Economic Impacts of the Wisconsin State Park System: Connections to Gateway Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lexicon of Pleistocene Stratigraphic Units of Wisconsin

Lexicon of Pleistocene Stratigraphic Units of Wisconsin ON ATI RM FO K CREE MILLER 0 20 40 mi Douglas Member 0 50 km Lake ? Crab Member EDITORS C O Kent M. Syverson P P Florence Member E R Lee Clayton F Wildcat A Lake ? L L Member Nashville Member John W. Attig M S r ik be a F m n O r e R e TRADE RIVER M a M A T b David M. Mickelson e I O N FM k Pokegama m a e L r Creek Mbr M n e M b f a e f lv m m i Sy e l M Prairie b C e in Farm r r sk er e o emb lv P Member M i S ill S L rr L e A M Middle F Edgar ER M Inlet HOLY HILL V F Mbr RI Member FM Bakerville MARATHON Liberty Grove M Member FM F r Member e E b m E e PIERCE N M Two Rivers Member FM Keene U re PIERCE A o nm Hersey Member W le FM G Member E Branch River Member Kinnickinnic K H HOLY HILL Member r B Chilton e FM O Kirby Lake b IG Mbr Boundaries Member m L F e L M A Y Formation T s S F r M e H d l Member H a I o V r L i c Explanation o L n M Area of sediment deposited F e m during last part of Wisconsin O b er Glaciation, between about R 35,000 and 11,000 years M A Ozaukee before present. -

Superior Coastal Plain Regional Master Plan

Superior Coastal Plain Regional Master Plan February 2019 PUB-LF-112 (2018) Superior Coastal Plain Regional Master Plan Approved by the Natural Resources Board February 27, 2019 Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Preston D. Cole – Secretary Natural Resources Board Dr. Frederick Prehn, Chair Greg Kazmierski, Vice Chair Julie Anderson, Secretary William Bruins Terry N. Hilgenberg Gary Zimmer Fred Clark 101 S. Webster St, P.O. Box 7921 Madison, WI 53707-7921 DNR PUB–LF–112 i The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources provides equal opportunity in its employment, programs and services and functions under an Affirmative Action Plan. If you have any questions, please write to the Equal Opportunity Office, Department of the Interior, Washington D.C. 20240. This publication is available in alternative formats (large print, Braille, audio tape, etc.) upon request. Please contact the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Bureau of Facilities and Lands at 608-266-2135 for more information. This publication is available online at http://dnr.wi.gov, keyword search “Property Planning.” Click on the Superior Coastal Plain region to download this document in PDF form. Cover Photo by Kevin Feind, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources ii REGIONAL MASTER PLAN TEAM MEMBERS CORE TEAM Pat Beringer Wildlife Management Supervisor Cameron Bump Northwest Recreation Liaison Nancy Christel Wildlife Biologist Robert Hanson Wildlife Biologist Steve Hoffman Wildlife Management Supervisor Dave Kafura Forest Hydrologist Nolan Kriegel Forester Ryan Magana -

48 Hours in La Crosse This Mississippi River City Is a Must-Stop 100 Years of Gridiron Glory the PACK CELEBRATES THEIR CENTENNIAL

experience WISCONSIN Fall/Winter 2018-19 48 Hours in La Crosse This Mississippi River City is a Must-Stop 100 Years of Gridiron Glory THE PACK CELEBRATES THEIR CENTENNIAL Whitewater’s Farm Boy to Rising-Star Chef COME GET YOUR WE’RE YOUR FOR THAT PERFECT Bet DAY TRIP OVERB 1,200est SLOT MACHINES | 100% SMOKE-FREE | DINING | BAR BEEN WANTING TO TAKE A DAY TRIP? 51 39 Visit Madison’s Casino and have a little fun! We have the most 90 generous slot machines in the region with an average payout of 95%. Play any of our 1,200 themed slot machines while enjoying 12 your favorite adult beverage on our Smoke-Free gaming floor. 4002 EVAN ACRES RD., MADISON, WI 53718 | 608.223.9576 MADISON ho-chunkgaming.com/madison HCGM-FG.indd 1 8/7/18 4:16 PM US This Fall JOIN eat Events! for Gr ONEIDA BIG APPLE FEST September 22 Oneida Apple Orchard & Cultural Heritage Center GREAT NORTHEAST SCENERY WISCONSIN CRAFT BEER FESTIVAL October 6 GREAT Shopko Hall FOOD CIRQUE DU SOLEIL CRYSTAL October 11-14 Resch Center ZOO BOO October 12-13, 19-20, 26-27 NEW Zoo & Adventure Park GREAT PUMPKIN TRAIN GREAT October 13 & 20 National Railroad Museum TEAM For a complete listing of Green Bay events, visit GreenBay.com. Call for Your FREE Guide to Green Bay 888-867-3342 GREAT FUN fall/winter 2018-19 | experiencewisconsinmag.com | 3 Wisconsin’s Best Shopping SHOP • DINE • EXPLORE • EXPERIENCE Start planning your getaway today at FoxCities.org YOU ARE HERE BRINGING Lake Superior YOU HOME for over 70 years LUXURY PORTFOLIO LUXURY PORTFOLIO JEWEL OF KENOSHA COUNTY EXQUISITE ON 11+ ACRES Bayfield Apostle Superior Islands BRULE Washburn RIVER STATE Ashland Lake Brule Nebagamon FOREST 2 13 Montreal Hurley Solon Springs CHEQUAMEGON Gile Flowage St. -

Wisconsin Great River Road, Thank You for Choosing to Visit Us and Please Return Again and Again

Great River Road Wisc nsin Travel & Visitors Guide Spectacular State Bring the Sights Parks Bike! 7 22 45 Wisconsin’s National Scenic Byway on the Mississippi River Learn more at wigrr.com THE FRESHEST. THE SQUEAKIEST. SQUEAk SQUEAk SQUEAk Come visit the Cheese Curd Capital and home to Ellsworth Premium Cheeses and the Antonella Collection. Shop over 200 kinds of Wisconsin Cheese, enjoy our premium real dairy ice cream, and our deep-fried cheese curd food trailers open Thursdays-Sundays all summer long. WOR TWO RETAIL LOCATIONS! MENOMONIE LOCATION LS TH L OPEN 7 DAYS A WEEK - 8AM - 6PM OPENING FALL 2021! E TM EST. 1910 www.EllsworthCheese.com C 232 North Wallace 1858 Highway 63 O Y O R P E Ellsworth, WI Comstock, WI E R A M AT I V E C R E Welcome to Wisconsin’s All American Great River Road! dventures are awaiting you on your 250 miles of gorgeous Avistas, beaches, forests, parks, historic sites, attractions and exciting “explores.” This Travel & Visitor Guide is your trip guide to create itineraries for the most unique, one-of-a-kind experiences you can ever imagine. What is your “bliss”? What are you searching for? Peace, adventure, food & beverage destinations, connections with nature … or are your ideas and goals to take it as it comes? This is your slice of life and where you will find more than you ever dreamed is here just waiting for you, your family, friends and pets. Make memories that you will treasure forever—right here. The Wisconsin All American Great River Road curves along the Mississippi River and bluff lands through 33 amazing, historic communities in the 8 counties of this National Scenic Byway. -

The North Country Trail in the with Mineral Soil

ing a small fire. All fires should be put completely out by thor- oughly soaking the embers with water and then mixing them The North Country Trail Association is The North Country Trail in the with mineral soil. In dry conditions we suggest that you use a membership-driven, volunteer-based organization. The camp stoves rather than wood fires. In extremely dry condi- NCTA is a “friends” organization that unites the efforts of our Chequamegon-Nicolet tions open fires may be prohibited. To check on fire conditions local volunteer chapters and partner organizations with the contact the US Forest Service in that district. National Park Service to build, maintain, protect and promote the North Country National Scenic Trail. The trail is a 4,600 National Forest mile footpath through the northern tier of the United States, Parking - There is no charge for The North Country National Scenic Trail is traversing seven states. Though still under construction, more most parking areas shown on primarily a hiking trail. Horse use on the trail and more miles of trail are completed every year, the trail is the map, however, several of the is discouraged. Soils on the east end of the starting to draw national attention, alongside the likes of the more developed parking areas trail tend to be fairly wet and are not particu- Appalachian and Pacific Crest Trails. are fee areas. The following larly suitable for riding. areas require either a daily fee Mountain bikes are also discouraged and may not be ridden Our work uses federal or an annual sticker: Penokee where the trail crosses wilderness areas. -

SPRING 2021 PRESIDENT’S Report

R Falls BARRON LANGLADE Medford W Antigo Merrill i s ST. CROIX TAYLOR c Marinette DUNN CHIPPEWA o n Chippewa s MENOMINEE Wausau i n DOOR Falls OCONTO Menomonie MARATHON Sturgeon R River R Bay Eau Claire i Falls v CLARK e SHAWANO PIERCE r EAU CLAIRE G R E E N B A Y PEPIN Marshfield Green Algoma Stevens Bay Point SPRING 2021 PRESIDENT’S report to spring, a season for enjoying nature and the glorious opportunity to be outside. Whether you walk your dog, head out with your family for a day hike, or have taken on the challenge to become a Thousand-Miler, the Ice Age National Scenic Trail provides a chance for quiet recreation while following the glacial history of Wisconsin. During the past year, a record number of people discovered the Ice Age Trail, and the Alliance membership has grown to over 4,500 strong. I’m excited to welcome all our new members. 2020 was an excellent year for land acquisition, thanks to the many who contributed to our land protection efforts. It was also the year where despite COVID-19 limitations, 1,499 volunteers donated 53,297 hours as dedicated caretakers of our wonderful Trail. While some of our efforts understandably shifted during the pandemic, we continued to maintain our high standards of providing a top-notch Trail experience for all. In 2021, I invite you to join one of the small-scale Trailbuilding and Stewardship Reconnect projects available through your chapter or one of the large-scale events scheduled later this summer. -

Official List of Wisconsin's State Historic Markers

Official List of Wisconsin’s State Historical Markers Last Revised June, 2019 The Wisconsin State Historical Markers program is administered by Local History-Field Services section of the Office of Programs and Outreach. If you find a marker that has been moved, is missing or damaged, contact Janet Seymour at [email protected] Please provide the title of the marker and its current location. Each listing below includes the official marker number, the marker’s official name and location, and a map index code that corresponds to Wisconsin’s Official State Highway Map. You may download or request this year’s Official State Highway Map from the Travel W isconsin website. Markers are generally listed chronologically by the date erected. The marker numbers below jump in order, since in some cases markers have been removed for a variety of reason. For instance over time the wording of some markers has become outdated, in others historic properties being described have been moved or demolished. Number Name and Location Map Index 1. Peshtigo Fire Cemetery ................................................................................................................................5-I Peshtigo Cemetery, Oconto Ave, Peshtigo, Marinette County 2. Jefferson Prairie Settlement ........................................................................................................................11-G WI-140, 4 miles south of Clinton, Rock County 5. Shake Rag.................................................................................................................................................................10-E -

Trail Challenge Resources

Trail Challenge Resources Hiking Trails Ice Age National Scenic Trail ● Description: One of only 11 National Scenic Trails in the country, the Ice Age Trail is a 1,000-mile footpath contained entirely within the state of Wisconsin. Ancient glaciers carved the path through rocky terrain, open prairies, and peaceful forests. Now, day hikers, backpackers, and outdoor lovers of all ages rely on the Ice Age Trail for a place to unplug, relax, and enjoy nature. ● Ice Age Trail Map Interstate State Park, MN ● Description: Interstate State Park includes 293 acres of diverse plant and wildlife habitat. Established in 1895, it protects a unique landscape and globally-significant geology along the St. Croix River. A billion years ago, dark basalt rock formed here when lava escaped from a crack in the earth’s crust. Just ten thousand years ago, water from melting glaciers carved the river valley. Within that water were fast moving whirlpools of swirling sand and water that wore deep holes into the rock. Today, we call these holes glacial potholes and you can see more than 400 examples of them at the park. ● Interstate State Park Map Interstate State Park, WI ● Description: There are more than nine miles of hiking trails in the park that offer the walker many opportunities for viewing the spectacular scenery and natural attributes of the park. Guided hikes are offered during the summer months. Pets must be on a leash 8 feet or shorter at all times. Hiking trails vary in difficulty. Not all trails are surfaced; use caution on steep bluffs and near cliffs. -

April 2013 Volume 40 Number 4

APRIL 2013 VOLUME 40 NUMBER 4 Conservation Leadership Corps nterested in being a leader in con- opportunity to network with state, fed- iservation? eral and private conservation organi- Interested in having your voice zations. heard on conservation issues by Wiscon- All your expenses for involvement in sin and National policymakers? the program will be paid for by the Wis- The Wisconsin Wildlife Federation consin Wildlife Federation. At the suc- is creating a Conservation Leadership cessful completion of the program you Training Program for you! will receive a $250 scholarship to further We welcome high school students in your conservation education! their junior/senior year or freshman/ Please visit our website: www.wiwf. sophomore college students to receive org for further details. You may also con- training in conservation leadership, con- tact Leah McSherry, WWF Conservation servation policy development and how to Leadership Corps Coordinator at lmc- advocate for sound conservation policies. [email protected] or George Meyer, WWF Training will be provided by experienced Executive Director at georgemeyer@tds. conservation leaders. net with any questions or to express your Training will provide an excellent interest in the program. General Information on the Conservation Leadership Corps he Board of Directors of and presented conservation reso- didates are encouraged to attend Tthe Wisconsin Wildlife lutions may be adopted by WWF most, if not all, of these events. Federation (WWF) has to serve as official policies. All expenses encountered while initiated an exciting new program Training will be provided by participating in the CLC program to assist in the development of fu- current and former natural re- will be covered by WWF. -

Ice Age National Scenic Trail Corridor Plan and Environmental Assessment for Kewaunee, Manitowoc, and Sheboygan Counties, Wisconsin

ICE AGE NATIONAL SCENIC TRAIL CORRIDOR PLAN AND ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FOR KEWAUNEE, MANITOWOC, AND SHEBOYGAN COUNTIES, WISCONSIN Prepared by: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Bureau of Parks and Recreation National Park Service, Ice Age National Scenic Trail Ice Age Park and Trail Foundation Bay-Lake Regional Planning Commission December, 2006 PUB-PR-811 06 Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Board Gerald M. O'Brien, Chair Christine L. Thomas, Vice Chair Jonathan P. Ela, Secretary David Clausen Howard D. Poulson John W. Welter Stephen D. Willett Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Box 7921 Madison, WI 53707-7921 This publication is available in alternative format (large print, Braille, audio tape, etc.) upon request. Please call 608-266-2181 for more information. You can also view this document on the Web at: http://www.dnr.wi.gov/master_planning/ PUB-PR-811 06 Acknowledgments Lake Michigan Corridor Ice Age Trail Planning Team Lake Michigan Corridor Ice Age Trail Core Planning Team Jean Potter Ice Age Park and Trail Foundation Jeffrey Prey WDNR - Bureau of Parks and Recreation Mark Walter Bay Lake Regional Planning Commission Pam Schuler National Park Service Mary Tano National Park Service Lake Michigan Corridor Ice Age Trail Guidance / Oversight Team Peter Biermeier WDNR - Bureau of Parks and Recreation Tom Gilbert National Park Service Andrew Hanson Ice Age Park and Trail Foundation Mapping and GIS Services Tony Bellovary Bay Lake Regional Planning Commission Ice Age National Scenic Trail Corridor Plan and Environmental Assessment For Kewaunee, Manitowoc, and Sheboygan Counties, Wisconsin December, 2006 Table of Contents Executive Summary – Ice Age National Scenic Trail Corridor Plan For Kewaunee, Manitowoc, and Sheboygan Counties, Wisconsin............................................................................................. -

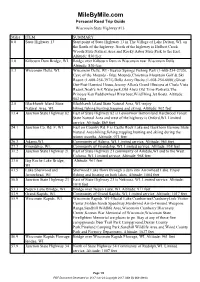

Milebymile.Com Personal Road Trip Guide Wisconsin State Highway #13

MileByMile.com Personal Road Trip Guide Wisconsin State Highway #13 Miles ITEM SUMMARY 0.0 State Highway 13 Start point of State Highway 13 in The Village of Lake Delton, WI. on the South of the highway. North of the highway is Hulbert Creek Woods State Natural Area and Rocky Arbor State Park to the East. Altitude: 830 feet 1.0 Kilbourn Dam Bridge, WI. Bridge over Kilbourn Dam in Wisconsin near Wisconsin Dells. Altitude: 830 feet 1.3 Wisconsin Dells, WI. Wisconsin Dells, WI - Beaver Springs Fishing Park (1-608-254-2735), Cave of the Mounds - Blue Mounds,Christmas Mountain Golf & Ski Resort (1-608-254-3971),Dells Army Ducks (1-608-254-6080),Ghost Out-Post Haunted House,Jeremy Allen's Grand Illusions at Chula Vista Resort,Noah's Ark Waterpark,Old Abe's Old Time Portraits,The Princess Kay Paddlewheel Riverboat,WildThing Jet Boats. Altitude: 902 feet 3.0 Blackhawk Island State Blackhawk Island State Natural Area, WI.-enjoy Natural Area, WI. hiking,fishing,hunting,trapping and skiing. Altitude: 902 feet 13.4 Junction State Highway 82 East of State Highway 82 is Lemonweir Bottomland Hardwood Forest State Natural Area and west of the highway is Oxford,WI. Limited service. Altitude: 869 feet 24.1 Junction Co. Rd. F, WI. East on Country Rd. F is Castle Rock Lake and Backhorn Barrens State Natural Area-hiking,fishing,trapping,hunting and skiing during the winter months. Altitude: 971 feet 26.3 Adams,WI. Community of Adams, WI. Limited service. Altitude: 965 feet 27.3 Friendship, WI. Community of Friendship, WI. -

High Cliff State Park Sherwood, Wisconsin

APRIL2009 VOLUME 36 NUMBER 4 NorthernDeer Herd GetHooked HealthyFollowing on the 2009 Intensive Te sting Project Wisconsin NTIGO,Wis.–Northern Wisconsin’sdeer herd has Fishing Report been given aclean bill of health. After testingmore Athan8,700 tissue samples from deer in 18 northern ADISON –Anglers look- Wisconsin counties,biologists found no signsofChronic ingfor places to fish, tips WastingDisease (CWD)orTuberculosis (TB). Mto hook their favorite The DepartmentofNatural Resourcesexceeded its goal to catch,orthe latestfishing reports for have 8,000 samples from acrossthe north thanks to coopera- the upcomingseasoncan catchthe tion from hunters,said Mike Zeckmeister,DNR Northern latestinformation in the2009 Region wildlifesupervisor. WisconsinFishing Report. TheDNR conducts periodic heath checks as adefense The 2009WisconsinFishing against seriousdiseaserisks.Being proactive is always better Report is nowavailable online. than being reactive whenitcomes to wildlife disease manage- ment, Zeckmeister explained. He added that havingaclean Thisfree,annual 16-pagenewspa- bill of health provides more justification to do everythingpos- per is an angler’s sible to keep the deer herd in northern Wisconsin freeofthese guide to the2009 seriousdiseases. fishing year, with “Unfortunately,” he said,“we arestill takingrisks withthe fishing forecasts health of our deer herdbyfeeding and baiting deer in that DepartmentofNatural Resources fish Wisconsin.” biologists provide for many popularwaters Wildlifeofficials saythe risk of spreadinginfections increas- statewide. es especiallywhere deer areartificially concentrated. Anglerslookingtotarget someof Infectious CWD prions and TB bacteria have been isolated Wisconsin’swell knownfish can dive into from deer saliva. Baitingand feeding sites foster conditions for “Hook Your FavoriteCatch” for tips on disease transfer throughincreaseddeer to deer contactand adjustingyoursights,techniquesand bait increased group sizeatfeeding sites.TBspreads from captive or domestic animals to wild deer and vice-versa.