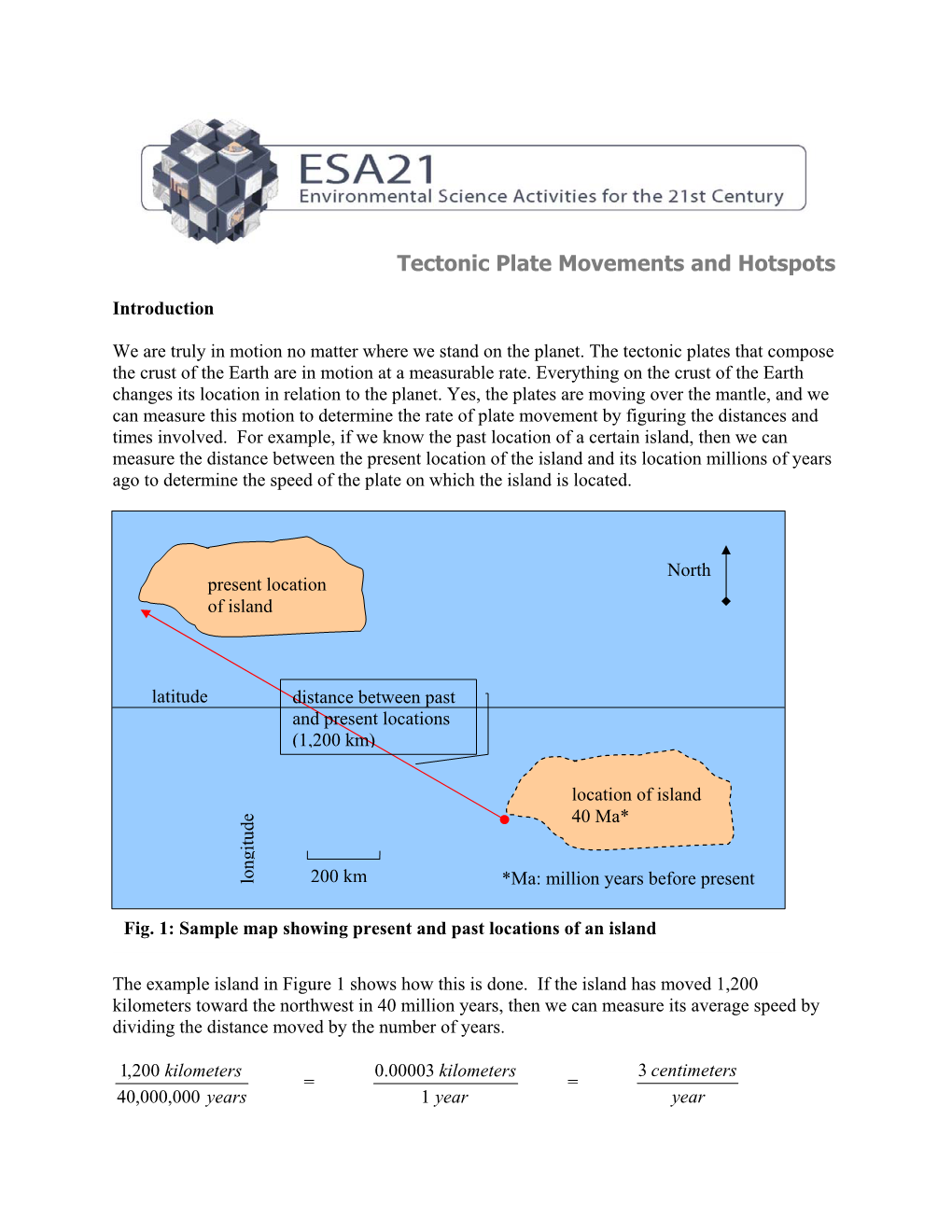

Hot Spots and Plate Movement Exercise

Name(s) Hot Spots and Plate Movement exercise Two good examples of present-day hot spot volcanism, as derived from mantle plumes beneath crustal plates, are Kilauea, Hawaii (on the Pacific oceanic plate) and Yellowstone (on the continental North American plate). These hot spots have produced a chain of inactive volcanic islands or seamounts on the Pacific plate (Fig. 1) and volcanic calderas or fields on the North American plate (Fig. 2) – see the figures below. Figure 1. Chain of islands and seamounts produced by the Hawaiian hot spot. Figure 2. Chain of volcanic fields produced by the Yellowstone hot spot. The purposes of this exercise are to use locations, ages, and displacements for each of these hot spot chains to determine 1. Absolute movement directions, and 2. Movement rates for both the Pacific and western North American plates, and then to use this information to determine 3. Whether the rates and directions of the movement of these two plates have been the same or different over the past 16 million years. This exercise uses the Pangaea Breakup animation, which is a KML file that runs in the standalone Google Earth application. To download the Pangaea Breakup KML file, go here: http://csmgeo.csm.jmu.edu/Geollab/Whitmeyer/geode/pangaeaBreakup /PangaeaBreakup.kml To download Google Earth for your computer, go here: https://www.google.com/earth/download/ge/agree.html Part 1. Hawaiian Island Chain Load the PangaeaBreakup.kml file in Google Earth. Make sure the time period in the upper right of the screen says “0 Ma” and then select “Hot Spot Volcanos” under “Features” in the Places menu on the left of the screen. -

Cenozoic Changes in Pacific Absolute Plate Motion A

CENOZOIC CHANGES IN PACIFIC ABSOLUTE PLATE MOTION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI`I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN GEOLOGY AND GEOPHYSICS DECEMBER 2003 By Nile Akel Kevis Sterling Thesis Committee: Paul Wessel, Chairperson Loren Kroenke Fred Duennebier We certify that we have read this thesis and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science in Geology and Geophysics. THESIS COMMITTEE Chairperson ii Abstract Using the polygonal finite rotation method (PFRM) in conjunction with the hotspot- ting technique, a model of Pacific absolute plate motion (APM) from 65 Ma to the present has been created. This model is based primarily on the Hawaiian-Emperor and Louisville hotspot trails but also incorporates the Cobb, Bowie, Kodiak, Foundation, Caroline, Mar- quesas and Pitcairn hotspot trails. Using this model, distinct changes in Pacific APM have been identified at 48, 27, 23, 18, 12 and 6 Ma. These changes are reflected as kinks in the linear trends of Pacific hotspot trails. The sense of motion and timing of a number of circum-Pacific tectonic events appear to be correlated with these changes in Pacific APM. With the model and discussion presented here it is suggested that Pacific hotpots are fixed with respect to one another and with respect to the mantle. If they are moving as some paleomagnetic results suggest, they must be moving coherently in response to large-scale mantle flow. iii List of Tables 4.1 Initial hotspot locations . -

The Plate Tectonics of Cenozoic SE Asia and the Distribution of Land and Sea

Cenozoic plate tectonics of SE Asia 99 The plate tectonics of Cenozoic SE Asia and the distribution of land and sea Robert Hall SE Asia Research Group, Department of Geology, Royal Holloway University of London, Egham, Surrey TW20 0EX, UK Email: robert*hall@gl*rhbnc*ac*uk Key words: SE Asia, SW Pacific, plate tectonics, Cenozoic Abstract Introduction A plate tectonic model for the development of SE Asia and For the geologist, SE Asia is one of the most the SW Pacific during the Cenozoic is based on palaeomag- intriguing areas of the Earth$ The mountains of netic data, spreading histories of marginal basins deduced the Alpine-Himalayan belt turn southwards into from ocean floor magnetic anomalies, and interpretation of geological data from the region There are three important Indochina and terminate in a region of continen- periods in regional development: at about 45 Ma, 25 Ma and tal archipelagos, island arcs and small ocean ba- 5 Ma At these times plate boundaries and motions changed, sins$ To the south, west and east the region is probably as a result of major collision events surrounded by island arcs where lithosphere of In the Eocene the collision of India with Asia caused an the Indian and Pacific oceans is being influx of Gondwana plants and animals into Asia Mountain building resulting from the collision led to major changes in subducted at high rates, accompanied by in- habitats, climate, and drainage systems, and promoted dis- tense seismicity and spectacular volcanic activ- persal from Gondwana via India into SE Asia as well -

Geoscenario Introduction: Yellowstone Hotspot Yellowstone Is One of America’S Most Beloved National Parks

Geoscenario Introduction: Yellowstone Hotspot Yellowstone is one of America’s most beloved national parks. Did you know that its unique scenery is the result of the area’s geology? Yellowstone National Park lies in a volcanic Hydrothermal Features caldera, an area that collapsed after an Hot springs are naturally warm bodies of eruption. Below the caldera is a hotspot. water. Hot magma heats water underground There, huge amounts of magma sit just below to near boiling. Some organisms still manage Earth’s surface. In this geoscenario, you’ll to live in these springs. learn some of the geologic secrets that make Yellowstone such a special place. Its vivid colors and huge size make Grand Prismatic www.fossweb.com Spring the most photographed feature at Yellowstone. Extremely hot water rises 37 m from a crack in Earth’s crust to form this hot spring. permission. further Berkeley without use California of classroom University than the of other use or Regents The redistribution, Copyright resale, for Investigation 8: Geoscenarios 109 2018-2019 Not © 1558514_MSNG_Earth History_Text.indd 109 11/29/18 3:15 PM The water in mud pots tends to be acidic. Hotspot Theory It dissolves the surrounding rock. Hot water Most earthquakes and volcanic eruptions mixes with the dissolved rock to create occur near plate boundaries, but there are bubbly pots. some exceptions. In 1963, John Tuzo Wilson Other hydrothermal features include (1908–1993) came up with a theory for these fumaroles and geysers. Fumaroles exceptions. He described stationary magma are cracks that allow steam to escape chambers beneath the crust. -

The Kerguelen Plume: What We Have Learned from ~120 Myr of Volcanism

The Kerguelen Plume: What We Have Learned From ~120 Myr of Volcanism F.A. Frey (1) and D. Weis (2) (1) Earth Atmospheric & Planetary Sciences, MIT, Cambridge, MA 02139, (2) EOS, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6T1Z4 The Kerguelen Plume has had a major role in creating major volcanic features in the Eastern Indian Ocean over the last ~120 myr. In order to understand this role, igneous basement has been drilled and cored at 9 sites on the Kerguelen Plateau, 2 sites on Broken Ridge and 7 sites on the Ninetyeast Ridge(1,2,3,4). In addition, stratigraphic volcanic sections on the two relatively young islands (Kerguelen and Heard) constructed on the Kerguelen Plateau have been studied(5,6), as well as dredged samples from seamounts defining a linear trend between these islands(7). Major results are: (a) The Kerguelen Plateau began forming at ~120 Ma, after Gondwana breakup. Eruption ages decrease from ~120 Ma in the southern plateau to ~95 Ma in the central plateau. This age range is not consistent with a pulse of volcanism associated with melting of a single, large plume head. (b) The sampled volcanic portion of the plateau is dominantly tholeiitic basalt that formed islands, but the waning stage of volcanism included alkalic basalt and highly evolved, explosively erupted trachytes and rhyolites. (c) At several geographically dispersed locations on the plateau, the Cretaceous tholeiitic basalt has been contaminated by a component derived from continental crust. Geophysical data are consistent with continental crust in the oceanic lithosphere and clasts of ancient garnet-biotite gneiss occur in a conglomerate intercalated with basalt on Elan Bank. -

Deep Structure of the Northern Kerguelen Plateau and Hotspot

Philippe Charvis,l Maurice Recq,2 Stéphane Operto3 and Daniel Brefort4 'ORSTOM (UR 14), Obsematoire Ocinnologiq~~ede Ville~rnnche-srir.mer, BP 4S, 06230 Villefmnche-sitr-mer, Fronce 'Doniaines océoniqiies (LIRA 1278 dir CNRS & GDR 'CEDO'), UFR des Sciences et Techniqites, Universite de Bretagne Occidentale, BP S09, 6 Aveme Le Gorgeit, 29285 Brest Cedex, France 3Laboratoire de Céodyrrnniiqire soils-marine, GEMCO, (URA 718 dir CNRS), Observatoire Océanologiqite de Villefranche-snr-mer, BP 45, 062320 Villefranclie-sur-nier, France 41nsfitici de Physique dii Globe de Paris, Laboratoire de Sismologie (LA195 du CNRS), Boîte 89, 4 place Jiissieit, 15252 Paris Cedex 05, France Accepted 1995 ?larch 10. Received 1995 March 10; in original form 1993 June 16 SUMMARY Seismic refraction profiles were carried out in 1983 and 1987 throughout the Kerguelen Isles (southern Indian Ocean, Terres Australes & Antarctiques Françaises, TAAF) and thereafter at sea on the Kerguelen-Heard Plateau during the MD66/KeOBS cruise in 1991. These profiles substantiate the existence of oceanic-type crust beneath the Kerguelen-Heard Plateau stretching from 46"s to SOS, including the archipelago. Seismic velocities within both structures are in the range of those encountered in 'standard' oceanic crust. However, the Kerguelen Isles and the Kerguelen-Heard Plateau differ strikingly in their velocity-depth structure. Unlike the Kerguelen Isles, the .thickening of the crust below the Kerguelen-Heard Plateau is caused by a 17km thick layer 3. Velocities of 7.4 km s-I or so Lvithin the transition to mantle zone below the Kerguelen Isles are ascribed to the lower crust intruded and/or underplated by upper mantle material. -

Vulnerability of Biodiversity Hotspots to Global Change

Global Ecology and Biogeography, (Global Ecol. Biogeogr.) (2014) bs_bs_banner RESEARCH Vulnerability of biodiversity hotspots to PAPER global change Céline Bellard1*, Camille Leclerc1, Boris Leroy1,2,3, Michel Bakkenes4, Samuel Veloz5, Wilfried Thuiller6 and Franck Courchamp1 1Écologie, Systématique & Évolution, UMR ABSTRACT CNRS 8079, Université Paris-Sud, F-91405 Aim Global changes are predicted to have severe consequences for biodiversity; 34 Orsay Cedex, France, 2EA 7316 Biodiversité et Gestion des Territoires, Université de Rennes 1, biodiversity hotspots have become international priorities for conservation, with Campus de Beaulieu, 35042 Rennes Cedex, important efforts allocated to their preservation, but the potential effects of global 3Service du Patrimoine Naturel, MNHN, changes on hotspots have so far received relatively little attention. We investigate Paris, France, 4Netherlands Environmental whether hotspots are quantitatively and qualitatively threatened to the same order Assessment Agency (PBL), PO Box 303, 3720 of magnitude by the combined effects of global changes. 5 Bilthoven, The Netherlands, PRBO Location Worldwide, in 34 biodiversity hotspots. Conservation Science, 3820 Cypress Dr. #11, Petaluma, CA 94954, USA, 6Laboratoire Methods We quantify (1) the exposure of hotspots to climate change, by estimat- d’Ecologie Alpine, UMR CNRS 5553, ing the novelty of future climates and the disappearance of extant climates using Université Joseph Fourier, Grenoble 1, BP 53, climate dissimilarity analyses, (2) each hotspot’s vulnerability to land modification FR-38041 Grenoble Cedex 9, France and degradation by quantifying changes in land-cover variables over the entire habitat, and (3) the future suitability of distribution ranges of ‘100 of the world’s worst invasive alien species’, by characterizing the combined effects of climate and land-use changes on the future distribution ranges of these species. -

Seismic Tomography Constraints on Reconstructing

SEISMIC TOMOGRAPHY CONSTRAINTS ON RECONSTRUCTING THE PHILIPPINE SEA PLATE AND ITS MARGIN A Dissertation by LINA HANDAYANI Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2004 Major Subject: Geophysics SEISMIC TOMOGRAPHY CONSTRAINTS ON RECONSTRUCTING THE PHILIPPINE SEA PLATE AND ITS MARGIN A Dissertation by LINA HANDAYANI Submitted to Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved as to style and content by: Thomas W. C. Hilde Mark E. Everett (Chair of Committee) (Member) Richard L. Gibson David W. Sparks (Member) (Member) William R. Bryant Richard L. Carlson (Member) (Head of Department) December 2004 Major Subject: Geophysics iii ABSTRACT Seismic Tomography Constraints on Reconstructing the Philippine Sea Plate and Its Margin. (December 2004) Lina Handayani, B.S., Institut Teknologi Bandung; M.S., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Thomas W.C. Hilde The Philippine Sea Plate has been surrounded by subduction zones throughout Cenozoic time due to the convergence of the Eurasian, Pacific and Indian-Australian plates. Existing Philippine Sea Plate reconstructions have been made based primarily on magnetic lineations produced by seafloor spreading, rock magnetism and geology of the Philippine Sea Plate. This dissertation employs seismic tomography model to constraint the reconstruction of the Philippine Sea Plate. Recent seismic tomography studies show the distribution of high velocity anomalies in the mantle of the Western Pacific, and that they represent subducted slabs. Using these recent tomography data, distribution maps of subducted slabs in the mantle beneath and surrounding the Philippine Sea Plate have been constructed which show that the mantle anomalies can be related to the various subduction zones bounding the Philippine Sea Plate. -

Mantle Plumes and Their Role in Earth Processes

REVIEWS Mantle plumes and their role in Earth processes Anthony A. P. Koppers 1 ✉ , Thorsten W. Becker 2, Matthew G. Jackson 3, Kevin Konrad 1,4, R. Dietmar Müller 5, Barbara Romanowicz6,7,8, Bernhard Steinberger 9,10 and Joanne M. Whittaker 11 Abstract | The existence of mantle plumes was first proposed in the 1970s to explain intra-plate, hotspot volcanism, yet owing to difficulties in resolving mantle upwellings with geophysical images and discrepancies in interpretations of geochemical and geochronological data, the origin, dynamics and composition of plumes and their links to plate tectonics are still contested. In this Review, we discuss progress in seismic imaging, mantle flow modelling, plate tectonic reconstructions and geochemical analyses that have led to a more detailed understanding of mantle plumes. Observations suggest plumes could be both thermal and chemical in nature, can attain complex and broad shapes, and that more than 18 plumes might be rooted in regions of the lowermost mantle. The case for a deep mantle origin is strengthened by the geochemistry of hotspot volcanoes that provide evidence for entrainment of deeply recycled subducted components, primordial m an tle domains and, potentially, materials from Earth’s core. Deep mantle plumes often appear deflected by large-scale mantle flow, resulting in hotspot motions required to resolve past tectonic plate motions. Future research requires improvements in resolution of seismic tomography to better visualize deep mantle plume structures at smaller than 100-km scales. Concerted multi-proxy geochemical and dating efforts are also needed to better resolve spatiotemporal and chemical evolutions of long-lived mantle plumes. -

Oxygen Fugacity of Hotspot Xenoliths: a Window Into the Earth's Mantle

Oxygen fugacity of hotspot xenoliths: A window into the Earth’s mantle Kellie Wall1,2, Fred Davis1, and Elizabeth Cottrell1 1Department of Mineral Sciences, Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC 2School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Washington State University, Pullman, WA Introduction Results Discussion Mantle xenoliths—chunks of the Earth’s Peridotite xenoliths recorded fO2 ranges of -1.4 to 0.9 (Savai’i), 0.6 to 0.7 (Tahiti), and -1.0 to 0.2 We observe an intriguing dichotomy in apparent fO2 between spinels of different habit interior carried to the surface by volcanic (Tubuai) log units relative to the quartz-fayalite-magnetite (QFM) buffer (Fig. 9). These values are within a single sample. In these samples, there is no indication that melt has interacted eruptions—provide a rare glimpse into the within the range of oxygen fugacities for peridotites from other tectonic settings: more oxidized than with the rock. We hypothesize that an increase in temperature induced by lithosphere- those from ridges but more reduced than those from subduction zones. Within some samples we plume interaction has resulted in major element diffusion and an apparent shift in fO . We chemistry of the deep Earth (Fig. 1). Of 2 observe two trends: TiO2 increasing with fO2, and a link between fO2 and spinel habit, such that fine, suggest that these xenoliths erupted before the interiors of large spinels could diffusively particular interest is the oxygen fugacity “wispy” spinel records higher apparent fO2 than large blocky grains. reequilibrate. O (f 2; the effective ‘partial pressure’ of An outstanding mystery in the fO2 realm is that ridge peridotites are an order of xenoliths’ magnitude more reduced than lavas erupted at ridges. -

How Volcanoes Formed the Hawaiian Islands by National Geographic Society, Adapted by Newsela Staff on 03.09.20 Word Count 723 Level 870L

How volcanoes formed the Hawaiian Islands By National Geographic Society, adapted by Newsela staff on 03.09.20 Word Count 723 Level 870L A volcano explodes in Hawaii. Photo by: National Geographic Hawaii is the world's most remote island population center in the world. The six largest Hawaiian Islands are the Big Island, Maui, Lanai, Molokai, Oahu and Kauai. They form a chain of islands running to the northwest. The islands appear in this pattern because they are on a volcanic hotspot. A hotspot is an area in the Earth's mantle where plumes of hot molten rock called magma rise up, forming volcanos on the Earth's crust. The crust is the outermost layer of a planet. The mantle is the layer below the crust. This process happened with the Hawaiian Islands. They formed one after the other. A tectonic plate slid over magma, creating a volcano. The plate continued to move over the hotspot, and the active volcano lost its connection to the hotspot and became inactive. A new active volcano formed from the hotspot. The processed continued. Understanding Tectonic Plates This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. Volcano hotspots can happen in the middle of tectonic plates. That's unlike other volcano activity, which takes place at plate boundaries. Scientists think that volcano hotspots might happen near unusually hot parts of the Earth's mantle. The Pacific Plate is just one of the Earth's roughly 20 tectonic plates. Tectonic plates are constantly in motion and are responsible for volcanoes and events like earthquakes. -

Young Tracks of Hotspots and Current Plate Velocities

Geophys. J. Int. (2002) 150, 321–361 Young tracks of hotspots and current plate velocities Alice E. Gripp1,∗ and Richard G. Gordon2 1Department of Geological Sciences, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97401, USA 2Department of Earth Science MS-126, Rice University, Houston, TX 77005, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Accepted 2001 October 5. Received 2001 October 5; in original form 2000 December 20 SUMMARY Plate motions relative to the hotspots over the past 4 to 7 Myr are investigated with a goal of determining the shortest time interval over which reliable volcanic propagation rates and segment trends can be estimated. The rate and trend uncertainties are objectively determined from the dispersion of volcano age and of volcano location and are used to test the mutual consistency of the trends and rates. Ten hotspot data sets are constructed from overlapping time intervals with various durations and starting times. Our preferred hotspot data set, HS3, consists of two volcanic propagation rates and eleven segment trends from four plates. It averages plate motion over the past ≈5.8 Myr, which is almost twice the length of time (3.2 Myr) over which the NUVEL-1A global set of relative plate angular velocities is estimated. HS3-NUVEL1A, our preferred set of angular velocities of 15 plates relative to the hotspots, was constructed from the HS3 data set while constraining the relative plate angular velocities to consistency with NUVEL-1A. No hotspots are in significant relative motion, but the 95 per cent confidence limit on motion is typically ±20 to ±40 km Myr−1 and ranges up to ±145 km Myr−1.