How to Take Care of Unruly Archives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

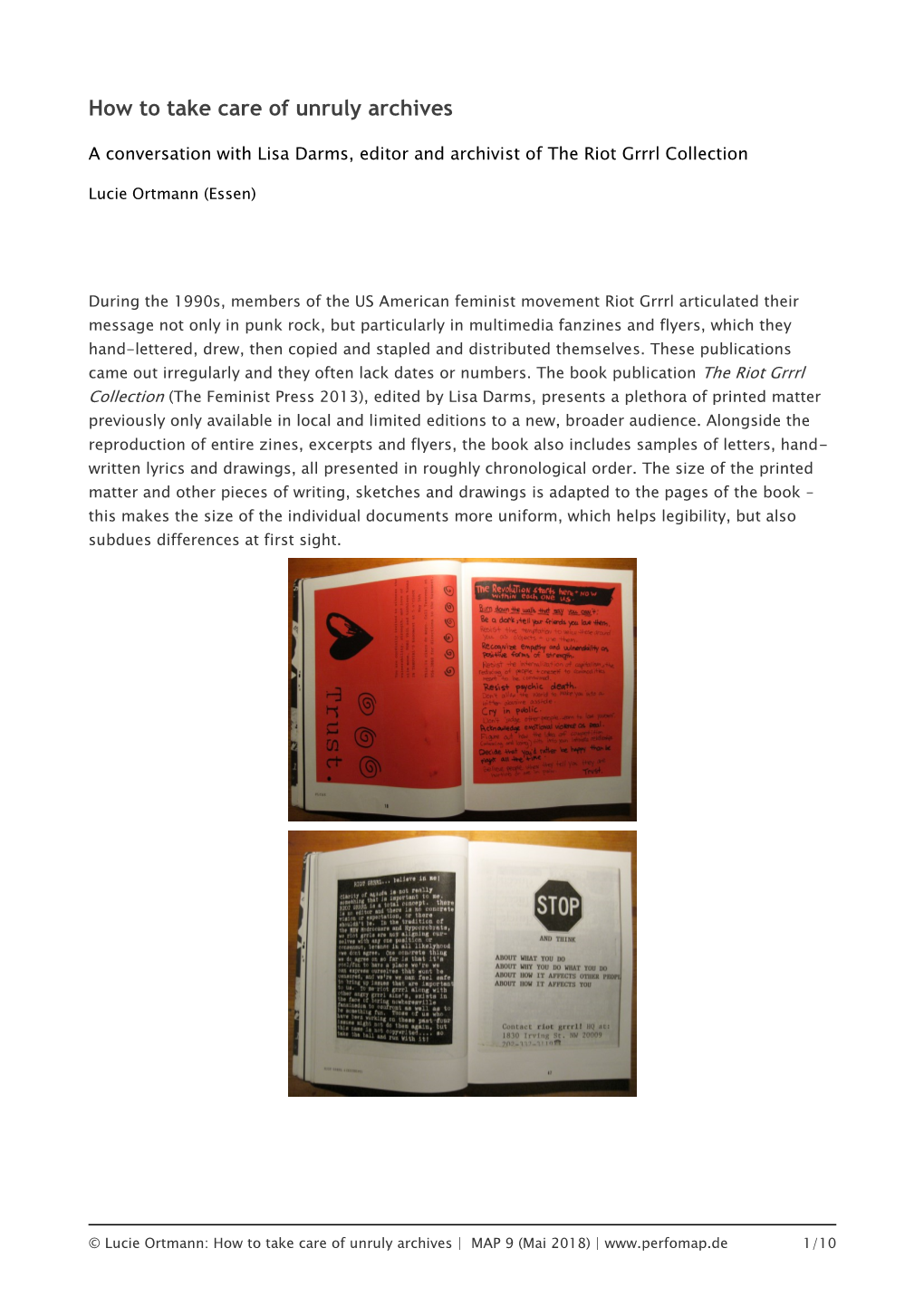

Recommended publications

-

Socially Engaged Art Project to the Curb and B.Pdf

SPRING ZINE-ING - TO THE CURB AND BEYOND JUNE 2021 OONAGH E. FITZGERALD Art Making, Sharing, Performing & Completing in the Neighbourhood as we Emerge from the Pandemic A SOCIAL ENGAGED ART PROJECT ZINES DIY self-published, independent, pamphlets, magazines, artbook, comics etc. Recent examples: skater, graffiti, Black Lives Matter Touchable, affordable, personal, raw Artists: Walter Moodie, Emmanuel Okot, Ross Le Blanc, Mikaela Kautkzy, Venise 410B, Raphael Fitzgerald-Biernath https://www.theguardian.com/music/gallery/2013/ jun/30/punk-music “riot grrrl no. 1, Molly Neuman and Allison Wolfe, July 1991. All you need to riot grrrl 1980’S - start a counter-culture revolution is a few sheets of A4 paper, a typewriter, a 90’S photocopier, a Sharpie and some old magazines. Zines were fast to produce and easy to distribute. My Life with Evan Dando, Popstar, Kathleen Hanna. In 1993, Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna created a visually raw mock-psychotic fanzine … to explore violence, objectification, misogyny and the politics of creative success… inspired in part by rage and horror at the anti-feminist [Montreal] mass … [murder]”. A VOICE FOR “Slant no. 5, Mimi Thi Ngyuen, 1996. ANYONE & riot grrrl was criticised for failing to be truly inclusive, or EVERYONE transcending its status as a predominantly white, middle-class movement. But there were riot grrrls of colour, who in classic punk style seized back the conversation on race. Zines such as Slant, Bamboo Girl, Evolution of a Race Riot and Chop Suey Spex refused the identity, as Ngyuen puts it, -

Download PDF > Riot Grrrl \\ 3Y8OTSVISUJF

LWSRQOQGSW3L / Book ~ Riot grrrl Riot grrrl Filesize: 8.18 MB Reviews Unquestionably, this is actually the very best work by any article writer. It usually does not price a lot of. Once you begin to read the book, it is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding. (Augustine Pfannerstill) DISCLAIMER | DMCA GOKP10TMWQNH / Kindle ~ Riot grrrl RIOT GRRRL To download Riot grrrl PDF, make sure you refer to the button under and download the document or gain access to other information which might be related to RIOT GRRRL book. Reference Series Books LLC Jan 2012, 2012. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 249x189x10 mm. Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 54. Chapters: Kill Rock Stars, Sleater-Kinney, Tobi Vail, Kathleen Hanna, Lucid Nation, Jessicka, Carrie Brownstein, Kids Love Lies, G. B. Jones, Sharon Cheslow, The Shondes, Jack O Jill, Not Bad for a Girl, Phranc, Bratmobile, Fih Column, Caroline Azar, Bikini Kill, Times Square, Jen Smith, Nomy Lamm, Huggy Bear, Karen Finley, Bidisha, Kaia Wilson, Emily's Sassy Lime, Mambo Taxi, The Yo-Yo Gang, Ladyfest, Bangs, Shopliing, Mecca Normal, Voodoo Queens, Sister George, Heavens to Betsy, Donna Dresch, Allison Wolfe, Billy Karren, Kathi Wilcox, Tattle Tale, Sta-Prest, All Women Are Bitches, Excuse 17, Pink Champagne, Rise Above: The Tribe 8 Documentary, Juliana Luecking, Lungleg, Rizzo, Tammy Rae Carland, The Frumpies, Lisa Rose Apramian, List of Riot Grrl bands, 36-C, Girl Germs, Cold Cold Hearts, Frightwig, Yer So Sweet, Direction, Viva Knievel. Excerpt: Riot grrrl was an underground feminist punk movement based in Washington, DC, Olympia, Washington, Portland, Oregon, and the greater Pacific Northwest which existed in the early to mid-1990s, and it is oen associated with third-wave feminism (it is sometimes seen as its starting point). -

The DIY Careers of Techno and Drum 'N' Bass Djs in Vienna

Cross-Dressing to Backbeats: The Status of the Electroclash Producer and the Politics of Electronic Music Feature Article David Madden Concordia University (Canada) Abstract Addressing the international emergence of electroclash at the turn of the millenium, this article investigates the distinct character of the genre and its related production practices, both in and out of the studio. Electroclash combines the extended pulsing sections of techno, house and other dance musics with the trashier energy of rock and new wave. The genre signals an attempt to reinvigorate dance music with a sense of sexuality, personality and irony. Electroclash also emphasizes, rather than hides, the European, trashy elements of electronic dance music. The coming together of rock and electro is examined vis-à-vis the ongoing changing sociality of music production/ distribution and the changing role of the producer. Numerous women, whether as solo producers, or in the context of collaborative groups, significantly contributed to shaping the aesthetics and production practices of electroclash, an anomaly in the history of popular music and electronic music, where the role of the producer has typically been associated with men. These changes are discussed in relation to the way electroclash producers Peaches, Le Tigre, Chicks on Speed, and Miss Kittin and the Hacker often used a hybrid approach to production that involves the integration of new(er) technologies, such as laptops containing various audio production softwares with older, inexpensive keyboards, microphones, samplers and drum machines to achieve the ironic backbeat laden hybrid electro-rock sound. Keywords: electroclash; music producers; studio production; gender; electro; electronic dance music Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 4(2): 27–47 ISSN 1947-5403 ©2011 Dancecult http://dj.dancecult.net DOI: 10.12801/1947-5403.2012.04.02.02 28 Dancecult 4(2) David Madden is a PhD Candidate (A.B.D.) in Communications at Concordia University (Montreal, QC). -

Disidentification and Evolution Within Riot Grrrl Feminism Lilly Estenson Scripps College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2012 (R)Evolution Grrrl Style Now: Disidentification and Evolution within Riot Grrrl Feminism Lilly Estenson Scripps College Recommended Citation Estenson, Lilly, "(R)Evolution Grrrl Style Now: Disidentification and Evolution within Riot Grrrl Feminism" (2012). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 94. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/94 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (R)EVOLUTION GRRRL STYLE NOW: DISIDENTIFICATION AND EVOLUTION WITHIN RIOT GRRRL FEMINISM by LILLY ESTENSON SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR CHRIS GUZAITIS PROFESSOR KIMBERLY DRAKE April 20, 2012 Estenson 1 Table of Contents Introduction ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 Chapter 1: Contextualizing Riot Grrrl Feminism ---------------------------------------- 20 Chapter 2: Feminist Praxis in the Original Riot Grrrl Movement (1990-96) ------- 48 Chapter 3: Subcultural Disidentification and Contemporary Riot Grrrl Praxis --- 72 Conclusion ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 97 Works Cited ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

'Race Riot' Within and Without 'The Grrrl One'; Ethnoracial Grrrl Zines

The ‘Race Riot’ Within and Without ‘The Grrrl One’; Ethnoracial Grrrl Zines’ Tactical Construction of Space by Addie Shrodes A thesis presented for the B. A. degree with Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Winter 2012 © March 19, 2012 Addie Cherice Shrodes Acknowledgements I wrote this thesis because of the help of many insightful and inspiring people and professors I have had the pleasure of working with during the past three years. To begin, I am immensely indebted to my thesis adviser, Prof. Gillian White, firstly for her belief in my somewhat-strange project and her continuous encouragement throughout the process of research and writing. My thesis has benefitted enormously from her insightful ideas and analysis of language, poetry and gender, among countless other topics. I also thank Prof. White for her patient and persistent work in reading every page I produced. I am very grateful to Prof. Sara Blair for inspiring and encouraging my interest in literature from my first Introduction to Literature class through my exploration of countercultural productions and theories of space. As my first English professor at Michigan and continual consultant, Prof. Blair suggested that I apply to the Honors program three years ago, and I began English Honors and wrote this particular thesis in a large part because of her. I owe a great deal to Prof. Jennifer Wenzel’s careful and helpful critique of my thesis drafts. I also thank her for her encouragement and humor when the thesis cohort weathered its most chilling deadlines. I am thankful to Prof. Lucy Hartley, Prof. -

Conceptualizing Female Punk in the Theatre: the Riot Grrrl Revolution As a Radical Force to Inspire a Devised Solo Performance Summit J

The College of Wooster Libraries Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2016 Conceptualizing Female Punk in the Theatre: The Riot Grrrl Revolution as a Radical Force to Inspire a Devised Solo Performance Summit J. Starr The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Part of the Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Starr, Summit J., "Conceptualizing Female Punk in the Theatre: The Riot Grrrl Revolution as a Radical Force to Inspire a Devised Solo Performance" (2016). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 7022. https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy/7022 This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The oC llege of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2016 Summit J. Starr The College of Wooster Conceptualizing Female Punk in the Theatre: The Riot Grrrl Revolution as a Radical Force to Inspire a Devised Solo Performance by Summit J. Starr Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Senior Independent Study Requirement Theatre and Dance 451 - 452 Advised by Jimmy A. Noriega Department of Theatre & Dance March 28th, 2016 1 | Starr Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………….………………3 Acknowledgements……………………………….………….……….……………..4 Introduction and Literature Review …………...…………………………….…….5 Chapter One: Technique and Aesthetics……...……………………….…………..18 Chapter Two: Devising Concept……………………………………….…………..31 Chapter Three: Reflection…………………………………………………………...46 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………63 Appendix A…………………………………………………………………………..65 Bibliography and Works Cited ……………………………………………………..97 2 | Starr Abstract My Independent Study focuses on the technique and aesthetic of the Riot Grrrl Revolution, and how those elements effectively continued the 90s underground punk scene. -

Allison Wolfe Interviewed by John Davis Los Angeles, California June 15, 2017 0:00:00 to 0:38:33

Allison Wolfe Interviewed by John Davis Los Angeles, California June 15, 2017 0:00:00 to 0:38:33 ________________________________________________________________________ 0:00:00 Davis: Today is June 15th, 2017. My name is John Davis. I’m the performing arts metadata archivist at the University of Maryland, speaking to Allison Wolfe. Wolfe: Are you sure it’s the 15th? Davis: Isn’t it? Yes, confirmed. Wolfe: What!? Davis: June 15th… Wolfe: OK. Davis: 2017. Wolfe: Here I am… Davis: Your plans for the rest of the day might have changed. Wolfe: [laugh] Davis: I’m doing research on fanzines, particularly D.C. fanzines. When I think of you and your connection to fanzines, I think of Girl Germs, which as far as I understand, you worked on before you moved to D.C. Is that correct? Wolfe: Yeah. I think the way I started doing fanzines was when I was living in Oregon—in Eugene, Oregon—that’s where I went to undergrad, at least for the first two years. So I went off there like 1989-’90. And I was there also the year ’90-’91. Something like that. For two years. And I met Molly Neuman in the dorms. She was my neighbor. And we later formed the band Bratmobile. But before we really had a band going, we actually started doing a fanzine. And even though I think we named the band Bratmobile as one of our earliest things, it just was a band in theory for a long time first. But we wanted to start being expressive about our opinions and having more of a voice for girls in music, or women in music, for ourselves, but also just for things that we were into. -

Rock 'N' Roll Camp for Girls and Feminist Quests for Equity, Community, and Cultural Production

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Institute for Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Theses Studies 7-31-2006 I'm Not Loud Enough to be Heard: Rock 'n' Roll Camp for Girls and Feminist Quests for Equity, Community, and Cultural Production Stacey Lynn Singer Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/wsi_theses Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Singer, Stacey Lynn, "I'm Not Loud Enough to be Heard: Rock 'n' Roll Camp for Girls and Feminist Quests for Equity, Community, and Cultural Production." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2006. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/wsi_theses/2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I’M NOT LOUD ENOUGH TO BE HEARD: ROCK ‘N’ ROLL CAMP FOR GIRLS AND FEMINIST QUESTS FOR EQUITY, COMMUNITY, AND CULTURAL PRODUCTION By STACEY LYNN SINGER Under the Direction of Susan Talburt ABSTRACT Because of what I perceive to be important contributions to female youth empowerment and the construction of culture and community, I chose to conduct a qualitative case study that explores the methods utilized in the performance of Rock ‘n’ Roll Camp for Girls, as well as the experiences of camp administrators, participants, and volunteers, in order to identify feminist constructs, aims, and outcomes of Rock ‘n’ Roll Camp for Girls. -

The Art Worlds of Punk-Inspired Feminist Networks

! The Art Worlds of Punk-Inspired Feminist Networks ! ! ! ! ! ! A social network analysis of the Ladyfest feminist music and cultural movement in the UK ! ! ! ! ! ! A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities ! ! ! 2014 ! ! Susan O’Shea ! ! School of Social Sciences ! ! Chapter One Whose music is it anyway? 1.1. Introduction 12 1.2. Ladyfest, Riot Girl and Girls Rock camps 14 1.2.1. Ladyfest 14 1.2.2. Riot Grrrl 16 1.2.3. Girls Rock camps 17 1.3. Choosing art worlds 17 1.4. The evidence: women’s participation in music 20 1.5. From the personal to the political 22 1.6. Thesis structure 25 Chapter Two The dynamics of feminist cultural production 2.1. Introduction 27 2.2. Art Worlds and Becker’s approach 29 2.3. Punk, Riot Grrrl and Ladyfest 32 2.3.1. Punk 33 2.3.2. Riot Grrrl 34 2.3.3. Ladyfest 40 2.4. The political economy of cultural production 41 2.5. Social movements, social networks and music 43 2.6. Women in music and art and the translocal nature of action 48 2.6.1. Translocality 50 2.7. Festivals as networked research sites 52 2.8. Conclusion 54 Chapter Three Methodology 3.1. Introduction 56 !2 ! 3.2. Operationalising Art Worlds, research aims and questions 57 3.3. Research philosophy 58 3.4. Concepts and terminology 63 3.5. Mixed methods 64 3.6. Ethics 66 3.6.1. Ethics review 68 3.6.2. -

The Appropriation and Packaging of Riot Grrrl Politics by Mainstream Female Musicians

Popular Music and Society, Vol. 26, No. 1, 2003 “A Little Too Ironic”: The Appropriation and Packaging of Riot Grrrl Politics by Mainstream Female Musicians Kristen Schilt “RIOT GIRL IS: BECAUSE I believe with my wholeheartmindbody that girls constitute a revolutionary soul force that can, and will, change the world for real” (“Riot Grrrl Is” 44) “Girl power!” (Spice Girls) Introduction Female rock musicians have had difficulty making it in the predominantly white male rock world. Joanne Gottlieb and Gayle Wald note that women’s participation in rock music usually consists of bolstering male performance, in the roles of groupie, girlfriend, or back-up singer (257). Even in punk rock, women are often treated as a novelty by the music press and cultural critics. Male bands such as the Sex Pistols and the Damned achieve rock notoriety while their female counterparts, like the Slits and the Raincoats, sink into obscurity. However, 1995 saw an explosion in the music press about a new group of female musicians: the angry women. Hailed in popular magazines for blending feminism and rock music, Alanis Morissette topped the charts in 1995. Affectionately named the “screech queen” by Newsweek, Morissette combined angry, sexually graphic lyrics with catchy pop music (Chang 79). She was quickly followed by Tracy Bonham, Meredith Brooks, and Fiona Apple. Though they differed in musical style, this group of musicians embodied what it meant to be a woman expressing anger through rock music, according to the music press. Popular music magazines argued that musicians like Morissette were creating a whole new genre for female performers, one that allowed them to assert their ideas about feminism and sexual- ity. -

REFORMULATING the RIOT GRRRL MOVEMENT: GRRRL RIOT the REFORMULATING : Riot Grrrl, Lyrics, Space, Sisterhood, Kathleen Hanna

REFORMULATING THE RIOT GRRRL MOVEMENT: SPACE AND SISTERHOOD IN KATHLEEN HANNA’S LYRICS Soraya Alonso Alconada Universidad del País Vasco (UPV/EHU) [email protected] Abstract Music has become a crucial domain to discuss issues such as gender, identities and equality. With this study I aim at carrying out a feminist critical discourse analysis of the lyrics by American singer and songwriter Kathleen Hanna (1968-), a pioneer within the underground punk culture and head figure of the Riot Grrrl movement. Covering relevant issues related to women’s conditions, Hanna’s lyrics put gender issues at the forefront and become a sig- nificant means to claim feminism in the underground. In this study I pay attention to the instances in which Hanna’s lyrics in Bikini Kill and Le Tigre exhibit a reading of sisterhood and space and by doing so, I will discuss women’s invisibility in underground music and broaden the social and cultural understanding of this music. Keywords: Riot Grrrl, lyrics, space, sisterhood, Kathleen Hanna. REFORMULANDO EL MOVIMIENTO RIOT GRRRL: ESPACIO Y SORORIDAD EN LAS LETRAS DE KATHLEEN HANNA Resumen 99 La música se ha convertido en un espacio en el que debatir temas como el género, la iden- tidad o la igualdad. Con este trabajo pretendo llevar a cabo un análisis crítico del discurso con perspectiva feminista de las letras de canciones de Kathleen Hanna (1968-), cantante y compositora americana, pionera del movimiento punk y figura principal del movimiento Riot Grrrl. Cubriendo temas relevantes relacionados con la condición de las mujeres, las letras de Hanna sitúan temas relacionados con el género en primera línea y se convierten en un medio significativo para reclamar el feminismo en la música underground. -

Why I Love NYC: Le Tigre

Choose your city Don't miss a thing: sign up to get the latest from Time Out. Subscribe to Time Out New York Magazine Tickets & Offers Things To Do Restaurants Bars Movies Theater Art Music Shopping & Style Blog Nightlife Attractions Events & Festivals Museums Kids Comedy Dance LGBT Sex & Dating Books City Guide Neighborhoods Hotels Promotions What When Where Things to do or see in New York All dates All areas Why I love NYC: Le Tigre The New York rockers and feminist icons share their favorite spots throughout the Hotel Belleclaire city. By Karen Iris Tucker Mon Mar 28 2011 From $197 See now The Watson Hotel From $198 See now Hotel Belleclaire The Watson Hotel From $197 From $198 Paramount Times The Lucerne Hotel Square whyiloveNYC01letigre From $278 From $217 Though its members were bred elsewhere, feminist electropunk trio Le Tigre is firmly rooted in New York City: Frontwoman Kathleen Hanna resides downtown, guitarist Johanna Fateman lives in Harlem, and keyboardist JD Samson represents Brooklyn. The band even featured an ode to the city's subway system, "My My Metrocard," on its 1999 selftitled debut album. The group has been on hiatus since 2006, but fans clamoring for a fix can relive Hanna & Co.'s frenetic live performances with the upcoming release of Who Took the Bomp? Le Tigre on Tour, directed by Kerthy Fix (Strange Powers: Stephin Merritt and the Magnetic Fields). The documentary, which is out on DVD on June 7, follows the band's 2004 tour, Millennium Broadway Hudson New York, New York Times Square and celebrates the trio's ability to lyrically pulverize homophobic bigots, Rudy Giuliani and misogynistic jerks—all while Central Park playing fun, danceable beats.