From-Glasgow-To-Saturn-45-1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

David Shrigley

NEW DRAWINGS — DAVID SHRIGLEY Thursday, November 2 – Friday, December 22, 2017 Venue: Yumiko Chiba Associates viewing room Shinjuku Park Grace Shinjuku Bldg. #206, 4-32-6 Nishi-Shinjuku, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-0023 Gallery Hours: 12:00 – 19:00 *Closed on Sundays, Mondays, and national holidays Copyright David Shrigley. Courtesy of David Shrigley and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London. Opening Reception: Thursday, November 2, 2017, 17:00 – 19:00 Venue: Yumiko Chiba Associates viewing room shinjuku Talk Event: Tuesday, October 31, 2017, 18:00 – 20:00 (The door opens at 17:30.) Venue: The Lecture Hall in the Central Building in the Ueno Campus of Tokyo University of the Arts Speakers: David Shrigley and Ken Kagami Moderator: Kenjin Miwa (Curator of The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo) *Consecutive interpretation available during the session. Admission: Free Seating Capacity: 180 (Served on a first-come-first-served basis, reservation not required.) In Association With: British Council Support: MITO ARTS FOUNDATION, Tokyo University of the Arts Photography Center, Stephen Friedman Gallery (London) Yumiko Chiba Associates viewing room shinjuku is pleased to present New Drawings, a solo show of David Shrigley from Thursday, November 2, 2017. Born in Macclesfield in Northern England in 1968, David Shrigley graduated from the Glasgow School of Art, Scotland's only public self-governing art school. He is currently based in London, and is actively engaged in various projects there. In 2012, while still in his mid-career, David Shrigley had his retrospective show titled Brain Activity held at Hayward Gallery in London, which led him to be nominated for the renowned Turner Prize awarded to artists living in England in 2013. -

Press Bulletin

deSingel,el, Antwerpp internationaonal design conferenceonference 22-23/10/09 integrated2009.com Press bulletin Integrated2009, international design conference, Sint Lucas Antwerp/deSingel 22/23 October 2009 Integrated2009 is a biannual international design conference, organised by Sint Lucas Antwerpen that will take place in deSingel Antwerp on Thursday 22 & Friday 23 October 2009. The conference will focus on the fascinating crossover between contemporary graphic design, illustra- tion, typography, new media & art and will offer a unique interaction between ideas, thoughts and expectations for the near future. With very important speakers such as: Stefan Sagmeister, Adbusters, Karlssonwilker, Kesselskramer, Storm Thorgerson, John L. Walters, David Shrigley, Mevis & Van Deursen, Annelys de Vet etc. Professor Jean Paul Van Bendegem (VUB) will welcome the audience during his opening speech. In this press file, you will find the extented concept memo, the different biographies and a limited portfolio of the main speakers of this conference. Please surf to our website www.integrated2009.com to obtain further information about the program and the registration formalities. In the mean time, the conference is sold out. About 1.000 participants are expected! If you would like to obtain a ticket or high resolution picture files, please mail to [email protected]. We are looking forward meeting you there. Dearest regards. Hugo Puttaert Professor, conference responsible +32 (0)475 42 12 62 KDG - SINT LUCAS ANTWERPEN, SINT-JOZEFSTRAAT 35, B-2018 ANTWERPEN, T +32 (0)3 223 69 70, F +32 (0)3 223 69 89, [email protected] www.sintlucasantwerpen.be 1 deSingel,el, Antwerpp internationaonal design conferenceonference 22-23/10/09 integrated2009.com THU 22/10 FRI 23/10 Lectures will take 40 to 60 minutes and start at the time as mentioned. -

Auction-2020-Catalogue-28Feb.Pdf

3 Inspired food, beautiful parties Proudly supporting Terrence Higgins Trust for over 10 years [email protected] 020 7627 1220 4 WELCOME TO THE AUCTION 2020 THANK YOU Terrence Higgins Trust would like to thank The Auction 2020 Committee for their support – without them tonight would not be possible. We are also incredibly grateful to our event supporters and Lot donors who have generously contributed to the success of The Auction 2020. THE AUCTION 2020 COMMITTEE THE AUCTION 2020 TEAM AT Inspired food, TERRENCE HIGGINS TRUST n Adnan Abbasi n Tom Best EVENT PRODUCTION beautiful parties n Diarmuid Buckley n Sarah Gibling (Project Manager) n Aaron Carty n Bryony McFarland n Fabio Ciquera n Alastair Miller n Michele Codoni n Emily Robinson n Lal Dalamal n Natalie Stephens-Sleigh n Glen Donovan n Iyabo Oba n Nicholas Faulkner n Alco Tippersma n Kieran Fox n Luke Buckingham Proudly supporting Terrence Higgins Trust n Lilly Grimaldi n Alexander Zylko n Garth Heron for over 10 years n Jeff Holland CATALOGUE PRODUCTION n Keith Iddins n Andie Dyer (Project Manager) n Renée Jamieson n Kate Ellis (Editor) n Will Jenkins n Paul Bowen (Designer) n Rob Kendall n Baldassare La Rizza Additional photography supplied by James Basire. n Shannon Leeman n Howard Malin The Auction would not be possible without the continued, fabulous generosity of Christie’s and n Owen Meredith the magnificent Lot donations made by so many n Krishna Omkar companies, artists, designers and individuals. n Trevor Pickett Thank you. n Phillip Plesner n Patrick Saich We would also like to thank William Norris & n Ralph Segreti Company for their delicious catering and continued n Robert Tateossian dedication, and Tateossian for generously supporting the Box of Delights. -

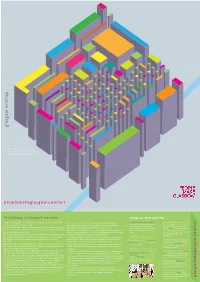

Glasgow Artmap Glasgow

glasgow artmap glasgow Based on Glasgow’s City Centre grid the Iconic ARTMAP goes 3D to celebrate the Turner Prize - with a dash of colour! peoplemakeglasgow.com/art The Pathway to Glasgow’s art scene keep an eye out for . The story of Glasgow’s contemporary art success begins at a time in its relatively The effect of two world wars on Glasgow’s economy dampened the Vincent van Gogh’s portrait of art dealer, Head to Tontine Lane in the heart of the Alexander Reid hangs in Kelvingrove Art Merchant City where you will find one of recent past when the city was booming. pioneering spirit of artists. The city continued to produce outstanding Gallery. The building on West George the most secretive works of public art in The Victorian merchants who made Glasgow flourish appreciated good design. From painters but it was not easy to make a living solely from art. Street in which Reid operated his Glasgow Glasgow. Empire, the cinema-sign artwork the 1890s, creations by local architects such as Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson and John By the late 1950s, fed up with a lack of commercial galleries to take them on, a gallery has now reopened as The Leiper of home-grown Turner Prize winner Burnet, sprung up all around the city. group of art school graduates set up The Young Glasgow Group. They counted Gallery. Douglas Gordon flickers to illuminate the The merchants liked to decorate their mansions with fine art so institutions such as among their number the writer and artist, Alasdair Gray. surrounding industrial buildings and factories. -

David Shrigley

David Shrigley (Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire) Born: 1968, Macclesfield, UK Lives and works in Brighton, England Education 1988-91 Glasgow School of Art, BA Fine Art, Glasgow, Scotland Solo and Two-Person Exhibitions (selected) 2021–2022 David Shrigley, Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, England David Shrigley: A Retrospective, K Museum of Contemporary Art, Seoul, South Korea (catalogue) 2021 Gyre, Tokyo, Japan (two-person, with Teppei Kaneuji) 2020–2021 CLARITY: IT IS VERY IMPORTANT, Yumiko Chiba Associates, Tokyo, Japan 2020 Do Not Touch the Worms, Copenhagen Contemporary, Denmark Fond Memories of Giant Bug, Jiri Svestka Gallery, Prague, Czech Republic 2019 Kindness: Prints & Drawings by David Shrigley, Newstead Abbey Historic House & Gardens, Nottinghamshire, England Do it (do not do it), Museo de arte Carrillo Gil, Mexico City, Mexico David Shrigley: To Be of Use, Art Omi, Ghent, New York, USA Exhibition of Inflatable Swan Things and Other Things, Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen, Denmark Fluff War, Anton Kern Gallery, New York, USA David Shrigley, Two Rooms, Auckland, New Zealand 2018–2019 Exhibition of Inflatable Swan Things, Spritmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden David Shrigley, Sketch, London, England 2018 David Shrigley: Life Model II, Fabrica, Brighton, England David Shrigley: Laughterhouse, Deste Foundation Project Space, Hydra, Athens, Greece Lose Your Mind, Power Station of Art & Design, Shanghai, China 2017 New Drawings, Yumiko Chiba Associates, Tokyo, Japan Skip Gallery, London, England Hall Art Foundation, Reading, VT Problem Guitars, Anton Kern Gallery, Independent New York, USA 2016–2017 Lose Your Mind, British Council, Instituto Cultural Cabañas, Guadalajara, Mexico touring to MAC, Santiago, Chile, Storage by Hyundai Card, Seoul and Art Tower Mito, Japan 25—28 Old Burlington Street London W1S 3AN T +44 (0)20 7494 1434 stephenfriedman.com 2016-2018 Really Good, The Fourth Plinth, Trafalgar Square, London, England 2016 Memorial, Public Art Fund commission, Doris C. -

Biography Website Format

IAN DAVENPORT BIOGRAPHY 1966 Born 8 July, Kent 1984–85 Northwich College of Art and Design, Cheshire 1985–88 Goldsmiths College of Art, London (B.A. Fine Art) 1991 Nominated for Turner Prize 1996–97 Commissioned to create a site-specific installation for Banque BNP Paribas in London 1999 Prizewinner John Moores Liverpool Exhibition 21 2000 Prizewinner Premio del Golfo, La Spezia, Italy 2002 Awarded first prize Prospects (sponsored by Pizza Express), Essor Project Space, London 2003 Makes a wall painting for the Groucho Club, London 2004 Commissioned by the Contemporary Art Society to make a wall painting for the Institute of Mathematics and Statistics at Warwick University, titled Everything Retrospective opens at Ikon, Birmingham, in September Marries Sue Arrowsmith 2006 Poured Lines: Southwark Street, a 3 by 48 metre painting commissioned by Southwark Council and Land Securities as part of a regeneration project in Bankside, London, installed under Western Bridge, Southwark Street, London Commissioned to design a limited edition cover for the September issue of Wallpaper 2007 Commissioned by The New York Times Magazine to create an American Flag based on an environmentally friendly theme along with seven other artists to be featured in their 15 April issue. Ian’s work is reproduced on the title page of the article ‘The Power of Green’. Completed Poured Lines: QUBE Building, a 2.85 by 15 metre painting, commissioned by Derwent London for the QUBE Building, Fitzrovia, London 2010 Commissoned by Wallpaper Magazine to produce a mural with -

David Shrigley

DAVID SHRIGLEY Born in 1968, Macclesfield, UK Lives and works in Glasgow, Scotland SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2013 Signs, Anton Kern Gallery, New York, NY 2012 Animations, Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen, Denmark Bradford 1 Gallery, Bradford, UK HOW ARE YOU FEELING?, Cornerhouse Gallery, Manchester, UK High Line Art (commissioned billboard), New York, NY Arms Fayre, Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, UK Brain Activity, Hayward Gallery, London, UK Brain Activity, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, CA Beginning, Middle and End, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, Denmark Mumbai Art Room, Pipewala Building, Mumbai, India 2011 Yvon Lambert, Paris, France Animate, Turku Art Museum, Turku, Finland David Shrigley, BQ Berlin, Berlin, Germany 2010 Insects, Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen, Denmark I am not very good at drawing women, so I end up drawing a lot of deformed men, M-Museum Leuven, Leuven, Belgium Anton Kern Gallery, New York, NY David Shrigley at Kelvingrove, Kelvingrove Art Gallery & Museum, Glasgow, Scotland 2009 Bergen Kunsthall, Bergen, Norway Mainz Kunsthalle, Mainz, Germany Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen, Denmark 2008 BQ, Cologne Anton Kern Gallery, New York Francesca Pia, Zurich Monotypes, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany Corroborative Paintings (with Jonathan Monk), Galeria Estrany, Barcelona David Shrigley, BALTIC, Gateshead, England 2007 WWW.SAATCHIGALLERY.COM DAVID SHRIGLEY Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen, Denmark Malmo Konsthall, Malmo Yvon Lambert, Paris, France 2006 Niels Borch Jensen Gallery, Berlin -

David Shrigley CLARITY

David Shrigley CLARITY: IT IS VERY IMPORTANT Saturday, November 28, 2020 - Saturday, January 30, 2021 (The exhibition will be closed from Sunday, December 27, 2020 to Monday, January 11, 2021.) Venue: Yumiko Chiba Associates viewing room shinjuku #206, Park Grace Shinjuku Bldg., 4-32-6 Nishi-Shinjuku, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-0023 Gallery Hours: 12:00 - 18:00 Closed on Sundays, Mondays, and national holidays *Opening reception will not be held. Special Talk: Speakers: David Shrigley x Kenjin Miwa (curator, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo) *Consecutive interpretation available. Online Event: NADiff a/p/a/r/t on zoom/webinar Date/time: From 20:00 to 21:30, Saturday, December 12, 2020 Fee: ¥1,100 (Tax included) For booking, visit NADiff website below: https://peatix.com/event/1708317/view David Shrigley, Untitled, 2019 ⒸDavid Shrigley, Courtesy of Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and Yumiko Chiba Associates, Tokyo *Please be aware that the above event will not take place on the first day of the exhibition. [Request prior to admission] *We would like to ask visitors to refrain from visiting the gallery if visitors have symptoms such as a fever, headache, cough, shortness of breath or difficulty breathing, fatigue, loss of taste or smell. *We request visitors to wear masks. Visitors are also asked to sanitize hands, and non-contact temperature readings upon visiting will be taken before entering the gallery. *Visitors contact information will be asked as part of contact-tracing measures. *We kindly ask visitors not to visit in a large group. *Limited numbers of visitors will be allowed at one time to avoid crowdedness. -

Malcom Middleton GB

Malcom Middleton GB Lu 7 sept 20h « Middleton incarne le genre d’ami cabossé avec qui l’on rêverait de vider un bar pour se réchauffer » : cette image du mu- sicien écossais, sortie des pages de l’incontournable revue indie L’Abri Magic en 2009, parle d’elle-même. Mais dix ans après la sépara- tion de son groupe, les mythiques Arab Strap, le « clown triste » Ouverture des portes à 19h30 du rock britannique a su rebondir sans jamais lâcher sa plume in- comparable ; en attestent ses nouveaux projets succédant à cinq En collaboration avec L’Abri albums acoustiques en solo. Si l’année passée il collaborait sur un album écrit et illustré à quatre mains avec son compatriote David Le 7 sept à 18h à la Shrigley, artiste plasticien non seulement (re)connu pour son hu- Bibliothèque de la Cité, mour absurde mais aussi pour la beauté de ses dessins, Malcolm rencontre avec Malcolm Middleton a récemment rebranché les guitares électriques avec Middleton sous le titre Music sa nouvelle et passionnante formation, Human Don’t Be Angry. Un and Word. second souffle artistique lumineux ! Rencontre en partenariat avec les malcolmmiddleton.co.uk Bibliothèques Municipales © DR Dossier de presse 1 La Bâtie 2015 Malcom Middleton Malcolm Middleton is a guitarist and songwriter who shot to relative success in the late 1990s as one half of the Scottish alternative rock band Arab Strap. Over the course of 10 years they released 6 studio albums and toured most of the toilet-sized venues of the world, even playing some mid-sized bathrooms latterly during their well-in-advance-announced farewell tour in the winter of 2006. -

David Shrigley

David Shrigley David Shrigley was born in 1968 in Macclesfield, UK. He is now based in Brighton, England. David Shrigley is best known for his distinctive drawing style and works that make satirical comments on everyday situations and human interactions. His quick-witted drawings and hand-rendered texts are typically deadpan in their humour and reveal chance utterings like snippets of over-heard conversations. Reoccurring themes and thoughts pervade his story telling capturing child-like views of the world, the perspective of aliens and monsters or the compulsive habits of an eavesdropper shouting out loud. While drawing is at the centre of his practice, the artist also works across an extensive range of media including sculpture, large-scale installation, animation, painting, photography and music. Shrigley consistently seeks to widen his public by operating frequently outside the gallery sphere such as in prolific artist publications and collaborative music projects. His digital animations such as ‘Headless Drummer’ and ‘The Artist’ demonstrate what Shrigley calls ‘the economy of telling stories’, delivering a deftly crafted mix of dark and light through the simplest of forms. In his sculptural works that explore materials such as bronze and ceramic, the artist makes physical some of his more curious and eccentric propositions by transforming found objects or by playing with their scale. Taking Lewis Carroll's perspective of Wonderland, Shrigley enlarges objects and imbues them with curious proportions. Currently touring is ‘Lose Your Mind’ organized by the British Council. Venues include: Instituto Cultural Cabañas, Guadalajara, Mexico; MAC, Santiago, Chile; Storage by Hyundai Card, Seoul, Korea; Art Tower Mito, Japan. -

PRESS RELEASE – Rapid Response Fund First Acquisition Goma Final

PRESS RELEASE THE CONTEMPORARY ART SOCIETY’S RAPID RESPONSE FUND SUPPORTS MUSEUMS AND COMMUNITIES IN READING, LIVERPOOL AND GLASGOW AS DONATIONS PASS £200,000 • The CAS Rapid Response Fund, in partnership with Frieze London, is a new initiative supporting artists and museums during the Covid-19 pandemic. • Over £200,000 has already been raised, with a crowdfunding campaign raising the majority • As part of the crowdfunding campaign, limited-edition facemasks, designed by top artists – David Shrigley, Eddie Peake, Linder and Yinka Shonibare – are available for £35 each, or £120 for all four until 10 June 2020 • The CAS Rapid Response Fund will be used to purchase works by artists to add to collections of museums across the UK – ensuring financial support goes where it is needed most • Today, CAS announces the first recipients of the CAS Rapid Response Fund with more recipients to be announced each month [WEDNESDAY 3 June] Three works by Glasgow-born artist Rabiya Choudhry are among the first acquisitions through the Contemporary Art Society’s Rapid Response Fund following a crowdfunding campaign that has raised total donations to over £200,000. The works are being donated to GoMA, Glasgow and will form the centrepiece of their reopening exhibition Domestic Bliss, following the lifting of lockdown restrictions. The acquisition is one of three awards to be made by the fund, since its launch in May, alongside pieces by Eleanor Lakelin (Reading Museum) and Granby Workshop (The Victoria Gallery & Museum). A neon work, Dad (2018) puts her father’s name ‘Mazhar’ in lights, celebrating Glasgow’s Asian community and her father’s occupation as a shop owner, now classed as ‘essential workers’ during the Covid-19 crisis. -

Song List by Artist

song artist album label dj year-month-order sample of the whistled language silbo Nina 2006-04-10 rich man’s frug (video - movie clip) sweet charity Nayland 2008-03-07 dungeon ballet (video - movie clip) 5,000 fingers of dr. t Nayland 2008-03-08 plainfin midshipman the diversity of animal sounds Nina 2008-10-10 my bathroom the bathrooms are coming Nayland 2010-05-03 the billy bee song Nayland 2013-11-09 bootsie the elf bootsie the elf Nayland 2013-12-10 david bowie, brian eno and tony visconti record 'warszawa' Dan 2015-04-03 "22" with little red, tangle eye, & early in the mornin' hard hair prison songs vol 1: murderous home rounder alison 1998-04-14 phil's baby (found by jaime fillmore) the relay project (audio magazine) Nina 2006-01-02 [unknown title] [unknown artist] cambodian rocks (track 22) parallel world bryan 2000-10-01 hey jude (youtube video) [unknown] Nina 2008-03-09 carry on my wayward son (youtube video) [unknown] Nina 2008-03-10 Sri Vidya Shrine Prayer [unknown] [no album] Nina 2016-07-04 Sasalimpetan [unknown] Seleksi Tembang Cantik Tom B. 2018-11-08 i'm mandy, fly me 10cc changing faces, the best of 10cc and polydor godley & crème Dan 2003-01-04 animal speaks 15.60.76 jimmy bell's still in town Brian 2010-05-02 derelicts of dialect 3rd bass derelicts of dialect sony Brian 2001-08-09 naima (remix) 4hero Dan 2010-11-04 magical dream 808 state tim s. 2013-03-13 punchbag a band of bees sunshine hit me astralwerks derick 2004-01-10 We got it from Here...Thank You 4 We the People...