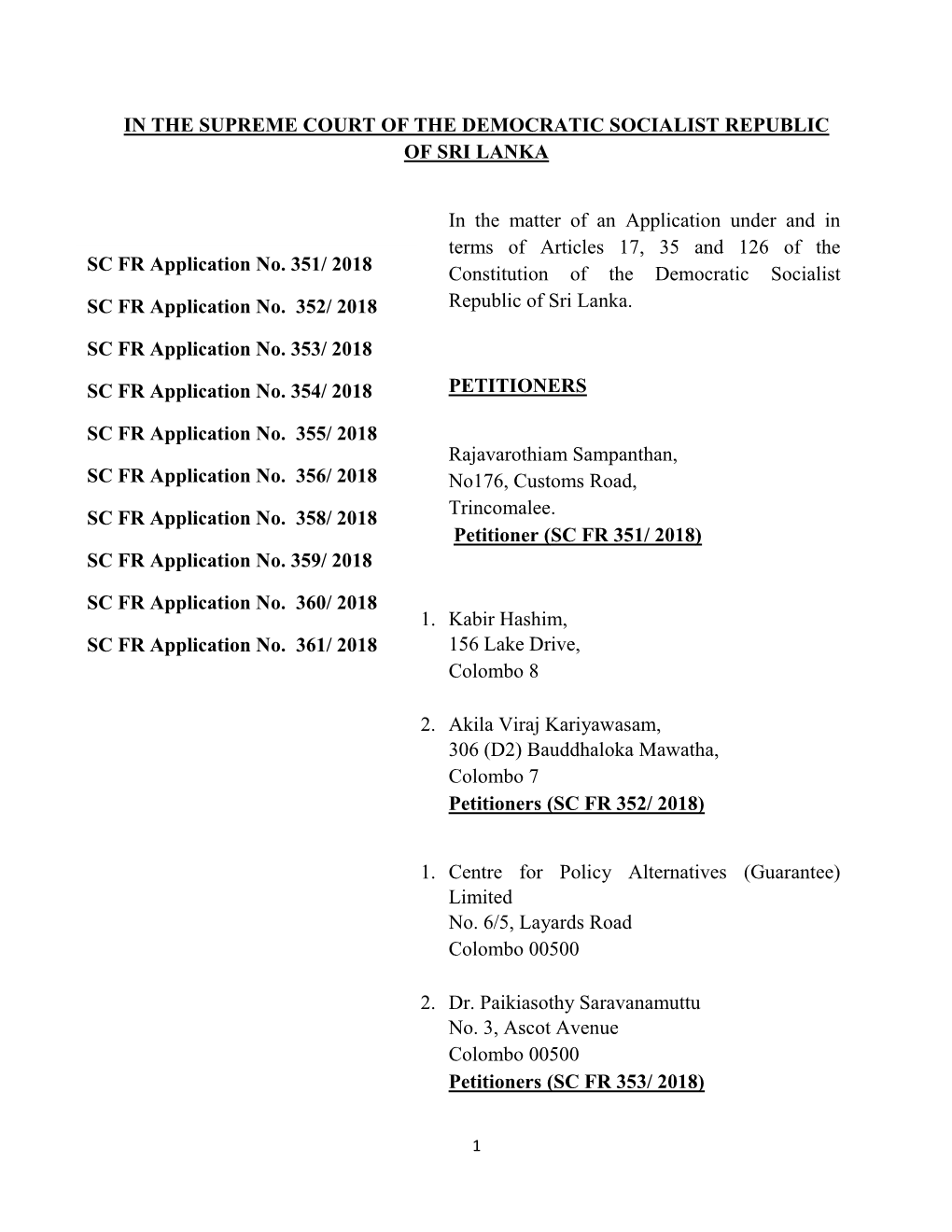

SC FR Application No. 351/ 2018 Constitution of the Democratic Socialist SC FR Application No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Ninth Parliament - First Session) No. 62.] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Thursday, March 25, 2021 at 10.00 a.m. PRESENT : Hon. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardana, Speaker Hon. Angajan Ramanathan, Deputy Chairperson of Committees Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Environment Hon. Dullas Alahapperuma, Minister of Power Hon. Mahindananda Aluthgamage, Minister of Agriculture Hon. Udaya Gammanpila, Minister of Energy Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena, Minister of Foreign and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. (Dr.) Bandula Gunawardana, Minister of Trade Hon. Janaka Bandara Thennakoon, Minister of Public Services, Provincial Councils & Local Government Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Labour Hon. Vasudeva Nanayakkara, Minister of Water Supply Hon. (Dr.) Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Plantation Hon. Johnston Fernando, Minister of Highways and Chief Government Whip Hon. Prasanna Ranatunga, Minister of Tourism Hon. C. B. Rathnayake, Minister of Wildlife & Forest Conservation Hon. Chamal Rajapaksa, Minister of Irrigation and State Minister of National Security & Disaster Management and State Minister of Home Affairs Hon. Gamini Lokuge, Minister of Transport Hon. Wimal Weerawansa, Minister of Industries Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Weerasekera, Minister of Public Security Hon. M .U. M. Ali Sabry, Minister of Justice Hon. (Dr.) (Mrs.) Seetha Arambepola, State Minister of Skills Development, Vocational Education, Research and Innovation Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna, State Minister of Co-operative Services, Marketing Development and Consumer Protection ( 2 ) M. No. 62 Hon. Ajith Nivard Cabraal, State Minister of Money & Capital Market and State Enterprise Reforms Hon. (Dr.) Nalaka Godahewa, State Minister of Urban Development, Coast Conservation, Waste Disposal and Community Cleanliness Hon. D. V. Chanaka, State Minister of Aviation and Export Zones Development Hon. Sisira Jayakody, State Minister of Indigenous Medicine Promotion, Rural and Ayurvedic Hospitals Development and Community Health Hon. -

C.A WRIT 388/2018 Sharmila Roweena J Ayawardene Gonawela

1 IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA In the matter of an application for the grant of a Writ of Quo Warranto, under and in . terms of Article 140 of the Constitution of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. Sharmila Roweena J ayawardene Gonawela, 30/2, Albert Crescent, Colombo 07. PETITIONER Case No: CAlWRIT/388/2018 Vs. 1. Hon. Rani! Wickramasinghe, No. 177, 5th Lane, Colombo 03. And also of No. 58, Sir Earnest De Silva Mawatha, Colombo 07. 2. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam, General Secretary, United National Party, Sirikotha, No. 400, Kotte Road, Sri J ayawardenapura Kotte. 3. W.B. Dhammika Dasanayake, Secretary General of Parliament, Parliament of Sri Lanka, Sri Jayawardenapura Kotte. 2 4. Bank of Ceylon, No. 01, BOC Square, Bank of Ceylon Mawatha, Colombo 01. 5. People's Bank, No. 75, Sri Chittampalam A. Gardiner Mawatha, Colombo 02. RESPONDENTS Before A.L. Shiran Gooneratne J. & K. Priyantha Fernando J. Counsel Uditha Egalahewa, PC with N.K. Ashokbharan instructed by Mr. H.C. de Silva for the Petitioner K. Kanag-Isvaran, PC with Suren Fernando and Niranjan Arulpragasam instructed by G.G. Arulpragasam for the 1st Respondent Suren Fernando with Ms. K. Wickramanayake instructed by G.G. Arulpragasam for the 2nd Respondent Vikum de Abrew, DSG with Manohara Jayasinghe, SSC for the 4th Respondent instructed by G. de Alwis, AAL M.L Sahabdeen for the 5th Respondent 3 Written Submissions: By the 1st and 2nd Respondents on 0110412019 By the 4th Respondent on 01104/2019 By the 5th Respondent on 02 /04/2019 By the Petitioner on 02/0412019 Supported on 26/02/2019 Decided on : 2110512019 A.L. -

Sri Lanka's Potemkin Peace: Democracy Under Fire

Sri Lanka’s Potemkin Peace: Democracy Under Fire Asia Report N°253 | 13 November 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Northern Province Elections and the Future of Devolution ............................................ 2 A. Implementing the Thirteenth Amendment? ............................................................. 3 B. Northern Militarisation and Pre-Election Violations ................................................ 4 C. The Challenges of Victory .......................................................................................... 6 1. Internal TNA discontent ...................................................................................... 6 2. Sinhalese fears and charges of separatism ........................................................... 8 3. The TNA’s Tamil nationalist critics ...................................................................... 9 D. The Legal and Constitutional Battleground .............................................................. 12 E. A Short- -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Eighth Parliament - First Session) No. 70. ] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Wednesday, May 18, 2016 at 1.00 p.m. PRESENT : Hon. Karu Jayasuriya, Speaker Hon. Thilanga Sumathipala, Deputy Speaker and Chairman of Committees Hon. Selvam Adaikkalanathan, Deputy Chairman of Committees Hon. Ranil Wickremesinghe, Prime Minister and Minister of National Policies and Economic Affairs Hon. Wajira Abeywardana, Minister of Home Affairs Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Amunugama, Minister of Special Assignment Hon. Gayantha Karunatileka, Minister of Parliamentary Reforms and Mass Media and the Chief Government Whip Hon. Ravi Karunanayake, Minister of Finance Hon. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam, Minister of Education Hon. Lakshman Kiriella, Minister of Higher Education and Highways and the Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. Daya Gamage, Minister of Primary Industries Hon. Dayasiri Jayasekara, Minister of Sports Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation Hon. Navin Dissanayake, Minister of Plantation Industries Hon. S. B. Dissanayake, Minister of Social Empowerment and Welfare Hon. S. B. Nawinne, Minister of Internal Affairs, Wayamba Development and Cultural Affairs Hon. Harin Fernando, Minister of Telecommunication and Digital Infrastructure Hon. A. D. Susil Premajayantha, Minister of Science, Technology and Research Hon. Sajith Premadasa, Minister of Housing and Construction Hon. R. M. Ranjith Madduma Bandara, Minister of Public Administration and Management Hon. Anura Priyadharshana Yapa, Minister of Disaster Management ( 2 ) M. No. 70 Hon. Sagala Ratnayaka, Minister of Law and Order and Southern Development Hon. Arjuna Ranatunga, Minister of Ports and Shipping Hon. Patali Champika Ranawaka, Minister of Megapolis and Western Development Hon. Chandima Weerakkody, Minister of Petroleum Resources Development Hon. Malik Samarawickrama, Minister of Development Strategies and International Trade Hon. -

YS% ,Xldfő Udkj Ysńlď

Human Rights Situation in Sri Lanka: Aug 2015 to Aug 2016 INFORM Human Rights Documentation Centre- 2016 Human Rights Situation in Sri Lanka: August 17, 2015 - August 17, 2016 © INFORM Human Rights Documentation Centre, 2016 Colombo Sri Lanka Cover page photos: Upper photo: Protestors demanding the release of political prisoners, 8th August 2016, Jaffna, Sri Lanka. © Tamil Guardian http://www.tamilguardian.com/content/tamils-demand-release-political-prisoners Below photo: People of Panama refuse to accede to a government order to vacate their traditional land. They were forcefully evicted from lands by military since 2010. Protest was held on 21st of June, 2016, Panama, Sri Lanka. © Sri Lankan Mirror http://www.srilankamirror.com/news/item/11216-panama-people-refuse-to-leave-their-land INFORM was established in 1990 to monitor and document human rights situation in Sri Lanka, especially in the context of the ethnic conflict and war, and to report on the situation through written and oral interventions at the local, national and international level. INFORM also focused on working with other communities whose rights were frequently and systematically violated. Presently, INFORM is focusing on election monitoring, freedom expression and human rights defenders. INFORM is based in Colombo Sri Lanka, and works closely with local activists, groups and networks as well as regional (Asian) and international human rights networks. 1 INFORM Human Rights Documentation Centre www.ihrdc.wordpress.com [email protected] Human Rights Situation in Sri Lanka: Aug 2015 to Aug 2016 INFORM Human Rights Documentation Centre- 2016 Contents Introduction and acknowledgements ........................................................................................... 3 List of Writers .............................................................................................................................. 4 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... -

Minutes of Parliament for 08.01.2019

(Eighth Parliament - Third Session) No. 14. ] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Tuesday, January 08, 2019 at 1.00 p.m. PRESENT : Hon. J. M. Ananda Kumarasiri, Deputy Speaker and the Chair of Committees Hon. Selvam Adaikkalanathan, Deputy Chairperson of Committees Hon. Ranil Wickremesinghe, Prime Minister and Minister of National Policies, Economic Affairs, Resettlement & Rehabilitation, Northern Province Development, Vocational Training & Skills Development and Youth Affairs Hon. (Mrs.) Thalatha Atukorale, Minister of Justice & Prison Reforms Hon. Wajira Abeywardana, Minister of Internal & Home Affairs and Provincial Councils & Local Government Hon. John Amaratunga, Minister of Tourism Development, Wildlife and Christian Religious Affairs Hon. Gayantha Karunatileka, Minister of Lands and Parliamentary Reforms and Chief Government Whip Hon. Ravi Karunanayake, Minister of Power, Energy and Business Development Hon. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam, Minister of Education Hon. Lakshman Kiriella, Minister of Public Enterprise, Kandyan Heritage and Kandy Development and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. Daya Gamage, Minister of Labour, Trade Union Relations and Social Empowerment Hon. Palany Thigambaram, Minister of Hill Country New Villages, Infrastructure & Community Development Hon. Navin Dissanayake, Minister of Plantation Industries Hon. Gamini Jayawickrama Perera, Minister of Buddhasasana & Wayamba Development Hon. Harin Fernando, Minister of Telecommunication, Foreign Employment and Sports Hon. R. M. Ranjith Madduma Bandara, Minister of Public Administration & Disaster Management Hon. Rishad Bathiudeen, Minister of Industry & Commerce, Resettlement of Protracted Displaced Persons and Co-operative Development ( 2 ) M. No. 14 Hon. Tilak Marapana, Minister of Foreign Affairs Hon. Sagala Ratnayaka, Minister of Ports & Shipping and Southern Development Hon. Arjuna Ranatunga, Minister of Transport & Civil Aviation Hon. Patali Champika Ranawaka, Minister of Megapolis & Western Development Hon. -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Eighth Parliament - First Session) No. 134. ] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Tuesday, December 06, 2016 at 9.30 a. m. PRESENT : Hon. Karu Jayasuriya, Speaker Hon. Thilanga Sumathipala, Deputy Speaker and Chairman of Committees Hon. Ranil Wickremesinghe, Prime Minister and Minister of National Policies and Economic Affairs Hon. (Mrs.) Thalatha Atukorale, Minister of Foreign Employment Hon. Wajira Abeywardana, Minister of Home Affairs Hon. John Amaratunga, Minister of Tourism Development and Christian Religious Affairs and Minister of Lands Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Development Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Amunugama, Minister of Special Assignment Hon. Gayantha Karunatileka, Minister of Parliamentary Reforms and Mass Media and Chief Government Whip Hon. Ravi Karunanayake, Minister of Finance Hon. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam, Minister of Education Hon. Lakshman Kiriella, Minister of Higher Education and Highways and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. Mano Ganesan, Minister of National Co-existence, Dialogue and Official Languages Hon. Daya Gamage, Minister of Primary Industries Hon. Dayasiri Jayasekara, Minister of Sports Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation Hon. Palany Thigambaram, Minister of Hill Country New Villages, Infrastructure and Community Development Hon. Duminda Dissanayake, Minister of Agriculture Hon. Navin Dissanayake, Minister of Plantation Industries Hon. S. B. Dissanayake, Minister of Social Empowerment and Welfare ( 2 ) M. No. 134 Hon. S. B. Nawinne, Minister of Internal Affairs, Wayamba Development and Cultural Affairs Hon. Gamini Jayawickrama Perera, Minister of Sustainable Development and Wildlife Hon. Harin Fernando, Minister of Telecommunication and Digital Infrastructure Hon. A. D. Susil Premajayantha, Minister of Science, Technology and Research Hon. Sajith Premadasa, Minister of Housing and Construction Hon. -

April - June 2016

Issue No. 151 April - June 2016 A protest on a Human Rights issue “In the last thirty or more years we have seen the failure of those holding high political office to observe and respect the spirit of the Constitution and the law. One can see many people blaming the 1978 Consti- tution for the many ills in our country, but the fault lies not in the Constitution, but in the men and women who have failed to operate the Constitution in the correct spirit” by Saliya Pieris - The Sunday Leader - 01/05/2016 Human Rights Review : April - June Institute of Human Rights 2 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Editorial 03 Signs of discontent Buddha on excessive taxes, and good governance 05 Possibility Of All MPs Getting Ministerial Posts – Dr. Nirmal Ranjith Devasiri If we don’t kill corruption, it will kill Sri Lanka 06 Like Oliver Twist, Our Political Fat-Cats Want More 07 The Menace of a clannish herd Sajin Vass: Witness Most Corrupt 08 Of Taxation, Inland Revenue And Panama Papers Yahapalanaya is not transparent - Prof.Sarath Wijesooriya 09 Citizen Power And The Opposition 11 More than mere obstacles on the road to Governance? Justice Delayed Is Corruption Condoned 13 Continuing To Protect Thieves? 14 Situation in the North & East Seven years after the end of Sri Lanka’s War 14 Media Attacks Journalist attacked within MC premises 15 UNHRC & The International Front Torture still continues: UN rapporteurs slam CID, TID 15 Armitage Does Mediator Role; Meets TNA To Discuss Issues 16 Alleged war crimes: PM announces probe will be domestic, no foreign -

Meezan Academic and Professional Journal Comprising Scholarly and Student Articles

ANMEEZAN ACADEMIC AND PROFESSIONAL JOURNAL COMPRISING SCHOLARLY AND STUDENT ARTICLES ND 52 EDITION Edited by: Afra Laffar Zaid Muzam Ali Fahama Abdul Latheef All rights reserved, The Law Students’ Muslim Majlis Sri Lanka Law College Cover Design: Harshana Jayaratne Copyrights All material in this publication is protected by copyright, subject to statutory exceptions. Any unauthorized of The Law Students’ Muslim Majlis, may invoke inter alia liability for infringement of copyright. Disclaimer All views expressed in this production are those of the respective author and do not represent the opinion of The Law Students’ Muslim Majlis or Sri Lanka Law College. Unless expressly stated, the views expressed are the author’s own and are not to be attributed to any instruction he or she may present. Submission of material for future publications The Law Students’ Muslim Majlis welcomes previously unpublished original articles or manuscripts for publication in future editions of the "Meezan". However, publication of such material would be at the discretion of the Law Students’ Muslim Majlis, in whose opinion, such material must be worthy of publication. All such submissions should be in duplicate accompanied with a copy on a compact disk and contact details of the contributor. All communication could be made via the address given below. Citation of Material contained herein Citation of this publication may be made due regard to its protection by copyright, in the following fashion: 2018, issue 52ndMeezan, LSMM. Review, Responses and Criticism The Law Students’ Muslim Majlis welcome any reviews, responses and criticism of the content published in this issue. The President The Law Students’ Muslim Majlis Sri Lanka Law College, 244, Hulftsdrop Street, Colombo 12. -

Decisions of the Supreme Court on Parliamentary Bills

DECISIONS OF THE SUPREME COURT ON PARLIAMENTARY BILLS 2014 - 2015 VOLUME XII Published by the Parliament Secretariat, Sri Jayewardenepura Kotte November - 2016 PRINTED AT THE DEPARTMENT OF GOVERNMENT PRINTING, SRI LANKA. Price : Rs. 364.00 Postage : Rs. 90.00 DECISIONS OF THE SUPREME COURT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA UNDER ARTICLES 120, 121 AND 122 OF THE CONSTITUTION OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA FOR THE YEARS 2014 AND 2015 i ii 2 - PL 10020 - 100 (2016/06) CONTENTS Title of the Bill Page No. 2014 Assistance to and Protection of Victims of Crime and Witnesses 03 2015 Appropriation (Amendment ) 13 National Authority on Tobacco and Alcohol (Amendment) 15 National Medicines Regulatory Authority 21 Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution 26 Penal Code (Amendment) 40 Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) 40 iii iv DECISIONS OF THE SUPREME COURT ON PARLIAMENTARY BILLS 2014 (2) D I G E S T Subject Determination Page No. No. ASSISTANCE TO AND PROTECTION OF VICTIMS 01/2014 to 03 - 07 OF CRIME AND WITNESSES 06/2014 to provide for the setting out of rights and entitlements of victims of crime and witnesses and the protection and promotion of such rights and entitlements; to give effect to appropriate international norms, standards and best practices relating to the protection of victims of crime and witnesses; the establishment of the national authority for the protection of victims of crime and witnesses; constitution of a board of management; the victims of crime and witnesses assistance and protection division of the Sri Lanka Police Department; payment of compensation to victims of crime; establishment of the victims of crime and witnesses assistance and protection fund and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto. -

In the Supreme Court of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA In the matter of an Application under and in terms of Articles 17 and 126 of the Constitution of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. 1. Athula Chandraguptha Thenuwara, 60/3A, 9th Lane, EthulKotte. (Petitioner in SC Application 665/12 [FR]) S.C. APPLICATION No: 665/2012(FR) 2. Janaka Adikari Palugaswewa, Perimiyankulama, S.C. APPLICATION No: 666/2012(FR) Anuradhapaura. S.C. APPLICATION No: 667/2012(FR) (Petitioner in SC Application 666/12 [FR]) S.C. APPLICATION No: 672/2012(FR) 3. Mahinda Jayasinghe, 12/2, Weera Mawatha, Subhuthipura, Battaramulla. (Petitioner in SC Application 667/12 [FR]) 4. Wijedasa Rajapakshe, Presidents’ Counsel, The President of the Bar Association of Sri Lanka. (1st Petitioner in SC Application 672/12 [FR]) 5. Sanjaya Gamage, Attorney-at-Law The Secretary of the Bar Association of Sri Lanka. (2nd Petitioner in SC Application 672/12 [FR]) 6. Rasika Dissanayake, Attorney-at-Law The Treasurer of the Bar Association of Sri Lanka. (3rd Petitioner in SC Application 672/12 [FR]) 7. Charith Galhena, Attorney-at-Law Assistant-Secretary of the Bar Association of Sri Lanka. (4th Petitioner in SC Application 672/12 [FR]) Petitioners Vs. 1 1. Chamal Rajapakse, Speaker of Parliament, Parliament of Sri Lanka, Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte. 2. Anura Priyadarshana Yapa, Eeriyagolla, Yakawita. 3. Nimal Siripala de Silva, No. 93/20, Elvitigala Mawatha, Colombo 08. 4. A. D. Susil Premajayantha, No. 123/1, Station Road, Gangodawila, Nugegoda. 5. Rajitha Senaratne, CD 85, Gregory’s Road, Colombo 07. 6. Wimal Weerawansa, No. -

Covid-19 a Refining Local Cases Total Cases 3,388 Process Deaths Recovered Active Cases 130 13 3,245 Rs

DEVELOPING AN ENERGY HUB COVID-19 A REFINING LOCAL CASES TOTAL CASES 3,388 PROCESS DEATHS RECOVERED ACTIVE CASES 130 13 3,245 RS. 70.00 PAGES 88 / SECTIONS 7 VOL. 03 – NO. 01 SUNDAY, OCTOBER 4, 2020 CASES AROUND THE WORLD RECOVERED TOTAL CASES 25,732,161 DECISIVE IMF STILL DEATHS WEEK AHEAD CONSIDERING 34,579,033 1,029,177 FOR 20A RFI REQUEST THE ABOVE STATISTICS ARE CONFIRMED UP UNTIL 8.10 P.M. ON 02 OCTOBER 2020 »SEE PAGES 8 & 9 »SEE BUSINESS PAGE 1 »SEE PAGE 4 Japan’s tit for LRT tat z Decides to hold transmission and distribution project z Concerned about SL debt situation and financial policy BY MAHEESHA MUDUGAMUWA Greater Colombo Transmission bilateral co-operation are until the above mentioned situations and Distribution Loss Reduction treated with gravity by Japan. are improved,” the letter stated. In what is likely a reaction to the Sri Lankan Government’s Project Phase II towards the The policies included the “JICA shall follow the Government stance on the Colombo Light Rail Transit (LRT) Project, the appraisal stage”. request for a debt moratorium of Japan’s policies but we are willing Japanese Government has decided to put on hold the Greater The letter, signed by JICA South by the GoSL to Japan, the to restart the formulation process Colombo Transmission and Distribution Loss Reduction Asia Department South Asia Division construction of a new power regarding the project once the Project Phase II. 3 Director Naoaki Miyata, stated that plant, and the project for Government of Japan confirms the Japan is concerned about the current establishing an LRT system situations are improved.” In a letter written to the Director was seen by The Sunday Morning, debt situation of the Government in Colombo.