Secular Evolution of Asteroid Families: the Role of Ceres

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Corpi Minori Del Sistema Solare

UNIVERSITA' DEGLI STUDI DI BOLOGNA FACOLTA' DI SCIENZE MATEMATICHE, FISICHE E NATURALI Dipartimento di Astronomia Corso di Laurea in Astronomia Materia di Tesi: Astronomia I CORPI MINORI DEL SISTEMA SOLARE Tesi di Laurea di: Relatore: CLAUDIO ELIDORO Chiar.mo Prof. CORRADO BARTOLINI Sessione Autunnale Anno Accademico 1995 - 1996 INDICE INTRODUZIONE 1. UNA VISIONE D'INSIEME 3 2. L'ORIGINE DEL SISTEMA SOLARE 7 3. METODOLOGIE OSSERVATIVE DEI CORPI MINORI 14 PARTE PRIMA: GLI ASTEROIDI 1. NOTA STORICA 17 2. ORIGINE DEGLI ASTEROIDI 19 3. IL RUOLO DEGLI IMPATTI 25 4. FAMIGLIE DINAMICHE 31 5. CLASSIFICAZIONE 39 6. "INCONTRI RAVVICINATI" 48 951 GASPRA 49 243 IDA 52 433 EROS ED I N.E.A. 54 4179 TOUTATIS 61 7. LA TERRA COME BERSAGLIO 65 PARTE SECONDA: LE COMETE 1. NOTA STORICA 81 2. ORIGINE ED EVOLUZIONE 2.1 LA NUBE DI OORT E LA FASCIA DI KUIPER 82 2.2 LE COMETE A CORTO PERIODO 88 2.3 FASI EVOLUTIVE FINALI 94 3. MORFOLOGIA E FENOMENI FISICI CONNESSI 3.1 IL MODELLO DI WHIPPLE 100 3.2 IL NUCLEO 107 3.3 LA CHIOMA 111 3.4 LA CODA 116 PARTE TERZA: KUIPER-BELT OBJECTS 1. NOTA STORICA 119 2. IL SISTEMA PLUTONE - CARONTE 124 3. CHIRONE ED I CENTAURI 128 4. UNA POPOLAZIONE TUTTA DA SCOPRIRE 134 BIBLIOGRAFIA 139 - 2 - INTRODUZIONE 1. UNA VISIONE D'INSIEME Scorrendo le tappe fondamentali della Storia dell'Astronomia, appare evidente come il quadro complessivo del Sistema Solare si sia gradualmente modificato e ampliato man mano che la ricerca e la tecnologia mettevano a disposizione strumenti di indagine più adeguati. -

The Recent Breakup of an Asteroid in the Main-Belt Region

letters to nature .............................................................. (see Methods section). The recent breakup of an asteroid in The orbital distribution of the 39-body cluster is diagonally shaped in (a P, e P), and appears to fit inside one of the similarly the main-belt region shaped ‘equivelocity’ ellipses shown in Fig. 1. To create these ellipses, we launched test bodies isotropically from the centre of David Nesvorny´, William F. Bottke Jr, Luke Dones & Harold F. Levison the cluster (presumably the impact site) at a selected velocity impulse dV. Using Gauss’s equations (see, for example, ref. 14), Southwest Research Institute, 1050 Walnut St, Suite 426, Boulder, Colorado we then computed the change in their proper elements (da P, de P, 80302, USA diP). To determine the size, shape and orientation of the ellipses, we ............................................................................................................................................................................. experimented with various values of Vmax, the maximum velocity The present population of asteroids in the main belt is largely the 1,2 among our test bodies, the true anomaly f of the parent body (that result of many past collisions . Ideally, the asteroid fragments is, the angle between the parent body’s location and the perihelion resulting from each impact event could help us understand the of its orbit) and the parent body’s perihelion argument q at the large-scale collisions that shaped the planets during early instant of the impact (that is, the angle between the perihelion and epochs3–5. Most known asteroid fragment families, however, are the ascending node). very old and have therefore undergone significant collisional and We found that ellipsoids having V < 15 m s21, dynamical evolution since their formation6. -

The Minor Planet Bulletin

THE MINOR PLANET BULLETIN OF THE MINOR PLANETS SECTION OF THE BULLETIN ASSOCIATION OF LUNAR AND PLANETARY OBSERVERS VOLUME 36, NUMBER 3, A.D. 2009 JULY-SEPTEMBER 77. PHOTOMETRIC MEASUREMENTS OF 343 OSTARA Our data can be obtained from http://www.uwec.edu/physics/ AND OTHER ASTEROIDS AT HOBBS OBSERVATORY asteroid/. Lyle Ford, George Stecher, Kayla Lorenzen, and Cole Cook Acknowledgements Department of Physics and Astronomy University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire We thank the Theodore Dunham Fund for Astrophysics, the Eau Claire, WI 54702-4004 National Science Foundation (award number 0519006), the [email protected] University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Office of Research and Sponsored Programs, and the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire (Received: 2009 Feb 11) Blugold Fellow and McNair programs for financial support. References We observed 343 Ostara on 2008 October 4 and obtained R and V standard magnitudes. The period was Binzel, R.P. (1987). “A Photoelectric Survey of 130 Asteroids”, found to be significantly greater than the previously Icarus 72, 135-208. reported value of 6.42 hours. Measurements of 2660 Wasserman and (17010) 1999 CQ72 made on 2008 Stecher, G.J., Ford, L.A., and Elbert, J.D. (1999). “Equipping a March 25 are also reported. 0.6 Meter Alt-Azimuth Telescope for Photometry”, IAPPP Comm, 76, 68-74. We made R band and V band photometric measurements of 343 Warner, B.D. (2006). A Practical Guide to Lightcurve Photometry Ostara on 2008 October 4 using the 0.6 m “Air Force” Telescope and Analysis. Springer, New York, NY. located at Hobbs Observatory (MPC code 750) near Fall Creek, Wisconsin. -

Asteroid Family Ages. 2015. Icarus 257, 275-289

Icarus 257 (2015) 275–289 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus Asteroid family ages ⇑ Federica Spoto a,c, , Andrea Milani a, Zoran Knezˇevic´ b a Dipartimento di Matematica, Università di Pisa, Largo Pontecorvo 5, 56127 Pisa, Italy b Astronomical Observatory, Volgina 7, 11060 Belgrade 38, Serbia c SpaceDyS srl, Via Mario Giuntini 63, 56023 Navacchio di Cascina, Italy article info abstract Article history: A new family classification, based on a catalog of proper elements with 384,000 numbered asteroids Received 6 December 2014 and on new methods is available. For the 45 dynamical families with >250 members identified in this Revised 27 April 2015 classification, we present an attempt to obtain statistically significant ages: we succeeded in computing Accepted 30 April 2015 ages for 37 collisional families. Available online 14 May 2015 We used a rigorous method, including a least squares fit of the two sides of a V-shape plot in the proper semimajor axis, inverse diameter plane to determine the corresponding slopes, an advanced error model Keywords: for the uncertainties of asteroid diameters, an iterative outlier rejection scheme and quality control. The Asteroids best available Yarkovsky measurement was used to estimate a calibration of the Yarkovsky effect for each Asteroids, dynamics Impact processes family. The results are presented separately for the families originated in fragmentation or cratering events, for the young, compact families and for the truncated, one-sided families. For all the computed ages the corresponding uncertainties are provided, and the results are discussed and compared with the literature. The ages of several families have been estimated for the first time, in other cases the accu- racy has been improved. -

The Solar System

5 The Solar System R. Lynne Jones, Steven R. Chesley, Paul A. Abell, Michael E. Brown, Josef Durech,ˇ Yanga R. Fern´andez,Alan W. Harris, Matt J. Holman, Zeljkoˇ Ivezi´c,R. Jedicke, Mikko Kaasalainen, Nathan A. Kaib, Zoran Kneˇzevi´c,Andrea Milani, Alex Parker, Stephen T. Ridgway, David E. Trilling, Bojan Vrˇsnak LSST will provide huge advances in our knowledge of millions of astronomical objects “close to home’”– the small bodies in our Solar System. Previous studies of these small bodies have led to dramatic changes in our understanding of the process of planet formation and evolution, and the relationship between our Solar System and other systems. Beyond providing asteroid targets for space missions or igniting popular interest in observing a new comet or learning about a new distant icy dwarf planet, these small bodies also serve as large populations of “test particles,” recording the dynamical history of the giant planets, revealing the nature of the Solar System impactor population over time, and illustrating the size distributions of planetesimals, which were the building blocks of planets. In this chapter, a brief introduction to the different populations of small bodies in the Solar System (§ 5.1) is followed by a summary of the number of objects of each population that LSST is expected to find (§ 5.2). Some of the Solar System science that LSST will address is presented through the rest of the chapter, starting with the insights into planetary formation and evolution gained through the small body population orbital distributions (§ 5.3). The effects of collisional evolution in the Main Belt and Kuiper Belt are discussed in the next two sections, along with the implications for the determination of the size distribution in the Main Belt (§ 5.4) and possibilities for identifying wide binaries and understanding the environment in the early outer Solar System in § 5.5. -

Asteroid Family Identification 613

Bendjoya and Zappalà: Asteroid Family Identification 613 Asteroid Family Identification Ph. Bendjoya University of Nice V. Zappalà Astronomical Observatory of Torino Asteroid families have long been known to exist, although only recently has the availability of new reliable statistical techniques made it possible to identify a number of very “robust” groupings. These results have laid the foundation for modern physical studies of families, thought to be the direct result of energetic collisional events. A short summary of the current state of affairs in the field of family identification is given, including a list of the most reliable families currently known. Some likely future developments are also discussed. 1. INTRODUCTION calibrate new identification methods. According to the origi- nal papers published in the literature, Brouwer (1951) used The term “asteroid families” is historically linked to the a fairly subjective criterion to subdivide the Flora family name of the Japanese researcher Kiyotsugu Hirayama, who delineated by Hirayama. Arnold (1969) assumed that the was the first to use the concept of orbital proper elements to asteroids are dispersed in the proper-element space in a identify groupings of asteroids characterized by nearly iden- Poisson distribution. Lindblad and Southworth (1971) cali- tical orbits (Hirayama, 1918, 1928, 1933). In interpreting brated their method in such a way as to find good agree- these results, Hirayama made the hypothesis that such a ment with Brouwer’s results. Carusi and Massaro (1978) proximity could not be due to chance and proposed a com- adjusted their method in order to again find the classical mon origin for the members of these groupings. -

On the Astrid Asteroid Family

MNRAS 461, 1605–1613 (2016) doi:10.1093/mnras/stw1445 Advance Access publication 2016 June 16 On the Astrid asteroid family Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-abstract/461/2/1605/2608554 by Universidade Estadual Paulista J�lio de Mesquita Filho user on 29 May 2019 V. Carruba‹ UNESP, Univ. Estadual Paulista, Grupo de dinamicaˆ Orbital e Planetologia, 12516-410 Guaratingueta,´ SP, Brazil Accepted 2016 June 14. Received 2016 June 10; in original form 2016 May 2 ABSTRACT Among asteroid families, the Astrid family is peculiar because of its unusual inclination distribution. Objects at a 2.764 au are quite dispersed in this orbital element, giving the family a ‘crab-like’ appearance. Recent works showed that this feature is caused by the interaction of the family with the s − sC nodal secular resonance with Ceres, that spreads the inclination of asteroids near its separatrix. As a consequence, the currently observed distribution of the vW component of terminal ejection velocities obtained from inverting Gauss equation is quite leptokurtic, since this parameter mostly depends on the asteroids inclination. The peculiar orbital configuration of the Astrid family can be used to set constraints on key parameters describing the strength of the Yarkovsky force, such as the bulk and surface density and the thermal conductivity of surface material. By simulating various fictitious families with different values of these parameters, and by demanding that the current value of the kurtosis of the distribution in vW be reached over the estimated lifetime of the family, we obtained that the thermal conductivity of Astrid family members should be 0.001 W m−1 K−1, and that the surface and bulk density should be higher than 1000 kg m−3. -

Size–Frequency Distributions of Fragments from SPH/N-Body Simulations of Asteroid Impacts: Comparison with Observed Asteroid Families

Icarus 186 (2007) 498–516 www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus Size–frequency distributions of fragments from SPH/N-body simulations of asteroid impacts: Comparison with observed asteroid families Daniel D. Durda a,∗, William F. Bottke Jr. a, David Nesvorný a, Brian L. Enke a, William J. Merline a, Erik Asphaug b, Derek C. Richardson c a Southwest Research Institute, 1050 Walnut Street, Suite 400, Boulder, CO 80302, USA b Earth Sciences Department, University of California Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA c Department of Astronomy, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA Received 12 May 2006; revised 1 September 2006 Available online 28 November 2006 Abstract We investigate the morphology of size–frequency distributions (SFDs) resulting from impacts into 100-km-diameter parent asteroids, repre- sented by a suite of 161 SPH/N-body simulations conducted to study asteroid satellite formation [Durda, D.D., Bottke, W.F., Enke, B.L., Merline, W.J., Asphaug, E., Richardson, D.C., Leinhardt, Z.M., 2004. Icarus 170, 243–257]. The spherical basalt projectiles range in diameter from 10 to 46 km (in equally spaced mass increments in logarithmic space, covering six discrete sizes), impact speeds range from 2.5 to 7 km/s (generally in ◦ ◦ ◦ 1km/s increments), and impact angles range from 15 to 75 (nearly head-on to very oblique) in 15 increments. These modeled SFD morpholo- gies match very well the observed SFDs of many known asteroid families. We use these modeled SFDs to scale to targets both larger and smaller than 100 km in order to gain insights into the circumstances of the impacts that formed these families. -

Origin of the Near-Earth Asteroid Phaethon and the Geminids Meteor Shower

University of Central Florida STARS Faculty Bibliography 2010s Faculty Bibliography 1-1-2010 Origin of the near-Earth asteroid Phaethon and the Geminids meteor shower J. de León H. Campins University of Central Florida K. Tsiganis A. Morbidelli J. Licandro Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/facultybib2010 University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Bibliography at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Bibliography 2010s by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation de León, J.; Campins, H.; Tsiganis, K.; Morbidelli, A.; and Licandro, J., "Origin of the near-Earth asteroid Phaethon and the Geminids meteor shower" (2010). Faculty Bibliography 2010s. 92. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/facultybib2010/92 A&A 513, A26 (2010) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/200913609 & c ESO 2010 Astrophysics Origin of the near-Earth asteroid Phaethon and the Geminids meteor shower J. de León1,H.Campins2,K.Tsiganis3, A. Morbidelli4, and J. Licandro5,6 1 Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía-CSIC, Camino Bajo de Huétor 50, 18008 Granada, Spain e-mail: [email protected] 2 University of Central Florida, PO Box 162385, Orlando, FL 32816.2385, USA e-mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Physics, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 54 124 Thessaloniki, Greece 4 Departement Casiopée: Universite de Nice - Sophia Antipolis, Observatoire de la Cˆote d’Azur, CNRS 4, 06304 Nice, France 5 Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC), C/Vía Láctea s/n, 38205 La Laguna, Spain 6 Department of Astrophysics, University of La Laguna, 38205 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain Received 5 November 2009 / Accepted 26 January 2010 ABSTRACT Aims. -

Widespread Water Among Primitive Asteroid Families: New Insights from the Main Belt Comets

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 13, EPSC-DPS2019-892-1, 2019 EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2019 c Author(s) 2019. CC Attribution 4.0 license. Widespread water among primitive asteroid families: new insights from the main belt comets Bojan Novakovic´ (1) and Henry Hsieh (2,3) (1) University of Belgrade, Serbia, (2) Planetary Science Institute, USA, (3) Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Taiwan, ([email protected]) Abstract The obtained results are summarized in Table 1. For the first time we found active asteroids associated to We present new results regarding the association of the Pallas and Luthera families, namely P/2017 S8 and main belt comets to asteroid families. We find three P/2019 A7, respectively. new firm links, and three potential associations. These results further strengthen the link between the main Table 1: A list of asteroid family associations of newly belt comets and compositionally primitive asteroid discovered main belt comet candidates. families. MBC candidate Family 1. Introduction P/2016 P1 (PANSTARRS) Euphrosyne? P/2017 S8 (PANSTARRS) Pallas Main belt comets (MBCs) are a subgroup of active as- P/2017 S5 (PANSTARRS) Theobalda teroids, which exhibit visible mass loss activity yet P/2017 S9 (PANSTARRS) Theobalda? are dynamically asteroidal, for which it is believed P/2019 A3 (PANSTARRS) Theobalda? that observed activity is driven by the sublimation of P/2019 A4 (PANSTARRS) None? volatile ices [1, 2]. Our recent work has demonstrated P/2019 A7 (PANSTARRS) Luthera that all MBCs associated to collisional families be- P/2019 A8 (PANSTARRS) None? long to families with primitive taxonomic classifica- tions [3]. -

An Automatic Approach to Exclude Interlopers from Asteroid Families

MNRAS 470, 576–591 (2017) doi:10.1093/mnras/stx1273 Advance Access publication 2017 May 23 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-abstract/doi/10.1093/mnras/stx1273/3850232 by Universidade Estadual Paulista J�lio de Mesquita Filho user on 19 August 2019 An automatic approach to exclude interlopers from asteroid families Viktor Radovic,´ 1‹ Bojan Novakovic,´ 1 Valerio Carruba2 and Dusanˇ Marcetaˇ 1 1Department of Astronomy, Faculty of Mathematics, University of Belgrade, Studentski trg 16, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia 2UNESP, Univ. Estadual Paulista, Grupo de dinamica Orbital e Planetologia, Guaratinguet, SP 12516-410, Brazil Accepted 2017 May 19. Received 2017 May 19; in original form 2017 March 21 ABSTRACT Asteroid families are a valuable source of information to many asteroid-related researches, assuming a reliable list of their members could be obtained. However, as the number of known asteroids increases fast it becomes more and more difficult to obtain a robust list of members of an asteroid family. Here, we are proposing a new approach to deal with the problem, based on the well-known hierarchical clustering method. An additional step in the whole procedure is introduced in order to reduce a so-called chaining effect. The main idea is to prevent chaining through an already identified interloper. We show that in this way a number of potential interlopers among family members is significantly reduced. Moreover, we developed an automatic online-based portal to apply this procedure, i.e. to generate a list of family members as well as a list of potential interlopers. The Asteroid Families Portal is freely available to all interested researchers. -

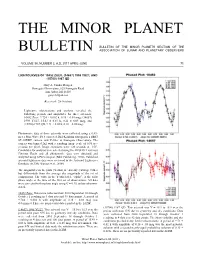

The Minor Planet Bulletin

THE MINOR PLANET BULLETIN OF THE MINOR PLANETS SECTION OF THE BULLETIN ASSOCIATION OF LUNAR AND PLANETARY OBSERVERS VOLUME 38, NUMBER 2, A.D. 2011 APRIL-JUNE 71. LIGHTCURVES OF 10452 ZUEV, (14657) 1998 YU27, AND (15700) 1987 QD Gary A. Vander Haagen Stonegate Observatory, 825 Stonegate Road Ann Arbor, MI 48103 [email protected] (Received: 28 October) Lightcurve observations and analysis revealed the following periods and amplitudes for three asteroids: 10452 Zuev, 9.724 ± 0.002 h, 0.38 ± 0.03 mag; (14657) 1998 YU27, 15.43 ± 0.03 h, 0.21 ± 0.05 mag; and (15700) 1987 QD, 9.71 ± 0.02 h, 0.16 ± 0.05 mag. Photometric data of three asteroids were collected using a 0.43- meter PlaneWave f/6.8 corrected Dall-Kirkham astrograph, a SBIG ST-10XME camera, and V-filter at Stonegate Observatory. The camera was binned 2x2 with a resulting image scale of 0.95 arc- seconds per pixel. Image exposures were 120 seconds at –15C. Candidates for analysis were selected using the MPO2011 Asteroid Viewing Guide and all photometric data were obtained and analyzed using MPO Canopus (Bdw Publishing, 2010). Published asteroid lightcurve data were reviewed in the Asteroid Lightcurve Database (LCDB; Warner et al., 2009). The magnitudes in the plots (Y-axis) are not sky (catalog) values but differentials from the average sky magnitude of the set of comparisons. The value in the Y-axis label, “alpha”, is the solar phase angle at the time of the first set of observations. All data were corrected to this phase angle using G = 0.15, unless otherwise stated.