Designing a Platform That Connects People of Color to Therapists of Color

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Back Listeners: Locating Nostalgia, Domesticity and Shared Listening Practices in Contemporary Horror Podcasting

Welcome back listeners: locating nostalgia, domesticity and shared listening practices in Contemporary horror podcasting. Danielle Hancock (BA, MA) The University of East Anglia School of American Media and Arts A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2018 Contents Acknowledgements Page 2 Introduction: Why Podcasts, Why Horror, and Why Now? Pages 3-29 Section One: Remediating the Horror Podcast Pages 49-88 Case Study Part One Pages 89 -99 Section Two: The Evolution and Revival of the Audio-Horror Host. Pages 100-138 Case Study Part Two Pages 139-148 Section Three: From Imagination to Enactment: Digital Community and Collaboration in Horror Podcast Audience Cultures Pages 149-167 Case Study Part Three Pages 168-183 Section Four: Audience Presence, Collaboration and Community in Horror Podcast Theatre. Pages 184-201 Case Study Part Four Pages 202-217 Conclusion: Considering the Past and Future of Horror Podcasting Pages 218-225 Works Cited Pages 226-236 1 Acknowledgements With many thanks to Professors Richard Hand and Mark Jancovich, for their wisdom, patience and kindness in supervising this project, and to the University of East Anglia for their generous funding of this project. 2 Introduction: Why Podcasts, Why Horror, and Why Now? The origin of this thesis is, like many others before it, born from a sense of disjuncture between what I heard about something, and what I experienced of it. The ‘something’ in question is what is increasingly, and I believe somewhat erroneously, termed as ‘new audio culture’. By this I refer to all scholarly and popular talk and activity concerning iPods, MP3s, headphones, and podcasts: everything which we may understand as being tethered to an older history of audio-media, yet which is more often defined almost exclusively by its digital parameters. -

MUSIC ENGAGEMENT and MENTAL HEALTH 1 Mental Health And

MUSIC ENGAGEMENT AND MENTAL HEALTH 1 Mental Health and Music Engagement: Review, Framework, and Guidelines for Future Studies Daniel E. Gustavson, Ph.D.1,2, Peyton L. Coleman, B. S.3, John R. Iversen, Ph.D.4, Hermine H. Maes, Ph.D.5,6,7, Reyna L. Gordon2,3,8,9, and Miriam Lense, Ph.D.2,8,9 1 Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN 2 Vanderbilt Genetics Institute, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN 3 Department of Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN 4 Swartz Center for Computational Neuroscience, Institute for Neural Computation, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 5 Department of Human and Molecular Genetics, Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA 6 Department of Psychiatry, Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA 7 Massey Cancer Center, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA 8 Vanderbilt Brain Institute, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 9 The Curb Center, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN Correspondence Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Daniel Gustavson, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, 2215 Garland Ave, 511H Light Hall, Nashville, TN, 37232. E-mail: [email protected]. Phone: 615-936-2660. ORCID ID: 0000-0002-1470-4928. Conflicts of Interest The authors report no conflicts of interest MUSIC ENGAGEMENT AND MENTAL HEALTH 2 Abstract Is engaging with music good for your mental health? This question has long been the topic of empirical clinical and nonclinical investigations, with studies indicating positive associations between music engagement and quality of life, reduced depression or anxiety symptoms, and less frequent substance use. -

Written Public Comments

Written Public Comments IACC Full Committee Meeting July 16, 2010 List of Written Public Comments Jack Russell ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Todd Gastaldo .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Martha Binkley ........................................................................................................................................... 13 Marian Dar ................................................................................................................................................. 14 Bob Moffitt ................................................................................................................................................. 16 Donna Young .............................................................................................................................................. 17 Sandra Barwick ........................................................................................................................................... 20 Kerry Lane .................................................................................................................................................. 21 Katie Wright ............................................................................................................................................... 23 Matt Carey ................................................................................................................................................ -

The Effects of Music on Pain: a Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

THE EFFECTS OF MUSIC ON PAIN: A REVIEW OF SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS AND META-ANALYSIS A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Jin-Hyung Lee May, 2015 Examining Committee Members: Cheryl Dileo, Advisory Chair, Music Therapy Wendy Magee, Music Therapy Joseph Ducette, Educational Psychology Deborah Confredo, Music Education ii © Copyright 2015 By Jin-Hyung Lee All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was twofold: to critically review existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the topic of music and pain; and to systematically review and conduct a meta-analysis of clinical trials investigating the effect of music on pain encompassing a wide range of medical diagnoses, settings, age groups, and types of pain. For the review of systematic reviews, the author conducted a comprehensive search and identified 14 systematic reviews and meta-analyses. These studies were critically analyzed to present a comprehensive overview of findings, to evaluate methodological quality of the reviews, to determine issues or gaps in the literature, and to generate research questions for the following meta-analysis. For the meta-analysis, the author conducted electronic searches of 12 databases and a handsearch of related journals and reference lists of relevant systematic reviews, with partial restrictions on design (i.e., randomized controlled trials); language (i.e., English, German, Korean, and Japanese); year of publication (i.e., 1995 to 2014) and intervention (i.e., music therapy and music medicine). Analyzed studies included 87 music medicine (MM) and 10 music therapy (MT) trials; eighty-nine of the included studies involved adults and eight trials focused on children. -

Completed and Resubmitted Within the Time Frame Speci!Ed

Journal of Urban Culture Research !"#$%&'(#)*'+#$&,+ Suppakorn Disatapandhu, !"#$%$&'()&*'+,'-./*0-123+4"%-$%'5 !-'&,+)'.)/0'#1 Bussakorn Binson, !"#$%$&'()&*'+,'-./*0-123+4"%-$%'5 2.&#+.3&',.34)!-'&,+ Alan Kinear, !"#$%$&'()&*'+,'-./*0-123+4"%-$%'5 /,.&+'5%&'.6)!-'&,+ Kjell Skyllstad, ,'-./*0-12+&6+70$&3+8&*9%2 73.36'.6)!-'&,+ Pornprapit Phoasavadi, !"#$%$&'()&*'+,'-./*0-123+4"%-$%'5 !-'&,+'34)8,3+- Frances Anderson, !&$$/(/+&6+!"%*$/01&'3+,:; Bussakorn Binson, !"#$%$&'()&*'+,'-./*0-123+4"%-$%'5 Naraphong Charassri, !"#$%$&'()&*'+,'-./*0-123+4"%-$%'5 Dan Baron Cohen, <'01-1#1/+&6+4*%'06&*=%'>/?+!#$1#*/+%'5+@5#>%1-&'3+A*%B-$ Gavin Douglas, ,'-./*0-12+&6+8&*1"+!%*&$-'%3+,:; Geir Johnson, C#0->+<'6&*=%1-&'+!/'1*/+C<!D4*%'0E&0-1-&'3+8&*9%2 Zuzana Jurkova, !"%*$/0+,'-./*0-123+!B/>"+F/E#G$-> Prapon Kumjim, !"#$%$&'()&*'+,'-./*0-123+4"%-$%'5 Le Van Toan,+8%1-&'%$+;>%5/=2+&6+C#0->3+H-/1'%= Shin Nakagawa, 70%)%+!-12+,'-./*0-123+I%E%' Svanibor Pettan, ,'-./*0-12+&6+JK#G$K%'%3+:$&./'-% Leon Stefanija,+,'-./*0-12+&6+JK#G$K%'%3+:$&./'-% Deborah Stevenson,+,'-./*0-12+&6+L/01/*'+:25'/23+;#01*%$-% Pornsanong Vongsingthong, !"#$%$&'()&*'+,'-./*0-123+4"%-$%'5 9#5:3;&#+ Alan Kinear <3=,%&)>)*#;'6. Alan Kinear3+!&./*+G2 Nawarat Sitthimongkolchai /,?=+'60& It is a condition of publication that the Journal assigns copyright or licenses the publication rights in their articles, including abstracts, to the authors. /,.&3$&)2.1,+:3&',.@ Journal of Urban Culture Research Faculty of Fine and Applied Arts Chulalongkorn University Payathai Road, Pathumwan Bangkok, Thailand 10330 Voice/Fax: 662-218-4582 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cujucr.com This publication is a non-pro!t educational research journal not for sale. -

Sound Therapy in Children

REVIEW ARTICLE HONG KONG JOURNAL OF PAEDIATRICS RESEARCH Hong Kong J Pediatr Res 20 2 1 ; 4 ( 1 ): 1 - 5 ISSN (e): 2663-5887 ISSN(p): 2663-7987 Sound therapy in children Sukhbir K Shahid1 1 Consultant Pediatrician and Neonatologist, Mumbai, India *Corresponding Author: Dr. Sukhbir K. Shahid, Consultant Pediatrician and Neonatologist, Shahid Clinic, Ghatkopar (East), Mumbai-400 077. MH. India. Phone: 0091-9869036606, Email: [email protected] Abstract Sound remains largely under-evaluated in the field of therapeutic medicine. It produces the desired changes both by the sound as well as the vibrational energy. Various modes have been used to deliver the energy to the individual. But studies on use of sound therapy in adults and children are limited and of poor design. In children, it has been tested in various conditions such as autism, developmental delays, in neonatal intensive care units on preterm babies, during MRI to lessen the anxiety and use of GA and sedatives, in ADHD, in pediatric cardiac care units, in childhood asthma, in emergency room patients, in chronic pain, neurological disabilities, and in troubled adolescents with substance abuse or neurotic disorders. The outcomes have been generally positive. But more large-scale and properly-designed comparative studies would be required before the low cost technology and safe sound therapy could be incorporated in the therapeutic armamentarium in children. Keywords: Children, Pediatric care, Sound therapy. respectively [4]. Thus sound is an oscillation and is propagated INTRODUCTION as a wave motion in an elastic media or air. It vibrates the media and the latter shows pressure, particle displacement, and Sound is a vibroacoustic wave with diagnostic and therapeutic velocity variations. -

Epistemology and Psychotherapists: Clarifying the Link Among Epistemic Style, Experience, and Therapist Characteristics

EPISTEMOLOGY AND PSYCHOTHERAPISTS: CLARIFYING THE LINK AMONG EPISTEMIC STYLE, EXPERIENCE, AND THERAPIST CHARACTERISTICS By GIZEM AKSOY A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2005 Copyright 2005 by Gizem Aksoy ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisor and committee chair, Dr. Greg J. Neimeyer, my beloved husband, Ferit Toska, and my dear friend Burhan Öğüt for their extensive guidance, support and encouragement. I am thankful for the assistance given to me by my committee members, Dr. Kenneth Rice and Dr. Michael Farrar. I am grateful to my family and my friends in Turkey and in Gainesville for their love and support. I could not have done this project without their help. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................. iii LIST OF TABLES............................................................................................................. vi ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................... vii CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................1 Epistemic Style .............................................................................................................2 Personal Epistemology and Personal Qualities ............................................................4 -

Controlling Acute Post-Operative Pain in Iranian Children with Using of Music Therapy Mojtaba Miladinia1, *Shahram Baraz1, Kourosh Zarea11

http:// ijp.mums.ac.ir Original Article (Pages: 1725-1730) Controlling Acute Post-operative Pain in Iranian Children with using of Music Therapy Mojtaba Miladinia1, *Shahram Baraz1, Kourosh Zarea11 1Nursing Care Research Center in Chronic Diseases, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, I.R Iran. Abstract Background: Despite the development of pediatric post-operative pain management and use of analgesic/narcotic drugs, post-operative pain remains as a common problem. Some studies suggested, the most effective approach to controlling immediate post-operative pain may include a combination of drug agents and non-drug methods. The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of music therapy on the acute post-operative pain in Iranian children. Materials and Methods: A quasi-experimental, repeated measure design was used. In this study, 63 children were placed in the music and control groups. In the music group, pain intensity was measured before start intervention (baseline). Then, this group listened to two non-speech music for 20 minutes. Then, pain intensity was measured with numeric rating scale, immediately after intervention, 1 hour, 3 hours and 6 hours after intervention, respectively. Also, in the control group, pain intensity was measured in times similar to music group. Results: The mean of pain intensity did not significantly different between the 2 groups at baseline (P>0.05). The results of repeated measure ANOVA showed that, trend of pain intensity between 2 groups was significant (P<0.05), so that pain intensity in the music group had more decrease than control group. -

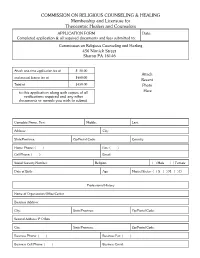

B:\Archives 03 16 04\Other Documents Or Files\C-101

COMMISSION ON RELIGIOUS COUNSELING & HEALING Membership and Licensure for Theocentric Healers and Counselors APPLICATION FORM Date: Completed application & all required documents and fees submitted to: Commission on Religious Counseling and Healing Attach one-time application fee of $ 50.00 Attach and annual license fee of $ 0.00 40 Recent Total of $450.00 Photo to this application along with copies of all Here verifications required and any other documents or awards you wish to submit. Complete Name, First: Middle: Last: Address: City: State/Province: Zip/Postal Code: Country: Home Phone: ( ) Fax: ( ) Cell Phone: ( ) Email: Social Security Number: Religion: ( ) Male ( ) Female Date of Birth: Age: Marital Status: ( ) S ( ) M ( ) D Professional History Name of Organization/Office/Center Business Address: City: State/Province: Zip/Postal Code: Second Address/ P O Box City: State/Province: Zip/Postal Code: Business Phone: ( ) Business Fax: ( ) Business Cell Phone: ( ) Business Email: Type of Practice: Describe Therapies/Services Used: Number of Years in Practice: Number of Clients: Academic History Name of School Years Attended Diploma Received Date Graduated Have you ever been investigated by a lawful authority or arrested for any crime against another person? ( ) Yes ( ) No If “Yes” , explain: Registration of Services for Licensure Please check all applicable services offered by you in your practice that you have been trained to do. The Commission will review these. Those that fall under our canonical parameters will be included under the license issued to you. Those not under out canonical paramentes will be addressed in a separate letter in order to resolve the issue(s) pending. If the service you offer is not listed below, you may add under “other”. -

Music Medicine and Music Therapy in Austria

Music Medicine and Music Therapy in Austria T#+3)8+3.-#;b)U30+3)J360'3.bb)3.-)/43%-'3)P';$0#+bbb)HA%;&+'3I A5;&+3$& The purpose of this paper is to focus on the social vulnerability of slum residents in times of disaster and to consider the possibilities of self-empowerment by the cultivation of “actual abilities” through theater workshops. The author has fo- cused on the Nang Loeng Community, occupying an urban slum in Bangkok, and with the cooperation of a Japanese theater company, has carried out a four-day theater workshop for elementary school students in the name of an “evacuation drill.” Interviews and questionnaires were conducted to the residents and partici- pants to examine the possibilities of adopting this method in the community. It was found that, in order to utilize theater workshops for self-empowerment, there is a need to investigate concrete means of improving the living environment and solving family discord, as well as a necessity to consider the possibilities of social participation through bottom-up discussions. R#=G,+-;@):&>-%$+<'>$#0-&'3+;*10+C%'%(/=/'13+4"/%1/*+L&*)0"&E3+,*G%'+:$#=3+ :/$6D@=E&9/*=/'13+8%'(+J&/'(+!&==#'-12 b Vera Brandes, Director of the Research Program for Music Medicine at Paracelsus Medical University, Salzburg, Austria and vice president of IAMM (International Association for Music and Medicine), Waehringer Strasse 115/19 1180, Vienna, Austria. voice: + 0043 664-255-0102, email: [email protected] bb) Zahra Taghian, certi!ed clinical and health psychologist and a psychologist in the Research Program for Music- Medicine at Paracelsus Medical University, Salzburg, Austria bbb)Claudia Fischer, music psychologist and head psychologist at the Research Program for Music Medicine at Paracel- sus Medical University, Salzburg, Austria 7%;'$)7#-'$'.#)3.-)7%;'$)J0#+3?=)'.)A%;&+'3) c))ih 2.&+,-%$&',. -

Effect of Spiritual Cognitive Therapy on Decreasing the Depression Level Among Elderly at Nursing Home

International Journal of Nursing and Health Services (IJNHS) http://ijnhs.net/index.php/ijnhs/home Volume 3 Issue 3, June 20th 2020, pp 418-423 e-ISSN: 2654-6310 Effect of Spiritual Cognitive Therapy on Decreasing the Depression Level among Elderly at Nursing Home Ratna Sari Rumakey1*, Retno Indarwati2, Merryana Andriani3 1Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya Indonesia 2Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya Indonesia 3Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya Indonesia Article info Abstract. Depression in the elderly with age> 65 can cause Article history: dysfunction in everyday life, older people with depression have a Received; July 15th, 2019 worse function than the elderly with chronic conditions. This study Revised: August 04th, 2019 aims to identify the effect of cognitive, spiritual therapy on Accepted: September 09th, decreasing depression in the elderly in nursing homes. A quasi- 2019 experimental pre and post-test with an equivalent control group were applied in this study. Sixty-one older people were selected in this study using a simple random sampling technique. The results Correspondence author: showed there was a significant influence of spiritual, cognitive Ratna Sari Rumakey therapy on depression (p=0.000). In conclusion, spiritual, cognitive E-mail: ratnas.sari.rumakey- therapy affects reducing depression in the elderly [email protected] Keyword: spiritual, cognitive therapy, depression, elderly DOI: 10.35654/ijnhs.v3i3.245 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License CC BY -4.0 INTRODUCTION Depression in the elderly with age ≥65 can cause dysfunction in daily life, the elderly with depression have a worse function compared to the elderly with chronic pain conditions (1). -

Video Rental Catalog 2008:Layout 1

National Guild of Hypnotists, Inc. VViiddeeoo RReennttaall CCaattaalloogg 22000088 P.O. Box 308 • Merrimack, NH 03054-0308 (603) 429-9438 • FAX (603) 424-8066 • Email [email protected] National Guild of Hypnotists, Inc. Video Rental Policies and Procedures • Video rentals are available only to NGH members in good standing in the continental United States or Canada. • There is a maximum of six titles per order. • Seminar videos with a running time of approximately 50 minutes are available to rent for $5.00 each plus postage and handling. • Video numbers ending in W are workshops, with a longer running time of 90-180 minutes. Workshops are avail- able to rent for $10.00 each plus postage and handling (see below). • Video rental rates are for a three-week period determined by postmarks from our office and date the videos are returned to us. There will be a late charge of $0.75 per day, per tape ($1.00 per day for a workshop set of 2 tapes) kept longer than the 3-week period. Please return videos on time, since there is usually someone else waiting. • A return address label and pre-posted envelope are included with each order within the United States. For orders to Canada, return postage is not included and it is the member’s responsibility to post the return. • Our normal procedure is to ship Priority Mail within the United States. • It is necessary to have a credit card number and authorization (or a $20 deposit) on file to cover late or non-return fees. • In the event that a video is held for 30 days without notification to our office, the full purchase price will be charged to you.