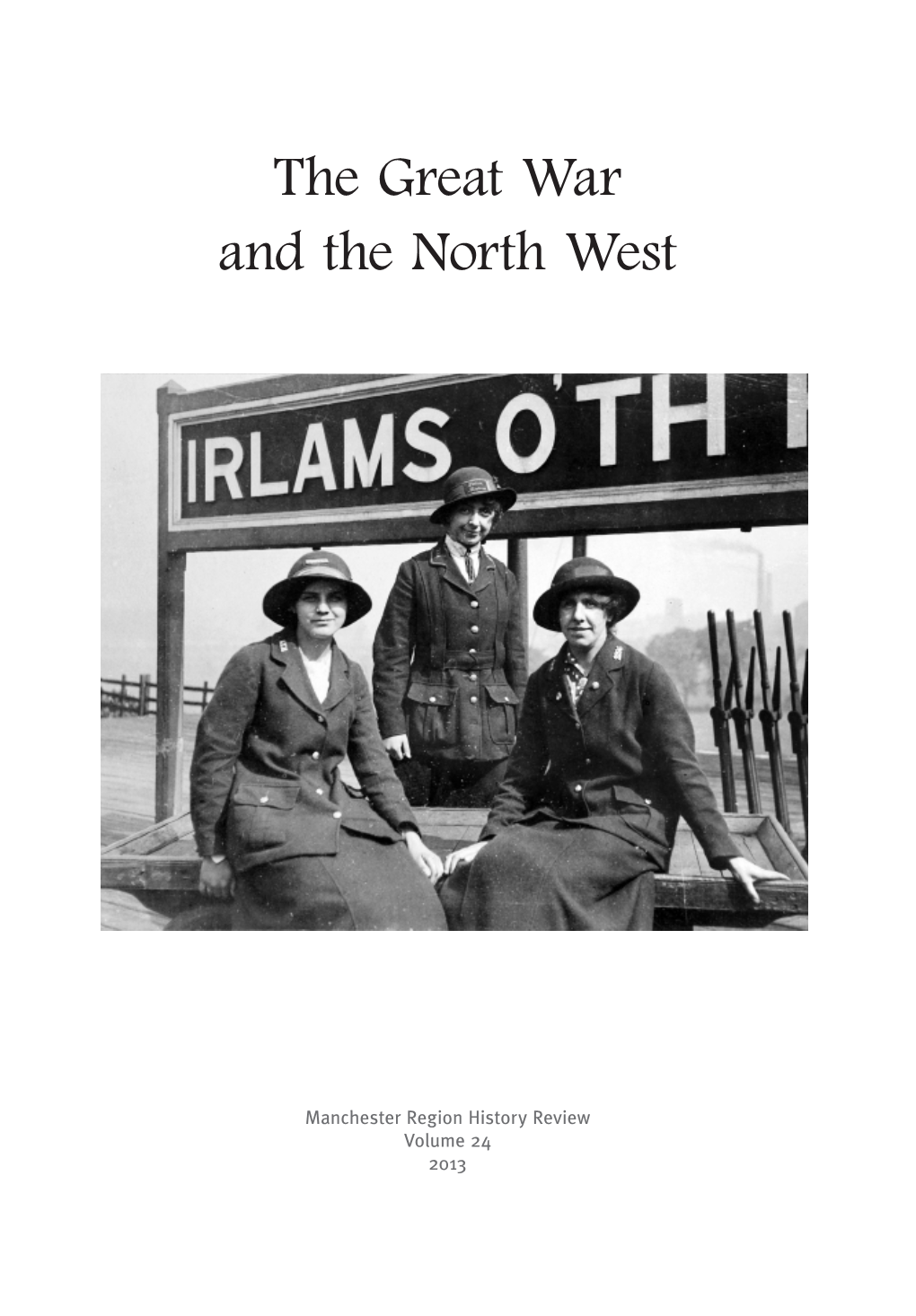

The Great War and the North West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glasgow Women's Library

SCOTTISH ARCHIVES 2016 Volume 22 © The Scottish Records Association Around the Archives Glasgow Women’s Library Nicola Maksymuik In the 25 years since its inception, Glasgow Women’s Library (GWL) has faced many challenges, including four changes of location, growing from a completely unfunded organisation run solely by volunteers to what it has become today – a well-respected, award-winning institution with unique archive, library and museum collections dedicated to women’s history. GWL is the only Accredited Museum of women’s history in the UK and in 2015 was awarded ‘Recognised Collection of National Significance’ status by Museums Galleries Scotland. As well as the archive and artefact collections that have grown over its 25- year history, the library also runs an innovative seasonal programme of public events and learning opportunities. Among its Core Projects there is also an Adult Literacy and Numeracy project; a Black and Minority Ethnic Women’s project; and a National Lifelong Learning project that delivers events and resources across Scotland. All of the library’s projects and programmes utilise the archive and museum collections in their work, and the collections inform and underpin almost everything that the library does. The library developed from an arts organisation called Women In Profile (WIP), which was established in 1987 with the aim of ensuring that women were represented when Glasgow became the European City of Culture in 1990. WIP consisted of artists, activists, academics and students, including the library’s co-founder and current Creative Development Manager, Dr Adele Patrick. The group ran projects, events, workshops and exhibitions before and during 1990. -

Chesterfield Wfa

CHESTERFIELD WFA Newsletter and Magazine issue 43 Co-Patrons -Sir Hew Strachan & Prof. Peter Welcome to Issue 43 - the July 2019 Simkins Newsletter and Magazine of Chesterfield President - Professor Gary WFA. Sheffield MA PhD FRHistS FRSA nd Our next meeting is on Tuesday evening, 2 July Vice-Presidents when our speaker will be the eminent historian Prof. John Bourne who is going to talk about `JRR Andre Colliot Tolkein and the 11th Lancashire Fusiliers on the Professor John Bourne BA PhD Somme` FRHistS The Burgomaster of Ypres The Mayor of Albert Lt-Col Graham Parker OBE Christopher Pugsley FRHistS Lord Richard Dannat GCB CBE MC DL Roger Lee PhD jssc Dr Jack Sheldon Branch contacts Tolkien in 1916, wearing his British Army uniform Tony Bolton (Chairman) anthony.bolton3@btinternet The Branch meets at the Labour Club, Unity House, Saltergate, .com Chesterfield S40 1NF on the first Tuesday of each month. There Mark Macartney (Deputy Chairman) is plenty of parking available on site and in the adjacent road. [email protected] Access to the car park is in Tennyson Road, however, which is Jane Lovatt (Treasurer) one way and cannot be accessed directly from Saltergate. Grant Cullen (Secretary) [email protected] Facebook Grant Cullen – Branch Secretary http://www.facebook.com/g roups/157662657604082/ http://www.wfachesterfield.com/ Western Front Association Chesterfield Branch – Meetings 2019 Meetings start at 7.30pm and take place at the Labour Club, Unity House, Saltergate, Chesterfield S40 1NF January 8th Jan.8th Branch AGM followed by a talk by Tony Bolton (Branch Chairman) on the key events of the first year after the Armistice. -

Public Statement Proposals for the Relocation of Manchester Cenotaph

Public statement Proposals for the relocation of Manchester Cenotaph and associated memorials Date: 10 September 2012 Status: Immediate release Starts War Memorials Trust has provided comments on the planning applications relating to the proposed relocation of the Manchester Cenotaph. Whilst the Trust agrees that the memorial is in need of some conservation and repair we are, at present, objecting to the proposal for the relocation of this important Grade II* Lutyens memorial and the later associated plaques. War Memorials Trust does not have a blanket opposition to relocation. If evidence demonstrating a need, and all relevant research and investigations has been done, then we accept it is sometimes necessary. All of our comments on this proposal, summarised below, are based on the information currently made publicly accessible through the planning system. We do not feel all appropriate investigations have been shown to be undertaken. However, we will be happy to comment further should additional information become available. War Memorials Trust has been involved in some meetings with Manchester City Council and Stephen Levrant: Heritage Architecture Ltd. regarding these proposals. At these meetings the Trust has raised a number of issues and reservations over the proposals. These include the loss of the group value between the Cenotaph and St Peters cross as well as the site more widely. Lutyens originally designed the memorial for this specific site and expressed a wish for the cross to remain in its location. War Memorials Trust only recommends relocation where a memorial is no longer publicly accessible or is at risk. This is due to the impact that relocation can have upon the longevity and structural integrity of the memorial. -

03Cii Appx a Salford Crescent Development Framework.Pdf

October 2020 THE CRESCENT SALFORD Draft Development Framework October 2020 1 Fire Station Square and A6 Crescent Cross-Section Visual Draft Crescent Development Framework October 2020 Contents 01 Introduction 8 Partners 02 Salford’s Time 24 03 The Vision 40 04 The Crescent: Contextual Analysis 52 05 Development Framework Area: Development Principles 76 06 Character Areas: Development Principles 134 07 Illustrative Masterplan 178 08 Delivering The Vision: Implementation & Phasing 182 Project Team APPENDICES Appendix A Planning Policy Appendix B Regeneration Context Appendix C Strategic Options 4 5 Draft Crescent Development Framework October 2020 Salford Crescent Visual - Aerial 6 7 Draft Crescent Development Framework October 2020 01. Introduction 8 9 Draft Crescent Development Framework October 2020 01. Introduction In recent years, Salford has seen a substantial and contributes significantly to Salford’s economy, The next 20 years are going to be very amount of investment in new homes, businesses, but is currently divided by natural and man-made infrastructure and the public realm. The delivery infrastructure including the River Irwell, railway line important for Salford; substantial progress has of major projects such as MediaCityUK, Salford and the A6/Crescent. This has led to parts of the been made in securing the city’s regeneration Central, Greengate, Port Salford and the AJ Bell Framework Area being left vacant or under-utilised. Stadium, and the revitalisation of road and riverside The expansion of the City Centre provides a unique with the city attracting continued investment corridors, has transformed large areas of Salford opportunity to build on the areas existing assets and had a significant impact on the city’s economy including strong transport connections, heritage from all over the world. -

The Female Art of War: to What Extent Did the Female Artists of the First World War Con- Tribute to a Change in the Position of Women in Society

University of Bristol Department of History of Art Best undergraduate dissertations of 2015 Grace Devlin The Female Art of War: To what extent did the female artists of the First World War con- tribute to a change in the position of women in society The Department of History of Art at the University of Bristol is commit- ted to the advancement of historical knowledge and understanding, and to research of the highest order. We believe that our undergraduates are part of that endeavour. For several years, the Department has published the best of the annual dis- sertations produced by the final year undergraduates in recognition of the excellent research work being undertaken by our students. This was one of the best of this year’s final year undergraduate disserta- tions. Please note: this dissertation is published in the state it was submitted for examination. Thus the author has not been able to correct errors and/or departures from departmental guidelines for the presentation of dissertations (e.g. in the formatting of its footnotes and bibliography). © The author, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means without the prior permission in writing of the author, or as expressly permitted by law. All citations of this work must be properly acknowledged. Candidate Number 53468 THE FEMALE ART OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR 1914-1918 To what extent did the female artists of the First World War contribute to a change in the position of women in society? Dissertation submitted for the Degree of B.A. -

Towpaths, Tracks and Tunnels

Tameside Countryside Service Coppicing Discover Coppicing is a traditional method of woodland management which Tameside’s takes advantage of the fact that many trees make new growth from Biodiversity is the variety of all life. It Countryside the stump or roots if cut down. In a includes plants, animals and the complex coppiced wood, young tree stems ecosytems of which they are part. Not are repeatedly cut down to near only do they enrich our everyday lives, ground level. In subsequent they produce the necessary ingredients for all life to exist. TOWPATHS,TRACKS growth years, many new shoots will emerge and after a number of Linking woodlands along the valley, the years the coppiced tree, or stool, is river and canal provide a wonderful AND TUNNELS ready to be harvested, and the wildlife habitat. cycle begins again. (The noun As you wander along the trail look out Mossley, Scout Tunnel and Staley Way "coppice" means a growth of small for Kingfisher and Heron. trees or a forest coming from The charismatic shoots or suckers.) Water Vole can still be found along some of the a recently coppiced borough's Alder stool. canals and brooks. Have you seen any wildlife? Please send your records to www.gmwildlife.org.uk Start: Mossley Railway Station, Manchester Road, Mossley OL5 0AB The same Alder stool after one year’s re-growth. Typically a coppiced woodland is STAMFORD ROAD harvested in sections or coups on a Mossley Station rotation. Coppicing has the effect of providing a rich variety of habitats, as the woodland always MANCHESTER ROAD has a range of different-aged coppice growing in it, which is Tameside Countryside Service beneficial for biodiversity. -

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 1

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 1 CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. CHAPTER X. CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. CHAPTER X. Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy The Project Gutenberg EBook of Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 2 License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy Author: George Biddell Airy Release Date: January 9, 2004 [EBook #10655] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SIR GEORGE AIRY *** Produced by Joseph Myers and PG Distributed Proofreaders AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF SIR GEORGE BIDDELL AIRY, K.C.B., M.A., LL.D., D.C.L., F.R.S., F.R.A.S., HONORARY FELLOW OF TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE, ASTRONOMER ROYAL FROM 1836 TO 1881. EDITED BY WILFRID AIRY, B.A., M.Inst.C.E. 1896 PREFACE. The life of Airy was essentially that of a hard-working, business man, and differed from that of other hard-working people only in the quality and variety of his work. It was not an exciting life, but it was full of interest, and his work brought him into close relations with many scientific men, and with many men high in the State. -

Gallipoli Campaign

tHe GaLlIpOlI CaMpAiGn The Gallipoli Campaign was an attack on the Gallipoli peninsula during World War I, between 25 April 1915 and 9 January 1916. The Gallipoli peninsula was an important tactical position during World War I. The British War Council suggested that Germany could be defeated by attacks on her allies, Austria, Hungary and Turkey. The Allied forces of the British Empire (including Australia and New Zealand) aimed to force a passage through the Dardanelles Strait and capture the Turkish capital, Constantinople. At dawn on 25 April 1915, Anzac assault troops landed north of Gaba Tepe, at what became known as Anzac Cove, while the British forces landed at Cape Helles on the Gallipoli Peninsula. The campaign was a brave but costly failure. By December 1915 plans were drawn up to evacuate the entire force from Gallipoli. On 19 and 20 December, the evacuation of over 142,000 men from Anzac Cove commenced and was completed three weeks later with minimal casualties. In total, the whole Gallipoli campaign caused 26,111 Australian casualties, including 8,141 deaths. Since 1916 the anniversary of the landings on 25 April has been commemorated as Anzac Day, becoming one of the most important national celebrations in Australia and New Zealand. tHe GaLlIpOlI CaMpAiGn The Gallipoli Campaign was an attack on the Gallipoli peninsula during World War I, between 25 April 1915 and 9 January 1916. The Gallipoli peninsula was an important tactical position during World War I. The British War Council suggested that Germany could be defeated by attacks on her allies, Austria, Hungary and Turkey. -

Issues and Options Topic Papers

Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council Local Development Framework Joint Core Strategy and Development Management Policies Development Plan Document Issues and Options Topic Papers February 2012 Strategic Planning Tameside MBC Room 5.16, Council Offices Wellington Road Ashton-under-Lyne OL6 6DL Tel: 0161 342 3346 Email: [email protected] For a summary of this document in Gujurati, Bengali or Urdu please contact 0161 342 8355 It can also be provided in large print or audio formats Local Development Framework – Core Strategy Issues and Options Discussion Paper Topic Paper 1 – Housing 1.00 Background • Planning Policy Statement 3: Housing (PPS3) • Regional Spatial Strategy North West • Planning for Growth, March 2011 • Manchester Independent Economic Review (MIER) • Tameside Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment (SHLAA) • Tameside Strategic Housing Market Assessment 2008 (SHMA) • Tameside Unitary Development Plan 2004 • Tameside Housing Strategy 2010-2016 • Tameside Sustainable Community Strategy 2009-2019 • Gypsy and Traveller Accommodation Assessment • Tameside Residential Design Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) 1.01 The Tameside Housing Strategy 2010-2016 is underpinned by a range of studies and evidence based reports that have been produced to respond to housing need at a local level as well as reflecting the broader national and regional housing agenda. 2.00 National Policy 2.01 At the national level Planning Policy Statement 3: Housing (PPS3) sets out the planning policy framework for delivering the Government's housing objectives setting out policies, procedures and standards which Local Planning Authorities must adhere to and use to guide local policy and decisions. 2.02 The principle aim of PPS3 is to increase housing delivery through a more responsive approach to local land supply, supporting the Government’s goal to ensure that everyone has the opportunity of living in decent home, which they can afford, in a community where they want to live. -

The LSRA Collection

i Return to Contents TheThe LSRALSRA CollectionCollection A Collection of Pipe Tunes By Joe Massey and Chris Eyre dedicated to the Liverpool Scottish and their Regimental Association i ii Return to Contents The tunes in this book are drawn mainly from the Airs & Graces Books 1 and 2 that Joe and I produced around 2002- 2005 with the addition of several more tunes I have written since, plus a lot more background information and illustrations. Some of the tunes have been revised/updated, had some minor mistakes corrected, been improved slightly or had harmony added. Joe’s tunes are already in the public domain. I’m making all mine available too. All I ask is that if you use any of the tunes you acknowledge who wrote them. I’m not planning to publish this book in hardback. It is designed as an e-book which has several advantages over a conventional hard-back. In this publication you can zoom in on any of the high resolution pictures, click on any title on the Contents page to go straight to the tune, click “Return to Contents” to go back to the tune list and even listen to many of the tunes by clicking on the link below to my webpage. http://www.eyrewaves.co.uk/pipingpages/ Airs_and_Graces.asp If you prefer a hard copy you are welcome to print out any tune or the entire book. Chris Eyre ii iii Return to Contents CONTENTS (Click on any tune to go to it) PAGE 1. Colonel and Mrs Anne Paterson 2. -

Annex One: the Lancashire and Blackpool Tourist Board Destination Management Plan Local Authority Activity

Annex One: The Lancashire and Blackpool Tourist Board Destination Management Plan Local Authority Activity Local Authority Activity Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council Proposed Tourism Support Activity www.blackburn.gov.uk; www.visitblackburn.co.uk Blackburn Town Centre Strategy (Inc Leisure and Evening Economy 2010-2115 Strategy) 2008 – 15 Blackburn town Centre Marketing Strategy 2004 -2010 Darwen Town Centre Strategy 2010-2011 Blackburn and Darwen Town Centre Business Plans LSP LAA and Corporate Performance Agreement Developing Vision for 2030 for Blackburn with Darwen Other relevant local strategies/frameworks Cathedral Quarter SPD Great goals – Local Enterprise Growth Initiative Elevate – Housing Regeneration Strategy Pennine Lancashire Transformational Agenda Lancashire Economic Strategy Regional Economic Strategy Pennine Lancs Integrated Economic Strategy Pennine Lancs MAA Continuing Provision Forward Programme Visitor Information Providing 1 fully staffed Visitor Centre, 1information center in Darwen and 2 Integrate LBTB Marketing Strategy into the Visitor Centre Offer, countryside Visitor Centres. promoting themes, events and initiatives in the ‘shop window’, and Continue to equality proof the service to ensure widest accessibility supporting with the retail strategy Continue exhibitions programme at Blackburn Visitor Centre to support visitor Improve communications with VE businesses to promote opportunities economy and town centre masterplan scheme. and initiatives. Partner in LBTB Taste Lancashire promotions. Develop a 3 year business plan for the development, delivery and Produce annual visitor guide. sustainability of visitor services. Maximize opportunities in partner publications and websites. Continue to look at opportunities for wider visitor information, eg Turton Support visit websites and regularly update BwD product and services through Tower, Darwen, Museum etc visitlancashire.com Relaunch improved visitblackburn website after merging with Compile annual and monthly Borough events diary. -

1 Introduction

Cambridge University Press 0521848008 - Citizen Soldiers: The Liverpool Territorials in the First World War Helen B. McCartney Excerpt More information 1 Introduction The First World War drew ordinary British men into an army that by 1918 numbered over 5 million soldiers.1 Some had volunteered to serve; others had been less willing and were conscripted later in the war. Most had little contact with the military in pre-war days, and before 1914 few would have contemplated participating in war. These men were first and foremost civilians, and this book examines their experience from their initial decision to enlist, through trench warfare on the Western Front, to death, discharge or demobilization at the end of the war. It is concerned with the soldier’s relationship both with the army and with home, and examines the extent to which these citizen soldiers maintained their civilian values, attitudes, skills and traditions and applied them to the task of soldiering in the period of the First World War. The popular image of the British soldier in the First World War is that of a passive victim of the war in general and the military system in particular. On joining the army a soldier supposedly ceased to act as an individual and lost his ability to shape his world. It is an image that has been reinforced by two historiographical traditions and is largely derived from a narrow view of the British soldier presented by the self-selecting literary veterans who wrote the disillusionment literature of the late 1920s and 1930s.2 For some historians, the characteristics of the British ‘Tommy’ have become synonymous with the qualities of the regular pre-war private soldier.