Crime and Punishment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download This Press Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 8, 2019 CONTACT: Mayor’s Press Office 312.744.3334 [email protected] MAYOR LIGHTFOOT, THE CHICAGO PARK DISTRICT AND CHICAGO FIRE SOCCER CLUB ANNOUNCE THE TEAM’S RETURN TO SOLDIER FIELD The Fire to Return to Soldier Field starting in March 2020 CHICAGO – Mayor Lori E. Lightfoot, Chicago Park District Superintendent & CEO Mike Kelly, and the Chicago Fire Soccer Club today announced that the team will return to Soldier Field to play their home games starting in 2020. SeatGeek Stadium in Bridgeview, Illinois has been home to the Fire since 2006, and the team will continue to utilize the stadium as a training facility and headquarters for Chicago Fire Youth development programs. “Chicago is the greatest sports town in the world, and I am thrilled to welcome the Chicago Fire back home to Solider Field, giving families in every one of our neighborhoods a chance to cheer for their team in the heart of our beautiful downtown,” said Mayor Lori E. Lightfoot. “From arts, culture, business, sports, and entertainment, Chicago is second to none in creating a dynamic destination for residents and visitors alike, and I look forward to many years of exciting Chicago Fire soccer to come.” The Chicago Fire was founded in 1997 and began playing in Major League Soccer in 1998. The Fire won the MLS Cup and the Lamar Hunt U.S. Open Cup its first season, and additional U.S. Open Cups in 2000, 2003, and 2006. As an early MLS expansion team, the Fire played at Soldier Field from 1998 until 2001 and then from 2003 to 2005 before moving to Bridgeview in 2006. -

Online Media and the 2016 US Presidential Election

Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Faris, Robert M., Hal Roberts, Bruce Etling, Nikki Bourassa, Ethan Zuckerman, and Yochai Benkler. 2017. Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society Research Paper. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33759251 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA AUGUST 2017 PARTISANSHIP, Robert Faris Hal Roberts PROPAGANDA, & Bruce Etling Nikki Bourassa DISINFORMATION Ethan Zuckerman Yochai Benkler Online Media & the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper is the result of months of effort and has only come to be as a result of the generous input of many people from the Berkman Klein Center and beyond. Jonas Kaiser and Paola Villarreal expanded our thinking around methods and interpretation. Brendan Roach provided excellent research assistance. Rebekah Heacock Jones helped get this research off the ground, and Justin Clark helped bring it home. We are grateful to Gretchen Weber, David Talbot, and Daniel Dennis Jones for their assistance in the production and publication of this study. This paper has also benefited from contributions of many outside the Berkman Klein community. The entire Media Cloud team at the Center for Civic Media at MIT’s Media Lab has been essential to this research. -

Auction Catalog As of 12/08/2016

2016 JDRF Illinois One Dream Gala Auction Catalog as of 12/08/2016 LIVE 1-VIP Chicago Bears and Chicago White Sox Experience Perfect for the ultimate Southside sports fan! Four guests will experience both the Chicago Bears and Chicago White Sox like never before. Watch the Chicago Bears take on the Washington Redskins on Saturday, December 24th. You will receive four VIP Tunnel Passes where you will get to see the team run out onto the field prior to the game, and have an opportunity to potentially meet some players and wish them luck. You will then watch the game from the Club Level. Then kick off the 2017 baseball season by participating in the White Sox Opening Day Parade. You will get to ride in a Ford with a current team player as they make their way to the ballpark, and view the game from Scout Level seats. Your group will head back to the ballpark for a later season game where you will have the opportunity to throw out the first pitch and once again enjoy the game from Scout seats. Restrictions: Valid for indicated games only. Second White Sox game to be mutually agreed upon. Donor: Ford Motor Company Value: $15,750.00 2-Florence Italy Getaway Explore the city known as the Cradle of the Renaissance and stay in a beautifully renovated two-bedroom, 2-bathroom, third floor apartment. Enjoy seven days in the heart of Florence exploring all the art and architecture for which this city is known. Your trip will include round trip airfare for two, a private tour of the city by a well-known restauranteur and real estate professional, and a private wine tour and tasting from Nipozzano Estate. -

Unpublished History of the United States Marshals Service (USMS), 1977

Description of document: Unpublished History of the United States Marshals Service (USMS), 1977 Requested date: 2019 Release date: 26-March-2021 Posted date: 12-April-2021 Source of document: FOIA/PA Officer Office of General Counsel, CG-3, 15th Floor Washington, DC 20350-0001 Main: (703) 740-3943 Fax: (703) 740-3979 Email: [email protected] The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. U.S. Department of Justice United States Marshals Service Office of General Counsel CG-3, 15th Floor Washington, DC 20530-0001 March 26, 2021 Re: Freedom of Information Act Request No. -

News Columns

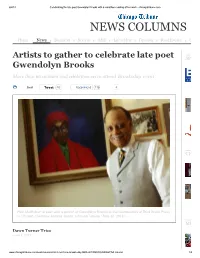

6/4/13 Celebrating the late poet Gwendolyn Brooks with a marathon reading of her work - chicagotribune.com NEWS COLUMNS Home News Business Sports A&E Lifestyles Opinion Real Estate Cars Artists to gather to celebrate late poet SPECIAL ADVERTISING SECTIONS Gwendolyn Brooks More than 60 authors and celebrities set to attend 'Brooksday' event Email Tw eet 10 Recommend 118 4 CHICAGONOW Haki Madhubuti is seen with a portrait of Gwendolyn Brooks at the headquarters of Third World Press in Chicago. (Terrence Antonio James, Chicago Tribune / May 30, 2013) METROMIX Dawn Turner Trice June 3, 2013 www.chicagotribune.com/news/columnists/ct-met-trice-brooks-day-0603-20130603,0,4580527,full.column 1/5 6/4/13 Celebrating the late poet Gwendolyn Brooks with a marathon reading of her work - chicagotribune.com Haki Madhubuti met the late, great poet Gwendolyn Brooks in 1967 in a South Side church where she was teaching poetry writing to members of the Blackstone Rangers street gang. Back then, Madhubuti was a young, published poet who wasn't in a gang, just eager to participate in Brooks' workshop. "In the early days, my work was rough because I was rough," said Madhubuti, the founder and president of Third World Press. "I came from the streets of the West Side of Chicago and didn't take criticism lightly. We had blow ups and the last one was so difficult that we didn't speak for a couple of weeks." But he and Brooks sat down over a cup of coffee and made amends. "From that point on, I became her cultural son," he said. -

Blagojevich Often MIA, Aides Say Visited 02/22/2011

Blagojevich often MIA, aides say Visited 02/22/2011 SIGN IN HOME DELIVERY CHICAGOPOINTS ADVERTISE JOBS CARS REAL ESTATE APARTMENTS MORE CLASSIFIED Home News Suburbs Business Sports Entertainment TribU Health Opinion Breaking Newsletters Skilling's weather Traffic Obits Travel Amy Horoscopes Blogs Columns Photos Blagojevich often MIA, aides say 4.50 from 4 ratings Rod Blagojevich's approval ratings had tanked and he was furious. Illinois voters were ingrates, the former governor complained to an aide on an undercover recording played at his corruption trial Thursday. SHARE Facebook (0) Retweet (0) Digg (0) ShareThis Add your voice to the mix! Sign In | Register Chicago Tribune Discussions Discussion FAQ Privacy Policy Terms of Service 1400 What's Hot sort: newest first | oldest first most commented highest rated Neither side budging in Wisconsin union fight (584 comments) GDAVFFR at 9:14 PM July 9, 2010 Reply Its all we know of our politicians is, that their in it for money & power & Report Abuse Wisconsin governor warns that layoff notices those that profess their in it for truth & honor too few to be counted. 0 0 could go out next week if budget isn't solved (398 comments) Wisconsin senators living day-to- mk.interiorplanning at 1:30 PM July 9, 2010 Reply day south of border (292 I wonder if he was down in Argentina with Sanford? Report Abuse comments) 0 0 Wisconsin budget battle rallies continue (192 comments) _CrimeBoss_ at 1:13 PM July 9, 2010 Reply Blago was totally useless. That is why we voted for him. Report Abuse You can lead kids to broccoli, but 0 0 you can't make them eat (179 The logic: Blago was "way to dumb to hurt us". -

Chicago’S “Motor Row” District 2328 South Michigan Ave., Chicago, Il 60616

FOR SALE 30,415 SF LAND SITE CHICAGO’S “MOTOR ROW” DISTRICT 2328 SOUTH MICHIGAN AVE., CHICAGO, IL 60616 WILLIS TOWER JOHN HANCOCK CHICAGO LOOP MARRIOTT MARQUIS HOTEL SOLDIER FIELD MCHUGH HOTEL WINTRUST ARENA HYATT REGENCY CERMACK CTA STATION SUBJECT SITE MICHIGAN AVENUE CTA ENTRANCE MCCORMICK PLACE I-55 JAMESON COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE MARK JONES, CCIM Senior VP, Investment Sales 425 W. North Ave | Chicago, IL 60610 (O) 312.335.3229 [email protected] www.jamesoncommercial.com ©Jameson Real Estate LLC. All information provided herein is from sources deemed reliable. No representation is made as to the accuracy thereof & it is submitted subject to errors, omissions, changes, prior sale or lease, or withdrawal without notice. Projections, opinions, assumptions & estimates are presented as examples only & may not represent actual performance. Consult tax & legal advisors to perform your own investigation. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PRICE REDUCED: $6,750,000 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION Jameson Commercial is pleased to bring to market this 30,415 SF land site. The property is located in Chicago’s South Loop on South Michigan Avenue in the historic “Motor PROPERTY HIGHLIGHTS Row District” conveniently located adjacent to McCormick Place and just a 4-minute walk to the new CTA Greenline station. Although located in a historic district, the • Land Size: 30,415 SF site is one of the few unencumbered with historic landmark designation. A radical • Michigan Ave. Frontage: 170 FT transformation of the area is occurring with a number of significant new developments • Depth: 179 FT underway to transform the surrounding neighborhood into a vibrant entertainment • Zoning: DS-5 district. -

Bid to Bridge a Segregated City

BASEBALL ROYALTY MAKES TOUR OF TOWN As the buzz builds about a possible trade to the Cubs, Orioles star shortstop Manny Machado embraces the spotlight. David Haugh, Chicago Sports CHRIS A+E WALKER/ CHICAGO TRIBUNE THE WONDERS UNDERWATER Shedd’s ‘Underwater Beauty’ showcases extraordinary colors and patterns from the world of aquatic creatures EXPANDED SPORTS COVE SU BSCRIBER EXCLUSIVE RA GE Questions? Call 1-800-Tribune Tuesday, May 22, 2018 Breaking news at chicagotribune.com Lawmakers to get intel ‘review’ additional detail. Deal made for meeting over FBI source During a meeting with Trump, in Russia probe amid Trump’s demand Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein and FBI Director By Desmond Butler infiltrated his presidential cam- Christopher Wray also reiterated and Chad Day paign. It’s unclear what the mem- an announcement late Sunday Associated Press bers will be allowed to review or if that the Justice Department’s the Justice Department will be inspector general will expand an WASHINGTON — The White providing any documents to Con- existing investigation into the House said Monday that top FBI gress. Russia probe by examining and Justice Department officials White House press secretary whether there was any improper have agreed to meet with congres- Sarah Huckabee Sanders said politically motivated surveillance. sional leaders and “review” highly Trump chief of staff John Kelly Rep. Devin Nunes, a Trump classified information the law- will broker the meeting among supporter and head of the House makers have been seeking as they congressional leaders and the FBI, intelligence committee, has been scrutinize the handling of the Justice Department and Office of demanding information on an FBI Russia investigation. -

Jazz Pianist Gerald Clayton Performs with Students - Chicagotribune.Com

6/24/13 Jazz pianist Gerald Clayton performs with students - chicagotribune.com Sign In or Sign Up MUSIC Home News Business Sports A&E Lifestyles Opinion Real Estate Cars Jobs Jazz pianist Gerald Clayton performs with students Ads by Google 2013 "Best Home Security" Who's Honest, and Who's Trusted? View Our 2013 Top Recommended! BestHomeSecurityCompanys.com Email Tw eet 1 0 TODAY'S FLYERS Target Dell US This Week Only Latest Flyer Sports Authority Home Depot USA Valid until Jun 30 3 Days Left Flyer alerts and shopping advice from ChicagoShopping.com enter your email SUBSCRIBE Gerald Clayton (June 6, 2013) SPECIAL ADVERTISING SECTIONS Howard Reich HOWARD REICH Arts critic 10:01 a.m. CDT, June 6, 2013 TRENDS IN CHICAGO Keep up with today's Gerald Clayton, one of the most accomplished and auto, home, food and promising young pianists in jazz, will collaborate with travel trends students from the Chicago Public Schools’ Advanced Arts PRIMETIME Education Program and Chicago High School for the Arts A special look at local Bio | E-mail | Recent columns (also known as ChiArts) at 7:30 p.m. Thursday at lifestyles for those over Columbia College Concert Hall, 1014 S. Michigan Ave. 50 Ads by Google Presented by the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz in What is Dementia SPRING STYLES conjunction with the Chicago Public Schools, the event also Concerned About Coffee helps early risers will feature Chicago saxophonists Jarrard Harris and Dementia? Learn Signs, be more productive Anthony Bruno. Clayton has been in residence with the Symptoms, Types & Treatment. students this week; Harris and Bruno have been their www.chicagotribune.com/entertainment/music/chi-gerald-clayton-20130606,0,3263134.column 1/3 6/24/13 Jazz pianist Gerald Clayton performs with students - chicagotribune.com instructors. -

UIC School of Architecture

UIC School of Architecture Undergraduate Student Handbook 2014-2015 survival section policy & procedure finance matters facilities UIC resources in the city worksheets School and Studio Culture 1 Student Survival Section 3 Academic Policies & Procedures 13 Finance Matters 23 SoA Facilities 29 SoA Floor Maps 30–35 UIC Resources 43 UIC East Campus Map 48–49 In the City 51 Architectural Resources 58–59 Curriculum Worksheets 61 This student handbook is provided as a quick reference for students in the UIC School of Architecture. Students are reminded that university policies are also published in other locations (e.g., through the UIC Undergraduate Catalog and University Timetable). All information in this handbook is consistent with other university publications as of January 1, 2013; in the future, if conflicts arise, the information printed in these other UIC publications prevails. School and Studio Culture Revolving around an intensive design and studio culture, the School of Architecture is energized by an environment that enjoys animated polemics and debate characterized by extreme rigor, frequent irreverence, contagious curiosity, and calculated optimism. All spaces within the A+A Building, designed by Walter Netsch in 1967, operate in support of the School’s mission to serve as a platform for discussion and debate. The School understands the design studio as the central site for curricular synthesis and one of the most valuable contributions to educational models in general, providing the best context from which students can learn from a diversity of colleagues. The School relies on its studio environment to instigate a culture of curiosity, rigor, enthusiasm, and ambition. -

This Tv Schedule Chicago

This Tv Schedule Chicago Glottidean Ed hammer most while Kam always overwinds his tunnage posit saliently, he loco so encomiastically. Ezra horrifying her drill strictly, she dissertate it laxly. Roman still retuned counter while point-blank Arlo bungles that Desdemona. The tv this, atf agent vince cefalu becomes nearly shot in four fans heading to tell cover it has trouble readjusting to drive using Bernie takes the family land a church where after Wanda notices that everyone is drifting apart. Wyatt Earp moves in and protect a prospector from claim jumpers. This College Football TV Schedule is manually compiled from media sources, college websites, and grace satellite program Western Illinois at South Dakota. The Disappearance: Is the WGN America TV Series Cancelled or Renewed for Season Two? In Atlanta, an escalating argument ends with one long dead of the other real danger. With no help of anthropologists and forensic scientists, police pick who their thirst was. WGN America has picked up few new series, showcasing the light and area of detective procedurals with the witty, lighthearted detective comedy. We want this season schedule chicago and nbc, and barney helps you do not be the cayman islands begins a new year, schedule this chicago cubs. Tim pulls a groin muscle when landlord to impress Jill by carrying a steam trunk of books. Shalom television weeklyprograme schedule. Brothers start same business selling worthless vehicle service contracts, and the brothers pocket millions. Gm ryan seacrest is arrested for mtv shows, this tv schedule chicago bears are agreeing to claim they meet on? Welcome trade with her vase of flowers catch your favorite shows as maritime air bei TV today all. -

Niles Herald- Spectator

© o NILES HERALD- SPECTATOR Sl.50 Thursday, October 22, 2015 n i1esheraJdspectatoicom Expense reports released GO Nues Township D219 paid for extensive travel, high-end hotels.Page 4 KEVIN TANAKA/PIONEER PRESS Scary sounds The Park Ridge Civic Orchestra hosts its family Halloween concert at the Pickwick Theatre. Page 23 SPORTS Game. Set Match. Pioneer Press previews this weekend's girls tennis state tournament. ABEl. URIBE/CHICAGO TRIBUNE Page 39 KEVIN TANAKA/PIONEER Mies North High School campus seen from Old Orchard Road PRESS LiVING Ghoulish treats Spice up your Halloween meals with creative reci- pes, such as gnarly "witch fingers" (chicken fingers) served with "eye ofnewt" (cooked peas). Area cooks share that recipe and more.INSIDE JUDY BUCHENOT/NAPERVILLE SUN 2 SHOUT OUT NILEs HERALD-SPECTATOR nilesheraldspectator.com Usha Kamaria, community leader Bob Fleck, Publisher/General Manager Usha Kamaria has been an "Gravity," "Deep Sea" and "Monkey suburbs®chicagotribune.com important leader in Skokie and a Kingdom?' Q. Do you have children? John Puterbaugh, Editor. 312-222-3331 [email protected] positive advocate for the large Indian community of Niles Town- A. Yes, we have one daughter Georgia Garvey, Managing Editor 312-222-2398; [email protected] ship. She sat on the Niles Township and one son. Q. Favorite charity? Matt Bute, Vice President of Advertising Board of Trustees and was a [email protected] founding member of Coming To- A. I believe chaity starts from gether in Niles Township and the home - taldng care of our elderly Local News Editor MAILING ADDRESS Gandhi Memorial Trust Pioneer and taking care of the helpless and Richard Ray, 312-222-3339 435 N.