IJEL-“The Mountains of the Moon” Thomas Vaughan, Poe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Kabbalah, Symbolism and Metaphysicsin Russian Freemasonry of the XVIII Th–XIX Th Centuries

REHMLAC. Revista de Estudios Históricos de la Masonería Latinoamericana y Caribeña E-ISSN: 1659-4223 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica Khalturin, Yuriy Kabbalah, Symbolism and Metaphysicsin Russian Freemasonry of the XVIII th–XIX th centuries REHMLAC. Revista de Estudios Históricos de la Masonería Latinoamericana y Caribeña, vol. 7, núm. 1, mayo-noviembre, 2015, pp. 128-140 Universidad de Costa Rica San José, Costa Rica Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=369539930009 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative REHMLAC+, ISSN 1659-4223, Vol. 7, no. 2, Mayo - Noviembre 2015/ 128-140 128 Kabbalah, Symbolism and Metaphysics in Russian Freemasonry of the XVIIIth – XIXth centuries Yuriy Khalturin PhD in Philosophy (Russian Academy of Science), independent scholar, member of ESSWE. E-mail: [email protected] Fecha de recibido: 20 de noviembre de 2014 - Fecha de aceptación: 8 de enero de 2015 Palabras clave Cábala, masonería, rosacrucismo, teosofía, sofilogía, Sephiroth, Ein-Soph, Adam Kadmon, emanación, alquimia, la estrella llameante, columnas Jaquín y Boaz Keywords Kabbalah, Freemasonry, Rosicrucianism, Theosophy, Sophiology, Sephiroth, Ein-Soph, Adam Kadmon, emanation, alchemy, Flaming Star, Columns Jahin and Boaz Resumen Este trabajo considera algunas conexiones entre la Cábala y la masonería en Rusia como se refleja en los archivos del Departamento de Manuscritos de la Biblioteca Estatal Rusa (DMS RSL). El vínculo entre ellos se basa en la comprensión tanto de la Cabala y la masonería como la filosofía simbólica y “verdaderamente metafísica”. -

Rosicrucianism from Its Origins to the Early 18Th Century

CHAPTER TWO ROSICRUCIANISM FROM ITS ORIGINS TO THE EARLY 18TH CENTURY In order to understand the 18th-century Rosicrucian revival it is necessary to know something of the origins and early history of Rosicrucianism. This ground has already been covered many times,1 but it is worth covering it again here in broad outline as a prelude to my main investigation. The Rosicrucian legend was born in the early 17th century in the uneasy period before religious tensions in Central Europe erupted into the Thirty Years' War. The Lutheran Reformation of a century earlier had finally shat tered the religious unity of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. On the other hand, as the historian Geoffrey Parker has observed, the Reformation had not produced the spiritual renewal that its advocates had hoped for.2 In the prevailing atmosphere of political and religious tension and spiritual malaise, many people turned, in their dismay, to the old millenarian dream of a new age. This way of thinking, dating back to the writings of the 12th-cen tury Calabrian abbot Joachim of Fiore, had surfaced at various times in the intervening centuries, giving rise to movements of the kind described by Nor man Cohn in his Pursuit of the Millennium3 and by Marjorie Reeves in her Joachim ofFiore and the Prophetic Future.4 Joachim and his followers saw history as unfolding in a series of three ages, corresponding to the three per sons of the Trinity: Father, Son and Holy Spirit, in that order. They believed that hitherto they had been living in the Age of the Son, but that the Age of the Spirit was at hand. -

Rosicrucianism in the Contemporary Period in Denmark

Contemporary Rosicrucianism in Denmark 445 Chapter 55 Contemporary Rosicrucianism in Denmark Rosicrucianism in the Contemporary Period in Denmark Jacob Christiansen Senholt Rosicrucian ideas were present in Denmark already during the seventeenth century, fuelled by the publication of the tracts Fama fraternitatis rosae crucis and Confessio fraternitatis in Germany in 1614 and 1615 respectively. After a gap in the history of Rosicrucian presence in Denmark of almost 300 years, modern Rosicrucian societies spread across the world, and following this wave of Rosi cru cian fraternities, Danish offshoots of these fraternities also emerged. The modernday Rosicrucians and their presence in Denmark stem from two differ ent historical roots. The first is an influence from Germany via the Rosicrucian Society in Germany (RosenkreuzerGesellschaft in Deutschland), and the other comes from the United States, with the formation of Antiquus Mys ti cus que Ordo Rosæ Crucis (AMORC) by Harvey Spencer Lewis (1883–1939) in 1915. The Rosicrucian Fellowship The history of modern Rosicrucianism in Denmark starts in 1865 when Carl Louis von Grasshoff (1865–1919), later known under the pseudonym Max Heindel, was born. Although born in Denmark, Heindel was of German ances try, and spent most of his life travelling in both the United States and Germany. He was a member of the Theosophical Society and met with the later founder of Anthroposophy, Rudolf Steiner, in 1907. In 1909 he published his major work, The Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception, which dealt with Christian mysticism and esotericism, and later that year Heindel founded The Rosicrucian Fellowship. It was a German spinoff of this group lead by occultist and theosophist Franz Hartmann (1838–1912) and later Hugo Vollrath, that later became influential in Denmark. -

Interactive Timeline

http://knowingpoe.thinkport.org/ Interactive Timeline Content Overview This timeline includes six strands: Poe’s Life, Poe’s Literature, World Literature, Maryland History, Baltimore History and American History. Students can choose to look at any or all of these strands as they explore the timeline. You might consider asking students to seek certain items in order to give students a picture of Poe as a writer and the life and times in which he worked. This is not an exhaustive timeline. It simply highlights the major events that happened during Poe’s lifetime. Poe’s Life Edgar Poe is born in Boston on January 19. 1809 Elizabeth Arnold Poe, Poe’s mother, dies on December 8 in Richmond, Virginia. 1811 David Poe, Poe’s mother, apparently dies within a few days. John and Frances Allen adopt the young boy. The Allans baptize Edgar as Edgar Allan Poe on January 7. 1812 Poe begins his schooling 1814 The Allans leave Richmond, bound for England. 1815 Poe goes to boarding school. His teachers refer to him as “Master Allan.” 1816 Poe moves to another English school. 1818 The Allans arrive back in America, stopping for a few days in New York City 1820 before returning to Richmond. Poe continues his schooling. 1821 Poe swims against a heavy tide six or seven miles up the James River. 1824 In November, he also writes a two-line poem. The poem was never published. John Allan inherits a great deal of money and buys a huge mansion in Richmond 1825 for his family to live in. -

Theosophical Siftings Christian Rosenkreuz and the Rosicrucians Vol 6, No 15 Christian Rosenkreuz and the Rosicrucians

Theosophical Siftings Christian Rosenkreuz and the Rosicrucians Vol 6, No 15 Christian Rosenkreuz and the Rosicrucians by William Wynn Westcott Reprinted from "Theosophical Siftings" Volume 6 The Theosophical Publishing Society, England [Page 3] THE Rosicrucians of mediaeval Germany formed a group of mystic philosophers, assembling, studying and teaching in private the esoteric doctrines of religion, philosophy and occult science, which their founder, Christian Rosenkreuz, had learned from the Arabian sages, who were in their turn the inheritors of the culture of Alexandria. This great city of Egypt, a chief emporium of commerce and a centre of intellectual learning, flourished before the rise of the Imperial power of Rome, falling at length before the martial prowess of the Romans, who, having conquered, took great pains to destroy the arts and sciences of the Egypt they had overrun and subdued ; for they seem to have had a wholesome fear of those magical arts, which, as tradition had informed them, flourished in the Nile Valley; which same tradition is also familiar to English people through our acquaintance with the book of Genesis, whose reputed author was taught in Egypt all the science and arts he possessed, even as the Bible itself tells us, although the orthodox are apt to slur over this assertion of the Old Testament narrative. Our present world has taken almost no notice of the Rosicrucian philosophy, nor until the last twenty years of any mysticism, and when it does condescend to stoop from its utilitarian and money-making occupations, it is only to condemn all such studies, root and branch, as waste of time and loss of energy. -

Track Title 1 Tamerlane 2 Song 3 Dreams 4 Spirits Of

Track Title 1 Tamerlane 2 Song 3 Dreams 4 Spirits of the Dead 5 Evening Star 6 A Dream 7 The Lake To 8 Alone 9 Sonnet - To Science 10 Al Aaraaf 11 To - "The bowers whereat..." 12 To the River … 13 To - "I heed not that my..." 14 Fairyland 15 To Helen 16 Israfel 17 The Sleeper 18 The Valley of Unrest 19 The City and the Sea 20 A Paean 21 Romance 22 Loss of Breath 23 Bon-Bon 24 The Duc De L'Omelette 25 Metzengerstein 26 A Tale of Jerusalem 27 To One in Paradise 28 The Assignation 29 Silence - A Fable 30 MS. Found in a Bottle 31 Four Beasts in One 32 Bérénice 33 King Pest 34 The Coliseum 35 To F--s. S. O--d 36 Hymn 37 Morella 38 Unparallelled Adventure of One Hans Pfall 39 Unparallelled Adventure of One Hans Pfall (continued) 40 Lionizing 41 Shadow - A Parable 42 Bridal Ballad 43 To Zante 44 Maelzel's Chess Player 45 Magazine Writing - Peter Snook 46 Narritive of A. Gordon Pym 47 Narritive of A. Gordon Pym (continued) 48 Narritive of A. Gordon Pym (continued) 49 Narritive of A. Gordon Pym (continued) 50 Narritive of A. Gordon Pym (continued) 51 Mystification 52 Ligeia 53 How to Write a Blackwood Article 54 A Predicament 55 Why the Little Frechman Wears His Hand in a Sling 56 The Haunted Palace 57 Silence 58 The Devil in the Belfry 59 William Wilson 60 The Man that was Used Up 61 The Fall of the House of Usher 62 The Business Man 63 The Man of the Crowd 64 The Murders of the Rue Morgue 65 The Murders of the Rue Morgue (continued) 66 Eleonora 67 A Descent into the Maelstrom 68 The Island of the Fay 69 Never Bet the Devil Your Head 70 Three Sundays in a Week 71 The Conqueror Worm 72 Lenore 73 The Oval Portrait 74 The Masque of the Red Death 75 The Pit and the Pendulum 76 The Mystery of Marie Roget 77 The Mystery of Marie Roget (continued) 78 The Domain of Arnheim 79 The Gold-Bug 80 The Gold-Bug (continued) 81 The Tell-Tale Heart 82 The Black Cat 83 Raising the Wind (a.k.a. -

INTRODUCTION Rosicrucianism Is a Theosophy Advanced by an Invisible

INTRODUCTION Rosicrucianism is a theosophy advanced by an invisible order of spir itual knights who in spreading Christian Hermeticism, Kabbalah, and Gnosis seek to enliven and to preserve the memory of Divine Wisdom, understood as a feminine flame of love called Sofia or Shekhinah, exoterically given as a fresh unfolded rose, yet, more akin to the blue fire of alchemy, the blue virgin. Rosicrucians have no organisation and there are no recognizable Rosicrucian individuals, but the order makes its presence known by leaving behind engram- matic writings in the genre of Hermetic-Platonic Christianity.1 The historical roots of Hermeticism is to be located in Ancient Egypt. Long before the rise of Christianity, Hermetic texts were struc tured around the belief that organisms contain sparks of a Divine mind unto which they each strive to attend. Things easily transform into others, thereby generating certain cyclical patterns, cycles that peri odically renew themselves on a cosmic scale. These transformations of life and death were enacted in the Hermetic Mysteries in Ancient Egypt through the gods Isis, Horus, and Osiris. In the Alexandrian period these myths were reshaped into Hermetic discourses on the transformations of the self with Thot, the scribal god. These dis courses were introduced in the west in 1474 when Marsilio Ficino translated the Hermetic Pimander from the Greek. The story of Chris tian Rosencreutz can be seen as a new version of these mysteries, specifically tempered by German Paracelsian philosophy on the lion of the darkest night, a biblical icon for how the higher self lies slum bering in consciousness.2 In this book, I develop the Rosicrucian theme from a Scandinavian perspective by linking selected historical events to scenarios of the emergence of European Rosicrucianism that have been advanced from other geographic angles. -

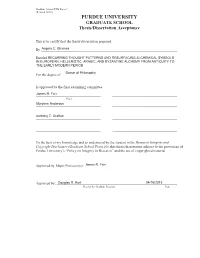

PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance

Graduate School ETD Form 9 (Revised 12/07) PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By Angela C. Ghionea Entitled RECURRING THOUGHT PATTERNS AND RESURFACING ALCHEMICAL SYMBOLS IN EUROPEAN, HELLENISTIC, ARABIC, AND BYZANTINE ALCHEMY FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD Doctor of Philosophy For the degree of Is approved by the final examining committee: James R. Farr Chair Myrdene Anderson Anthony T. Grafton To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Research Integrity and Copyright Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 20), this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy on Integrity in Research” and the use of copyrighted material. Approved by Major Professor(s): ____________________________________James R. Farr ____________________________________ Approved by: Douglas R. Hurt 04/16/2013 Head of the Graduate Program Date RECURRING THOUGHT PATTERNS AND RESURFACING ALCHEMICAL SYMBOLS IN EUROPEAN, HELLENISTIC, ARABIC, AND BYZANTINE ALCHEMY FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Angela Catalina Ghionea In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana UMI Number: 3591220 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3591220 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

Historical Influence of the Rosicrucian Fraternity on Freemasonry

Historical Influence of the Rosicrucian Fraternity on Freemasonry Introduction Freemasonry has a public image that sometimes includes notions that we practice some sort of occultism, alchemy, magic rituals, that sort of thing. As Masons we know that we do no such thing. Since 1717 we have been a modern, rational, scientifically minded craft, practicing moral and theological virtues. But there is a background of occult science in Freemasonry, and it is related to the secret fraternity of the Rosicrucians. The Renaissance Heritage1 During the Italian renaissance of the 15th century, scholars rediscovered and translated classical texts of Plato, Pythagoras, and the Hermetic writings attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, thought to be from ancient Egypt. Over the next two centuries there was a widespread growth in Europe of various magical and spiritual practices – magic, alchemy, astrology -- based on those texts. The mysticism and magic of Jewish Cabbala was also studied from texts brought from Spain and the Muslim world. All of these magical practices had a religious aspect, in the quest for knowledge of the divine order of the universe, and Man’s place in it. The Hermetic vision of Man was of a divine soul, akin to the angels, within a material, animal body. By the 16th century every royal court in Europe had its own astrologer and some patronized alchemical studies. In England, Queen Elizabeth had Dr. John Dee (1527- 1608) as one of her advisors and her court astrologer. Dee was also an alchemist, a student of the Hermetic writings, and a skilled mathematician. He was the most prominent practitioner of Cabbala and alchemy in 16th century England. -

View Fast Facts

FAST FACTS Author's Works and Themes: Edgar Allan Poe “Author's Works and Themes: Edgar Allan Poe.” Gale, 2019, www.gale.com. Writings by Edgar Allan Poe • Tamerlane and Other Poems (poetry) 1827 • Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane, and Minor Poems (poetry) 1829 • Poems (poetry) 1831 • The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, North America: Comprising the Details of a Mutiny, Famine, and Shipwreck, During a Voyage to the South Seas; Resulting in Various Extraordinary Adventures and Discoveries in the Eighty-fourth Parallel of Southern Latitude (novel) 1838 • Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque (short stories) 1840 • The Raven, and Other Poems (poetry) 1845 • Tales by Edgar A. Poe (short stories) 1845 • Eureka: A Prose Poem (poetry) 1848 • The Literati: Some Honest Opinions about Authorial Merits and Demerits, with Occasional Words of Personality (criticism) 1850 Major Themes The most prominent features of Edgar Allan Poe's poetry are a pervasive tone of melancholy, a longing for lost love and beauty, and a preoccupation with death, particularly the deaths of beautiful women. Most of Poe's works, both poetry and prose, feature a first-person narrator, often ascribed by critics as Poe himself. Numerous scholars, both contemporary and modern, have suggested that the experiences of Poe's life provide the basis for much of his poetry, particularly the early death of his mother, a trauma that was repeated in the later deaths of two mother- surrogates to whom the poet was devoted. Poe's status as an outsider and an outcast--he was orphaned at an early age; taken in but never adopted by the Allans; raised as a gentleman but penniless after his estrangement from his foster father; removed from the university and expelled from West Point--is believed to account for the extreme loneliness, even despair, that runs through most of his poetry. -

Overthrowing Optimistic Emerson: Edgar Allan Poe’S Aim to Horrify Nicole Vesa the Laurentian University at Georgian College

Comparative Humanities Review Volume 1 Article 8 Issue 1 Conversation/Conversion 1.1 2007 Overthrowing Optimistic Emerson: Edgar Allan Poe’s Aim to Horrify Nicole Vesa The Laurentian University at Georgian College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/chr Recommended Citation Vesa, Nicole (2007) "Overthrowing Optimistic Emerson: Edgar Allan Poe’s Aim to Horrify ," Comparative Humanities Review: Vol. 1: Iss. 1, Article 8. Available at: http://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/chr/vol1/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Humanities Review by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Overthrowing Optimistic Emerson: Edgar Allan Poe’s Aim to Horrify Nicole Vesa The Laurentian University at Georgian College The 19th century writer, Edgar Allan Poe, creates a dark view of the human mind in his poetry, which serves to challenge Ralph Waldo Emerson’s popular belief in optimism. The idea of beauty is important in both Poe’s and Emerson’s thinking, yet Poe’s view of atmospheric beauty confronts Emerson’s view of truth and intelligence as beauty. The compo- sition of poetry, in Poe’s opinion, is a mechanical, rough, and timely process. Poe argues against Emerson’s belief that the poet is inspired by an idea, and then effortlessly creates the poem, with the form coming into place naturally. Emerson believes that mankind is in charge of its own destiny, and seeks for higher reasoning. Poe challenges this idea, and argues that the human psyche is instinctual, and therefore humans can not control their desire for the perverse. -

Nevermore: the Final Nightmares of Edgar Allan Poe

Nevermore: The Final Nightmares of Edgar Allan Poe a study guide compiled and arranged by the Education Department of The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey’s Shakespeare LIVe! 2008 educational touring production The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey Nevermore study guide — 2 Nevermore: The Final Nightmares of Edgar Allan Poe a study guide a support packet for studying the play and attending The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey’s Shakespeare LIVE! touring production General Information p3- Using this Study Guide p13- Sources for this Study Guide Edgar Allan Poe and his Times p4- A Brief Biography of Edgar Allan Poe p5- The Mysterious Death of E.A. Poe p6- Mental Illness and Treatment in the 1800s p10- Poe’s Times: Chronology Nevermore and Poe’s Writings p7- Nevermore: A Brief Synopsis p8- Commentary and Criticism p9- Nevermore: Food For Thought Classroom Applications p10- Terms and Phrases found in Nevermore p11- Additional Topics for Discussion p11- Follow-Up Activities p12- “Test Your Understanding” Quiz p13- Meeting The Core Curriculum Standards p13- “Test Your Understanding” Answer Key About The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey p14- About The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey p14- Other Opportunities for Students... and Teachers Lead support for Shakespeare LIVE! is provided by a generous grant from Kraft Foods. Additional funding for Shakespeare LIVE! is provided by Verizon, The Turrell Fund, The Horizon Foundation for New Jersey, JPMorgan Chase Foundation, Pfizer, PSE&G, The Altschul Foundation, Van Pelt Foundation, PricewaterhouseCoopers, The Ambrose and Ida Frederick- son Foundation, and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp. The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey’s programs are made possible in part by funding from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts/ Department of State, a Partner Agency of the National Endowment for the Arts, and by funds from the National Endowment for the Arts.