0204 074Turner.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PLANT COMMUNITY FIELD GUIDE Introduction to Rainforest

PLANT COMMUNITY FIELD GUIDE Introduction to Rainforest Communities Table of Contents (click to go to page) HCCREMS Mapping ....................................................................... 3 Field Data Sheet ............................................................................. 4 Which of the following descriptions best describes your site? ................................................................ 5 Which plant community is it? .......................................................... 9 Rainforest communities of the Lower Hunter .................................. 11 Common Rainforest Species of the Lower Hunter ........................................................................ 14 A picture guide to common rainforest species of the Lower Hunter ........................................................... 17 Weeding of Rainforest Remnants ................................................... 25 Rainforest Regeneration near Black Jacks Point ............................ 27 Protection of Rainforest Remnants in the Lower Hunter & the Re-establishment of Diverse, Indigenous Plant Communities ... 28 Guidelines for a rainforest remnant planting program ..................... 31 Threatened Species ....................................................................... 36 References ..................................................................................... 43 Acknowledgements......................................................................... 43 Image Credits ................................................................................ -

Fig Parrot Husbandry

Made available at http://www.aszk.org.au/Husbandry%20Manuals.htm with permission of the author AVIAN HUSBANDRY NOTES FIG PARROTS MACLEAY’S FIG PARROT Cyclopsitta diopthalma macleayana BAND SIZE AND SPECIAL BANDING REQUIREMENTS - Band size 3/16” - Donna Corporation Band Bands must be metal as fig parrots are vigorous chewers and will destroy bands made of softer material. SEXING METHODS - Fig Parrots can be sexed visually, when mature (approximately 1 year). Males - Lower cheeks and centre of forehead red; remainder of facial area blue, darker on sides of forehead, paler and more greenish around eyes. Females - General plumage duller and more yellowish than male; centre of forehead red; lower cheeks buff - brown with bluish markings; larger size (Forshaw,1992). ADULT WEIGHTS AND MEASUREMENTS - Male - Wing: 83-90 mm Tail : 34-45 mm Exp. cul: 13-14 mm Tars: 13-14 mm Weight : 39-43 g Female - Wing: 79-89 mm Tail: 34-45 mm Exp.cul: 13-14 mm Tars: 13-14 mm Weight : 39-43 g (Crome & Shield, 1992) Orange-breasted Fig Parrot Cyclopsitta gulielmitertii Edwards Fig Parrot Psittaculirostris edwardsii Salvadori’s Fig Parrot Psittaculirostris salvadorii Desmarest Fig Parrot Psittaculirostris desmarestii Fig Parrot Husbandry Manual – Draft September2000 Compiled by Liz Romer 1 Made available at http://www.aszk.org.au/Husbandry%20Manuals.htm with permission of the author NATURAL HISTORY Macleay’s Fig Parrot 1.0 DISTRIBUTION Macleay’s Fig Parrot inhabits coastal and contiguous mountain rainforests of north - eastern Queensland, from Mount Amos, near Cooktown, south to Cardwell, and possibly the Seaview Range. This subspecies is particularly common in the Atherton Tableland region and near Cairns where it visits fig trees in and around the town to feed during the breeding season (Forshaw,1992). -

Ficus Rubiginosa 1 (X /2)

KEY TO GROUP 4 Plants with a milky white sap present – latex. Although not all are poisonous, all should be treated with caution, at least initially. (May need to squeeze the broken end of the stem or petiole). The plants in this group belong to the Apocynaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Moraceae, and Sapotaceae. Although an occasional vine in the Convolvulaceae which, has some watery/milky sap will key to here, please refer to Group 3. (3.I, 3.J, 3.K) A. leaves B. leaves C. leaves alternate opposite whorled 1 Leaves alternate on the twigs (see sketch A), usually shrubs and 2 trees, occasionally a woody vine or scrambler go to Group 4.A 1* Leaves opposite (B) or whorled (C), i.e., more than 2 arising at the same level on the twigs go to 2 2 Herbs usually less than 60 cm tall go to Group 4.B 2* Shrubs or trees usually taller than 1 m go to Group 4.C 1 (All Apocynaceae) Ficus obliqua 1 (x /2) Ficus rubiginosa 1 (x /2) 2 GROUP 4.A Leaves alternate, shrubs or trees, occasional vine (chiefly Moraceae, Sapotaceae). Ficus spp. (Moraceae) Ficus, the Latin word for the edible fig. About 9 species have been recorded for the Island. Most, unless cultivated, will be found only in the dry rainforest areas or closed forest, as in Nelly Bay. They are distinguished by the latex which flows from all broken portions; the alternate usually leathery leaves; the prominent stipule (↑) which encloses the terminal bud and the “fig” (↑) or syconia. This fleshy receptacle bears the flowers on the inside; as the seeds mature the receptacle enlarges and often softens (Think of the edible fig!). -

EPBC Protected Matters Database Search Results

FLORA AND FAUNA TECHNICAL REPORT Gold Coast Quarry EIS ATTACHMENT A – EPBC Protected Matters Database Search Results April 2013 Cardno Chenoweth 71 EPBC Act Protected Matters Report This report provides general guidance on matters of national environmental significance and other matters protected by the EPBC Act in the area you have selected. Information on the coverage of this report and qualifications on data supporting this report are contained in the caveat at the end of the report. Information about the EPBC Act including significance guidelines, forms and application process details can be found at http://www.environment.gov.au/epbc/assessmentsapprovals/index.html Report created: 01/06/12 14:33:07 Summary Details Matters of NES Other Matters Protected by the EPBC Act Extra Information Caveat Acknowledgements This map may contain data which are ©Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia), ©PSMA 2010 Coordinates Buffer: 6.0Km Summary Matters of National Environment Significance This part of the report summarises the matters of national environmental significance that may occur in, or may relate to, the area you nominated. Further information is available in the detail part of the report, which can be accessed by scrolling or following the links below. If you are proposing to undertake an activity that may have a significant impact on one or more matters of national environmental significance then you should consider the Administrative Guidelines on Significance - see http://www.environment.gov.au/epbc/assessmentsapprovals/guidelines/index.html World Heritage Properties: None National Heritage Places: None Wetlands of International 1 Great Barrier Reef Marine Park: None Commonwealth Marine Areas: None Threatened Ecological Communities: 1 Threatened Species: 57 Migratory Species: 27 Other Matters Protected by the EPBC Act This part of the report summarises other matters protected under the Act that may relate to the area you nominated. -

Flying Foxes Jerry Copy

Species Common Name Habit Flowering Fruit Notes Acacia macradenia Zigzag wattle Shrub August Possible pollen source Albizia lebbek Lebbek Tall tree summer Source of nectar. Excellent shade tree for large gardens. Alphitonia excelsa Red ash Tree October to March November to May Food source for Black and Grey- headed flying fox Angophora costata Smooth-barked Tall tree December to Source of nectar apple January Angophora Rough-barked apple Tall tree September to Source of nectar floribunda February Angophora costata Smooth-barked Tall tree November to Source of nectar subsp. leiocarpa apple, Rusty gum February Archontophoenix Alexander palm Tree-like November to January Food source for alexandrae December Spectacled flying fox. Good garden tree Archontophoenix Bangalow palm Tree-like February to June March to July Food source for cunninghamiana Grey-headed flying fox. Good garden tree Species Common Name Habit Flowering Fruit Notes Banksia integrifolia Coastal Shrub or small tree Recurrent, all year Food source for honeysuckle round Black and Grey- headed flying fox. Good garden tree Banksia serrata Old man banksia Shrub or small tree February to May Source of nectar. Good garden tree Buckinghamia Ivory curl tree Small tree December to Possible source of celsissima February nectar. Good garden tree Callistemon citrinus Crimson bottlebrush Shrub or small tree November and Source of nectar. March Good garden tree Callistemon salignus White bottlebrush Shrub or small tree spring Source of nectar. Good garden tree Castanospermum Moreton Bay Tall tree spring Source of nectar australe chestnut, Black bean Corymbia citriodora Lemon-scented gum Tall tree may flower in any Source of nectar season Corymbia Red bloodwood From mallee to tall summer to autumn Source of nectar gummifera tree Corymbia Pink bloodwood Tall tree December to March Source of nectar. -

Pollinated by Pleistodontes Imperialis. (Ficus Carica); Most

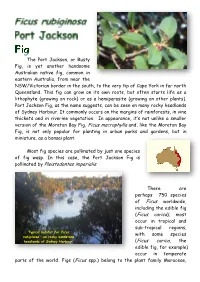

The Port Jackson, or Rusty Fig, is yet another handsome Australian native fig, common in eastern Australia, from near the NSW/Victorian border in the south, to the very tip of Cape York in far north Queensland. This fig can grow on its own roots, but often starts life as a lithophyte (growing on rock) or as a hemiparasite (growing on other plants). Port Jackson Fig, as the name suggests, can be seen on many rocky headlands of Sydney Harbour. It commonly occurs on the margins of rainforests, in vine thickets and in riverine vegetation. In appearance, it’s not unlike a smaller version of the Moreton Bay Fig, Ficus macrophylla and, like the Moreton Bay Fig, is not only popular for planting in urban parks and gardens, but in miniature, as a bonsai plant. Most fig species are pollinated by just one species of fig wasp. In this case, the Port Jackson Fig is pollinated by Pleistodontes imperialis. There are perhaps 750 species of Ficus worldwide, including the edible fig (Ficus carica); most occur in tropical and sub-tropical regions, Typical habitat for Ficus with some species rubiginosa – on rocky sandstone headlands of Sydney Harbour. (Ficus carica, the edible fig, for example) occur in temperate parts of the world. Figs (Ficus spp.) belong to the plant family Moraceae, which also includes Mulberries (Morus spp.), Breadfruit and Jackfruit (Artocarpus spp.). Think of a mulberry, and imagine it turned inside out. This might perhaps bear some resemblance to a fig. Ficus rubiginosa growing on a sandstone platform adjoining mangroves. Branches of one can be seen in the foreground, a larger one at the rear. -

Spring Bird Surveys in the Gloucester Tops

Gloucester Tops bird surveys The Whistler 13 (2019): 26-34 Spring bird surveys in the Gloucester Tops Alan Stuart1 and Mike Newman2 181 Queens Road, New Lambton, NSW 2305, Australia [email protected] 272 Axiom Way, Acton Park, Tasmania 7021, Australia [email protected] Received 14 March 2019; accepted 11 May 2019; published on-line 15 July 2019 Spring surveys between 2010 and 2017 in the Gloucester Tops in New South Wales recorded 92 bird species. The bird assemblages in three altitude zones were characterised and the Reporting Rates for individual species were compared. Five species (Rufous Scrub-bird Atrichornis rufescens, Red-browed Treecreeper Climacteris erythrops, Crescent Honeyeater Phylidonyris pyrrhopterus, Olive Whistler Pachycephala olivacea and Flame Robin Petroica phoenicea) were more likely to be recorded at high altitude. The Sulphur-crested Cockatoo Cacatua galerita, Brown Cuckoo-Dove Macropygia phasianella and Wonga Pigeon Leucosarcia melanoleuca were less likely to be recorded at high altitude. All these differences were statistically significant. Two species, Paradise Riflebird Lophorina paradiseus and Bell Miner Manorina melanophrys, were more likely to be recorded at mid-altitude than at high altitude, and had no low-altitude records. The differences were statistically significant. Many of the 78 species found at low altitude were infrequently or never recorded at higher altitudes and for 18 species, the differences warrant further investigation. There was only one record of the Regent Bowerbird Sericulus chrysocephalus and evidence is provided that this species may have become uncommon in the area. The populations of Green Catbird Ailuroedus crassirostris, Australian Logrunner Orthonyx temminckii and Pale-yellow Robin Tregellasia capito may also have declined. -

Ficus Rubiginosa F. Rubiginosa Click on Images to Enlarge

Species information Abo ut Reso urces Hom e A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Ficus rubiginosa f. rubiginosa Click on images to enlarge Family Moraceae Scientific Name Ficus rubiginosa Desf. ex Vent. f. rubiginosa Ventenat, E.P. (1805) Jard. Malm. : 114. Type: New Holland; holo: FI. Fide Dixon et al. (2001). Leaves and figs. Copyright G. Sankowsky Common name Fig; Small-leaved Fig; Larger Small-leaved Fig; Larger Small Leaf Fig; Fig, Larger Small Leaf; Fig, Small-leaved Stem A strangling fig, hemi-epiphyte or lithophyte to 30 m. Leaves Figs. Copyright G. Sankowsky Petioles and twigs produce a milky exudate. Stipules about 2-6 cm long, usually smooth on the outer surface, occasionally hairy. Petioles to 4 cm long, channelled on the upper surface. Leaf blades rather variable in shape, about 6-10 x 2-3 cm; leaves hairy. Flowers Tepals glabrous. Male flowers dispersed among the fruitlets in the ripe figs. Anthers reniform. Stigma cylindric, papillose, often slightly coiled. Bracts at the base of the fig, two. Lateral bracts not present on the outside of the fig body. Fruit Scale bar 10mm. Copyright CSIRO Figs pedunculate, globose, about 10-18 mm diam. Orifice triradiate, +/- closed by inflexed internal bracts. Seedlings Cotyledons ovate-oblong, about 5 mm long. At the tenth leaf stage: leaves ovate, apex acute or bluntly acute, base obtuse or cordate, margin entire, glabrous, somewhat triplinerved at the base; oil dots not visible; stipules large, sheathing the terminal bud, about 20-40 mm long. -

![12 Laman St Figs Report 280910[1] Mckenzie](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3219/12-laman-st-figs-report-280910-1-mckenzie-1293219.webp)

12 Laman St Figs Report 280910[1] Mckenzie

Expert Witness Report Parks and Playgrounds Movement Inc v Newcastle City Council [2010] NSWLEC 40745 Laman Street, Cooks Hill (between Dawson Street and Darby Street) Prepared for Parks and Playgrounds Movement Inc (Contact: Mr Doug Lithgow, President) Prepared by Ian McKenzie – Consulting Arborist 28 September 2010 Table of Contents 1 Summary.....................................................................................................2 2 Introduction ................................................................................................4 2.1 Acknowledgement ................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Disclaimer ................................................................................................................ 4 2.3 Background .............................................................................................................. 4 2.4 Brief ......................................................................................................................... 5 2.5 Methodology ............................................................................................................ 6 3 Site Details..................................................................................................7 3.1 Site Description........................................................................................................ 7 3.2 Heritage Status ........................................................................................................ -

(ASNSW) the Moreton Bay and Port Jackson Fig Trees

The Avicultural Society of New South Wales Inc. (ASNSW) (Founded in 1940 as the Parrot & African Lovebird Society of Australia) The Moreton Bay and Port Jackson Fig Trees (Bird) Plant of the Month (ASNSW Meeting - May 2012) By Janet Macpherson Moreton Bay Fig (Ficus macrophylla) Moreton Bay Fig (Ficus macrophylla) Both the Moreton Bay (Ficus macrophylla) and the Port Jackson (Ficus rubiginosa ) are rainforest trees which are native to the eastern coast of Australia. We have one of each of these trees growing in our garden at present. The first, the Moreton Bay Fig, was germinated from the seeds from the mature Moreton Bay Fig trees growing in Hyde Park in the city of Sydney. I picked up the fruit from under the trees over 35 years ago now. I initially managed to cultivate two trees from this seed. However, I kept the trees in pots too long and ended up with just the one. Living on acreage I planted the tree down on a lower slope in the garden where it still stands today not yet fully grown. I was thinking at the time that I planted it that it would live and grow untouched for at least as long as I live here and hopefully for many years following. We are all aware of just how long most trees will live in the right conditions and thought this tree too had the opportunity to live and grow and provide shelter and food for our native birds for a very long time. I am now uncertain of its longevity however, as neighbours of more recent years have put in a large water storage facility not too far from where the tree stands. -

Atoll Research Bulletin No. 350 Pisonia Islands of the Great Barrier Reef

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 350 PISONIA ISLANDS OF THE GREAT BARRIER REEF PART I. THE DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE AND DISPERSAL BY SEABIRDS OF PISONIA GRANDIS BY T. A. WALKER PISONIA ISLANDS OF THE GREAT BARRIER REEF PARTII. THE VASCULAR FLORAS OF BUSHY AND REDBILL ISLANDS BY T. A. WALKER, M.Y. CHALOUPKA, AND B. R KING. PISONIA ISLANDS OF THE GREAT BARRIER REEF PART 111. CHANGES IN THE VASCULAR FLORA OF LADY MUSGRAVE ISLAND BY T. A. WALKER ISSUED BY NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION WASHINGTON D.C., U.S.A. JULY 1991 (60 mme gauge) (104 mwe peak) Figure 1-1. The Great Barrier Reef showing localities referred to in the text. Mean monthly rainfall data is illustrated for the four cays and the four rocky islands where records are available. Sizes of the ten largest cays on the Great Barrier Reef are shown below - three at the southern end (23 -24s) and seven at the northern end (9-11s). 4m - SEA LidIsland 14 years (1973-1986) 'J . armual mean 15% mm 1m annual median 1459 mm O ' ONDMJJAS (10 metre gauge) "A (341 mme peak) Low Islet 97 yeam (1887-1984) annualmeana080mm 100 . annual median 2038 mm $> .:+.:.:. n8 m 100 Pine Islet 52 yeus (1934-1986) &al mean 878 mm. malmedm 814 mm (58 mwe hgh puge. 68 mem iddpeak) O ONDJFIVlnJJAS MO Nonh Reef Island l6years (1961-1977) mual mean 1067 mm. mmlmedian 1013 mm O ONDMJJAS MO Haon Island 26 years (19561982) annual mean 1039 mm,mal median 1026 mm Lady Elliot Island 47 yeus (1539-1986) annual mean 1177 mm, ma1median 1149 mm O ONDMJJAS PISONIA ISLANDS OF THE GREAT BARRIER REEF PART I. -

Ficus Obliqua G.Forst

Australian Tropical Rainforest Plants - Online edition Ficus obliqua G.Forst. Family: Moraceae Forster, J.G. (1786) Florulae Insularum Australium Prodromus : 77. Type: Vanuatu, Namoka, Tanna Island, G. Forster. Fide Dixon et al. (2001). Common name: Small Leaved Fig; Small-leafed Fig; Small Leaf Fig; Fig, Small-leafed; Fig, Small Leaved; Fig, Small Leaf; Fig; Figwood Stem A strangling fig. Exudate copious. Leaves Leaves and figs. © CSIRO Leaf blades small, about 5-12 x 1.5-5 cm. Leaf bearing twigs slender, about 1.5-3 mm diam. Stipules 1.5-3 cm long. Petioles about 1-1.5 cm long, channelled on the upper surface. Flowers Tepals glabrous. Male flowers dispersed among the fruitlets of the ripe figs. Anthers reniform. Stigma cylindric, papillose often slightly coiled. Bracts at the base of the fig, two. Lateral bracts not present on the outside of the fig body. Fruit Figs shortly pedunculate, globose, about 6-10 mm diam. Orifice triradiate, +/- closed by inflexed internal bracts. Seedlings Scale bar 10mm. © CSIRO Cotyledons +/- orbicular, about 2-4 mm diam., apex emarginate with a small gland (visible with a lens) in the notch. A few 'oil dots' visible with a lens. First pair of leaves toothed. At the tenth leaf stage: leaf blade lanceolate, margins usually entire, glabrous; oil dots not visible; petiole and stem glabrous; stipules large, sheathing the terminal bud, narrowly triangular, about 10-30 mm long, glabrous. Taproot swollen, carrot-like (Daucus carota). Seed germination time 11 to 28 days. Distribution and Ecology Occurs in CYP, NEQ, CEQ and southwards as far as south-eastern New South Wales.