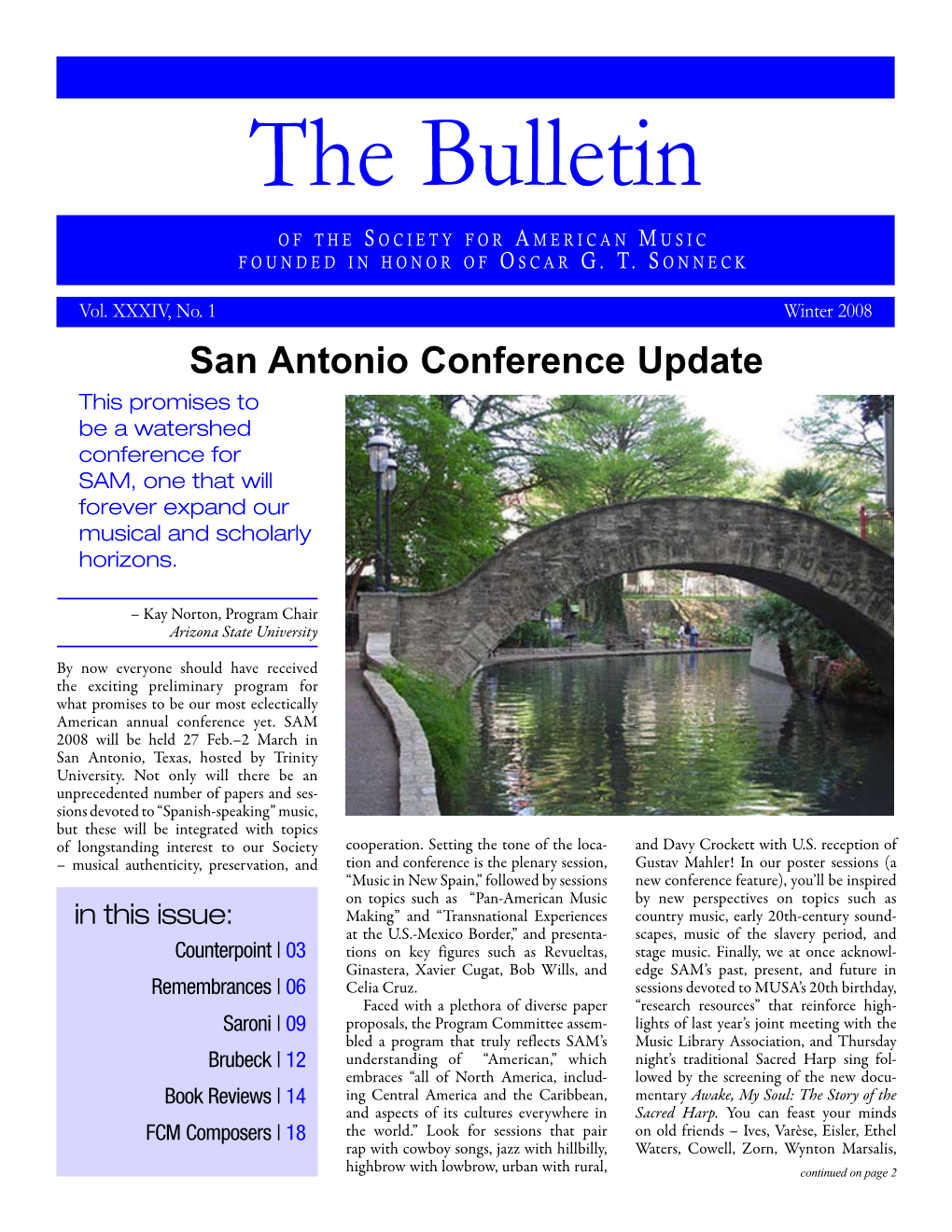

The Bulletin O F T H E So C I E T Y F O R Am E R I C a N Mu S I C F O U N D E D in H O N O R O F Os C a R G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musical Landmarks in New York

MUSICAL LANDMARKS IN NEW YORK By CESAR SAERCHINGER HE great war has stopped, or at least interrupted, the annual exodus of American music students and pilgrims to the shrines T of the muse. What years of agitation on the part of America- first boosters—agitation to keep our students at home and to earn recognition for our great cities as real centers of musical culture—have not succeeded in doing, this world catastrophe has brought about at a stroke, giving an extreme illustration of the proverb concerning the ill wind. Thus New York, for in- stance, has become a great musical center—one might even say the musical center of the world—for a majority of the world's greatest artists and teachers. Even a goodly proportion of its most eminent composers are gathered within its confines. Amer- ica as a whole has correspondingly advanced in rank among musical nations. Never before has native art received such serious attention. Our opera houses produce works by Americans as a matter of course; our concert artists find it popular to in- clude American compositions on their programs; our publishing houses publish new works by Americans as well as by foreigners who before the war would not have thought of choosing an Amer- ican publisher. In a word, America has taken the lead in mu- sical activity. What, then, is lacking? That we are going to retain this supremacy now that peace has come is not likely. But may we not look forward at least to taking our place beside the other great nations of the world, instead of relapsing into the status of a colony paying tribute to the mother country? Can not New York and Boston and Chicago become capitals in the empire of art instead of mere outposts? I am afraid that many of our students and musicians, for four years compelled to "make the best of it" in New York, are already looking eastward, preparing to set sail for Europe, in search of knowledge, inspiration and— atmosphere. -

1962 FMAC SS.Pdf

WIND DRUM The music of WIND DRUM is composed on a six-tone scale. In South India, this scale is called "hamsanandi," in North India, "marava." In North India, this scale would be played before sunset. The notes are C, D flat, E, F sharp, A, and B. PREFACE The mountain island of Hawaii becomes a symbol of an island universe in an endless ocean of nothingness, of space, of sleep. This is the night of Brahma. Time swings back and forth, time, the giant pendulum of the universe. As time swings forward all things waken out of endless slumber, all things grow, dance, and sing. Motion brings storm, whirlwind, tornado, devastation, destruction, and annihilation. All things fall into death. But with total despair comes sudden surprise. The super natural commands with infinite majesty. All storms, all motions cease. Only the celestial sounds of the Azura Heavens are heard. Time swings back, death becomes life, resurrection. All things are reborn, grow, dance, and sing. But the spirit of ocean slumber approaches and all things fall back again into sleep and emptiness, the state of endless nothingness symbolized by ocean. The night of Brahma returns. LIBRETTO I VI Stone, water, singing grass, Flute of Azura, Singing tree, singing mountain, Fill heaven with celestial sound! Praise ever-compassionate One. Death, become life! II VII Island of mist, Sun, melt, dissolve Awake from ocean Black-haired mountain storm, Of endless slumber. Life drum sing, III Stone drum ring! Snow mountain, VIII Dance on green hills. Trees singing of branches IV Sway winds, Three hills, Forest dance on hills, Dance on forest, Hills, green, dance on Winds, sway branches Mountain snow. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

ALAN HOVHANESS: Meditation on Orpheus the Japan Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra William Strickland, Conducting

ALAN HOVHANESS: Meditation on Orpheus The Japan Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra William Strickland, conducting ALAN HOVHANESS is one of those composers whose music seems to prove the inexhaustability of the ancient modes and of the seven tones of the diatonic scale. He has made for himself one of the most individual styles to be found in the work of any American composer, recognizable immediately for its exotic flavor, its masterly simplicity, and its constant air of discovering unexpected treasures at each turn of the road. Meditation on Orpheus, scored for full symphony orchestra, is typical of Hovhaness’ work in the delicate construction of its sonorities. A single, pianissimo tam-tam note, a tone from a solo horn, an evanescent pizzicato murmur from the violins (senza misura)—these ethereal elements tinge the sound of the middle and lower strings at the work’s beginning and evoke an ambience of mysterious dignity and sensuousness which continues and grows throughout the Meditation. At intervals, a strange rushing sound grows to a crescendo and subsides, interrupting the flow of smooth melody for a moment, and then allowing it to resume, generally with a subtle change of scene. The senza misura pizzicato which is heard at the opening would seem to be the germ from which this unusual passage has grown, for the “rushing” sound—dynamically intensified at each appearance—is produced by the combination of fast, metrically unmeasured figurations, usually played by the strings. The composer indicates not that these passages are to be played in 2/4, 3/4, etc. but that they are to last “about 20 seconds, ad lib.” The notes are to be “rapid but not together.” They produce a fascinating effect, and somehow give the impression that other worldly significances are hidden in the juxtaposition of flow and mystical interruption. -

April 1 & 3, 2021 Walt Disney Theater

April 1 & 3, 2021 Walt Disney Theater FAIRWINDS GROWS MY MONEY SO I CAN GROW MY BUSINESS. Get the freedom to go further. Insured by NCUA. OPERA-2646-02/092719 Opera Orlando’s Carmen On the MainStage at Dr. Phillips Center | April 2021 Dear friends, Carmen is finally here! Although many plans have changed over the course of the past year, we have always had our sights set on Carmen, not just because of its incredible music and compelling story but more because of the unique setting and concept of this production in particular - 1960s Haiti. So why transport Carmen and her friends from 1820s Seville to 1960s Haiti? Well, it all just seemed to make sense, for Orando, that is. We have a vibrant and growing Haitian-American community in Central Florida, and Creole is actually the third most commonly spoken language in the state of Florida. Given that Creole derives from French, and given the African- Carribean influences already present in Carmen, setting Carmen in Haiti was a natural fit and a great way for us to celebrate Haitian culture and influence in our own community. We were excited to partner with the Greater Haitian American Chamber of Commerce for this production and connect with Haitian-American artists, choreographers, and academics. Since Carmen is a tale of survival against all odds, we wanted to find a particularly tumultuous time in Haiti’s history to make things extra difficult for our heroine, and setting the work in the 1960s under the despotic rule of Francois Duvalier (aka Papa Doc) certainly raised the stakes. -

La Recepción Temprana De Wagner En Estados Unidos: Wagner En La Kleindeutschland De Nueva York, 1854-1874

Resonancias vol. 19, n°35, junio-noviembre 2014, pp. 11-24 La recepción temprana de Wagner en Estados Unidos: Wagner en la Kleindeutschland de Nueva York, 1854-1874 F. Javier Albo Georgia State University, Atlanta, USA. [email protected] Resumen Este trabajo se centra en la recepción de la música de Richard Wagner, limitado a un marco geográfico específico, el de la ciudad de Nueva York –en concreto el distrito alemán de la ciudad, conocido como Kleindeutschland– y temporal, el comprendido entre la primera ejecución documentada de una obra de Wagner en la ciudad, en 1854, y la definitiva entronización del compositor como legítimo representante de la tradición musical alemana a partir del estreno de Lohengrin en la Academy of Music, en 1874. Se destaca la labor de promoción a cargo de los emigrantes alemanes, en su papel de mediadores, en los años 50 y 60 del siglo XIX, una labor fundamental ya que gracias a ella germinó la semilla del culto a Wagner que eclosionaría durante la Gilded Age, la “Edad dorada” del desarrollo económico y artístico finisecular, que afectó a todo el país pero de manera especial a Nueva York. Asimismo, se incluye una aproximación a la recepción en la crítica periodística neoyorquina durante el periodo en cuestión. Palabras clave: Wagner; Recepción temprana en Nueva York; Músicos alemanes y emigración, 1850-1875; Crítica periodística. Abstract This study discusses the early reception of Richard Wagner’s music in New York, starting with the first documented performance of a work by Wagner in the city, in 1854, and the momentous production of Lohengrin at the Academy of Music, in 1874. -

A Literary Journey to Rome

A Literary Journey to Rome A Literary Journey to Rome: From the Sweet Life to the Great Beauty By Christina Höfferer A Literary Journey to Rome: From the Sweet Life to the Great Beauty By Christina Höfferer This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Christina Höfferer All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7328-4 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7328-4 CONTENTS When the Signora Bachmann Came: A Roman Reportage ......................... 1 Street Art Feminism: Alice Pasquini Spray Paints the Walls of Rome ....... 7 Eataly: The Temple of Slow-food Close to the Pyramide ......................... 11 24 Hours at Ponte Milvio: The Lovers’ Bridge ......................................... 15 The English in Rome: The Keats-Shelley House at the Spanish Steps ...... 21 An Espresso with the Senator: High-level Politics at Caffè Sant'Eustachio ........................................................................................... 25 Ferragosto: When the Romans Leave Rome ............................................. 29 Myths and Legends, Truth and Fiction: How Secret is the Vatican Archive? ................................................................................................... -

Here Are a Number of Recognizable Singers Who Are Noted As Prominent Contributors to the Songbook Genre

Music Take- Home Packet Inside About the Songbook Song Facts & Lyrics Music & Movement Additional Viewing YouTube playlist https://bit.ly/AllegraSongbookSongs This packet was created by Board-Certified Music Therapist, Allegra Hein (MT-BC) who consults with the Perfect Harmony program. About the Songbook The “Great American Songbook” is the canon of the most important and influential American popular songs and jazz standards from the early 20th century that have stood the test of time in their life and legacy. Often referred to as "American Standards", the songs published during the Golden Age of this genre include those popular and enduring tunes from the 1920s to the 1950s that were created for Broadway theatre, musical theatre, and Hollywood musical film. The times in which much of this music was written were tumultuous ones for a rapidly growing and changing America. The music of the Great American Songbook offered hope of better days during the Great Depression, built morale during two world wars, helped build social bridges within our culture, and whistled beside us during unprecedented economic growth. About the Songbook We defended our country, raised families, and built a nation while singing these songs. There are a number of recognizable singers who are noted as prominent contributors to the Songbook genre. Ella Fitzgerald, Fred Astaire, Rosemary Clooney, Nat King Cole, Sammy Davis Jr., Judy Garland, Billie Holiday, Lena Horne, Al Jolson, Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra, Mel Tormé, Margaret Whiting, and Andy Williams are widely recognized for their performances and recordings which defined the genre. This is by no means an exhaustive list; there are countless others who are widely recognized for their performances of music from the Great American Songbook. -

American Friends of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra to Honor Legendary Composer Stanley Silverman at Annual Gala in Beverly Hills

AMERICAN FRIENDS OF THE ISRAEL PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA TO HONOR LEGENDARY COMPOSER STANLEY SILVERMAN AT ANNUAL GALA IN BEVERLY HILLS Silverman will be honored at the organization’s Los Angeles gala on October 25, 2018, which will bring together entertainment, music and philanthropic notables for an evening celebrating the global impact of music LOS ANGELES, August 24, 2018 - Stanley Silverman will be honored by the American Friends of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra (AFIPO), on the occasion of his 80th birthday, at their upcoming Los Angeles gala, October 25, 2018 at the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts in Beverly Hills. The event will honor the life and work of the diverse Grammy and Tony nominated American composer, with a program inclusive of classical and popular music Silverman has composed for both theater and film, along with remarks by special guests. Actors Rob Morrow and Jane the Virgin star Jaime Camil will MC the event. Pianist Ory Shihor will perform alongside members of the Israel Philharmonic. Silverman joins other musical legends who have been honored by the AFIPO at their Los Angeles gala, including multi-Oscar winning composer Hans Zimmer in 2014, and conductor Zubin Mehta in 2017. “I am honored to be receiving this recognition from the AFIPO,” said Silverman, “As a passionate supporter of the organization, I am very much looking forward to the gala in October and hearing some of my important pieces played by these musicians of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra.” “From the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra’s founding, by some of the best musicians across Europe, the roots of the orchestra have always been about moving the world through music. -

Fiscal Year 2017 Appropriations Request

National Endowment for the Arts Appropriations Request For Fiscal Year 2017 Submitted to the Congress February 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Appropriations Request for Fiscal Year 2017 Submitted to the Congress February 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Overview ......................................................................... 1 II. Creation of Art .............................................................. 21 III. Engaging the Public with Art ........................................ 33 IV. Promoting Public Knowledge and Understanding ........ 83 V. Program Support ......................................................... 107 VI. Salaries and Expenses ................................................. 115 www.arts.gov BLANK PAGE National Endowment for the Arts – Appropriations Request for FY 2017 OVERVIEW The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) is America’s chief funder and supporter of the arts. As an independent Federal agency, the NEA celebrates the arts as a national priority, critical to America’s future. More than anything, the arts provide a space for us to create and express. Through grants given to thousands of non-profits each year, the NEA helps people in communities across America experience the arts and exercise their creativity. From visual arts to digital arts, opera to jazz, film to literature, theater to dance, to folk and traditional arts, healing arts to arts education, the NEA supports a broad range of America’s artistic expression. Throughout the last 50 years, the NEA has made a significant contribution to art and culture in America. The NEA has made over 147,000 grants totaling more than $5 billion dollars, leveraging up to ten times that amount through private philanthropies and local municipalities. The NEA further extends its work through partnerships with state arts agencies, regional arts organizations, local leaders, and other Federal agencies, reaching rural, suburban, and metropolitan areas in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, special jurisdictions, and military installations. -

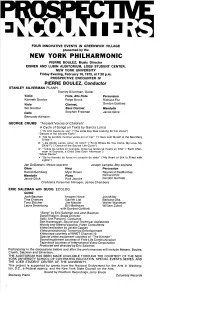

Prospective Encounters

FOUR INNOVATIVE EVENTS IN GREENWICH VILLAGE presented by the NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC PIERRE BOULEZ, Music Director EISNER AND LUBIN AUDITORIUM, LOEB STUDENT CENTER, NEW YORK UNIVERSITY Friday Evening, February 18, 1972, at 7:30 p.m. PROSPECTIVE ENCOUNTER IV PIERRE BOULEZ, Conductor STANLEY SILVERMAN PLANH Stanley Silverman, Guitar Violin Flute, Alto Flute Percussion Kenneth Gordon Paige Brook Richard Fitz Viola Clarinet, Gordon Gottlieb Sol Greitzer Bass Clarinet Mandolin Cello Stephen Freeman Jacob Glick Bernardo Altmann GEORGE CRUMB "Ancient Voices of Children" A Cycle of Songs on Texts by Garcia Lorca I "El niho busca su voz" ("The Little Boy Was Looking for his Voice") "Dances of the Ancient Earth" II "Me he perdido muchas veces por el mar" ("I Have Lost Myself in the Sea Many Times") III "6De d6nde vienes, amor, mi nino?" ("From Where Do You Come, My Love, My Child?") ("Dance of the Sacred Life-Cycle") IV "Todas ]as tardes en Granada, todas las tardes se muere un nino" ("Each After- noon in Granada, a Child Dies Each Afternoon") "Ghost Dance" V "Se ha Ilenado de luces mi coraz6n de seda" ("My Heart of Silk Is Filled with Lights") Jan DeGaetani, Mezzo-soprano Joseph Lampke, Boy soprano Oboe Harp Percussion Harold Gomberg Myor Rosen Raymond DesRoches Mandolin Piano Richard Fitz Jacob Glick PaulJacobs Gordon Gottlieb Orchestra Personnel Manager, James Chambers ERIC SALZMAN with QUOG ECOLOG QUOG Josh Bauman Imogen Howe Jon Miller Tina Chancey Garrett List Barbara Oka Tony Elitcher Jim Mandel Walter Wantman Laura Greenberg Bill Matthews -

November 13 – the Best of Broadway

November 13 – The Best of Broadway SOLOISTS: Bill Brassea Karen Babcock Brassea Rebecca Copley Maggie Spicer Perry Sook PROGRAM Broadway Tonight………………………………………………………………………………………………Arr. Bruce Chase People Will Say We’re in Love from Oklahoma……….…..Rodgers & Hammerstein/Robert Bennett Try to Remember from The Fantasticks…………………………………………………..Jack Elliot/Jack Schmidt Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man from Show Boat……………………………Oscar Hammerstein/Jerome Kern/ Robert Russell Bennett Gus: The Theatre Cat from Cats……………………………………….……..…Andrew Lloyd Webber/T.S. Eliot Selections from A Chorus Line…………………………………….……..Marvin Hamlisch/Arr. Robert Lowden Glitter and Be Gay from Candide…………………….………………………………………………Leonard Bernstein Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off from Shall We Dance…….…….……………………George & Ira Gershwin Impossible Dream from Man of La Mancha………………………………………….…Mitch Leigh/Joe Darion Mambo from Westside Story……………………………………………..…………………….…….Leonard Bernstein Somewhere from Westside Story……………………………………….…………………….…….Leonard Bernstein Intermission Seventy-Six Trombones from The Music Man………………………….……………………….Meredith Willson Before the Parade Passes By from Hello, Dolly!……………………………John Herman/Michael Stewart Vanilla Ice Cream from She Loves Me…………..…………....…………………….Sheldon Harnick/Jerry Bock Be a Clown from The Pirate..…………………………………..………………………………………………….Cole Porter Summer Time from Porgy & Bess………………………………………………………….………….George Gershwin Move On from Sunday in the Park with George………….……..Stephen Sondheim/Michael Starobin The Grass is Always Greener from Woman of the Year………….John Kander/Fred Ebb/Peter Stone Phantom of the Opera Overture……………………………………………………………….Andrew Lloyd Webber Music of the Night from Phantom of the Opera…….………………………………….Andrew Lloyd Webber Love Never Dies from Love Never Dies………………..…..……………………………….Andrew Lloyd Webber Over the Rainbow from The Wizard of Oz….……………………………………….Harold Arlen/E.Y. Harburg Arr. Mark Hayes REHEARSALS: Mon., Oct. 17 7 p.m.