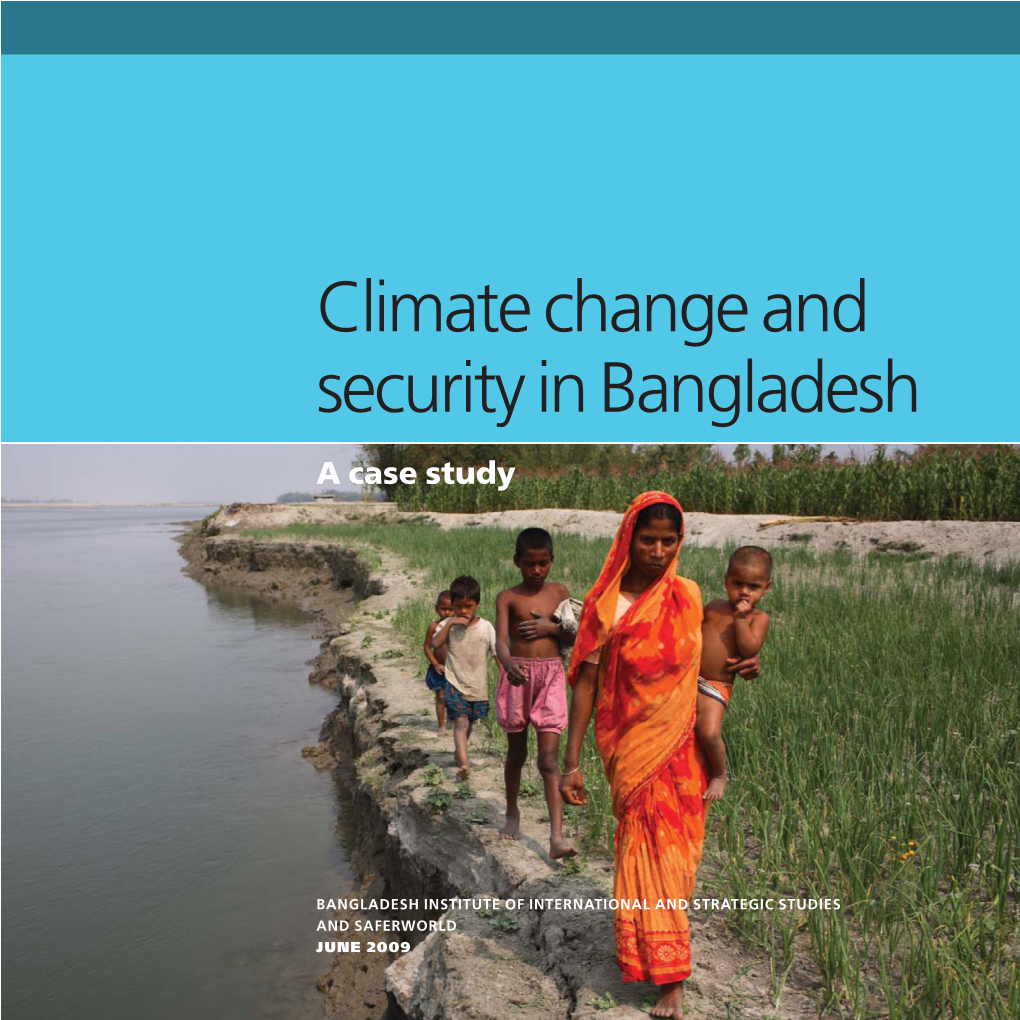

Climate Change and Security in Bangladesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bangladesh - Researched and Compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on Friday 20 November 2015

Bangladesh - Researched and compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on Friday 20 November 2015 Treatment of Jamaat-e-Islami/Shibir(student wing) by state/authorities In June 2015 a report published by the United States Department of State commenting on events of 2014 states: “ICT prosecutions of accused 1971 war criminals continued. No verdicts were announced until November, when the ICT issued death sentences in separate cases against Motiur Rahman Nizami and Mir Quasem Ali. At the same time, the Supreme Court Appellate Division upheld one of two death sentences against Mohammad Kamaruzzaman. All three men were prominent Jamaat leaders, and Jamaat called nationwide strikes in protest” (United States Department of State (25 June 2015) 2014 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – Bangladesh). This report also states: “On August 10, Shafiqul Islam Masud, assistant secretary of the Jamaat-e-Islami Dhaka City Unit, was arrested, charged, and held in police custody with 154 others for arson attacks and vandalism in 2013. He was arrested and held four additional times in August and September 2014. According to a prominent human rights lawyer, Masud's whereabouts during his detentions were unknown, and lawyers were not allowed to speak with him. Defense lawyers were not allowed to speak before the court during his September 23 and 25 court appearances” (ibid). This document also points out that: “In some instances the government interfered with the right of opposition parties to organize public functions and restricted the broadcasting of opposition political events. Jamaat's appeal of a 2012 Supreme Court decision cancelling the party's registration continued” (ibid). -

Planning and Costing Agriculture's Adaptation to Climate Change in The

Planning and costing agriculture’s adaptation to climate change in the salinity-prone cropping system of Bangladesh Khandaker Mainuddin, Aminur Rahman, Nazria Islam and Saad Quasem, Bangladesh Centre for Advanced Studies October, 2011 Planning and costing agriculture’s adaptation to climate change in the salinity-prone cropping system of Bangladesh Contacts: Khandaker Mainuddin (Senior Fellow), Aminur Rahman, Nazria Islam and Saad Quasem, Bangladesh Centre for Advanced Studies (BACS), House #10, Road #16A, Gulshan 01, Dhaka 1212 • Tel: (88-02) 8852904, 8852217, 8851986, 8851237 • Fax: (88-02) 8851417 • Website: www.bcas.net • Email [email protected] International Institute for Environment and Development, IIED, 80-86 Gray’s Inn Road, London WC1X 8NH, UK • Tel: +44 (0)20 3463 7399 • Fax: +44 (0)20 3514 9055 • Email: [email protected] Citation: Mainuddin, K., Rahman, A., Islam, N. and Quasem, S. 2011. Planning and costing agriculture’s adaptation to climate change in the salinity-prone cropping system of Bangladesh. International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), London, UK. This report is part of a five-country research project on planning and costing agricultural adaptation to climate change, led by the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI) and the Global Climate Adaptation Partnership (GCAP). This project was funded by the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) under the Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security Policy Research Programme. All omissions and inaccuracies in this document are the responsibility of the authors. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of the institutions involved, nor do they necessarily represent official policies of DFID - 1 - Planning and costing agriculture’s adaptation to climate change in the salinity-prone cropping system of Bangladesh Table of contents Acronyms and abbreviations ................................................................................................... -

I Community Perceptions and Adaptation to Climate Change In

School of Media, Culture and Creative Arts Department of Social Sciences and International Studies Community Perceptions and Adaptation to Climate Change in Coastal Bangladesh M. Mokhlesur Rahman This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Curtin University March 2014 i Dedicated to My parents ii Declaration To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgement has been made. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. Signature: ………………………………………………….. Date: ………1 January 2015…………………………………………. iii Acknowledgements The huge task of completing a doctoral thesis obviously demands the support and encouragement of many - from family, friends, and colleagues and more importantly from supervisors. Throughout my journey towards this accomplishment my wife Runa has been the great source of encouragement to fulfill the dream of my father who wanted to see all his children become highly educated but who died when I was in primary school. My mother who died at 101 in October 2013 allowed me to come to Australia in my effort to fulfill my father’s dream. My children were always considerate of the separation from my family for the sake of my study but were curious about what it could bring me at the end. Professor Bob Pokrant, my supervisor, all along has been a guide and often a critic of my quick conclusions on various aspects of the interim research findings. He always encouraged me to be critical while reaching conclusions on issues and taught me that human societies consist of people caught up in complex webs of socio- political relations and diverse meanings, which become ever more complex when we seek to embed those relations and meanings within coupled social ecological systems. -

Profitability Analysis of Bagda Farming in Some Selected Areas of Satkhira District

Progress. Agric. 20(1 & 2) : 221 – 229, 2009 ISSN 1017-8139 PROFITABILITY ANALYSIS OF BAGDA FARMING IN SOME SELECTED AREAS OF SATKHIRA DISTRICT A. N. M. Wasim Feroz1, M. H. A. Rashid2 and Mahbub Hossain3 Department of Agricultural Economics, Bangladesh Agricultural University Mymensingh 2202, Bangladesh ABSTRACT This study aimed at examining the relative profitability of shrimp production in some areas of Satkhira district. Farm level data were collected through interviewing 60 randomly selected farmers. Mainly tabular analysis was done to achieve the major objectives of the study. Cobb-Douglas production function was used to estimate the contribution of key variables to the production process of shrimp farming. Analysis of costs and returns showed that per hectare total cost of shrimp production was Tk. 1,06,791.00 and net return from shrimp production was Tk. 84,023.80. Production function analysis proved that inputs such as fry, human labour, fertilizers, manure, lime etc. had positive impact on output. The study also identified some problems and suggested some possible steps to remove these problems. If these problems could be solved bagda production would possibly be increased remarkably in the study area as well as in Bangladesh. Key words : Year-round bagda farming, Profitability, Functional analysis INTRODUCTION Agriculture sector contributes 21% (BER, 2008) to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of Bangladesh economy as a whole of which fisheries sector’s share is 4.73%. Shrimp farming and related activities contribute significantly to the national economy of Bangladesh. The main areas of contribution are export earning and employment generation through on farm and off-farm activities. -

Evacuation Scenarios of Cyclone Aila in Bangladesh

Progress in Disaster Science 2 (2019) 100032 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Progress in Disaster Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/pdisas Regular Article Evacuation scenarios of cyclone Aila in Bangladesh: Investigating the factors influencing evacuation decision and destination ⁎ Gulsan Ara Parvin a, ,MasashiSakamotob, Rajib Shaw c, Hajime Nakagawa a, Md Shibly Sadik d a Disaster Prevention Research Institute, Kyoto University, Japan b Pacific Consultant, Tokyo, Japan c Keio University, Japan d Department of Civil and Earth Resources Engineering, Kyoto University, Japan ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: It is well known that Bangladesh is one of the most disaster-prone countries in the world. Especially, climate related Received 7 February 2019 disasters like flood and cyclone are most common in Bangladesh. Among all disasters, considering the loss of lives cy- Received in revised form 9 May 2019 clones impose the most severe impacts in Bangladesh. There are number of studies focusing loss and damages associ- Accepted 17 June 2019 ated with different cyclones in Bangladesh. Researchers also identified different factors related to evacuation decision Available online 29 June 2019 making process. However, in case of Bangladesh, analyzing people's experience during devastating cyclone, only a few researches tried to identify the factors that guided them to take evacuation decision and to select evacuation destina- Keywords: Evacuation decision tion. With empirical study on 200 people of Gabura Union that were the worst affected during cyclone Aila, this re- Destination search analyzes how different groups of people are influenced by different factors and take evacuation decision and Factors finally choose their evacuation destination. -

List of 100 Bed Hospital

List of 100 Bed Hospital No. of Sl.No. Organization Name Division District Upazila Bed 1 Barguna District Hospital Barisal Barguna Barguna Sadar 100 2 Barisal General Hospital Barisal Barishal Barisal Sadar (kotwali) 100 3 Bhola District Hospital Barisal Bhola Bhola Sadar 100 4 Jhalokathi District Hospital Barisal Jhalokati Jhalokati Sadar 100 5 Pirojpur District Hospital Barisal Pirojpur Pirojpur Sadar 100 6 Bandarban District Hospital Chittagong Bandarban Bandarban Sadar 100 7 Comilla General Hospital Chittagong Cumilla Comilla Adarsha Sadar 100 8 Khagrachari District Hospital Chittagong Khagrachhari Khagrachhari Sadar 100 9 Lakshmipur District Hospital Chittagong Lakshmipur Lakshmipur Sadar 100 10 Rangamati General Hospital Chittagong Rangamati Rangamati Sadar Up 100 11 Faridpur General Hospital Dhaka Faridpur Faridpur Sadar 100 12 Madaripur District Hospital Dhaka Madaripur Madaripur Sadar 100 13 Narayanganj General (Victoria) Hospital Dhaka Narayanganj Narayanganj Sadar 100 14 Narsingdi District Hospital Dhaka Narsingdi Narsingdi Sadar 100 15 Rajbari District Hospital Dhaka Rajbari Rajbari Sadar 100 16 Shariatpur District Hospital Dhaka Shariatpur Shariatpur Sadar 100 17 Bagerhat District Hospital Khulna Bagerhat Bagerhat Sadar 100 18 Chuadanga District Hospital Khulna Chuadanga Chuadanga Sadar 100 19 Jhenaidah District Hospital Khulna Jhenaidah Jhenaidah Sadar 100 20 Narail District Hospital Khulna Narail Narail Sadar 100 21 Satkhira District Hospital Khulna Satkhira Satkhira Sadar 100 22 Netrokona District Hospital Mymensingh Netrakona -

Non-Timber Forest Products and Livelihoods in the Sundarbans

Non-timber Forest Products and Livelihoods in the Sundarbans Fatima Tuz Zohora1 Abstract The Sundarbans is the largest single block of tidal halophytic mangrove forest in the world. The forest lies at the feet of the Ganges and is spread across areas of Bangladesh and West Bengal, India, forming the seaward fringe of the delta. In addition to its scenic beauty, the forest also contains a great variety of natural resources. Non-timber forest products (NTFPs) play an important role in the livelihoods of local people in the Sundarbans. In this paper I investigate the livelihoods and harvesting practices of two groups of resource harvesters, the bauwalis and mouwalis. I argue that because NTFP harvesters in the Sundarbans are extremely poor, and face a variety of natural, social, and financial risks, government policy directed at managing the region's mangrove forest should take into consideration issues of livelihood. I conclude that because the Sundarbans is such a sensitive area in terms of human populations, extreme poverty, endangered species, and natural disasters, co-management for this site must take into account human as well as non-human elements. Finally, I offer several suggestions towards this end. Introduction A biological product that is harvested from a forested area is commonly termed a "non-timber forest product" (NTFP) (Shackleton and Shackleton 2004). The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) defines a non-timber forest product (labeled "non-wood forest product") as "A product of biological origin other than wood derived from forests, other wooded land and trees outside forests" (FAO 2006). For the purpose of this paper, NTFPs are identified as all forest plant and animal products except for timber. -

Rural Development and the Problem of Access: the Case of the Integrated Rural Development Programme

RURAL DEVELOPMENT AND THE PROBLEM OF ACCESS: THE CASE OF THE INTEGRATED RURAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME IN BANGLADESH. Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London By SALIM MOMTAZ B.Sc. (Hons.) (Dhaka); M.Sc. (Dhaka) University College London March, 1990. ProQuest Number: 10609862 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10609862 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT Rural development programmes are normally regarded as necessary for alleviating mass rural poverty in the Developing World, but to be successful they must reach small farmers and the landless. The available evidence suggests that major rural development programme instituted by the Bangladesh Government in the 1960s, the Integrated Rural Development Programme (IRDP), has failed to assist the poorer sections of the rural community to any great extent. Although recently re-designed to provide better access to its services for small farmers and the landless, it will be argued that the main reason for its continuing failure to meet their needs arises from their variable access to land and other private resources which to-gether limit the advantages to be acquired from the goods and services provided under the IRDP. -

Executive Summary

Inception Report Preparation of Development Plan under “Preparation of Development Plan for Fourteen Upazilas” Project- Package-04 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report describes the inception activities of the consultancy work for Package- 04 (Saghata Upazila of Gaibandha District and Sariakandi Upazila & Sonatola Upazila of Bogra District) of the ‘Preparation of Development Plan under Preparation of Development Plan for Fourteen Upazilas’ Project under Urban Development Directorate (UDD) of the Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. The report is being submitted in pursuance of the agreement signed between the client Urban Development Directorate (UDD) and Modern Engineers Planners and Consultants Ltd. (MEPC) on 24th December 2014. The core objective of the project is preparing planning packages to ensure the future growth and development of the project area in a planned and organized way. The current project would emphasize over those activities focusing on all relevant social and physical infrastructure services and facilities including the national level communication network. It would emphasize over the economic development in and around the project area and also livelihood of the local people, who are very much depended on local economic activities. The current project would also emphasize over the change in land category, land use and livelihood pattern. This report is the 2nd footprint followed by Mobilization Report to achieve goal and objectives of the project. The Inception Report describes the inception of project activities -

Ethnobotanical Study of Munshiganj in Shyamnagar Upazilla, Satkhira

AMERICAN-EURASIAN JOURNAL OF SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE ISSN: 1995-0748, EISSN: 1998-1074 2018, volume(12),issue(1):pages(22-29) DOI: 10.22587/aejsa.2018.12.1.4 Published Online inAprilhttp://www.aensiweb.com/AEJSA/ Ethnobotanical Study of Munshiganj in Shyamnagar Upazilla, Satkhira, Bangladesh 1Tama Ray and2Kingson Mondal 1Tama Ray, Co- Founder, Conservation Club, Khulna, Bangladesh. 2Kingson Mondal, Founder, Conservation Club, Khulna, Bangladesh. Received date: 10 January 2018, Accepted date: 28 March 2018, Online date: 4 April 2018 Address For Correspondence: Tama Ray, Khulna University, Forestry and Wood Technology, Khulna- 9208, Khulna , Bangladesh E-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2018 by authors and American-Eurasian Network for Scientific Information. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ABSTRACT Background: Bangladesh is very rich in floral diversification having almost 5000 species; but the thing is that the existence of floral community is now at stake due to diminishing knowledge of the local people about the uses and importance of plant species as the societies are going through a changing lifestyle; as a result, they are showing harsh behavior to the plant population to fulfill their satisfaction. Objective: In our study, we tried to document the species’ availability, composition and diversity of the study area as well as the ethnobotanical knowledge of the people residing there about the uses of plant species in order to transfer that knowledge from generation to generation for helping in the long-term plant species conservation. Results: 44 species under 27 families were cited by the interviewee and 25 species out of 44 have food value which is the highest use value of all categories (Food, Construction, Medicine, Fuelwood and Other). -

Ministry of Food and Disaster Management

Disaster Management Information Centre Disaster Management Bureau (DMB) Ministry of Food and Disaster Management Disaster Management and Relief Bhaban (6th Floor) 92-93 Mohakhali C/A, Dhaka-1212, Bangladesh Phone: +88-02-9890937, Fax: +88-02-9890854 Email:[email protected],H [email protected] Web:http://www.cdmp.org.bd,H www.dmb.gov.bd Emergency Summary of Cyclonic Storm “AILA” Title: Emergency Bangladesh Location: 20°22'N-26°36'N, 87°48'E-92°41'E, Covering From: SAT-30-MAY-2009:1430 Period: To: SUN-31-MAY-2009:1500 Transmission Date/Time: SUN-31-MAY-2009:1630 Prepared by: DMIC, DMB Summary of Cyclonic Storm “AILA” Current Situation Total 14 districts were affected by the cyclone. 147 persons Total Death: 167 reported dead. Many areas of the affected districts were inundated and houses, roads and embankments were People Missed: 0 damaged. Detailed damage information collection is in progress. People Injured: 7,108 Government administration, local elected representatives and Family Affected: 7,34,189 other Non Government organizations are now working in rescue and response in cyclone affected upazilas around the coastal People Affected: 32,19,013 areas. These organization have started their relief and Houses Damaged: 5,41,351 rehabilitation operations immediately just after the cyclone crossed over. Crops Damaged: 3,05,156 acre Local elected representatives and elites are encouraging and providing confidence to the affected people for facing the situation. The Bangladesh army and Coast Guard are trying to establish local communication and still handling the rescue operations. Actions Taken • In a follow up meeting of special meeting of Disaster & Emergency Response (DER) group held in CDMP conference room today decided that the NGO’s/donors will send their responses to DMIC and DER for further assessment by 02 June 2009. -

Diversity of Cropping Patterns and Land Use Practices in Faridpur Region

Bangladesh Rice J. 21 (2) : 157-172, 2017 Diversity of Cropping Patterns and Land Use Practices in Faridpur Region A B M Mostafizur1*, M A U Zaman1, S M Shahidullah1 and M Nasim1 ABSTRACT The development of agriculture sector largely depends on the reliable and comprehensive statistics of the existing cropping patterns, cropping intensity and crop diversity of a particular area, which will provide guideline to policy makers, researchers, extensionists and development workers. The study was conducted over all 29 upazilas of Faridpur region during 2015-16 using pre-tested semi-structured questionnaire with a view to document the existing cropping patterns, cropping intensity and crop diversity of this area. From the present study it was observed that about 43.23% net cropped area (NCA) was covered by only jute based cropping patterns on the other hand deep water ecosystem occupied about 36.72% of the regional NCA. The most dominant cropping pattern Boro−Fallow− Fallow occupied about 24.40% of NCA with its distribution over 28 out of 29. The second largest area, 6.94% of NCA, was covered by Boro-B. Aman cropping pattern, which was spread out over 23 upazilas. In total 141 cropping patterns were identified under this investigation. The highest number of cropping patterns was identified 44 in Faridpur sadar and the lowest was 12 in Kashiani of Gopalganj and Pangsa of Rajbari. The lowest crop diversity index (CDI) was reported 0.448 in Kotalipara followed by 0.606 in Tungipara of Gopalganj. The highest value of CDI was observed 0.981 in Faridpur sadar followed by 0.977 in Madhukhali of Faridpur.