The Right of Newspapers to Defame ; C ::-*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Law School Record, Vol. 11, No. 1 (Winter 1963) Law School Record Editors

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound The nivU ersity of Chicago Law School Record Law School Publications Winter 1-1-1963 Law School Record, vol. 11, no. 1 (Winter 1963) Law School Record Editors Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolrecord Recommended Citation Law School Record Editors, "Law School Record, vol. 11, no. 1 (Winter 1963)" (1963). The University of Chicago Law School Record. Book 29. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolrecord/29 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in The University of Chicago Law School Record by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO 11 Volume WINTER 1963 Number 1 Seven New Appointments The Class of 1965 Four new members, including one from Ghana, have The class entering the School in October, besides being been to the of the Law School. appointed Faculty of excellent quality, shows great diversity of origins, both Three distinguished lawyers from abroad also have as to home states and undergraduate degrees. The 149 been members of the appointed visiting Law School students in the class come to the School from thirty-six faculty during 1963. states, plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico; they hold degrees from eighty-four different universities Continued on page 12 At the dinner for entering students, Visiting Committee and Alumni Board, left to right: Kenneth Montgomery, Charles R. Kaufman, Edmund Kitch, Class of 1964, Paul Kitch, JD'35, and Charles Boand, JD'33. -

Chancellor Kent: an American Genius

Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 38 Issue 1 Article 1 April 1961 Chancellor Kent: An American Genius Walter V. Schaefer Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Walter V. Schaefer, Chancellor Kent: An American Genius, 38 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 1 (1961). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol38/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. CHICAGO-KENT LAW REVIEW Copyright 1961, Chicago-Kent College of Law VOLUME 38 APRIL, 1961 NUMBER 1 CHANCELLOR KENT: AN AMERICAN GENIUS Walter V. Schaefer* T HIS IS THE FIRST OPPORTUNITY I have had, during this eventful day, to express my deep appreciation of the honor that you have done me.' I realize, of course, that there is a large element of symbolism in your selection of Dr. Kirkland and me to be the recipients of honorary degress, and that through him you are honoring the bar of our community, and through me the judges who man its courts. Nevertheless, both of us are proud and happy that your choice fell upon us. I am particularly proud to have been associated with Weymouth Kirkland on this occasion. His contributions to his profession are many. One of the most significant was the pioneer role that he played in the development of a new kind of court room advocacy. -

Censorship and Journalists' Privilege

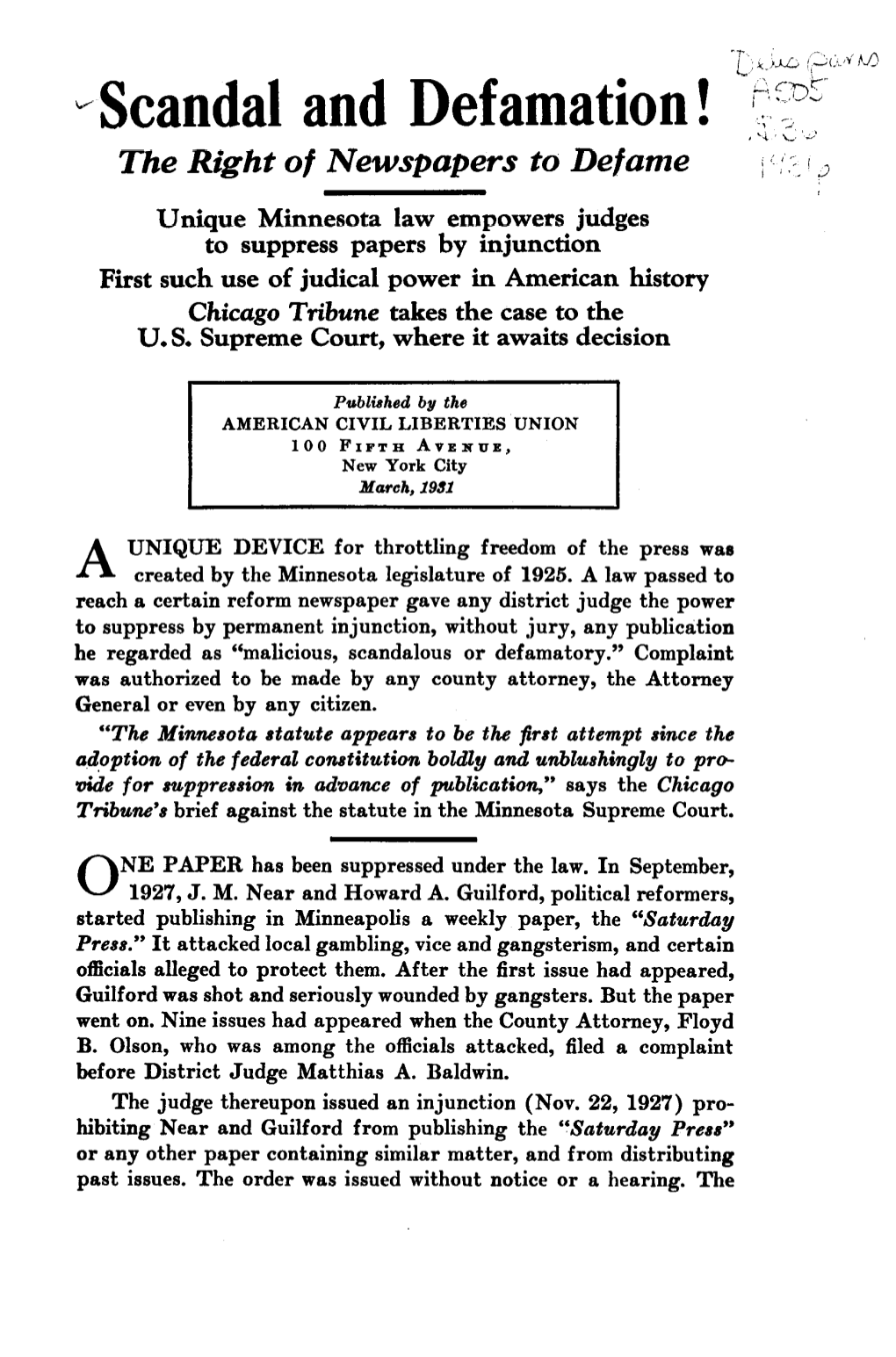

From the Archives An occasional series spotlighting captivating and relevant scholarship from back issues of Minnesota History. “Censorship and Journalists’ Privilege” was an edited version of a talk given by journalist Fred Friendly at the 1978 annual meeting and history conference of the Minnesota Historical Society. It was published in the Winter 1978 issue. meantime restrained, and they are hereby forbidden to Censorship and produce, edit, publish, circulate, have in their possession, Journalists’ Privilege sell or give away any publication known by any other name whatsoever containing malicious, scandalous, and The Case of Near versus Minnesota— defamatory matter of the kind alleged in plaintiff’s com- A Half Century Later plaint herein or otherwise.”4 His order was upheld five months later when Chief Justice Samuel B. Wilson declared for the majority of the Fred W. Friendly Minnesota Supreme Court: “In Minnesota no agency can hush the sincere and honest voice of the press; but our Although journalists tend to give all credit to the Constitution was never intended to protect malice, scan- Founding Fathers for freedom of the press, it was the dal, and defamation, when untrue or published without creative work of this century’s judiciary— Charles Evans justifiable ends.” By way of comparison Justice Wilson Hughes, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Louis D. Brandeis, noted that the constitutional guarantee of freedom of among others— that nationalized the First Amendment. assembly does not protect illegal assemblies, such as For it was only forty- eight years ago, in its [1931] decision riots, nor does it deny the state power to prevent them.5 in Near v. -

Law School Announcements 2017-2018 Law School Announcements Editors [email protected]

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound University of Chicago Law School Announcements Law School Publications Fall 2017 Law School Announcements 2017-2018 Law School Announcements Editors [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/ lawschoolannouncements Recommended Citation Editors, Law School Announcements, "Law School Announcements 2017-2018" (2017). University of Chicago Law School Announcements. 130. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolannouncements/130 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Law School Announcements by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago The Law School Announcements Fall 2017 Effective Date: September 1, 2017 This document is published on September 1 and its contents are not updated thereafter. For the most up-to-date information, visit www.law.uchicago.edu. 2 The Law School Contents OFFICERS AND FACULTY ........................................................................................................ 4 Officers of Administration and Instruction ................................................................ 4 Lecturers in Law ............................................................................................................ 8 Fellows ........................................................................................................................... -

Law School Record, Vol. 7, No. 1 (Fall 1957) Law School Record Editors

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound The nivU ersity of Chicago Law School Record Law School Publications Fall 9-1-1957 Law School Record, vol. 7, no. 1 (Fall 1957) Law School Record Editors Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolrecord Recommended Citation Law School Record Editors, "Law School Record, vol. 7, no. 1 (Fall 1957)" (1957). The University of Chicago Law School Record. Book 20. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolrecord/20 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in The University of Chicago Law School Record by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume 7 Number 1 ' ,';," . :},',�." .' :�i;.:· �,,�,,<.-,:-::,,�;;��(,>,.' :� ' . "., �:,�� ',' . "', .. l ! • , � -.I ,( ", • , 2 The Law School Record Vol. 7, No.1 Invocation Almighty God, creator and sustainer of all life, without whose bless ing and sufferance no human work can long prosper, we praise Thee for that which we have begun in this place and time. vVe thank Thee for the sense of justice which Thou hast implanted within mankind and for the readiness of men and communities to uphold and preserve a just order. We thank Thee for the dedication and vision of leaders in this com munity which have led to this new undertaking, for teachers and students committed to justice and human dignity, and for the noble heritage upon which this new venture is built. We pray, 0 God, for Thy guidance and direction in all our labors. -

![Near V. Minnesota [Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3431/near-v-minnesota-pdf-1743431.webp)

Near V. Minnesota [Pdf]

Near v. Minnesota 283 U.S. 697 Supreme Court of the United States June 1, 1931 5 NEAR v. MINNESOTA EX REL. OLSON, COUNTY ATTORNEY. No. 91. Argued January 30, 1931. Decided June 1, 1931. APPEAL FROM THE SUPREME COURT OF MINNESOTA. Mr. Weymouth Kirkland, with whom Messrs. Thomas E. Latimer, Howard Ellis, and Edward C. Caldwell were on the brief, for appellant. Messrs. James E. Markham, Assistant Attorney General of Minnesota, and Arthur L. Markve, Assistant County Attorney of Hennepin County, with whom Messrs. Henry N. Benson, Attorney General, John F. Bonner, 10 Assistant Attorney General, Ed. J. Goff, County Attorney, and William C. Larson, Assistant County Attorney, were on the brief, for appellee. MR. CHIEF JUSTICE HUGHES delivered the opinion of the Court. Chapter 285 of the Session Laws of Minnesota for the year 1925^ provides for the abatement, as a public nuisance, of a “malicious, scandalous and defamatory 15 newspaper, magazine or other periodical.” Section one of the Act is as follows: “Section 1. Any person who, as an individual, or as a member or employee of a firm, or association or organization, or as an officer, director, member or employee of a corporation, shall be engaged in the business of regularly or customarily producing, publishing or circulating, 20 having in possession, selling or giving away. (a) an obscene, lewd and lascivious newspaper, magazine, or other periodical, or (b) a malicious, scandalous and defamatory newspaper, magazine or other periodical, is guilty of a nuisance, and all persons guilty of such 25 nuisance may be enjoined, as hereinafter provided. -

School of Law Bulletin 1966-67.Pdf

INDIANA UNIVERSITY Bulletins for each of the following academic divisions of the University may be obtained from the Office of Records and Admissions, Bryan Hall, Indiana University, Bloom ington, Indiana 47405. COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES DIVISION OF OPTOMETRY DIVISION OF SOCIAL SERVICE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS SCHOOL OF DENTISTRY SCHOOL OF EDUCATION* DIVISION OF LIBRARY SCIENCE GRADUATE SCHOOL SCHOOL OF HEALTH, PHYSICAL EDUCATION, AND RECREATION NORMAL COLLEGE OF THE AMERICAN GYMNASTIC UNION SCHOOL OF LAW SCHOOL OF MEDICINE DIVISION OF ALLIED HEALTH SCIENCES SCHOOL OF MUSIC SCHOOL OF NURSING DIVISION OF UNIVERSITY EXTENSION SUMMER SESSIONS * A separate Bulletin is issued for the Graduate Division of the School of Education. BULLETIN OF THE SCHOOL OFLAW IN DIANA llll UNIVERSITY • 010 ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICERS Of the University ELVIS J. STAHR, B.C.L., LL.D., President of the University HERMAN B WELLS, A.M., LL.D., Chancellor of the University; President of the Indiana University Foundation SAMUEL E. BRADEN, Ph.D., Vice-President, and Dean for Undergraduate Development J A. FRANKLIN, B.S., Vice-President, and Treasurer RAYL. HEFFNER, JR., Ph.D., Vice-President, and Dean of the Faculties LYNNE L. MERRITT, JR., Ph.D., Vice-President for Research, and Dean of Advanced Studies CHARLES E. HARRELL, LL.B., Registrar, and Director of the Office of Records and Admissions Of the School of Law LEON H. WALLACE, JD., Dean BENJAMIN F. SMALL, JD., Associate Dean; Dean of the Indianapolis Division INDIANA UNIVERSITY BULLETIN (OFFICIAL SERIES) Second-class postage paid at Bloomington, Indiana. Published thirty times a year (five times each in November, January; four times in December; twice each in Octobi:r, March, April, May, June, July, September; monthly in February, August) by Indiana University frorn the Univer sity Office, Bloomington, Indiana. -

Law School Record, Vol. 9, No. 2 (Summer 1960) Law School Record Editors

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound The nivU ersity of Chicago Law School Record Law School Publications Summer 6-1-1960 Law School Record, vol. 9, no. 2 (Summer 1960) Law School Record Editors Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolrecord Recommended Citation Law School Record Editors, "Law School Record, vol. 9, no. 2 (Summer 1960)" (1960). The University of Chicago Law School Record. Book 27. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolrecord/27 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in The University of Chicago Law School Record by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 The Law School Record Vol. 9, No.2 The honorary degree of Doctor of Laws is conferred by Chan Court of Illinois. Justice Schaefer was escorted by Professor cellor Kimpton upon: upper left, the Honorable Earl Warren, Karl N. Llewellyn; lower left, the Honorable Charles E. Clark, Chief Justice of the United States. The Chief Justice was Chief Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sec escorted by Roscoe T. Steffen, John P. Wilson Professor of Law; ond Circuit. Judge Clark was escorted by Professor Bernard D. upper right, the Honorable Roger J. Traynor, Justice of the Meltzer; lower right, the Honorable Dag Hammarskjold, Secre Supreme Court of California. Justice Traynor was escorted by tary General of the United Nations. Dr. Hammarskjold was Professor Brainerd Currie; center left, the Honorable Herbert F. -

The Weymouth Kirkland Courtroom, in the New University of Chicago Law School Building

24 The Law School Record Vol. 7, No.1 A Distinguished Lawyer For some time, the Law School has sponsored a series of lectures on distinguished lawyers. The most recent talk in that series was delivered in November by Mr. John P. Wilson, of Wilson and McIlvaine, who spoke on the career of his father. Mr. Wilson's paper will be found elsewhere in this issue of the Record. Prior to his lecture, the Law Faculty was host to Mr. Wilson, his partners and their wives, and to third year law students, at a Quadrangle Club dinner. At the dinner honoring Mr. Weymouth Kirkland on his 80th birthday, announcement is made of the establishment of the Weymouth Kirkland. Courtroom in the new Law Building. Mr. Kirkland and Dean Levi am shown with a portrait of Mr. Kirkland, painted by Mrs. Howard Ellis, which now hangs in the Law Library. The Jf7f:Ymouth Kirkland Courtroom The eightieth birthday of Mr. Weymouth Kirkland proved to be a day of great importance to the Law School, as well as to Mr. Kirkland himself. Announce ment was made, as part of the birthday celebration, that colleagues and other friends of Mr. Kirkland had established, in his honor, the Weymouth Kirkland Courtroom, in the new University of Chicago Law School Building. The members uf [ohs» P. Wilson's finn and their wives were Mr. senior of Kirkland, Kirkland, partner Fleming, guests of the School at dinner, together with members of the Green, Martin and Ellis, has long been an eminent Law School's current senior class. -

Law School Announcements 1960-1961 Law School Announcements Editors [email protected]

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound University of Chicago Law School Announcements Law School Publications 8-31-1960 Law School Announcements 1960-1961 Law School Announcements Editors [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/ lawschoolannouncements Recommended Citation Editors, Law School Announcements, "Law School Announcements 1960-1961" (1960). University of Chicago Law School Announcements. Book 84. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolannouncements/84 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Law School Announcements by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOUNDED BY JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER Announcements The Law School FOR SESSIONS OF 1960 • 1961 TABLE OF CONTENTS OFFICERS OF ADMINISTRATION. OFFICERS OF INSTRUCTION • I. LocATION, HISTORY, AND ORGANIZATION 3 II. GENERAL STATEMENT 4 III. ADMISSION OF STUDENTS • • • • • • • • • • 4 Admission of Students to the Undergraduate (J.D.) Program . 4 Admission of Students to the Graduate (LL.M.) (J.S.D.) Program 5 Admission of Students to the Certificate Program. 5 Admission of Students to the Graduate Comparative Law and Foreign Law Programs . 5 IV. REQUIREMENTS FOR DEGREES 5 The Undergraduate Program 5 The Graduate Program 6 The Certificate Program . 6 The Graduate Comparative Law Program 6 The Foreign Law Program 7 V. EXAMINATIONS, GRADING, AND RULES 7 VI. COURSES OF INSTRUCTION • 8 First-Year Courses. 8 Second- and Third-Year Courses . 8 Seminars. 11 Courses for the Summer Session, 1960 13 Courses for the Summer Session, 1961 13 VII. -

Robert R. Mccormick and Near V. Minnesota

Federal Communications Law Journal Volume 60 Issue 2 Article 3 3-2008 The Colonel's Finest Campaign: Robert R. McCormick and Near v. Minnesota Eric B. Easton University of Baltimore School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/fclj Part of the Communications Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, Fourth Amendment Commons, Legislation Commons, and the Litigation Commons Recommended Citation Easton, Eric B. (2008) "The Colonel's Finest Campaign: Robert R. McCormick and Near v. Minnesota," Federal Communications Law Journal: Vol. 60 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/fclj/vol60/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Federal Communications Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Colonel's Finest Campaign: Robert R. McCormick and Near v. Minnesota Eric B. Easton* I. NEAR V. MINNESOTA: BACKGROUND ...................................... 185 II. INCORPORATION: THE NECESSARY PRECONDITION .............. 188 III. COL. MCCORMICK TAKES CHARGE OF NEAR ........................ 196 IV. BEFORE THE SUPREME COURT ............................................... 216 V . THE D ECISION ........................................................................ 221 VI. THE AFTERM ATH .................................................................... 226 "The mere statement of the case makes my blood boil." So wrote Weymouth Kirkland to his most illustrious client, Col. Robert R. McCormick of The Chicago Tribune ("Tribune") on Sept. 14, 1928.' The prominent Chicago attorney was writing about a case then styled State ex rel. Olson v. Gui/ford,2 but which would make history as Near v. -

CENTS ORTS—FOREIQH NT M MORE Oeeaai Trawej."*" Xlxltik J S^P the WORLD's GREATEST NEWSPAPER - •

3BER 15, 19^ CENTS ORTS—FOREIQH NT M MORE Oeeaai Trawej."*" XLXLtiK J s^P THE WORLD'S GREATEST NEWSPAPER - • . VOLUME LXXX.—NO. 42. [COPYRIGHT: 1821: ^T fnited BT THE CHICAGO TBIBUNB.l OCTOBER 16, 1921. H^RADI^ totes A * SEVEN CENTS 8 i TEN CENTS ELSEWHERE. Lines TORI^TO EUROPB md_J. Hoboktn) «xrtSJ rM-CHER3- i: ••"S*» Hew. !—?»••. WASHINGTON TH-BOULOCNE—LONDOlt -i u in r •<>«•—ComforteMe. I STATE: On. to— NaT. —» fc, „ OLD AND TtoUNG X STATE: Na«r. «- jg^ * JUDGE UPHOLDS OF IRELAND SEEK HOW TO INSPIRE RESPECT FOR THE LAW IR EM EN-DANZIG FOUR CONVICTIONS WOULD DO IT. POLICE BATTLE WHAT CALL FfiR •tATOIEA: Oct. SS—Dae., AMERICAN HAVEN 2 MILLION MEN >-•«. i*-»••. at- TRIBUNE PLEA [Copyright: 1921: By The Chicago Tribune.! BIGGEST RAIL D STATES LINES, Troubles Are Many SAFEBLOWERS; TO DESERT JILL Broadway, N. Y. IcCORMACK COMPANY t*C ' Before They Sail. STRIKE MEANS STEAMSHIP COMPANY Wc The following article is one oi a AMERICAN LINES. INC. FOR FREE PRESS Strike order issued by five brother series by Miss Genevieve Forbes, a KILL 2, JAIL 1 HH</ Off rotors for the hood chiefs, cajlinp oat 500,000 men ROADS BY NOV. 2 member of The Tribune staff, who States Shipping Board Oct. 30. Complete tieup of the coun *t*s just returned to America, pass- try's 200,000 miles of trackage expected IJAT through Ellis island as an I risk by Nov. 2, lesving 2,000,000 workers Rules Against City immigrant girl. Miss Forbes had Yeggs Shoot It Out jobless. some remarkable experiences in Ire Trains Will Move, Is in Libel Suit.