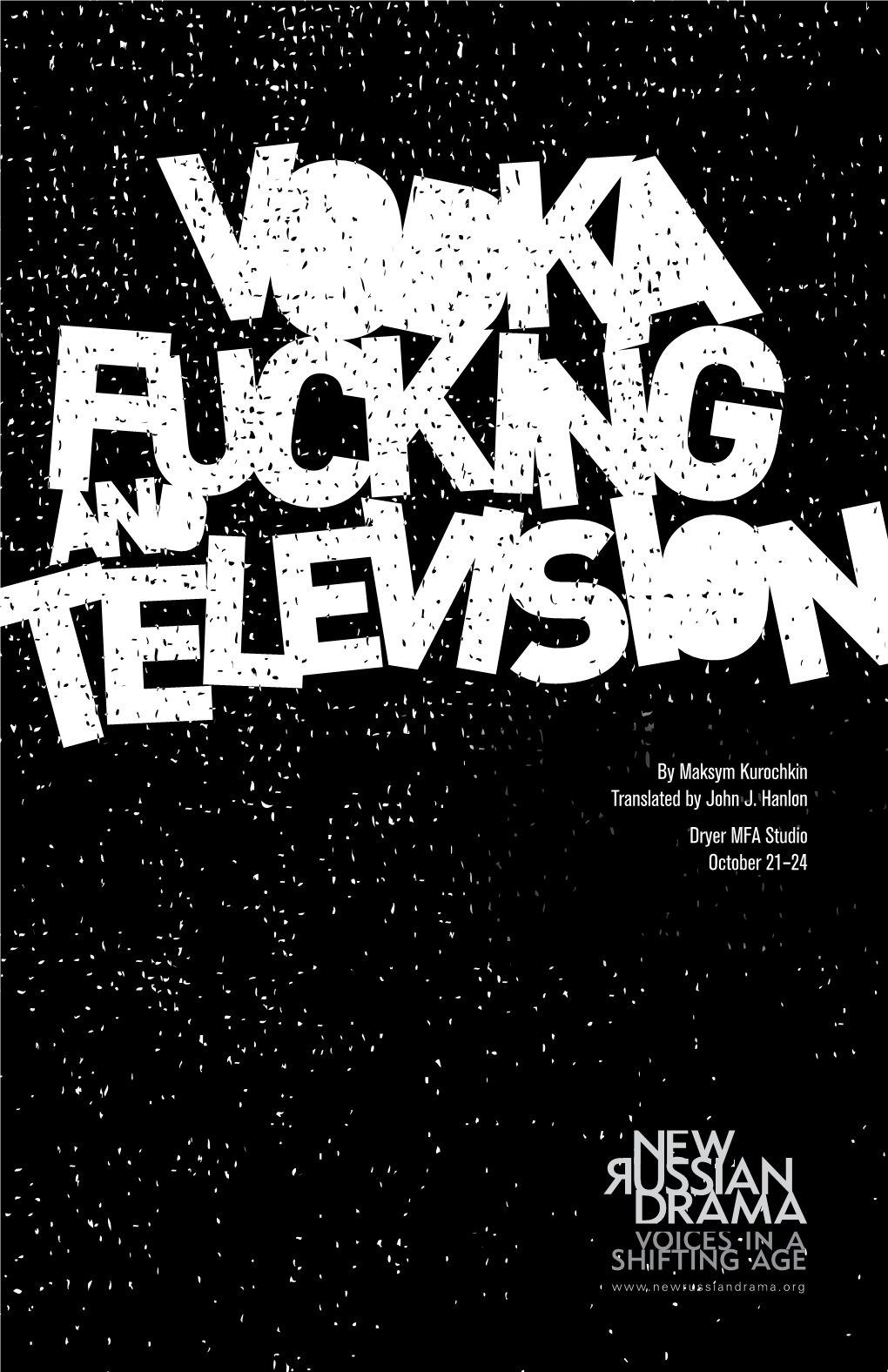

By Maksym Kurochkin Translated by John J. Hanlon Dryer MFA Studio October 21–24

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diss Gradschool Submission

OUTPOST OF FREEDOM: A GERMAN-AMERICAN NETWORK’S CAMPAIGN TO BRING COLD WAR DEMOCRACY TO WEST BERLIN, 1933-72 Scott H. Krause A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Konrad H. Jarausch Christopher R. Browning Klaus W. Larres Susan Dabney Pennybacker Donald M. Reid Benjamin Waterhouse © 2015 Scott H. Krause ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Scott H. Krause: Outpost of Freedom: A German-American Network’s Campaign to bring Cold War Democracy to West Berlin, 1933-66 (under the direction of Konrad H. Jarausch) This study explores Berlin’s sudden transformation from the capital of Nazi Germany to bastion of democracy in the Cold War. This project has unearthed how this remarkable development resulted from a transatlantic campaign by liberal American occupation officials, and returned émigrés, or remigrés, of the Marxist Social Democratic Party (SPD). This informal network derived from members of “Neu Beginnen” in American exile. Concentrated in wartime Manhattan, their identity as German socialists remained remarkably durable despite the Nazi persecution they faced and their often-Jewish background. Through their experiences in New Deal America, these self-professed “revolutionary socialists” came to emphasize “anti- totalitarianism,” making them suspicious of Stalinism. Serving in the OSS, leftists such as Hans Hirschfeld forged friendships with American left-wing liberals. These experiences connected a wider network of remigrés and occupiers by forming an epistemic community in postwar Berlin. They recast Berlin’s ruins as “Outpost of Freedom” in the Cold War. -

Baseball, Rituals, and the American Dream: an Analysis of the Boston

Baseball, Rituals, and the American Dream: An Analysis of the Boston Red Sox’s Response to the Boston Marathon Bombing By © 2019 Benton James Bajorek BA, Arkansas State University, 2015 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Communication Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Chair: Dr. Beth Innocenti Dr. Scott Harris Dr. Robert Rowland Date Defended: 14 January 2019 ii The thesis committee for Benton James Bajorek certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Baseball, Rituals, and the American Dream: An Analysis of the Boston Red Sox’s Response to the Boston Marathon Bombing Chair: Dr. Beth Innocenti Date Approved: 14 January 2019 iii Abstract In April 2013, the Tsarnaev brothers placed two homemade bombs near the finish line of the Boston Marathon. This attack created a need for healing the city’s spirit and the Boston Red Sox played an essential role in the city’s recovery as the team invited victims and first responders to pregame ceremonies throughout the season to participate in ritualistic pregame ceremonies. This thesis examines the Red Sox first home game after the bombing and argues that ritualistic pregame ceremonies craft conditions for performing national citizenship identity by calling upon mythic belief systems to warrant norms of citizenship performance. iv Acknowledgments I did not know what to expect from my first year of graduate school at the University of Kansas. Five years ago, I would never have dreamed of being in the position I’m currently in. -

The Last Hero Free

FREE THE LAST HERO PDF Terry Pratchett,Paul Kidby | 176 pages | 20 Sep 2007 | Orion Publishing Co | 9780575081963 | English | London, United Kingdom The Last Hero (album) - Wikipedia The Last Hero is a The Last Hero fantasy novel by British writer Terry Pratchettthe twenty-seventh book in his Discworld series. The Last Hero was published in in a larger format than the other Discworld novels and illustrated on every The Last Hero by Paul Kidby. A The Last Hero, carried by pointless albatross, arrives for Lord Vetinari from the Agatean Empire. The message explains that the Silver Horde a group of aged barbarians introduced in Interesting TimesThe Last Hero they conquered the Empire, and led by Cohen the Barbariannow the Emperor have set The Last Hero on a quest. The first hero of the Discworld"Fingers" Mazda, stole fire The Last Hero the The Last Hero and gave The Last Hero to mankind analogous to Prometheusand was chained to a rock to be torn open daily by a giant eagle as punishment. As the last heroes remaining on the Disc, the Silver Horde seek to return fire to the gods with interest, in the form of a large sled packed with explosive Agatean Thunder Clay. They plan to blow up the gods at their mountain home, Cori Celesti. With them is a whiny, terrified bard, whom they have kidnapped so that he can write the saga of their quest. Along the way, The Last Hero are joined by Evil Harry Dread the last Dark Lord and Vena the Raven-haired an elderly heroine who has now gone grey. -

Survivor” – How National Identities Are Represented in a Transnational Reality Format

Södertörns högskola | Institutionen för kultur och lärande | Kandidatuppsats 15 hp | Medie- och kommunikationsvetenskap | Vårterminen 2013 A study of the reality game show concept “Survivor” – how national identities are represented in a transnational reality format Av: Anastasia Malko Handledare: Gregory Goldenzwaig 1 Spring semester 2013 Abstract ___________________________________________________________________________ Author: Anastasia Malko Tutor: Gregory Goldenzwaig Title: A study of the reality game show concept “Survivor” – how national identities are represented in a transnational reality format ___________________________________________________________________________ Since TV became the most influential medium globally, the media content followed and as a result, a variety of programmes became international. When it came to entertainment, reality game show Survivor became a pioneer in crossing national borders when the programme’s format was licensed and sold worldwide. The ability of a single reality TV show format to appeal to different nations is remarkable and noteworthy, which consequently makes it an interesting field of research. Therefore, this essay focuses on analysing the narrative structures of the Survivor format productions in Sweden, the USA and Russia in pursuance of revealing representations and reproductions of the nations. It answers the questions about the narrative structures of the programmes, as well as about their common construction, and describes how the national identities are portrayed in a transnational reality game show format. In order to make the study extensive but at the same time significant, a structural narrative analysis with a comparative approach was chosen as a method. The selection was based on the importance of analysing the content of narratives in order to comprehend their illustrations of reality and, among other things, national identities.