A Case Study of Oxfam GB Response to Urban

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contesting Candidates NA-1 Peshawar-I

Form-V: List of Contesting Candidates NA-1 Peshawar-I Serial No Name of contestng candidate in Address of contesting candidate Symbol Urdu Alphbeticl order Allotted 1 Sahibzada PO Ashrafia Colony, Mohala Afghan Cow Colony, Peshawar Akram Khan 2 H # 3/2, Mohala Raza Shah Shaheed Road, Lantern Bilour House, Peshawar Alhaj Ghulam Ahmad Bilour 3 Shangar PO Bara, Tehsil Bara, Khyber Agency, Kite Presented at Moh. Gul Abad, Bazid Khel, PO Bashir Ahmad Afridi Badh Ber, Distt Peshawar 4 Shaheen Muslim Town, Peshawar Suitcase Pir Abdur Rehman 5 Karim Pura, H # 282-B/20, St 2, Sheikhabad 2, Chiragh Peshawar (Lamp) Jan Alam Khan Paracha 6 H # 1960, Mohala Usman Street Warsak Road, Book Peshawar Haji Shah Nawaz 7 Fazal Haq Baba Yakatoot, PO Chowk Yadgar, H Ladder !"#$%&'() # 1413, Peshawar Hazrat Muhammad alias Babo Maavia 8 Outside Lahore Gate PO Karim Pura, Peshawar BUS *!+,.-/01!234 Khalid Tanveer Rohela Advocate 9 Inside Yakatoot, PO Chowk Yadgar, H # 1371, Key 5 67'8 Peshawar Syed Muhammad Sibtain Taj Agha 10 H # 070, Mohala Afghan Colony, Peshawar Scale 9 Shabir Ahmad Khan 11 Chamkani, Gulbahar Colony 2, Peshawar Umbrella :;< Tariq Saeed 12 Rehman Housing Society, Warsak Road, Fist 8= Kababiyan, Peshawar Amir Syed Monday, April 22, 2013 6:00:18 PM Contesting candidates Page 1 of 176 13 Outside Lahori Gate, Gulbahar Road, H # 245, Tap >?@A= Mohala Sheikh Abad 1, Peshawar Aamir Shehzad Hashmi 14 2 Zaman Park Zaman, Lahore Bat B Imran Khan 15 Shadman Colony # 3, Panal House, PO Warsad Tiger CDE' Road, Peshawar Muhammad Afzal Khan Panyala 16 House # 70/B, Street 2,Gulbahar#1,PO Arrow FGH!I' Gulbahar, Peshawar Muhammad Zulfiqar Afghani 17 Inside Asiya Gate, Moh. -

Mansehra Food Security Project in Pakistan

External evaluation of the Mansehra Food Security Project in Pakistan Evaluation Mission 19 Jan to 7 Feb 6 2012 Final Report: March, 2012 Authors: Paigham Shah, Crop/Agricultural Specialist, Team Leader Khalid Nawab Extension Expert Hafsa Naheed, Post graduate student Sana Abid, Post graduate student 1 Acknowledgements The evaluation team would like to thank the CWW staff at Islamabad and Abbottabad for their extraordinary welcome, cooperation and support. The team appreciates the useful discussions with CWW staff for the evaluation of the MFSP. The team is also thankful the staff of the two partner organizations, Haashar Associations and Rural Development Project, for their full cooperation in field visits and useful discussion. We, the members of evaluation team, are also thankful to the local communities including members of village organizations, beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries; and government line department officials who spared their time to meet the members of the evaluation team and had useful discussion with the members of the team; we appreciate the sharing of their opinions, experiences, and expertise with the team members. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the independent evaluation team and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Concern Worldwide Pakistan, the implementing partners, CWW project staff, Government of Pakistan, Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. A portion of water channel rehabilitated A view of the forest nursery established by RDP near Alari village, UC Shoal by -

Mardan (Posts-1) Scoring Key: Grade Wise Marks 1St Div: 2Nd Div: 3Rd Div: Age 25-35 Years 1

At least 2nd Division Master in Social Sciences (Social Work/ Sociology will be preferred) District: Mardan (Posts-1) Scoring Key: Grade wise marks 1st Div: 2nd Div: 3rd Div: Age 25-35 Years 1. (a) Basic qualification Marks 60 S.S.C 15 11 9 Date of Advertisement:- 22-08-2020 2. Higher Qualification Marks (One Step above-7 Marks, Two Stage Above-10 Marks) 10 F.A/FSc 15 11 9 SOCIAL CASE WORKER (BPS-16) 3. Experience Certificate 15 BA/BSc 15 11 9 4. Interviews Marks 8 MA/MSc 15 11 9 5. Professional Training Marks 7 Total;- 60 44 36 Total;- 100 LIST OF CANDIDATES FOR APPOINTMENT TO THE POST OF SOCIAL CASE WORKER BPS-16 BASIC QUALIFICATION Higher Qual: SSC FA/FSC BA/BSc M.A/ MS.c S. # on Name/Father's Name and address Total S. # Appli: Remarks Domicile Malrks= 7 Total Marks Marks Marks Marks Marks Date of Birth Qualification Division Division Division Division Marks P.HD Marks M.Phil Marks of Experience Professional/Training One Stage Above 7 Two Two Stage Above 10 Interview Marks 8 Marks Year of Experience 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Mr. Farhan Raza S/O Abid Raza, Koz Kaly Madyan, P.O Madyan, Tehsil and District Swat, 0314- Mphil Agriculture Rual 71 3/2/1992 Swat 1st 15 1st 15 1st 15 1st 15 10 70 70 9818407 Sociology Mr. Muhammad Asif Khan S/O Muhammad Naeem Khan, Rahat Abad Colony, Bannu Road P.O PHD Business 494 16-04-1990 Lakki Marwat 1st 15 1st 15 1st 15 1st 15 10 70 70 Sheikh Yousaf District D.I.Khan. -

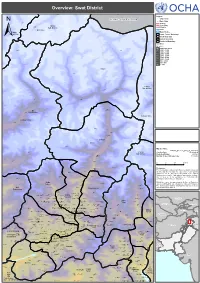

Swat District !

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Overview: Swat District ! ! ! ! SerkiSerki Chikard Legend ! J A M M U A N D K A S H M I R Citiy / Town ! Main Cities Lohigal Ghari ! Tertiary Secondary Goki Goki Mastuj Shahi!Shahi Sub-division Primary CHITRAL River Chitral Water Bodies Sub-division Union Council Boundary ± Tehsil Boundary District Boundary ! Provincial Boundary Elevation ! In meters ! ! 5,000 and above Paspat !Paspat Kalam 4,000 - 5,000 3,000 - 4,000 ! ! 2,500 - 3,000 ! 2,000 - 2,500 1,500 - 2,000 1,000 - 1,500 800 - 1,000 600 - 800 0 - 600 Kalam ! ! Utror ! ! Dassu Kalam Ushu Sub-division ! Usho ! Kalam Tal ! Utrot!Utrot ! Lamutai Lamutai ! Peshmal!Harianai Dir HarianaiPashmal Kalkot ! ! Sub-division ! KOHISTAN ! ! UPPER DIR ! Biar!Biar ! Balakot Mankial ! Chodgram !Chodgram ! ! Bahrain Mankyal ! ! ! SWAT ! Bahrain ! ! Map Doc Name: PAK078_Overview_Swat_a0_14012010 Jabai ! Pattan Creation Date: 14 Jan 2010 ! ! Sub-division Projection/Datum: Baranial WGS84 !Bahrain BahrainBarania Nominal Scale at A0 paper size: 1:135,000 Ushiri ! Ushiri Madyan ! 0 5 10 15 kms ! ! ! Beshigram Churrai Churarai! Disclaimers: Charri The designations employed and the presentation of material Tirat Sakhra on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Beha ! Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, Bar Thana Darmai Fatehpur city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the Kwana !Kwana delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Kalakot Matta ! Dotted line represents a!pproximately the Line of Control in Miandam Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. Sebujni Patai Olandar Paiti! Olandai! The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been Gowalairaj Asharay ! Wari Bilkanai agreed upon by the parties. -

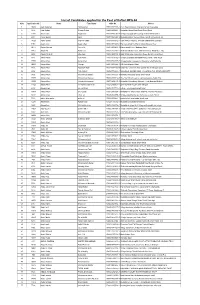

List of Candidates Applied for the Post of Daftari BPS-04 S.No Application No Name Fater Name CNIC No

List of Candidates applied for the Post of Daftari BPS-04 S.No Application No Name Fater Name CNIC No. Addrss 1 15494 Aadil badshah Gul badshah 17101-7677906-1 moh: Dagi mukaram khan p/o tarnab charsadda 2 3214 Aadil Sultan Shuaib Sultan 15602-0930493-7 Mohallah Nasar Khail Saidu Sharif Swat 3 11940 Aamer Jan Sajid khan 17101-7001946-7 Village and post office prang mohalla baba khel te 4 4911 Aamir Sohail Iqbal 15607-0343286-9 Mohallah Chinar Colony,Village and P /O Amankot, M 5 18620 Aamir Sohail Wajeeh Uddin 15607-0365372-7 Swat Plastic Industry, Mohalla Sadbarabad, Balogra 6 1950 Aaqib ullah Aaqib Ullah 15602-9778439-1 Rahman Abad P.o Rahim Abad Mingora Swat 7 10771 Abbas Ahmad Amir Zeb 15607-0339468-9 Rahimabad Tehsel Babozai Swat 8 17711 Abbas Ali Akbar Gul 17301-2133451-1 Shaheen Muslim town, Mohallah Nazer Abad No 2, Hou 9 2403 Abbas Ali Shah Hamayun 15602-9235154-5 Sabir Shah Law Associates Room No.S8,9, 2nd Floor, 10 4185 Abbas Khan Ajab Khan 16101-1106142-7 Village Bughdada Mohallah Mianz Kandi Tehsil & Dis 11 17753 Abbas khan Akbar khan 15302-7569697-7 Village kandaro payee p/o timergara tehsil balamba 12 10963 Abbas Khan Alamgir 15607-0383252-3 PO Box Odigram Swat 13 7518 Abbas Khan Badshah Zada 15602-8847450-9 Falak Naz Jewellers Main Sarafa Bazar Mingora Swat 14 2602 Abbas Khan GUL MALIK 15602-7712428-1 MOHALLA: SAYED ABAD, VILLAGE & P/O: MANGLOR,DISTT: 15 3802 Abbas Khan Muhammad Sardar 15607-0360756-9 Mohalla Afsarabad Saidu Sharif Swat 16 17173 Abbas khan Muhammad Sarwar 15602-0357410-5 The City School near to wali swat -

J. Bio. & Env. Sci. 2019

J. Bio. & Env. Sci. 2019 Journal of Biodiversity and Environmental Sciences (JBES) ISSN: 2220-6663 (Print) 2222-3045 (Online) Vol. 14, No. 6, p. 103-113, 2019 http://www.innspub.net RESEARCH PAPER OPEN ACCESS Land cover change analysis and impacts of deforestation on the climate of District Mansehra, Pakistan Dania Amjad1, Sumaira Kausar*2, Rana Waqar3, Faiza Sarwar4 1Department of Geography, Punjab University, Lahore, Pakistan 2Lecturer Punjab University, Lahore, Pakistan 3GIS Specialists, Al Jabar Sign Abu Dhabi, UAE 4Geography Department, Punjab University, Lahore, Pakistan Article published on June 30, 2019 Key words: GIS, Remote Sensing, Deforestation, Climate Change, Landcover Analysis, Landsat imagery, Temperature, Precipitation, Time Series Analysis, Supervised, Mansehra, Pakistan. Abstract In this study, district Mansehra, Pakistan was chosen as the study area. The main objectives of this research are to assess the extent and the changes in the rate of deforestation in Mansehra since past 20 years. It also examine the impacts of deforestation on the Climate by establishing and mapping the magnitude and rates of land cover changes that had occurred in the study area. Landsat satellite images were taken as secondary data and they were foremost for the classification process. Remote sensing data together with GIS techniques have made it conceivable to display and oversee remotely detected information in various scales. The images taken for classification are Landsat 5 TM for the year 1998 and 2008 and from Landsat 8 OLI/TIRS TM for the year 2017. Climatic data from 1988 to 2017 was collected from Pakistan Meteorological Department (PMD) of Mansehra District. The Forest Cover was 14% (601 Sq. -

To Open Bankislami Pakistan Limited Details

S.No Branch Name Address City Province Supply Bazar 1 Plot # 195-207, Khasra # 2302-2305, Abbottabad Business Complex, Moza Shaikul Bandi, Amir Shaheed Road, Supply Bazar, Manshera Road, Abbottabad. Abbottabad KPK 2 Arifwala Plot No.115, H-Block, Thana Bazar, Arifwala Arifwala Punjab 3 Attock Omair Arcade, Opposite Peoples Colony, Main Attock Road, Attock. Attock Punjab 4 Ghourghusti Miskeenabad, Ghourghusti, Tehsil Hazro, District Attock Attock Punjab 5 Badin Mani Quaid-e-azam Road, Near Qazia Wah, Badin Badin Sindh 6 Golarchi Plot No. A-4, Golarchi Town, Taluka Shaheed Fazil Rao, District Badin Badin Sindh 7 Satellite Town Plot # 53-C, Commercial Area, Satellite Town, Bahawalpur Bahawalpur Punjab 8 Circular Road Block No. 915, Circular Road Bahawalpur. Bahawalpur Punjab 9 Balakot Plot, Khasra No.3626/1046, Moza Balakot,Tehsil Balakot, District Mansehra Balakot KPK 10 Batagram Khasra No.792, Moza Ajmairah, Tehsil & District Batgram. Batagram KPK 11 Batkhela Main Bazar Batkhela, Tehsil Sawat Ranizai, District Malakand Batkhela KPK 12 Beesham Plot Khasra No.583, Moza Butyal, Main Road Besham, Tehsil Besham, District Shangla Beesham KPK 13 Booni Booni Bazar, Village & P.O Booni, Tehsil Mastaj, District Chitral Booni KPK 14 Chaksawari, AJK Main Mirpur Road, Near Attock Petrol Pump, Chaksawari, District Mirpur, Azad Kashmir Chaksawari AJK 15 Chakwal Khasra # 4516 Jhelum Road Chakwal. Chakwal Punjab 16 Chaman Khasra # 208 & 209, Mall Road, Chaman Chaman Balochistan 17 Chichawatni Plot No.146, Khatooni # 239, G.T. Road, Chichawatni Chichawatni Punjab 18 Chilas Main Bazar, DC Chowk, Rani Road Chillas, District Diamer. Chilas KPK 19 Chiniot 1- A Shahra-e- Quaid Azam , Chiniot. -

Contextualizing Buddhism: Exploring the Limits of Buddhist Survivability in High Altitude Valleys in District Mansehra, Pakistan Shakirullah, Junaid Ahmad, Haq Nawaz

Ancient Pakistan, Vol. XXVII (2016) 35 Contextualizing Buddhism: Exploring the Limits of Buddhist Survivability in High Altitude Valleys in District Mansehra, Pakistan Shakirullah, Junaid Ahmad, Haq Nawaz Abstracts: Mansehra, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province, Pakistan, being located on the ancient Silk Route has played an instrumental role in the ancient trade, commerce and development of Buddhism as well. The region is a pivot between the China and Central Asia. Asoka recognized it in the 3rd century BC by carving 14 edicts here, and became central to the spread of Buddhism to Central Asia and China. It has been revealed that no Buddhist site existed at altitude of 2000 meter and above, equally not mentioned in Buddhist narratives. Recent archaeological explorations exposed hundreds of Buddhist sites in the region revealing the survivability and availability of Buddhist sites mainly on the trade routes. This paper systematically explores the existence of Buddhist monuments in Mansehra coping with natural and cultural landscapes. Keywords: Buddhist monuments, Explorations, Survivability The valleys of District Mansehra in Khyber 124; 1991: 152-163), and their absence in Pakhtunkhwa Province, Pakistan, have been Mansehra. This paper systematically explores strategically located on the ancient Silk Routes the existence of Buddhist monuments in District and have been instrumental in the promotion of Mansehra and their relationships with natural trade, commerce and Buddhism in the past. The and cultural landscapes. We tentatively argue region derives its importance from its location that Buddhist monuments in District Mansehra, between the valleys of Kashmir, Gilgit-Baltistan, were present in regions which were more China and Central Asia. King Asoka, who accessible and were on trade routes, and that the erected his 14 edicts at the crossroads at the city Buddhist did not explore and live in the of Mansehra (Shama 2002: 87-103), recognized extraordinarily beautiful and calm valleys the importance of this region in the 3rd century beyond 2000 meters above mean sea level. -

Evaluation of UNDP's Earthquake Programme

Evaluation of UNDP's Earthquake Programme Final Report (Draft) Javed A.Malik (Team Leader) Salma Omar Krishna Vatsa December 2008 Table of contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................... - 4 - SECTION ONE: OVER ALL EVALUATION SUMMERY ........................................................... - 5 - 1. BACKGROUND ...................................................................................................................... - 6 - 2. SCOPE AND RATIONALE OF THE EVALUATION.............................................................................. - 6 - 3. APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY OF ANALYSIS ............................................................................ - 7 - 4. TOOLS USED FOR THE EVALUATION EXERCISE ............................................................................. - 9 - 5. FINDINGS........................................................................................................................... - 11 - Relief Phase ...................................................................................................................... - 11 - Early Recovery .................................................................................................................. - 14 - SECTION TWO: PROJECT WISE ANALYSIS ......................................................................... - 17 - OVERALL COORDINATION IN THE INITIAL PHASE ........................................................................... - 18 - Relevance ........................................................................................................................ -

Download CV in PDF Format

Dr. ASAD ULLAH Flat No. C-32, Gate No. 5, Professor Colony, The University of Agriculture Peshawar. Mob-03005824733. Summary: Twenty years working experience in Government & donor assisted projects with reference to NRM, community development, capacity building and participatory planning monitoring and evaluation. As an academician, remained lecturer in Sociology at Kohat University of Science and Technology and The University of Agriculture Peshawar for six years and as Assistant Professor in Department of Rural Sociology the University of Agriculture till date and taught subject of Sociology at Post Graduate level besides supervising research. In NRM sector, I worked as a team member in preparation of a number of Resource Management Plans, conducted training programs at community level and research on the dependency of communities on Natural Resources for their livelihood. I have played an important role in the coordination of different teams to develop pilot Village Plans focused to formulate interventions based on Human Rights, Poverty Alleviation, Capacity Building and Decentralization; and participated actively in the elaboration of the concept “Participatory Resource Management”. I have performed “Participatory Monitoring & Evaluation”, “Livelihood Strategies”, “Capacity Building”, “Participatory Technology Development”, “People Centered Approach”, preparation of PC-1/project proposal etc. Also devised a REDD+ benefit sharing strategy for KP Forest Department under the umbrella of REDD+ project (KP section). In addition, assessed carbon stock in agriculture sector of KP province and analyzed risks and benefits of REDD+ under PFI lead REDD+ Project. Remained tem member in third party evaluation via SWOT analysis of AJK Forest Department and AKLASC, and Insaf food security Program (KP component). -

El 710 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized

El 710 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized - v 7 , , I SJ7- k?KS -Aj Public Disclosure Authorized ,''.-F C -- " I - Public Disclosure Authorized Rural Housing Project (World Bank -ERRA) Limited Enviornmental Assessment 57 Environment Protection Cell-ERRA Limited Environmental Assessment for Rural Housing in Earthquake affected Area Environmental Protection Cell ERRA July 2007 EARTHQUAKE RECONSTRUCTION AND REHABILITATION AUTHORITY (ERRA) Rural Housing Project (World Bank -ERRA) Limited Enviornmental Assessment Environment Protection Cell-ERRA The world's poor depend critically on fertile soil, clean water and healthy ecosystems for their livelihoods. Their well-being is directly linked to sustainable use of natural resources. Consequently, environmental degradation undermines the capacity of poor people to meet their daily needs. Sustainable use and restoration of natural resources is challenge for the ERRA and all partner organizations during reconstruction and rehabilitation. (Adopted from UNEP) Rural Housing Project (World Bank -ERRA) Limited Environmental Assessment Report Environment Protection Cell of Earthquake Reconstruction and Rehabilitation Authority EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The earthquake of October 8, 2005, left 73,000 dead and about as many injured while 2.8 million people were left shelterless. It brought a greater damage to whole infrastructure including roads, health facilities, different institutional facilities and above all the sever damages of about 600,000 houses including scattered waste rural and urban 2 houses in area of 30,000 Km expanding North East of Pakistan and State of Azad Jammun and Kashmir. To provide the shelter at transitional level and challenge of reconstruction of private houses was one of the first step that ERRA took on. Population in rural area was more vulnerable due to access to them for relief and rehabilitation. -

Province Wise Provisional Results of Census - 2017

PROVINCE WISE PROVISIONAL RESULTS OF CENSUS - 2017 ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS POPULATION 2017 POPULATION 1998 PAKISTAN 207,774,520 132,352,279 KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA 30,523,371 17,743,645 FATA 5,001,676 3,176,331 PUNJAB 110,012,442 73,621,290 SINDH 47,886,051 30,439,893 BALOCHISTAN 12,344,408 6,565,885 ISLAMABAD 2,006,572 805,235 Note:- 1. Total Population includes all persons residing in the country including Afghans & other Aliens residing with the local population 2. Population does not include Afghan Refugees living in Refugee villages 1 PROVISIONAL CENSUS RESULTS -2017 KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA District Tehsil POPULATION POPULATION ADMN. UNITS / AREA Sr.No Sr.No 2017 1998 KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA 30,523,371 17,743,645 MALAKAND DIVISION 7,514,694 4,262,700 1 CHITRAL DISTRICT 447,362 318,689 1 Chitral Tehsil 278,122 184,874 2 Mastuj Tehsil 169,240 133,815 2 UPPER DIR DISTRICT 946,421 514,451 3 Dir Tehsil 439,577 235,324 4 *Shringal Tehsil 185,037 104,058 5 Wari Tehsil 321,807 175,069 3 LOWER DIR DISTRICT 1,435,917 779,056 6 Temergara Tehsil 520,738 290,849 7 *Adenzai Tehsil 317,504 168,830 8 *Lal Qilla Tehsil 219,067 129,305 9 *Samarbagh (Barwa) Tehsil 378,608 190,072 4 BUNER DISTRICT 897,319 506,048 10 Daggar/Buner Tehsil 355,692 197,120 11 *Gagra Tehsil 270,467 151,877 12 *Khado Khel Tehsil 118,185 69,812 13 *Mandanr Tehsil 152,975 87,239 5 SWAT DISTRICT 2,309,570 1,257,602 14 *Babuzai Tehsil (Swat) 599,040 321,995 15 *Bari Kot Tehsil 184,000 99,975 16 *Kabal Tehsil 420,374 244,142 17 Matta Tehsil 465,996 251,368 18 *Khawaza Khela Tehsil 265,571 141,193